Organized crime through a gender lens

‘We worked for 45 days drying, cleaning and packing the cannabis that would be sent to Italy from the shores of Kurbin. It was intensive, but a satisfactory experience. For eight hours, we were paid 2 000 Lek [€16]; if you worked for 10 hours, you could get 2 500 Lek [€19]. With the money I earned, I bought clothing and schoolbooks for my three children.’1

‘It is a pity that in one year this job lasts no more than 40 days. Me and my husband do not have any job and working more often would be profitable.’2

Two women engaged in the cultivation of cannabis in Albania, who told us their stories, provided insight into the role of women in this illicit activity. Reports of women being engaged in the cultivation of cannabis in Albania date back to the beginning of the 1990s, when they planted cannabis in their gardens.3 Since then, women are believed to have played a key role in the industry, specializing mostly in the process of cleaning cannabis.

Cases are rare, but women have also been involved in more senior positions in criminal groups in the region. On 22 September 2020, a Serbian woman heading an international cannabis-trafficking group was arrested in Spain together with 30 other members of the group (mostly from Serbia, Croatia and the UK), some of whom had previous criminal records in Serbia and were wanted by the authorities.4 In addition, 12 600 plants, 190 kilogrammes of processed buds and €50 000 in cash were seized.5 The network had more than a dozen indoor cultivation facilities close to Barcelona, equipped with rapid-cultivation technology. Their product was distributed in Catalonia. According to Spanish authorities, this was the most important criminal organization involved in cannabis trafficking that has been dismantled this year.6

There is a growing number of global studies analyzing the role of women in organized criminal groups around the world, looking both at their roles as victims and as perpetrators.7 Policymakers are also increasingly recognizing the role of gender in shaping individuals’ vulnerabilities to organized crime. In the Western Balkans, however, the link between gender and organized crime remains understudied. Few reports on the region pay attention to the role of women in organized crime, and even fewer look at gender perceptions related to organized crime and if gender influences why and how people get involved.8

Socio-economic factors certainly play a role in terms of increasing vulnerability to organized crime. For example, 49 individuals (men and women) interviewed for a recent study unanimously identified economic hardship as the motive for their participation in illicit cannabis cultivation.9 But although socio-economic impacts are widely recognized, there is less focus on how they can affect women differently, and what this means about how men and women’s vulnerability to organized crime is shaped.

An Albanian woman with seized marijuana plants following police raids in Lazarat, Albania, June 2014.

© Gent Shkullaku/AFP via Getty Images

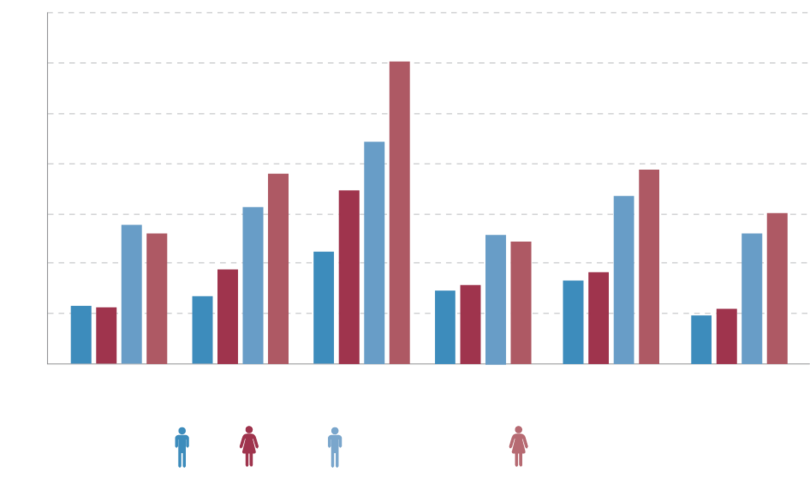

A number of leading indicators show that women face even greater economic hardship than men in the Western Balkans. For example, as shown in Figure 3, unemployment in the region is high – particularly for young women.

In 2019, there was also a gender pay gap averaging 10% in Albania, 13.9% in Montenegro and about 12% in North Macedonia. In the same year, in Serbia, the average monthly salary for a woman was €30 lower than that for a man.10

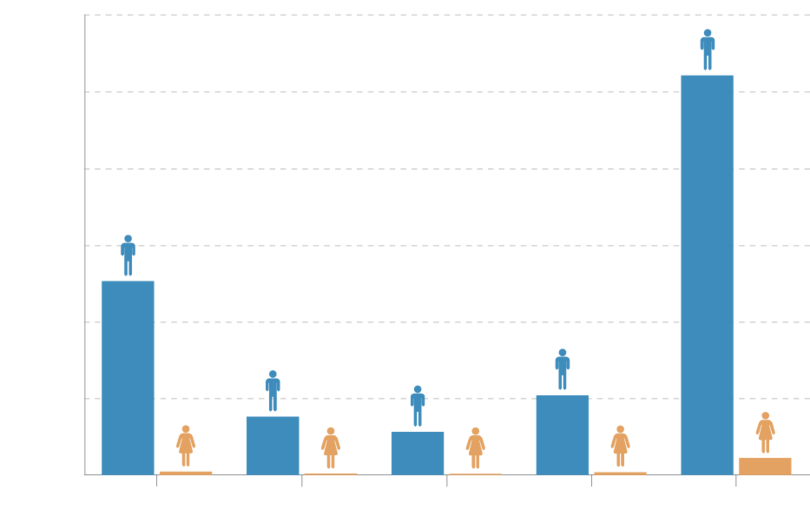

If economic hardship were a significant factor pushing people into organized crime as an income source, prisons in the Western Balkans would presumably be full of women. However, this is not the case. As seen in Figure 4, which gives an overview of the prison population in the Western Balkans Six countries in 2019, the number of women behind bars is a very small percentage of the total. At the end of 2019, 4.1% or less of the total prison population across the Western Balkans were women.11 In addition, many of these convictions are linked to petty crime (fraud and robbery), and not organized criminal activities. Since 2015, the number of women convicted for drug-related crimes in Albania has risen, including convictions from drug abuse and organized-crime-related activities.12

Official statistics also indicate that women’s role in organized crime is limited: Serbian Ministry of Interior data in 2019 shows that almost 95% of members of organized criminal groups in Serbia were men.13

Although this suggests that organized crime in the Western Balkans is a man’s world, it is key to recognize that gender perceptions shape not only the role played by individuals in organized crime, but also law-enforcement responses and interdiction patterns. Prison populations and official statistics may yield a distorted reflection of the Western Balkans’ criminal landscape.

Figure 3 Unemployment data for the Western Balkans Six, 2019.

Source: The World Bank, World Bank open data, https://data.worldbank.org/

Number of prisoners (male and female) in the Western Balkans

Figure 4 Prison populations in the Western Balkans, 2019.

Source: M Aebi and M Tiago, Prison populations, SPACE I - 2019, Council of Europe, https://wp.unil.ch/space/files/2020/04/200405_FinalReport_SPACE_I_2019.pdf; Kosovo Correctional Services, Statistics, https://shkk.rks-gov.net

Young Albanian gang members flaunt material symbols of their status.

Source: Social media

It is, however, clear that in the Western Balkans crime and masculinity are closely linked. Joining a criminal group can be attractive for some young men to feel empowered, and achieve status and wealth that are otherwise out of reach to them in their community. The image of crime, as it is distributed and shared on social media and popular culture, often portrays the gang member as being a tough, independent and powerful young man who became successful in his community or abroad, who is respected or feared among the local community and is a possible role model for young people to follow.14

Women, on the other hand, are traditionally regarded in the region as being the caretakers of the family. This concept thereby envisages women playing a limited role by assisting their men or engaging in organized crime through their involvement in non-violent or supporting tasks. These behind-the-scenes roles are less commonly the focus of law-enforcement efforts. In fact, the roles that women tend to play in organized-crime networks, together with gendered perceptions of criminality among law enforcement, may mean that women are under-represented in statistics on organized crime.

The limited focus on the role that gender plays in organized crime and the paucity of gender-sensitive data available in the Western Balkans make it difficult to accurately assess women’s roles and involvement in criminal groups. But looking at organized crime through a gender lens not only helps to better understand the informal rules and rites that shape the gender-delineated roles for men and women, but also can contribute to designing appropriate countermeasures that can change attitudes, images and behaviours, and strengthen community resilience.

Notes

-

Interview with a woman from Zheje engaged in cannabis cultivation, March 2020. ↩

-

Interview with a woman from Poro engaged in the cultivation of cannabis, 18 January 2020. ↩

-

An interview with a woman from Bolene, who is a former cannabis cultivator, February 2020. ↩

-

ATV, Srpkinja na čelu narko-bande: Hapšenje u Španiji, pokrenuta policijska akcija, 8 September 2020, ATV, https://www.atvbl.com/vijesti/svijet/srpkinja-na-celu-narko-bande-hapsenje-u-spaniji-pokrenuta-policijska-akcija-28-9. ↩

-

Mondo, OPASNE SRPKINJE: Nekoliko žena iz Srbije bile na čelu narko-mafije! Za jednom su posebno tragali!, 5 October 2020, https://mondo.me/Info/EX-YU/amp/a876698/Srpkinje-na-celu-narko-bandi-sverc-droga.html. ↩

-

Enrique Figueredo, Cae una banda de traficantes de marihuana dirigida desde Valls por una serbia que acababa de tener un bebé, 22 September 2020, La Vanguardia, https://www.lavanguardia.com/sucesos/20200922/483625919108/barcelona-tarragona-marihuana-guardia-civil-valls-mujer-serbia.html. ↩

-

Europol, Crime has no gender: meet Europe’s most wanted female fugitives, Europol, 18 October 2019, https://www.europol.europa.eu/newsroom/news/crime-has-no-gender-meet-europe%E2%80%99s-most-wanted-female-fugitives. ↩

-

This article recognizes gender as non-binary and understands that members of the LGBTQI community will also experience and react differently to organized crime. ↩

-

Fatjona Mejdini, Cannabis cultivation in Albania. An assessment, 2020 (unpublished). ↩

-

Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, Average salaries and wages, by regions, qualification levels and sex, https://data.stat.gov.rs/Home/Result/2403040509?languageCode=en-US; Center of Investigative Journalism in Montenegro, NEJEDNAKE PLATE ŽENAMA U ODNOSU NA MUŠKARCE: Diskriminacija i po novčaniku, 1 March 2020, http://www.cin-cg.me/nejednake-plate-zenama-u-odnosu-na-muskarce-diskriminacija-i-po-novcaniku/; Radio MOF, Родов јаз во плати во Македонија, 10 April 2018, https://www.radiomof.mk/infografik-rodov-jaz-vo-plati-vo-makedonija/; INSTAT, Women and men in Albania 2020, 2020, http://www.instat.gov.al/en/themes/demography-and-social-indicators/gender-equality/publication/2020/women-and-men-in-albanian-2020/. ↩

-

Percentage of female prisoners: 1.7% (86) of all prisoners in Albania were female; 2.2% (35) in Kosovo; 2.6% (30) in Montenegro; 3.3% (70) in North Macedonia and 4.1% (441) in Serbia. No concrete data was available for Bosnia and Herzegovina, where it is estimated that women make up 3–10% of the total prison population. See M Aebi and M Tiago, SPACE I – 2019, Council of Europe annual penal statistics: prison populations, https://wp.unil.ch/space/files/2020/04/200405_FinalReport_SPACE_I_2019.pdf; Kosovo Correctional Services, Statistics, https://shkk.rks-gov.net; Ženski zatvori u BiH imaju problema s kapacitetom, Zenit, 11 November 2019, https://www.zenit.ba/zenski-zatvori-u-bih-imaju-problema-s-kapacitetom/. ↩

-

INSTAT, Perpetrators by criminal offences and sex, General Directorate of Prisons, http://instat.gov.al/en/themes/demography-and-social-indicators/crimes-and-criminal-justice/#tab2. ↩

-

Data presented at a meeting between the Working Group of the National Convention on the EU Chapter 24 and the Negotiating Group of the Government of Serbia on Justice, Freedom and Security, Belgrade, 18 February 2020. ↩

-

Mladi kriminalci u Srbiji su zvezde Instagrama, a evo ko je najviše kriv za to, Telegraf, 24 July 2019, https://www.telegraf.rs/amp/zivot-i-stil/porodica-zivot-i-stil/3085559-mladi-kriminalci-u-srbiji-su-zvezde-instagrama-a-roditelji-su-i-te-kako-krivi-sto-ih-deca-obozavaju?fbclid=IwAR2IZWnzJdCE6BhZh3-_SNUpeA1wxWsuh79JEmFwBB2rhYyR6QReMmiVTzg. See also Marcello Ravveduto, La paranza dei bambini, La Google Generation di Gomorra, Questione Giustizia, 14 January 2017, https://www.questionegiustizia.it/articolo/la-paranza-dei-bambini-la-google-generation-di-gomorra_14-01-2017.php. ↩