The number of civilian casualties is growing in West Africa as conflict areas increasingly overlap with illicit economies.

On 5 September 2022, a convoy of vehicles struck an improvised explosive device (IED) in Burkina Faso. At least 35 civilians were killed and several dozen more injured. The vehicles were travelling southbound on the road between Bourzanga and Djibo, in the country’s Sahel region, headed to the capital city, Ouagadougou.1 While no group has claimed responsibility for the attack, it was almost certainly the work of violent extremists affiliated with al-Qaeda, the Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), who have been operating in the country since the beginning of the insurgency in 2015.2 According to an internal security report for aid workers, this is the fifth explosion to have taken place in the province of Soum since the beginning of August.3 This latest IED attack was quickly followed by a suspected jihadist massacre of nine people, the vast majority of whom were civilians, in the village of Tassiri in the Sahel region, close to the border with Niger.4

Such incidents are evidence of the growing number of civilian casualties resulting from conflicts in the region, not only in Burkina Faso, but also in neighbouring Mali.5 From 2020 to 2021, violence linked to militant Islamist groups in the Sahel almost doubled.6 This grim trend looks set to continue, with civilians paying the price: the first six months of 2022 saw the killing of more civilians in the central Sahel than in all of 2021.7 So far in 2022, jihadist groups in Mali have killed roughly three times as many civilians as in 2021.8 These patterns confirm research noting that civilians are increasingly the targets of attacks in the region, and that conflicts are more commonly spreading across borders.9

It is a key point to consider the role that illicit economies are playing in fuelling and sustaining these growing conflicts in the Sahel and West Africa more broadly. Conflicts are unfolding across areas bisected by trafficking routes, and conflict actors are becoming key players in some illicit economies, as consumers, providers of protection, or direct participants. Understanding the intersection of conflict and illicit economy dynamics is therefore key to addressing the issue of growing civilian casualties.

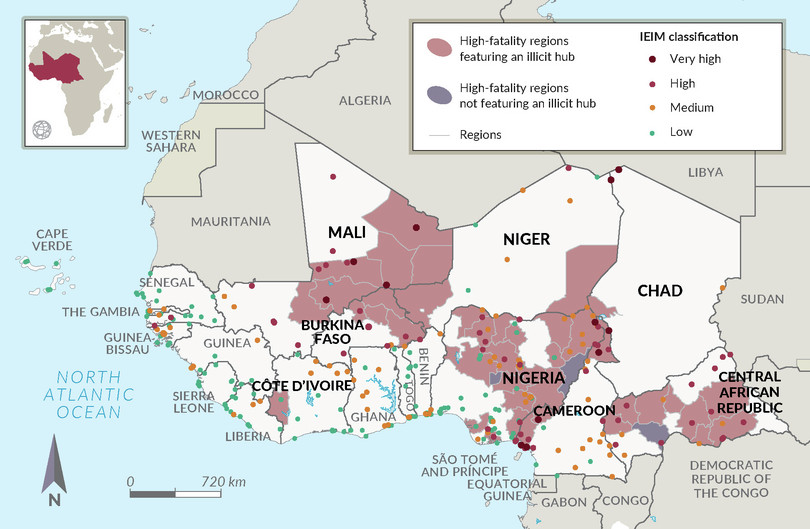

The GI-TOC’s illicit hub mapping initiative identified over 280 illicit hubs in West Africa, Cameroon, the Central African Republic (CAR) and Chad.10 The initiative pinpointed 65 locations in the region in which illicit economies are operating as significant vectors of conflict and instability.11 Almost all of the most violence-affected areas in West Africa – namely, areas where conflict fatalities have exceeded 500 between 2011 and 2021, referred to henceforth as ‘high-fatality regions’12 – are also home to at least one illicit hub. It is clear that there is an increasing geographic overlap between conflict areas and zones of illicit activity, which has implications not only for policymakers seeking to implement stabilization policies, but also for the prospective livelihoods of communities in the region. For more in-depth analysis of illicit hubs in West Africa, readers are encouraged to read the full report, ‘Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa’.13 Moreover, the online tool, which allows users to visually explore the 280 illicit hubs, as well as access further data related to conflict and instability, can be accessed at wea.globalinitiative.net/illicit-hub-mapping.

Dori, Burkina Faso. In July 2022, a bridge on the main road connecting Dori and Kaya was attacked by suspected jihadists, in one of many attacks targeting arterial roads connecting the capital Ouagadougou to cities in northern Burkina Faso.

Photo: Giles Clarke/UNOCHA via Getty Images

Geographic overlap between crime and conflict

Although Mali and Burkina Faso are among the most violence-affected countries in the region, violence against civilians at the hands of violent extremists, separatist groups and private military companies alike has been all too common in countries such as Nigeria, Cameroon and CAR. Of the 18 countries covered by the research,14 eight are home to at least one administrative region that has experienced particularly high levels of violence over the past decade, the so-called high-fatality regions, as introduced above. These include the Sahelian states of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, as well as Nigeria, Cameroon, CAR, Chad and Côte d’Ivoire.

We identified 46 high-fatality regions. Forty-three of them encompass at least one illicit hub, whether that be a hotspot, transit point or crime zone. In other words, nearly all of the most violence-affected regions in West Africa are also sites of illicit activity. Conflict areas and areas of instability more broadly, including spaces shaped by political volatility, often have a range of characteristics that allow illicit economies to flourish. For example, in conflict areas, state presence is often weak, enabling criminal actors to act with impunity. Furthermore, conflicts usually lead to a surge in demand for a range of illicit commodities, not least weapons, but also illicit drugs, such as Tramadol.15 A variety of legal economic activities also move into the grey zone, or become illicit, when armed groups take control of them – the exploitation of natural resources being a key example.16

Looking at the overlap from the opposite perspective, the findings of our research show that a significant percentage of illicit hubs are located in areas affected by high levels of conflict and violence. Of the 280 illicit hubs identified across West Africa, over 30% are located in high-fatality regions.

Figure 1 Most conflict-affected areas in West Africa encompass hubs of illicit economies.

Note: High-fatality regions are defined as administrative level 1 areas where conflict fatalities have exceeded 500 between 2011 and 2021. Crime zones are represented by the geographic coordinates of their central points.

Source: Lucia Bird and Lyes Tagziria, Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa, GI-TOC, September 2022, https://wea.globalinitiative.net/illicit-hub-mapping/map. Fatality data from ACLED.

Not only does the research show that conflict settings almost always encompass illicit economies (see Figure 1), but there is also a strong overlap between conflict-affected areas and illicit hubs that act as vectors of conflict and instability (although this is due in part to the nature of the Illicit Economies and Instability Monitor [IEIM], in which links to conflict dynamics play an important role). Twelve of the 280 illicit hubs were assessed to have a ‘very high’ score on the IEIM, a new metric designed to assess the degree to which illicit economies in identified illicit hubs drive conflict and instability. In other words, these 12 hubs were identified to play a very significant role in fuelling conflict and instability in the region. Of these 12 very high-IEIM hubs – which include the Lake Chad area and places such as Bamenda and Kousseri in Cameroon, which operate as transit points for arms and illicit drugs – 10 are located in high-fatality regions.17

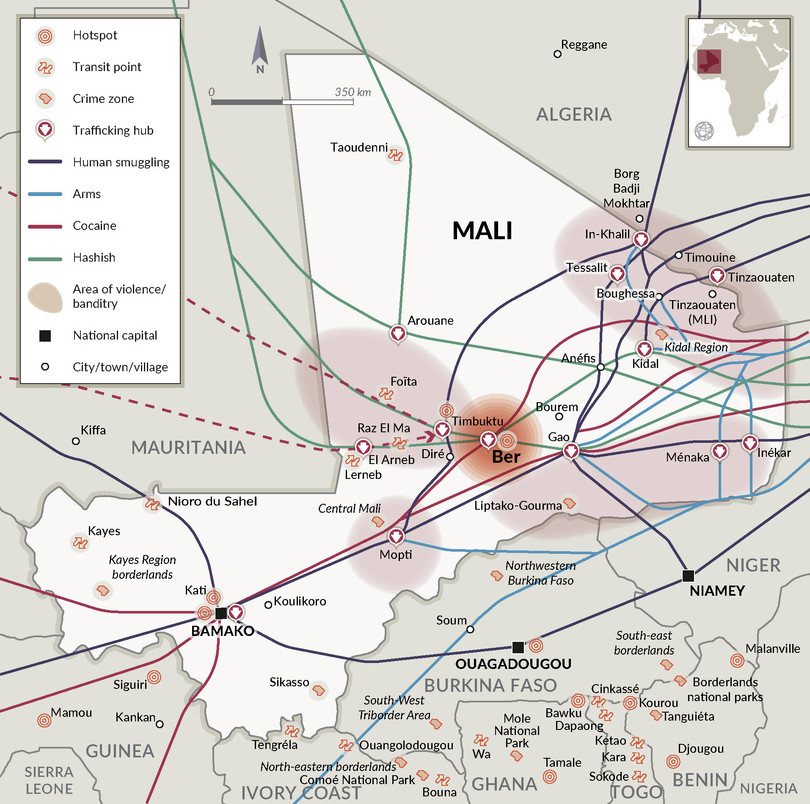

Liptako-Gourma, the tri-border area of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, is both one of these 12 very high-IEIM hubs, and is the region with the highest number of conflict fatalities in the 18 countries under study in the 10-year period between 2011 and 2021.18 Since the insurgency in northern Mali in 2012, violence has surged in the Liptako-Gourma region. Many illicit economies concentrated in the area have flourished, and major economies now include arms trafficking, cattle rustling, the trafficking of various drugs – primarily cannabis but also pharmaceuticals such as Tramadol and Diazepam, as well as cocaine – and the illicit gold trade, together with human smuggling, human trafficking and illicit trade and counterfeit goods.

Both JNIM and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara are prominent actors across a range of these thriving illicit economies, including cattle rustling, where they are key perpetrators. The presence and capacity of the states of Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso to provide security and basic services in the tri-border area have been impeded by the deterioration of the security situation in the region. While it is too early to assess the impact on state presence in the Liptako-Gourma area, there have been significant shifts in the conflict dynamics since the beginning of the French military withdrawal from Mali, which culminated in the complete departure of all French troops in August 2022. The northern city of Gao, for example, has been effectively cut off from the rest of the country since June due to a JNIM-imposed blockade of the town of Boni, located on the only road connecting the north of the country to the south.19

Armed groups have in turn benefitted from the weakening of state presence and drawn substantial revenues from illicit markets.20 In the Mopti region of the wider Liptako-Gourma area, for example, the uptick in cattle rustling that occurred in 2021 transpired in parallel with Mali’s growing political isolation and associated shifts in the country’s security landscape.21 Similarly, a more recently reported increase in cattle rustling in Ménaka has also been linked by close observers to the increasing instability in the context of the withdrawal of French troops.22

Certain illicit economies are more prominent in conflict settings

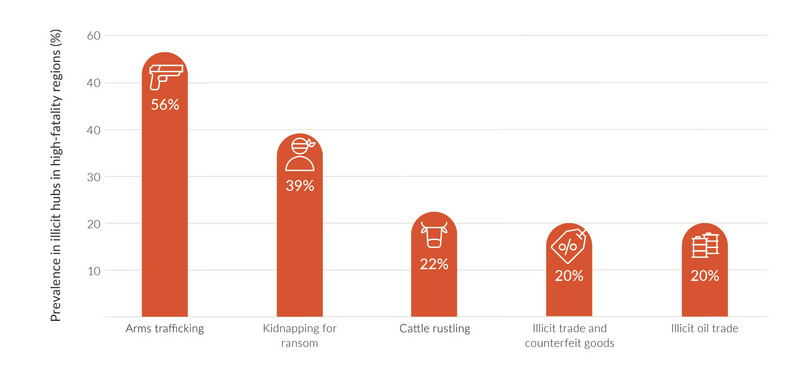

The prominence of certain illicit economies varies considerably across the IEIM spectrum, underscoring the differing relationships of illicit economies to conflict (see Figure 2). Cocaine displays the largest disparity, featuring as a major market far more commonly in low scoring hubs (33%) than in high- or very high-scoring hubs (8%). The differences are very similar when assessing the prevalence of illicit economies in areas with high levels of violence.

The cocaine trade only features in 9% of illicit hubs in high-fatality regions. These include Lerneb in Mali, through which consignments of cocaine (and cannabis resin) trafficked through Mauritania (as well as cocaine consignments trafficked into Mali via Kayes region) pass.23 These findings reflect the fact that, given the high monetary value of cocaine, trafficking networks often seek to avoid the most high-risk environments, such as the Sahel region, for example.24

Figure 2 Illicit economy prevalence in high- and very high-IEIM hubs compared to low-IEIM hubs.

Source: Lucia Bird and Lyes Tagziria, Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa, GI-TOC, September 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/GITOC-WEAObs-Organized-crime-and-instability-Mapping-illicit-hubs-in-West-Africa.pdf

By contrast, arms trafficking, is assessed to be a major market in more than half (54%) of all illicit hubs in the high- and very high-IEIM classifications, illustrating the strong link between the illicit market and conflict and instability. This finding is further supported by the fact that arms trafficking is by far the most prominent criminal market in illicit hubs in high-fatality areas, featuring in 56% of them.25

There exists a self-reinforcing relationship between arms trafficking and instability. The illicit economy amplifies violence by weaponizing conflict,26 while heightened insecurity fuels demand for weapons for self-protection, swelling the arms market. In Nigeria, for example, demand for weapons for self-protection has skyrocketed in response to unprecedented levels of violence perpetrated by armed bandits, particularly in the north of the country. This largely involves artisanal weapons that cater to the self-defence market in states such as Plateau, Kaduna, Katsina and Borno, where banditry is rife.27

The cycle of increasing demand for weapons amid growing instability is also illustrated by dynamics in the Malian city of Ber (see Figure 3), a hotspot for illicit economies assessed to have one of the highest IEIM scores in the region. Since 2020, Ber has been a key node in the transnational weapons trafficking industry, which is largely operated by actors from northern Mali’s Arab communities. Demand for arms has increased, particularly since 2016, from armed groups, self-defence militias, and communities for protection.28

Figure 3 Illicit flows through Ber, Mali.

Lucia Bird and Lyes Tagziria, Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa, GI-TOC, September 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/GITOC-WEAObs-Organized-crime-and-instability-Mapping-illicit-hubs-in-West-Africa.pdf

Arms trafficking is a major driver of conflict and violence, not only because weapons themselves are tools for violence, but because the illicit trade in weapons strengthens non-state actors in opposition to the state and contributes to the fragmentation of conflict. A key finding of the research is that arms trafficking is closely linked to several other illicit economies, which can be described as ‘accelerant markets’, which have a close link to conflict and instability, such as kidnapping for ransom and cattle rustling.29 Figure 4 shows the most prominent illicit economies in illicit hubs situated in high-fatality regions.

Figure 4 Most prominent illicit economies in ‘high-fatality region’ illicit hubs.

The fact that kidnapping for ransom (an illicit economy identified in just 17% of illicit hubs in West Africa) features in almost 40% of all illicit hubs in high-fatality regions underscores the role the criminal activity plays in conflict dynamics, particularly in Mali, Burkina Faso and Nigeria.30 Another illicit economy disproportionately pervasive in areas affected by high levels of conflict and violence is cattle rustling: 66% of illicit hubs featuring cattle rustling are located in high-fatality regions. This includes many cattle rustling hotspots throughout Nigeria, but also in the north-eastern borderlands of Côte d’Ivoire and the Central African towns of Kaga-Bandoro, Batangafo and Kabo, for example, where soldiers in the Central African army and armed group highwaymen known as coupeurs de route (‘road cutters’) have made significant profits through the illicit taxation of herders.

These links between certain illicit economies, arms trafficking and conflict and instability have important implications for policymakers seeking to anticipate and prevent violence, rather than merely respond to it. Illicit economies known to exacerbate community tensions, such as cattle rustling and kidnapping for ransom, should be regarded as indicators of potential future conflict. Responses specific to these illicit economies, both developmental and from a law enforcement perspective, should therefore be encouraged. This should include prioritizing areas in which illicit economies strongly link areas of greater stability with those in conflict, either through the flow of commodities or financing.

Notes

-

Al Jazeera, At least 35 civilians killed in Burkina Faso IED convoy blast, 6 September 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/9/6/dozens-civilians-killed-in-burkina-faso-blast-ied-convoy-blast. ↩

-

Although violent extremists affiliated with the Islamic State – namely, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) – are also key players in the conflict landscape in Burkina Faso, no ISGS attacks in this part of the country have been recorded to date. ↩

-

Arsène Kaboré and Sam Mednick, Suspected jihadi bomb hits convoy in Burkina Faso; 35 dead, AP News, 6 September 2022, https://apnews.com/article/islamic-state-group-ouagadougou-al-qaida-africa-burkina-faso-efdf50b9e0f9bd7ea4cabd274d3925bb. ↩

-

The Defense Post, 35 Civilians Killed in IED Blast in Burkina Faso, 6 September 2022, https://www.thedefensepost.com/2022/09/06/civilians-killed-ied-blast-burkina. ↩

-

Regarding the changing geography of conflict, and growing intensity of violence, see OECD Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC), The Geography of Conflict in North and West Africa, West African Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1787/02181039-en. ↩

-

Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Surge in militant Islamist violence in the Sahel dominates Africa’s fight against extremists, January 2022, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mig2022-01-surge-militant-islamist-violence-sahel-dominates-africa-fight-extremists/. ↩

-

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), 10 conflicts to worry about in 2022: The Sahel mid-year update, August 2022, https://acleddata.com/10-conflicts-to-worry-about-in-2022/sahel/mid-year-update/. ↩

-

Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Mali’s militant Islamist insurgency at Bamako’s doorstep, 29 August 2022, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mali-militant-islamist-insurgency-bamako-doorstep/. ↩

-

OECD/SWAC, The Geography of Conflict in North and West Africa, West African Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1787/02181039-en. ↩

-

To explore the online mapping tool, including further information for each of the 280 illicit hubs identified across the region, see https://wea.globalinitiative.net/illicit-hub-mapping/map. ↩

-

Lucia Bird and Lyes Tagziria, Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa, GI-TOC, September 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/GITOC-WEAObs-Organized-crime-and-instability-Mapping-illicit-hubs-in-West-Africa.pdf. ↩

-

As defined as at least 500 conflict fatalities between 2011 and 2021, using ACLED data; see https://acleddata.com/dashboard/#/dashboard. ↩

-

See https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/GITOC-WEAObs-Organized-crime-and-instability-Mapping-illicit-hubs-in-West-Africa.pdf. ↩

-

The 18 countries that fall under the scope of this research are: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, CAR, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo. ↩

-

Philip Obaji Jr, ‘If you take Tramadol away, you make Boko Haram weak’, African Arguments, 15 March 2019, https://africanarguments.org/2019/03/if-you-take-tramadol-away-you-make-boko-haram-weak/. ↩

-

Lucia Bird and Lyes Tagziria, Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa, GI-TOC, September 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/GITOC-WEAObs-Organized-crime-and-instability-Mapping-illicit-hubs-in-West-Africa.pdf. ↩

-

While the inclusion of a count of conflict fatalities in the IEIM model is a partial explanation for this finding, excluding the conflict fatalities indicator (which accounts for only 2 out of 30 points, representing under 7% of the overall IEIM score) from the calculation of the overall IEIM yields similar results. Of the 15 illicit hubs with the highest scores, excluding conflict fatalities, 12 are located in high-fatality regions. In other words, even removing conflict fatalities as an underlying indicator shows that illicit hubs that are significant vectors of conflict and instability are highly likely to be situated in conflict-affected areas. Furthermore, 33 of the 53 illicit hubs falling in the high-IEIM band, with IEIM scores between 15 and 20 (out of a maximum score of 30), are also found in high-fatality regions. Overall, the vast majority (66%) of high- and very high-IEIM hubs are situated in those regions that have experienced the most conflict fatalities over the past decade, underscoring the strong geographic overlap between conflict areas and illicit economies. ↩

-

See ACLED dashboard: https://acleddata.com/dashboard/#/dashboard. ↩

-

TV5 Monde, Mali: des dizaines de milliers de déplacés à Ménaka, un pont aérien vers Gao, 31 August 2022, https://information.tv5monde.com/afrique/mali-des-dizaines-de-milliers-de-deplaces-menaka-un-pont-aerien-vers-gao-469748. ↩

-

William Assanvo et al, Violent extremism, organised crime and local conflicts in Liptako-Gourma, Institute for Security Studies, 2019, https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/war-26-eng.pdf. ↩

-

Observatory of Illicit Economies in West Africa, Cattle rustling spikes in Mali amid increasing political isolation: Mopti region emerges as epicentre, Risk Bulletin – Issue 4, GI-TOC, June 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/GITOC-WEA-Obs-RB4.pdf. ↩

-

Interviews with civil society actors, Bamako and Ménaka, June to September 2022. ↩

-

See https://wea.globalinitiative.net/illicit-hub-mapping/map. ↩

-

Lucia Bird and Lyes Tagziria, Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa, GI-TOC, September 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/GITOC-WEAObs-Organized-crime-and-instability-Mapping-illicit-hubs-in-West-Africa.pdf. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Genevieve Jesse, Arms trafficking: Fueling conflict in the Sahel, International Affairs Review, 29, 2 (2021), 62–75, https://www.iar-gwu.org/print-archive/ikjtfxf3nmqgd0np1ht10mvkfron6n-bykaf-ey3hc-rfbxp-dpte8-klmp4. ↩

-

Alexandre Bish et al, The crime paradox: Illicit markets, violence and instability in Nigeria, GI-TOC, April 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/GI-TOC-Nigeria_The-crime-paradox-web.pdf. ↩

-

Lucia Bird and Lyes Tagziria, Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa, GI-TOC, September 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/GITOC-WEAObs-Organized-crime-and-instability-Mapping-illicit-hubs-in-West-Africa.pdf. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Observatory of Illicit Economies in West Africa, The strategic logic of kidnappings in Mali and Burkina Faso, Risk Bulletin – Issue 4, GI-TOC, June 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/GITOC-WEA-Obs-RB4.pdf. ↩