Armed bandits extort crop farmers amid dwindling alternative illicit revenue sources in Zamfara, north-western Nigeria.

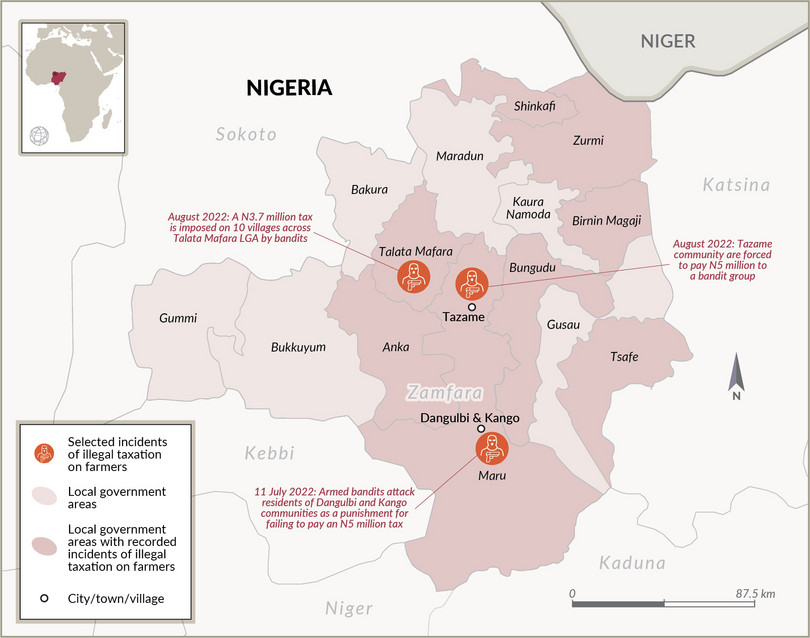

On 11 July 2022, armed bandits attacked residents of Dangulbi and Kango communities in Maru local government area (LGA) of Zamfara State, north-west Nigeria. Sixteen people were killed while working on their farms. A week before the attack, a bandit leader named Damina had imposed a 5 million naira (N) (US$11 650) farming tax on the communities, with a threat to exact it with force. Damina’s men carried out the killings after residents failed to raise the money.1

A growing trend, first tracked in 2019, sees bandits carry out a new form of extortion by taxing farming activities in Zamfara as a way of gaining revenue, as income from cattle rustling, a key source of financing, has dwindled. While bandits have also diversified revenue streams to include increased reliance on kidnap for ransom, the growing dependence on taxing farming presents a shift from drawing financing from illicit economies to the taxation of licit activities.

The threat of violence, and precedent deadly attacks, means most villages try to pay the sums demanded. Earlier this year, some 10 villages in Talata Marafa LGA escaped reprisal after raising N3.7 million (US$8 500) to pay the tax imposed on them by another group of bandits. The group had threatened to block access to farmlands and ransack the villages if the money was not paid by 30 August.2 In the neighbouring LGA of Bungudu, the Tazame community were forced to pay N5 million (US$11 650) to another bandit group in August 2022, before its members were allowed to have access to their farms.3

Six more LGAs (Anka, Shinkafi, Zurmi, Gusau, Birnin Magaji and Tsafe) are trapped in this web of extortion that appears to have emerged in Magami community (Gusau LGA) in 2019.4 According to a journalist based in Zamfara, bandits now ‘raise more money from imposing tax than abductions,’5 a point reiterated by a number of stakeholders. The spread of this practice since 2019 has significantly affected farmers’ livelihoods and poses a threat to food security.6 Furthermore, as revenue becomes increasingly dependent on territorial control, this growing practice could indicate escalation in conflicts in Zamfara as different groups vie for control.

Figure 1 Incidents of illegal taxation on farmers by bandits in Zamfara State.

Source: Information gathered from interviews in Zamfara State, September 2022.

In addition to illegally imposing taxes on farmers, bandits have become increasingly engaged directly in farming activities. This new development involves the confiscation of farmers’ lands by bandit groups, who subsequently use forced labour, mainly from local villagers, to cultivate the land. While communities in Maru noted the new trend in 2021, it has proliferated considerably since the beginning of 2022.7

So far, state responses have largely overlooked new trends, focusing more on responding to established (but dwindling) illicit economies, such as kidnap for ransom. A farmer in Dangulbi explained that the Nigerian government has stationed about 30 soldiers in the community as a protection against banditry, and yet bandits still go about collecting farming tax and seizing lands.8

A farmer returns from his farm in the village of Dangulbi, Zamfara State, the site of an armed bandit attack in July 2022.

Photo: supplied

Emergence of bandit farming extortion

Since 2011, Zamfara has been one of the states in north-western Nigeria most affected by banditry. The groups have drawn revenues from a range of illicit economies, and such financing is used to sustain the groups and to acquire weapons.9

Until 2019, the armed bandits had relied heavily on cattle rustling for revenue. While its impact is still widely felt across the state, cattle rustling as a source of income has become less profitable to bandits due to depletion of the cattle population, with many herds moved elsewhere as a result of insecurity.10

Bandits responded to dwindling revenues from cattle rustling by increasingly turning to kidnap for ransom. Rural communities have repeatedly reported a decrease in kidnapping incidents since the peak of 2021, which coincided with the marked surge in incidents of illegal farming taxation by bandit groups from early 2022.11

At its most rampant, between 2019 and 2021, kidnappings targeted primarily wealthy farmers and businessmen, from whom bandits collected millions of naira in ransom payments. However, the pool of possible targets for kidnappers shrank.12 The farmers and businessmen who had, in most cases, been kidnapped on more than one occasion by one or more groups of bandits, had either lost their wealth (as a result of previous ransom payments), fled, or been killed by their abductors for failing to raise the ransom fee.13 Between 2019 and 2020, a steady stream of villagers paid up to N350 000 (over US$800) to transporters to be relocated away from their communities.14

‘They have rustled all the livestock; if you go to 50 villages, you cannot find a goat. They moved to kidnapping and got people to flee. Those who remain and cannot run are the ones being taxed,’ a local official of a farmers’ association said regarding the emergence of bandit farming taxation.15

Data on abductions and forced disappearances from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), however, do not show a decrease in the number of kidnapping incidents between 2021 and 2022.16 Following meteoric yearly increases in the number of kidnapping incidents in Zamfara in 2020 and 2021, the kidnapping rate stagnated in 2022 (see Figure 2).17 While incidents remain high, a shrinking pool of possible targets is likely to have contributed to the decreased revenue that bandit groups have earned from kidnappings.

Figure 2 Kidnapping incidents in Zamfara and north-western Nigeria, 2018–2022.

Note: *As of 14 September. **Includes the following states: Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto and Zamfara.

Source: ACLED

The evidence suggests, therefore, that while kidnapping incidents across the state remain high, the ransoms solicited, and therefore the total revenue earned, by bandit groups have decreased.

The resulting shift to farming taxation since 2019 has helped channel millions of naira to bandit groups. From March to August 2022, bandits are estimated by members of local farming associations to have generated over N45 million (over US$100 000) in illicit tax revenue from farming communities in Dansadau district alone.18 These figures are expected to spike at harvest time, during November and December, when farmers have more money.

Local communities bear the costs of illicit farming taxation

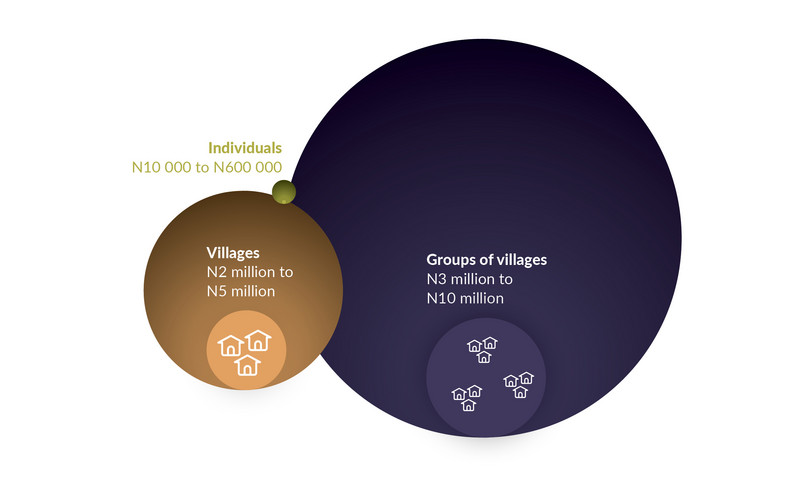

The illicit taxes imposed by bandits are levied on individuals, single villages and groups of villages, as highlighted in Figure 3. One farmer from Magami targeted by bandits said:

In 2021, they asked me to pay money before they would allow me to harvest my three farms. They threatened to burn all the crops that were due for harvest if I did not comply. So, I had to pay N170 000 [US$390] for a bean farm and N70 000 [US$160] and N30 000 [US$70] respectively for maize farms.19

Where individual farmers do not have the funds to pay the illegal tax, they are instead told to surrender 50% of their harvest to the bandits.20

Figure 3 Illegal taxation structures imposed by bandit groups.

Note: When individuals are targeted, a farmer is ordered to pay anywhere from N10 000 to N600 000, depending on the size of his farm (seen by the bandits as a proxy for overall wealth). In other instances, the tax – which is fixed between N2 million and N5 million– will be imposed on the village as a whole. Finally, bandits sometimes group together small villages and ask them to pay a lump sum, ranging from N3 million to N10 million.

Source: Information gathered from interviews with residents, journalists and law enforcement officials in Zamfara State, September 2022.

Where a tax is imposed on a village or group of villages, members of the villages bear the cost. Most of the times, adult male members are tasked with raising the amount, with each of them contributing a set amount based on their financial status in the community. For instance, to pay the N5 million requested by bandit kingpin Damina, some family heads in Dangulbi and Kango contributed between N10 000 and N60 000 (US$25–US$140) each.21

As a local community member explained:

In the end, the amount we raised fell short of our N5 million [US$11 650] target by N700 000 [US$1 600]. So, we asked for a loan from one member of our community to settle the debt with the bandits. We then asked each household to contribute an additional N1 000 [US$2.50] in order to pay back the loan. By the time we went back to our farms, over 40 days had passed and most of the crops were damaged by weed.22

These types of interruptions to farming activity are capable of crippling livelihoods in rural areas. The damage is compounded by the fact that often illegal taxes are imposed on the same communities several times (either by the same bandit group or a different one) within a short period.

The community leader in Talata Mafara, who spearheaded gathering the required payment of N3.7 million (US$8 500) to bandit leader Halilu Buzu in March 2022, said:

Last week, they asked us to buy another motorcycle for them. We have told them that we cannot raise another N370 000 [US$850]. Everyone here has overborrowed to meet their previous demands, but [the bandits] are unrelenting and are threatening to ban us from farming and to ransack our communities. If government does not intervene, we may be harmed. This is a new thing to us. Previously, they had rustled our cattle and repeated that last year, but this is the first time they are asking us to pay money before we go to our farms. Unfortunately, even after doing that, they are coming up with more and more demands. We can no longer afford their demands.23

Less than two weeks later, the community was again threatened by the bandits, forcing them to sleep in a nearby forest out of fear of violent reprisals.24

These developments are already taking a huge toll on the agrarian economy of Zamfara. A spokesperson for the All Farmers Association of Nigeria estimated that in Zamfara, about N43 billion (US$100 million) in potential farming revenue is lost to banditry,25 a huge consequence for a state with the highest percentage of the country’s poor and vulnerable.26

Bandits getting their hands dirty

As other sources of revenue have dwindled, farming now offers a significant available revenue stream, enabling bandits to sustain and potentially expand their activities. Since 2021, with a further upsurge since March 2022, bandits have increasingly established their own farms. Bandit farms are now common in all the eight LGAs where the groups impose taxes on farming.27 According to a resident of Anka, since the beginning of 2022, more farming activity is now carried out by bandit groups than by local farmers.28

Heightened military responses to bandit groups in neighbouring Kaduna, Sokoto, Kebbi, Katsina and Niger states are believed to be a key reason for which the bandits are returning to their bases in Zamfara.29 However, seizing farmlands may also be an attempt to assert territorial control and diversify income sources. Such tactics risk prolonging instability throughout the north-west as local communities arm themselves for protection and establish vigilante self-defence groups in response.

Since bandits have begun to farm themselves, residents of several LGAs have been forced to work on the farms belonging to the bandit leaders.30 Tracing the emergence of the practice, a local journalist said, ‘It started last year, when a bandit kingpin around the Magami, Dankurmi and Dansadau axis told farmers to work on his farm first, before they could work on their own. Since then, the practice has become rampant, and compliance is extremely high.’31

Bandit groups send emissaries to community leaders asking for a specific number of people to work on their farms. Villagers who fail to comply are rounded up, flogged and forced to work. While the practice has caused some people to vacate their villages in parts of the state, it is having an opposite effect in other areas, such as Anka.32 Some residents who fled their communities before 2021, to escape attacks and kidnappings, are now returning to cultivate their own lands, knowing that they will also be forced to work in farming for the bandits.

Security and livelihood implications

As with other forms of extortion, levying taxes on farmers is to a degree dependent on territorial control. As armed bandits increasingly rely on these rents, they may seek to exert greater control on territories and expand their territories of influence, triggering territorial tussles and turf wars, with potentially devastating impact on stability. Bandits would not only clash with rival groups in such territorial struggles, but also with local communities and security forces.

Villagers flee a bandit attack in Zamfara.

Photo: Shehu Umar

Furthermore, with heavy taxes and levies, farming looks set to become less lucrative. Some local farmers may abandon farming and seek alternative livelihoods. This could enable bandit groups to capture additional territory, and revenue flows, with an overall criminalization of farming practices having potentially significant implications for food security.

The government’s response to the armed bandit crisis in Zamfara has thus far largely involved a military approach. This strategy often helps to temporarily lull the problem, but relief frequently proves temporary. In December 2021, Zamfara governor Bello Matawalle, at a meeting with former bandits and law enforcement, adopted a different approach by appealing to bandit groups to allow farmers to harvest their crops.33

The communities most affected by banditry are clear on the need for policies that will improve livelihoods in rural areas. Poverty is believed to be the driving factor behind banditry. According to one local community member, informants will accept as little as N5 000 (just over US$10) to spy on their own community, such is the scarcity of economic opportunity.34 Moreover, the feeling among many local communities is that the authorities are failing to hold the bandits to account, allowing them to act with impunity.35 If there is any hope of improvement in the security dynamics in Zamfara, it must start with the application of the rule of law.

Notes

-

Interview with a farmer in Dangulbi, Maru LGA, Zamfara, 9 September 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a community leader in Gwaram, Talata Mafara LGA, Zamfara, 10 September 2022. ↩

-

Interview with an official of a local branch of a farmers’ association, Zamfara, 8 September 2022. ↩

-

Interview with an official of a local branch of a farmers’ association, Zamfara, 8 September 2022; interview with a journalist in Gusau, Zamfara, 9 September 2022; Maiharaji Altine, Reign of terror: Zamfara bandits take over villages, impose harvest levies, burn crops, Punch, 26 November 2021, https://punchng.com/reign-of-terror-zamfara-bandits-take-over-villages-impose-harvest-levies-burn-crops/. ↩

-

Interview with a journalist in Gusau, Zamfara, 9 September 2022. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with a vigilante leader in Magami, Maru LGA, Zamfara, 8 September 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a farmer in Dangulbi, Maru LGA, Zamfara, 9 September 2022. ↩

-

Observatory of Illicit Economies in West Africa, In north-western Nigeria, violence carried out by bandit groups has escalated so fast that killings now rival those that take place in Borno state, where extremist groups hold sway, Risk Bulletin – Issue 1, GI-TOC, September 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/WEA-Obs-RB1-GITOC.pdf. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Conclusions drawn from fieldwork in numerous communities across Zamfara, including Dangulbi, Kango and Magami in Maru LGA, as well as communities in Anka LGA. ↩

-

In addition to a shrinking pool of possible targets, media reports suggest that government action to block telecommunications networks in parts of north-western Nigeria, in a bid to stem banditry and kidnappings, contributed to the decline in kidnap for ransom, as bandits found it increasingly difficult to make ransom calls. See Maiharaji Altine, Reign of terror: Zamfara bandits take over villages, impose harvest levies, burn crops, Punch, 26 November 2021, https://punchng.com/reign-of-terror-zamfara-bandits-take-over-villages-impose-harvest-levies-burn-crops/. ↩

-

Interview with a vigilante leader in Magami, Maru LGA, Zamfara, 8 September 2022; interview with a journalist in Gusau, Zamfara, 9 September 2022. ↩

-

Interview with an elderly kidnapping victim (who paid N350 000 to a truck driver to be relocated out of the community, after he escaped from bandits. His two brothers paid various amounts in ransom before they were released), Magami, Maru LGA, Zamfara, 8 September 2022. ↩

-

Interview with an official of a local branch of a farmers’ association, Zamfara, 9 September 2022; interview with a journalist in Gusau, Zamfara, 9 September 2022. ↩

-

ACLED dashboard: https://acleddata.com/dashboard/#/dashboard. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with an official of a local branch of a farmers’ association, Zamfara, 9 September 2022; interview with a journalist in Gusau, Zamfara, 9 September 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a farmer in Magami, Maru LGA, 8 September 2022. ↩

-

Interview with an official of a local branch of a farmers’ association, Zamfara, 9 September 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a farmer in Dangulbi, Maru LGA, Zamfara, 9 September 2022. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with a community leader in Gwaram, Talata Mafara LGA, Zamfara, 10 September 2022.’ ↩

-

Interview with a community leader in Gwaram, Talata Mafara LGA, Zamfara, 20 September 2022, by phone. ↩

-

Oluwafemi Morgan and Daniel Ayantoye, Insecurity: Zamfara farmers negotiate with bandits today, Punch, 20 August 2022, https://punchng.com/insecurity-zamfara-farmers-negotiate-with-bandits-today/. ↩

-

Sam Tunji, Zamfara home to highest number of poor Nigerians – NSR, Punch, 23 June 2021, https://punchng.com/zamfara-home-to-highest-number-of-poor-nigerians-nsr/. According to data released in 2021 by the National Social Registry, a Nigerian government and World Bank partnership, the state has 3 836 484 people from 825 337 households. ↩

-

Interview with a journalist in Gusau, Zamfara, 9 September 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a businessman with close ties to local traditional rulers, Anka, Zamfara, 10 September 2022. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

These include Anka, Tsafe, Bukkuyum, Maru, Talata Mafara, Birnin Magaji, Shinkafi, Zurmi and Bungudu. ↩

-

Interview with a journalist in Gusau, Zamfara, 9 September 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a businessman in Anka, Zamfara, 10 September 2022. The businessman has a close link to the traditional institution in the area. ↩

-

Interview with a journalist in Gusau, Zamfara, 9 September 2022. ↩

-

Interview with an official of a local branch of a farmers’ association, Zamfara, 9 September 2022. ↩

-

Conclusions drawn from interviews with several sources, including officials of a local branch of a farmers’ association and a farmer in Dangulbi, September 2022. ↩