Phishing in North Macedonia

In 2016, North Macedonia gained notoriety when it was discovered that pro-Trump and anti-Clinton websites originating in the small town of Veles were disseminating fake news from dozens of other websites during the US presidential election.1 Since then, the problem seems to have reversed, as North Macedonian institutions and businesses have become the victims of cyber attacks.2

Digitalization has opened up new opportunities, but also brought major risks. As more and more people shop, bank and communicate online, criminals are taking advantage of transactions in cyberspace to steal money and identities.3 One of the most widely used types of internet fraud is commonly known as ‘phishing’.

Phishing is a social-engineering technique used to steal data or commit fraud. It is done by sending fake ads via bogus websites to unsuspecting users. The ads typically contain sales promotions for various goods, including, for example, gadgets or vehicles at temptingly low prices. This is done to lure potential victims into sharing sensitive information, such as personal data, usernames and passwords, as well as payment-card and bank details. Recent cases in North Macedonia demonstrate how these criminals operate and their impact on small and medium-sized businesses.

As the example below shows, the URL address in the screenshot is fake: instead of ‘facebook’ in the URL, it reads ‘fakebook’. When the user clicks on the link, his or her computer becomes infected with malicious software, which allows it to be controlled by a hacker.

In North Macedonia, a recent spate of cybercrime cases highlights vulnerabilities. Small- and medium-sized enterprises are increasingly moving online to attract more customers and to carry out business-to-business transactions. This trend has accelerated during the COVID-19 crisis. However, many of these businesses do not have special IT or security departments that can reduce their cyber security risks, nor do they sufficiently warn or train their staff about these threats.

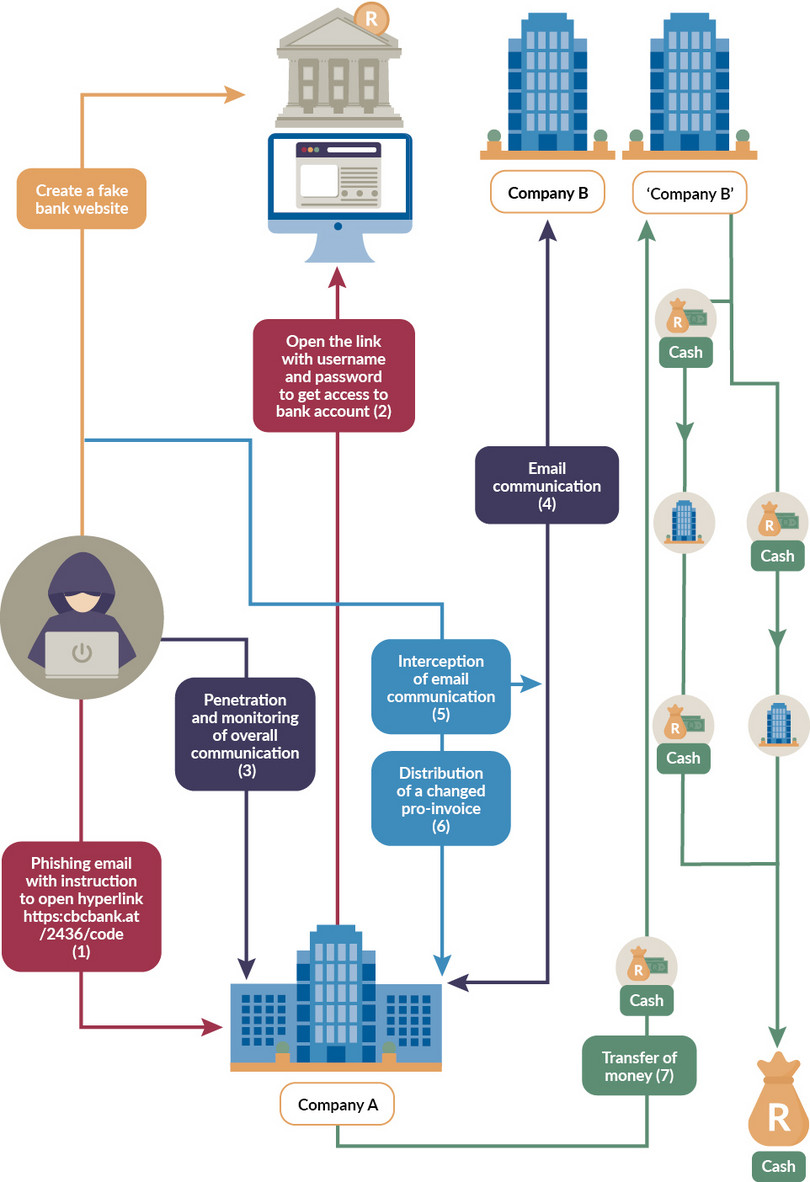

North Macedonia’s National Centre for Computer Incidents Response reports that during 2020 – particularly since the outbreak of the pandemic – they have detected a growing trend of phishing campaigns targeting users, including businesses.4 Internet fraud in North Macedonia is mainly related to the illegal interception of business communication through emails between companies in the country and their business partners abroad.5 The perpetrators pretend to represent a foreign company and provide a bank account for the payment. In this way, a legitimate payment from the company in North Macedonia to a foreign business partner is diverted to an account that is controlled by the criminals. These criminals are often hard to detect, as they frequently change the servers used for intercepting emails and the bank accounts into which the money is paid.6

Screenshot of a phishing ad, North Macedonia

Figure 5 Typical stages in a phishing attack and interception of email communication.

According to the North Macedonian police, this type of fraud has caused hundreds of thousands of euros worth of damage to the local economy.7

Two cases from the town of Gostivar illustrate the problem. In the first, a hacker managed to penetrate the software system of a company in Gostivar by intercepting email communication between the company and its business partners. In March 2016, a man from the Czech Republic introduced himself to the company in Gostivar as the owner of a company in Switzerland. He emailed the owner of the company in Gostivar, making several online business offers. The companies exchanged electronic invoices and communicated by email regarding the payment. The North Macedonian company then received an email that appeared to be from the Swiss company, but which was actually sent by a fake company. The email requested payment of the first instalment of one of the orders and provided banking details. The North Macedonian company was thus tricked into transferring €3 600 to the wrong bank account.8

In the second case, in 2017 a well-known import–export company narrowly avoided becoming a victim of a phishing scam when it discovered at the last minute that the emailed bank details for a €10 000 payment were different from the account previously used by their business partner.9

A cyber attack can not only prove costly to a business, but may also damage its reputation. The owner of a well-known company in Skopje lost €100 000 when a hacker managed to intercept email communication between his company and a business partner in Serbia.10 The owner prefers not to publicize the story because clients and potential customers might avoid doing business with a company that is considered to be careless with its internal controls or has weak security. Companies can also be sued by customers whose data has been stolen through hacker attacks.

Large companies are not immune to cybercrime. In February 2020, the country’s biggest mobile operator, Macedonian Telecom, reported a hacker attack aimed at mobile phone users in the T-Mobile network. The users were selected through a data breach and the subsequent attacks were carried out mainly by cyber thieves in Estonia, Lithuania and Nigeria.11

The hackers’ methods are becoming increasingly sophisticated. In one case, they introduced themselves as ‘Police forces of the Republic of Macedonia’ using a fake email account (kontakts@moi.gov.mk) to send emails to physical and legal entities under the subject, ‘you have been invited to a current investigation into a bank fraud’.12 The email said: ‘We are writing to inform you that you have been invited to the Police of the Republic of Macedonia regarding a current investigation into a bank fraud. Invitation details are included in the attached PDF document.’ The hackers were so convincing because they included logos and text that looked like those used by official representatives of the Ministry of Interior, as well as an attachment that they claimed was a PDF. This attachment linked to a malicious file (mvr-31720.iso) through a URL address (https://nyschool.edu.sg/mvr-3170.iso). The malware (MSIL/Kryptik.DJ) was detected during the investigation. It is not known how many companies have been infected with this type of malicious software, so the extent of the damage cannot yet be assessed.

Although cybercrime is increasing throughout the Western Balkans, North Macedonia seems to be disproportionately affected. The country has been cited in past reports of the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center.13 Indeed, the number of complaints per capita puts North Macedonia in second place in terms of cybercrime, just behind the US. North Macedonia is ranked first in terms of the number of cybercrime offences in relation to the estimated number of internet users.14

Incidents of cybercrime are on the rise in the Western Balkans, not least because of the region’s increasing digitalization and the growing trend for online retail during the COVID-19 crisis. Customers and businesses alike need to be more savvy, while law enforcement and the private sector should look to step up their cooperation. The situation in North Macedonia needs special attention to deal with an outsized problem.

Notes

-

Samanth Subramanian, Inside the Macedonian fake-news complex, Wired, 15 February 2017, https://www.wired.com/2017/02/veles-macedonia-fake-news/. ↩

-

Bojan Stojkovski, Hackers expose gaping holes in North Macedonia’s IT Systems, BIRN, 22 May 2020, https://balkaninsight.com/2020/05/22/hackers-expose-gaping-holes-in-north-macedonias-it-systems/. ↩

-

PwC, Fighting fraud: A never-ending battle, PwC’s Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey, 2020, https://www.pwc.com/fraudsurvey. ↩

-

MKD-CIRT (Agency of Electronic Communication), Почетна страна, https://mkd-cirt.mk/. ↩

-

Kanal 5 TB, Бесими: Ќе воведеме систем на паметни финансии, 6 September 2020, https://kanal5.com.mk/besimi-kje-vovedeme-sistem-na-pametni-finansii/a437721. ↩

-

Ministry of Interior of the Republic of North Macedonia, Report for risk assessment on organized and serious crime (2017–2019), 2019, p. 29. ↩

-

Svetlana Nikoloska and Marija Gjoseva, Criminal law, Criminological and Criminalist aspects of computer fraud in the Republic of North Macedonia, The Great Powers Influence on the Security of Small States, Ohrid, 2019, pp 124–137, https://fb.uklo.edu.mk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2019-tom-2.pdf. ↩

-

See https://gostivarpress.mk/gostivarski-kompanii-vo-kandhi-na-internet-izmamnitsi/. ↩

-

Interview with a business owner who was the victim of a hacker attack, 18 September 2020. ↩

-

Alfa, Паника кај корисниците мобилните мрежи – македонски броеви мета на хакерски напад, February 2020, https://alfa.mk/panika-kaj-korisnicite-mobilnite-mrezi-makedonski-broevi-meta-na-hakerski-napad/. ↩

-

See https://mkd-cirt.mk/2020/07/31/fishing-kampanja-koja-targetira-makedonski-adresi-za-e-poshta-so-lazhno-pretstavuvanje-na-isprakjachot-kako-policija-na-republika-makedonija-kontakts-moi-gov-mk/. ↩

-

The Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), 2013 Internet Crime Report, https://pdf.ic3.gov/2013_IC3Report.pdf. ↩

-

Dragi Rashkovski, Vasko Naumovski and Goce Naumovski, Cybercrime tendencies and legislation in the Republic of Macedonia, European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 22, 127–151, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-015-9277-7. ↩