JNIM’s blockade in south-west Mali illustrates the strategic importance of controlling key licit and illicit supply routes for operational, financial and political gain.

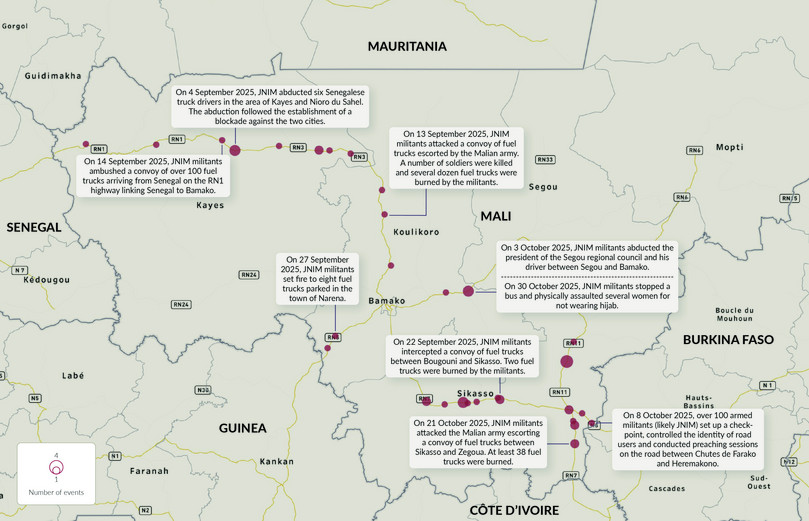

On 14 September 2025, Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) militants ambushed a convoy of more than 100 fuel trucks arriving from Senegal on the RN1 highway linking Senegal to Bamako.1 Just over a week later, JNIM attacked several fuel tankers travelling towards Bamako from Côte d’Ivoire, looting and then torching them.2 These operations — and a number of other attacks and activity by the al-Qaeda linked violent extremist organization in southern and south-western Mali — took place against the backdrop of a blockade, announced by JNIM on 1 September, of the city of Kayes and the town of Nioro du Sahel in the country’s south-west. In addition to banning residents from leaving, JNIM announced a ban on imports of fuel from neighbouring coastal states — Senegal, Mauritania, Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire.

By targeting the primary commercial arteries into Bamako, JNIM sought to asphyxiate the Malian capital to put maximum pressure on — and ultimately topple — the military junta. The economic, political and social impact did not take long to manifest. Fuel shortages quickly hit the southern regions, including Bamako, and local populations were forced to spend hours searching for petrol or were stuck at home, unable to afford sharply increased taxi fares.3 In the last week of October, Malian authorities announced the temporary nationwide closure of schools and universities as a result of the blockade-induced fuel shortage.4 Shortly afterwards, the US and many other states urged their citizens in Mali to leave the country immediately.5

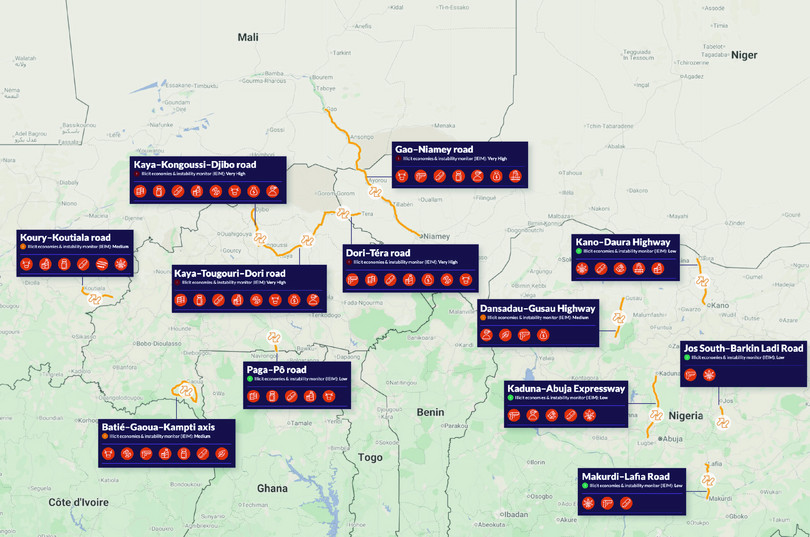

The deliberate targeting of major roads has demonstrated the strategic importance of transport infrastructure. Armed groups exploit roads for political gain by simultaneously disrupting local economies and weakening the state, positioning themselves as alternative governance providers. However, roads and transport connectivity more broadly do not only underpin the flow of licit goods sustaining national and regional economies, they also underpin the flow of illicit goods. The findings of the 2025 illicit hub mapping in West Africa highlight the intersection between roads, illicit economies and armed group violence: twelve stretches of major roads in the region were identified as illicit hubs. They are concentrated in the Sahel and Nigeria, and include cross-border arteries such as the Dori–Téra road connecting Burkina Faso and Niger.6 The findings illustrate how roads are exploited by armed groups and criminal networks for operational and financial gain through the trafficking of supplies, and through roadblocks and taxation.

Control the roads, control the population

When it comes to their engagement with illicit economies, armed groups face a trade-off between seeking support from local populations and acquiring money and other resources.7 Often, public support for them can be damaged if they engage in certain illicit economies that directly harm communities. In contrast to locations such as gold mines or national parks, where armed groups may need to build legitimacy among residents, transient populations on roads can be treated differently. Armed groups may be more predatory, extorting travellers at roadblocks or engaging in robbery, kidnapping and extortion.8

However, while armed groups often prioritize financial gain over civilian acceptance on roads, control of roads has significant implications for governance. Extortion on roads goes beyond revenue generation: it is a sign of who controls a road and, by extension, who has the authority to tax it. Safety on roads is central in shaping civilians’ livelihoods, perceptions of their own security, and their understanding of which entity is in control. They are therefore key spaces of contestation between non-state armed groups and states, all vying for influence.9

In Nigeria, for example, a bandit group reported that a number of roadblocks on the Magami–Dansadau and Kaduna–Abuja roads, while helpful in generating revenue, were also an expression of defiance towards state forces — a political step, rather than a merely criminal one.10 Violent extremist organizations in the Sahel, notably JNIM, have imposed similarly political blockades on towns and villages in Mali and Burkina Faso. At least 40 towns were under blockade in Burkina Faso by the end of 2025.11

The fuel blockade, and other violent JNIM activity in southern and south-western Mali since July 2025, illustrates how road infrastructure and illicit economies intersect to generate supplies, revenue and leverage for armed groups. The breakdown of formal supply chains is driving businesses to rely on informal networks, which are frequently taxed by JNIM, reinforcing the group’s financial control.12 More importantly, by seizing control of roads connecting Mali to other countries — primarily Côte d’Ivoire through Sikasso and Senegal through Kayes — JNIM has demonstrated its strength to the state and to local populations. Fuel is critical for the functioning of the country, and by disrupting the economy JNIM has exposed the weakness of the junta, which it is strategically pushing to its breaking point.

Figure 1 Key JNIM attacks on major roads in southern and south-western Mali, July to October 2025.

Source: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data

Armed group exploitation: operational resources and revenue extraction

Roads are pivotal for the transport of resources that are fundamental for armed groups’ ability to operate, and are an enabler of illicit economies financing the groups. Eleven of the 12 roads identified as illicit hubs in the GI-TOC’s mapping feature at least one of the five illicit economies categorized as ‘accelerant markets’: those particularly strongly linked to violence and instability. These include extortion and kidnapping but also cattle rustling and arms trafficking.

Figure 2 Road segment illicit hubs in West Africa.

Source: Lyes Tagziria and Lucia Bird, Illicit economies and instability: Illicit hub mapping in West Africa 2025, GI-TOC, October 2025.

Nearly half (47%) of illicit hubs identified across the region channel flows to conflict actors, albeit to varying degrees. Most of these hubs (81%) are concentrated in the Sahel and Central Africa, with additional clusters in Gulf of Guinea states — Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo and Benin. In hubs where illicit economies significantly contribute to conflict actor resourcing, the most prevalent commodities include excisable goods (such as motorbikes), present in 68% of such hubs; synthetic drugs (particularly tramadol) present in 60% of those hubs; fuel (59%); and medical products (48%). In other words, they reflect the flows of critical resources that enable armed groups to maintain mobility and operational capacity. The corridor between Malanville in north-eastern Benin and Gaya in southern Niger, and the major road connecting Lomé to the town of Cinkassé in northern Togo, for example, are key to the supply of fuel and motorbikes to Sahelian violent extremist groups.

Other criminal markets are equally important from a financial perspective. An illicit economy that plays an important role as a means of armed group financing, particularly for JNIM, is cattle rustling. The illicit hub mapping finds that the illicit cattle trade is far more prevalent in hubs with stronger links to conflict and violence.13 The Batié–Gaoua–Kampti axis is a key transit point for the movement of cattle stolen by JNIM in southern Burkina Faso to markets in northern Ghana and northern Côte d’Ivoire.14

Geography of illicit economies — the roads to riches

Armed groups are not the only ones that exploit roads. The geography of illicit economies across the region is closely tied to road infrastructure. Nearly nine in 10 illicit hubs (87%) lie within reach of major operational roads (59% on primary and 29% on secondary).15 From coastal ports to inland towns and villages, roads connect extraction zones and consumer markets. Capital cities in the Sahel, in particular, depend on overland transport. Landlocked Burkina Faso, for example, relies heavily on products imported from coastal countries such as Benin, Togo, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. The price difference between goods in Burkina Faso and its coastal neighbours, combined with the country’s location between coastal countries and other landlocked countries (Mali and Niger), creates the conditions for thriving contraband economies.16

Conversely, roads are vital gateways for the transportation of natural resources extracted in the Sahelian countries towards coastal states. Gold extracted in Burkina Faso, for example, is smuggled southwards by road towards the Togolese capital city, Lomé, for export by air. In December 2024, Burkinabé customs officials seized 28.6 kilograms of gold, worth more than €2 million at the time, from three passengers travelling by bus to Lomé.17

Nigeria has the largest road network in West Africa, and although most of its 195 000 kilometres are unpaved, the 60 000 paved kilometres are indispensable to the economy and the population, with about 95% of Nigerians relying on road transport for their movement and that of goods.18 However, as the main artery linking northern and southern Nigeria, the Kaduna–Abuja expressway, for example, also plays a key role in trafficking of drugs,19 primarily cannabis and tramadol sourced from states in the south to be distributed by gangs in the north.20 Similarly, the Kano–Daura highway, the primary road connecting Kano — the commercial hub of northern Nigeria — to the Nigerien border, has seen an increase in the number of people being smuggled into Niger for onward travel to North Africa and eventually Europe.21

Figure 3 National road networks in West Africa.

Source: CIA World Factbook; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development/Sahel and West Africa Club, Roads and Conflicts in North and West Africa.

Roads are critical spaces where there is overt interplay between illicit economies and violence. Most violent killings in West Africa happen within 1 kilometre of a road, and civilians are particularly vulnerable to violence at the hands of armed groups, in the form of ambushes, blockades, kidnapping and more.22 Most (75%) road segment illicit hubs in West Africa bisect regions with high rates of violent killings, and the illicit economies on roads in the Sahel are significant drivers of instability.

Reclaiming roads, therefore, is not only a matter of security; it is about restoring legitimate movement of goods, people and revenue. Roads are the physical expression of the social contract: they link communities, markets and states. As a village chief in the Kayes region put it, ‘we cannot live without these roads. The terrorists know this better than we do.’23 As long as they remain spaces of coercion, illicit profit and violence, stability in the region will remain elusive. Building fair, predictable and secure systems of mobility may be the most effective way to dismantle the infrastructure of crime.

Notes

-

David Baché, Mali: Les jihadistes détruisent des dizaines de camions-citernes et réaffirment leur blocus à Kayes, Radio France Internationale, 15 September 2025; Abdou Aziz Diedhiou, Assimi Goita: ‘Les récentes attaques des groupes armés terroristes traduisent leur désarroi’, BBC News Afrique, 22 September 2025. ↩

-

Wamaps News, Post on JNIM operations in Mali, X, 23 September 2025. ↩

-

France24, Mali: entre blocus et prises d’otages de ressortissants émiratis, YouTube, 30 September 2025; Rachel Chason, Islamist extremists have taken this country to the brink, The Washington Post, 21 October 2025. ↩

-

Samuel Benshimon, Mali: Fermeture des écoles en raison de la pénurie de carburant liée au blocus jihadiste, Sahel Intelligence, 27 October 2025. ↩

-

Travel and Tour World, Rising terrorism and travel warnings in Mali: How al-Qaeda’s presence in Bamako, Kayes, and Nioro affects tourists, 1 November 2025. ↩

-

Lyes Tagziria and Lucia Bird, Illicit economies and instability: Illicit hub mapping in West Africa 2025, GI-TOC, October 2025. ↩

-

Lucia Bird, Ladd Serwat and Eleanor Beevor, How do illicit economies build and degrade armed group legitimacy?, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data (ACLED) and GI-TOC, December 2024. ↩

-

The proliferation of roadblocks for security purposes in the Chadian capital, N’Djamena, has led to an increase in official customs staff and informal authorities known as bogo-bogo, who insist on bribes, significantly increasing transport costs for traders. See Antônio Sampaio, Conflict economies and urban systems in the Lake Chad region, GI-TOC, November 2022. Similarly, citizens of the Central African Republic have complained of extortion by state agents on the Nola–Berbérati and Salo–Nola axes. See Centrafrique: Des agents de l’etat accusés de racket sur l’axe Salo-Nola, Radio Ndeke Luka, 23 April 2024. ↩

-

GI-TOC community engagements in north-east Côte d’Ivoire (September 2022), Natitingou, Benin (October 2023) and northern Nigeria (July 2023). ↩

-

Kingsley L Madueke et al, Armed bandits in Nigeria, ACLED and GI-TOC, July 2024. ↩

-

ACAPS, Burkina Faso: Humanitarian needs in blockaded areas, thematic report, 28 May 2025. ↩

-

Timbuktu Institute, JNIM in Kayes: Economic fragility and cross-border threats, September 2025. ↩

-

Lyes Tagziria and Lucia Bird, Illicit economies and instability: Illicit hub mapping in West Africa 2025, GI-TOC, October 2025. ↩

-

Flore Berger, Cattle rustling and insecurity: Dynamics in the tri-border area between Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, GI-TOC, July 2025. ↩

-

As per the Illicit Economies and Instability Monitor expert-assessed indicator, ‘Is the location situated on/near an operational major road? [0 = no, 0.5 = secondary road, 1 = major road]’. Regional variations are notable: in the Sahel (56%), coastal states (74%) and Nigeria (64%), most hubs cluster along primary roads, whereas in Central Africa most are tied to secondary routes (56%), with 27% near primary roads and 17% disconnected. These include mostly gold sites in northern Chad as well hubs in Cameroon’s North and Southwest regions. To some extent this reflects the overall lower road density of Central Africa and the Sahel compared to coastal West Africa. The findings differ only marginally from 2022, when 73% of hubs were on or near primary roads, and 18% on or near secondary roads. Only 10% of illicit hubs were not on or near major operational roads in 2022. The increased share of poorly connected hubs in the 2025 iteration reflects in part the identification of several new illicit hubs that are either forests/national parks or gold sites (of which there are an additional 12 and four, respectively). ↩

-

Lyes Tagziria and Lucia Bird, Illicit economies and instability: Illicit hub mapping in West Africa 2025, Ouagadougou illicit hub, GI-TOC, October 2025. ↩

-

Mensah Agbenou, Burkina Faso: Saisie de 28,6 kg d’or à destination de Lomé, IciLome, 19 December 2024. ↩

-

Damilola Aina, 95% of Nigerians rely on road transport — FG, Punch, 3 November 2025. ↩

-

Interview with senior Kaduna government official, Kaduna, July 2024. ↩

-

News Agency of Nigeria, NDLEA intercepts China, UK-bound cocaine, amphetamine consignments, Pulse, 19 May 2024. ↩

-

Interviews with civil society organizations, Kano, August 2024. ↩

-

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development/Sahel and West Africa Club, Roads and Conflicts in North and West Africa, 14 February 2025. ↩

-

Fatoumata Maguiraga, Attaques terroristes en hausse: Le Mali étranglé sur ses routes, Journal du Mali, 11 July 2025. ↩