Heavier traffic on Corridor 10: smuggling of migrants through North Macedonia

In 2015, more than half a million refugees and migrants came streaming through the Western Balkans, particularly from Greece, through North Macedonia, into Serbia and then Hungary. Although this so-called Balkan route was declared closed in March 2016, the flow never fully stopped; in recent months, it has again increased. Migrants are still being smuggled along Corridor 10 – the main transportation route from Thessaloniki through North Macedonia and Serbia to Budapest, as well as west from Belgrade via Croatia and Slovenia, to Graz and Salzburg in Austria.

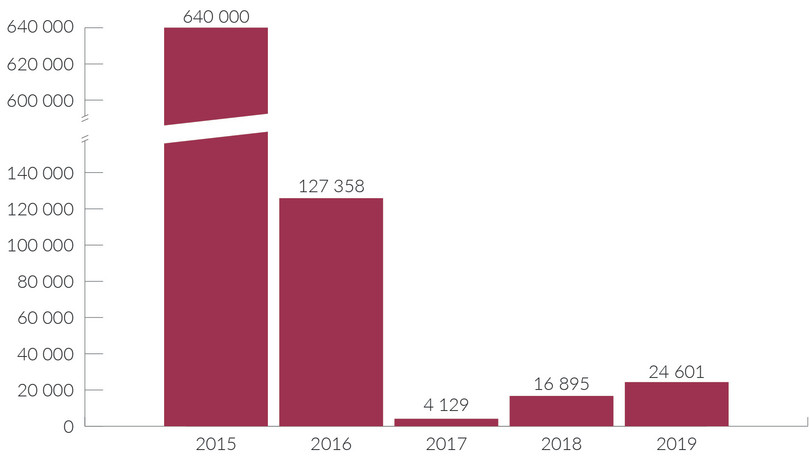

In 2015, dramatic images were broadcasted worldwide of asylum seekers and migrants trying to cross the border from Greece into North Macedonia, in an effort to head northwest along the Balkan route into central Europe. After the Balkan route was closed, the number of irregular crossings plummeted from 694 674 in 2015 to just over 4 000 in 2017.1

Since early 2016, increased border security, like the erection of fences and the deployment of Frontex border guards and joint border patrols, have caused migrants to shift to the Adriatic route that passes from Greece into Albania, through Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and then into Croatia. The closure of the Balkan route also led migrants and asylum seekers to rely more on criminal networks to provide smuggling services and fraudulent travel documents.2

However, the number of people trying to cross from Greece into North Macedonia – and from there into southern Serbia – has been growing since 2019. Corridor 10 has regained popularity as an artery for smuggling migrants: in 2019, there were almost 25 000 reported irregular crossings into North Macedonia.3 Most of the asylum seekers and migrants are young men coming from the Middle East and North Africa, as well as Afghanistan and Pakistan.4

Figure 1 Statistics on irregular crossings through North Macedonia.

Source: Ministry of Interior of the Republic of North Macedonia, Annual reports for 2017, 2018 and 2019 and Report for risk assessment on organized and serious crime (2017–2019).

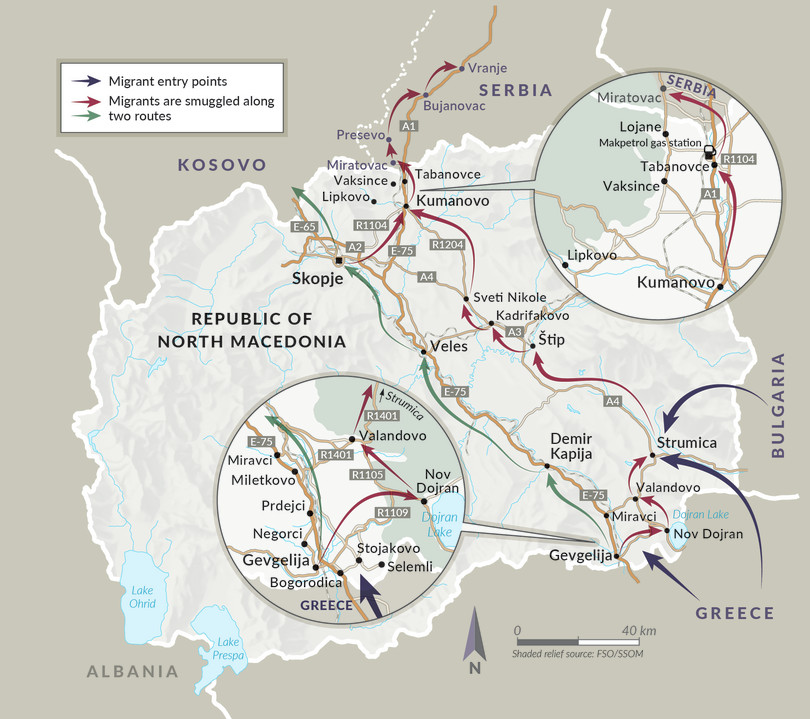

Entry points and smuggling routes

Migrants are smuggled through North Macedonia in three main steps: crossing from Greece into North Macedonia, transiting through North Macedonia, and crossing from North Macedonia into Serbia. The smuggling of migrants from Greece into North Macedonia takes place along two main routes: one from the village of Idomeni (Greece) to Gevgelija (North Macedonia), and another along unmarked paths over Belasica mountain, near the city of Strumica (North Macedonia).

In 2015, Idomeni was the main crossing point for hundreds of thousands of migrants and refugees on their way to central Europe. Today, it remains a hub, but at a significantly lower level. Migrants are picked up by smugglers in the vicinity of the Hara hotel, which is located on the Е-75 highway that connects Thessaloniki and Skopje. Most smuggling is conducted by Afghans and Pakistanis, often in cooperation with North Macedonian citizens. The most common routes pass through the border village of Moin, west of the Vardar river, and the villages of Stojakovo, Prdejci, Selemli, Negorci, Miravci, Miletkovo and Bogorodica.

Migrants are often smuggled in cars and trucks through the Bogorodica border crossing. There have also been several cases of migrants trying to cross the border by passenger or freight train at the Gevgelija railway border crossing. This can be dangerous: migrants have been injured or killed while trying to jump onto moving trains or coming into contact with high-voltage cables.5 In 2015, 14 migrants who had fallen asleep on the tracks were killed by a train travelling from Thessaloniki to Belgrade.6

The second route runs across the mountain at Belasica and through the Dojran region, where North Macedonian police regularly discover migrants.7 For example, in July 2020, police found 12 Syrian migrants near the village of Davidovo in a personal vehicle with Serbian license plates, which was driven by a Serbian citizen from Vranje.8

After having crossed into North Macedonia, migrants head north along Corridor 10 from Gevgelija through Veles to the capital, Skopje. Improvement of the highway between Demir Kapija and Smokvica has increased the speed of traffic and reduced the number of controls, thereby making it easier to smuggle migrants. An alternative route used by smugglers to avoid police patrols runs from Gevgelijato Kumanovo through Bogdanci, Valandovo, Strumica and Stip.

Figure 2 Migrant entry points and smuggling routes via North Macedonia.

To reduce their risks, smugglers often use vehicles with lost or stolen license plates and accommodate migrants in abandoned or empty houses. Smugglers often wear masks and gloves to avoid leaving any DNA traces or fingerprints in the vehicles – a practice that does not arouse much suspicion because of COVID-19 precautions.

Close to the Serbian border, migrants are usually dropped off near Kostrnik, the Makpetrol gas station on highway Е-75 or the Tabanovcering road. From there, they are picked up and brought to the villages of Lipkovo, Lojane or Vaksince in the Lipkovo region – muslim-majority villages that provide a safe haven for smugglers and migrants alike. Then, the migrants are smuggled to the village of Miratovac in Serbia, where Serbian criminal groups take over. In response, Serbia is erecting a fence along its border with North Macedonia, to stem the flow.9

In southern Serbia, many asylum seekers and migrants congregate in camps around Preševo, Bujanovac and Vranje. As of 9 November 2020, there were an estimated 900 asylum seekers and migrants in these three camps. From there, they try to head north.

Smuggling methods

The smuggling of migrants via North Macedonia is facilitated by criminal networks that have connections in the countries of origin and destination, as well as in neighbouring countries, thus ensuring continuity along the entire route. They offer a full range of services including accommodation, the provision of fraudulent documents, and information on contact points in countries farther along the route.

These criminal networks have a vertical structure with clearly defined roles for each member, such as host, spotter, transporter, facilitator and cashier. For example, the responsibility of the host is to take care of the migrants once they enter North Macedonia, while the spotter’s job is to identify police patrols, checkpoints or ambushes along the route and inform the remaining members of the network.10

To communicate in a way that avoids detection, smugglers use social-media messenger applications like WhatsApp, Viber or Telegram. They also rely on social media and use online platforms to arrange the facilitation of services.11 In addition, they track the migrants using GPS devices. Communication tools are often changed or combined; for example, it is not unusual for smugglers to initiate communication via mobile phones or over the internet and continue on work phones or radios.

The fee charged for smuggling migrants from Greece through North Macedonia and into Serbia is between €300 and €1 500, depending on the transport method, the quality of accommodation and other services. It is worth noting that this is around the same price charged in 2015 and until early 2016. Fees apparently jumped to as high as €3 500 in the period immediately after the Balkan route was closed.12 Fees are usually paid either in advance in cash in one of the big Greek cities, to the driver or to the guide, or using money transfer services like the hawala system.13

There are indications that smugglers sometimes cooperate with police officers, who give them information about police patrols and checkpoints. For example, in 2016, as a result of a sting operation codenamed Coyote, 19 people were arrested and five police officers were investigated for migrant smuggling, selling drugs, abusing their position and false identification in the regions of Veles, Negotino, Gevgelija and Skopje. The police officers were charged with providing information, logistics and even police uniforms to a criminal group.14

In another case, in 2018–2019, the North Macedonian police apprehended 17 members of an organized-crime group, including a senior police officer from Stip who had been involved in smuggling migrants. Members of the criminal group had used an accomplice in the police to receive tip-offs about anti-smuggling operations and how to cover up their criminal activities.15

But police have also had success in breaking up smuggling rings. In October 2019, police officers in North Macedonia, as part of operation Reflex, prevented the entry of 252 migrants along the borders with Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia.16 The criminal network was organized by a father and son from Bogdanci who, between December 2019 and October 2020, smuggled around 100 migrants into the country for a significant profit. The remaining group members were transporters who moved the migrants across North Macedonia. Most of the migrants were originally from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria, Iran, Egypt and other Middle Eastern countries.17

While the number of people on the move diminished significantly between March and May 2020 as a result of pandemic-related restrictions,18 the numbers started increasing again in June and have been rising ever since: during the first nine days of October, North Macedonian police apprehended 878 migrants close to the border with Greece. This increase is not only creating a bigger market for smuggling migrants, but it is also exacerbating a humanitarian crisis in southern Serbia where camps housing asylum seekers and migrants are growing.

Notes

-

Ministry of Interior of the Republic of North Macedonia, Report for risk assessment on organized and serious crime (2010–2015) and Report for risk assessment on organized and serious crime (2017–2019). ↩

-

Southeast European Law Enforcement Center, 2019 Report on illegal migration in Southeast Europe, https://www.selec.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/SELEC-Report-on-Illegal-Migration-in-SEE_public-version.pdf. ↩

-

Ministry of Interior of the Republic of North Macedonia, 2019 Annual report, https://bit.ly/3maca8s. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Sashko Panajotov, Infomigrants: Migranti odnovo se upatuvaat kon balkanskata mar ruta preku Idomeni, Mia, 22 July 2020, https://mia.mk/infomigrants-migranti-odnovo-se-upatuvaat-kon-balkanskata-ruta-preku-idomeni/. ↩

-

Akademik, Voz vo blizina na Veles pregazi 14 migranti: mashinovozacot nemal uslovi da go sopre vozot, informiraat od obvinitelstvoto, 24 April 2015, https://akademik.mk/voz-vo-blizina-na-veles-pregazi-14-migranti-mashinovozachot-nemal-uslovi-da-go-sopre-vozot-informiraat-od-obvinitelstvo-3/. ↩

-

Zoran Georgiev, Divite pateki preku Belasica-nova balkanska ruta za migrantite niz Makedonija, Sitel, 18 July 2020, https://sitel.com.mk/divite-pateki-preku-belasica-nova-balkanska-ruta-za-migrantite-niz-makedonija. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Serbian authorities have begun to erect a fence on the border with Macedonia, in the area of Presevo. This part of the border is notorious for the frequent movement of migrants, who cross Macedonia after entering through Greece, and use villages on the Macedonian side of the border as staging grounds while they wait to enter Serbia. Macedonia also has a similar fence near Gevgelija, on the border with Greece. ↩

-

Ivan Sterjoski and Bojana Bozinovska. Trafficking in human beings and smuggling of migrants in North Macedonia, Macedonian Young Lawyers Association, May 2019, https://bit.ly/399ddSc. ↩

-

Southeast European Law Enforcement Center, 2019 Report on Illegal Migration in Southeast Europe, https://www.selec.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/SELEC-Report-on-Illegal-Migration-in-SEE_public-version.pdf. ↩

-

Ministry of Interior of the Republic of North Macedonia, Report for risk assessment on organized and serious crime (2017–2019). ↩

-

Ministries of Internal Affairs of Serbia, Montenegro and Macedonia, Regional serious and organized crime threat assessment, http://www.mvr.gov.mk/Upload/Editor_Upload/analizi-statistiki/Socta%20izvestaj%202016%20ENG.pdf. ↩

-

Vladimir Kalinski, Uapseni policajci osomniceni za shverc na migrant, Radio Slobodna Evropa, 20 July, 2016, https://www.slobodnaevropa.mk/a/27869604.html. ↩

-

S. K. Delevska, Uapsen policiski nacalnik za Shtip za shverc na migrant, povekepati otkrienata ruta uste e ziva, 15 February 2019, https://sdk.mk/index.php/makedonija/uapsen-politsiski-nachalnik-na-shtip-za-shverts-na-migranti-povekepati-otkrienata-ruta-ushte-e-zhiva/. ↩

-

Republic of North Macedonia, Ministry of Interior, 16 October 2020, https://mvr.gov.mk/vest/13225. ↩

-

Mak Press, Akcija na MVR protiv organizirana grupa za kriumcarenje migrant, se koristea I helihopteri, 15 October 2020, https://vesti.mk/read/article/https%3A%2F%2Fmakpress.mk%2FHome%2FPostDetails%3FPostId%3D374320. ↩

-

Pelagija Stojancova, Balkanskata migrantska ruta povtorno atraktivna, Radio Slobodna Evropa, 26 June 2020, https://bit.ly/376YOng. ↩