As Casamance rebels are weakened, is the Niokolo Koba National Park a potential fallback zone?

Located in southern Senegal, between Gambia and Guinea Bissau, the Casamance region has since the early 1980s been rocked by a separatist conflict between the Mouvement des forces démocratiques de Casamance (Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance, MFDC) and the Senegalese state. Recent developments appear to have dramatically altered the balance of power in West Africa’s most longstanding conflict.

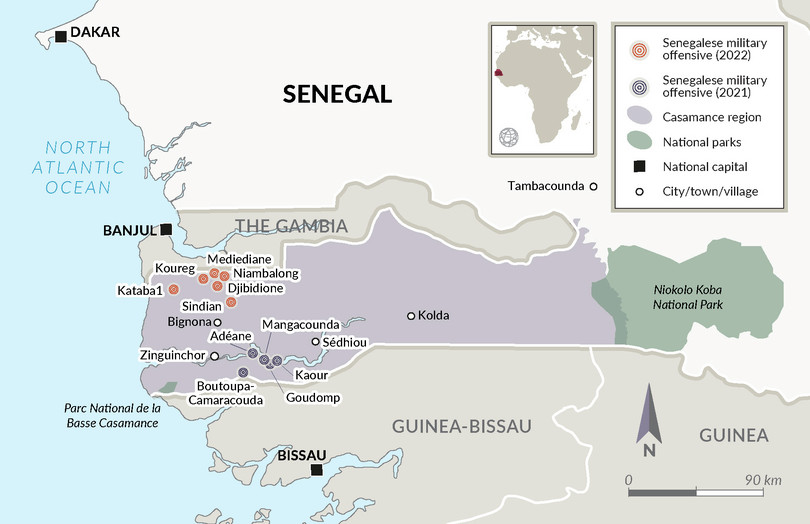

Since early 2021, the Senegalese authorities have launched a series of military offensives against the MFDC rebels. In March 2022, the Senegalese army opened a new front in northern Casamance, in the department of Bignona. The objective of this operation, according to a statement released by the Ministry of Armed Forces, was to dismantle the bases of one MFDC faction led by Salif Sadio, stressing the need to ensure ‘territorial integrity’, as well as to eliminate all criminal groups carrying out illicit activities in the area.1 This operation resulted in the dismantling of almost all MFDC bases in the region – potentially a significant turning point, divorcing the rebels from traditional revenue streams linked to illicit economies in the Casamance region.

The Casamance separatists have long been involved in numerous illicit economies, exploiting the abundance of natural resources in the country’s southern region to finance their operations. Contested state control has been one enabling factor for the emergence of Casamance as a key transit point for a wide range of illicit flows between Guinea-Bissau, Senegal and Gambia, including cocaine.2 The trafficking of timber and cannabis, in addition to wildlife products, has been a mainstay of the MFDC’s revenue streams over the past two decades.3

However, the rebels have been significantly weakened by law enforcement action against them since 2021. Across West Africa, armed actors targeted by military operations have increasingly turned to national parks as fallback zones. For example, the W-Arly-Pendjari (WAP) complex in the tri-border area between Burkina Faso, Benin and Niger has long operated as a fallback zone and safe haven for Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (Group to Support Islam and Muslims) elements, resting after offensives from international actors in Mali.

Will the decisive military offensives, and weakening of traditional fallback areas in Guinea-Bissau and Gambia, mark the beginning of the end for the MFDC? Or will the rebels merely displace geographically, searching for alternative sources of funding? If the latter, will the regional trend be replicated here, and will Niokolo Koba, one of the largest national parks in West Africa located fewer than 400 kilometres from the Casamance region, become the armed group’s new home?

Renewed Senegalese military offensive pushes Casamance rebels to breaking point

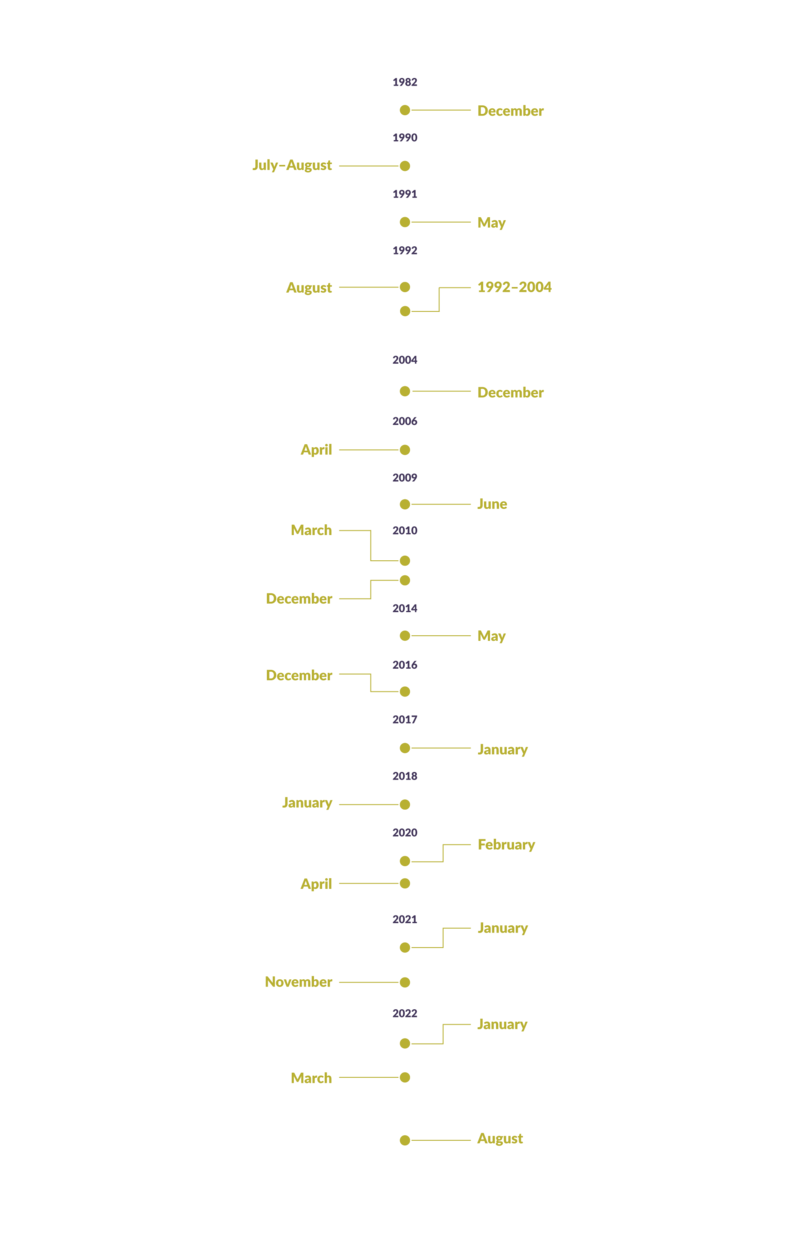

Created in 1947, the MFDC was founded as a political party, before becoming a separatist movement in 1982, seeking independence for the Casamance region.4 An August 2022 peace agreement was preceded by six other ceasefires and peace agreements between the MFDC and the Senegalese government since 1991.5 None brought peace; instead, these agreements caused tensions within the MFDC and led to the creation of several factions. In 1991, the armed wing of the independence group split into two factions: the Southern Front and Northern Front. Today, the two fronts have several factions, the most important being those of Salif Sadio and César Atoute Badiate.

A January 2021 Senegalese offensive against the rebel factions in the south led to the dismantling of at least three rebel bases, known respectively as ‘2’, ‘9’ and ‘Sikoun’.6 Authorities seized large stocks of ammunition, mortars, rocket launchers, rifles and motorcycles and destroyed cannabis fields in the area controlled by the rebels.7

A March 2022 offensive in the northern area of the Casamance, in the Bignona department, targeted rebel bases scattered on the border with Gambia. A key objective of the operation was also to put an end to the illicit trafficking of timber in the Casamance region.8 This offensive dismantled most of the rebels’ bases in the area,9 and seized important quantities of weapons and various materials, including stolen vehicles.10 While most of the fighters reportedly fled across the border to Gambia, many of them returned to their respective villages shortly after.11

Figure 1 Senegalese military offensives against MFDC rebels.

Source: Data drawn from available media sources.

Rebel-led illicit economies may be dwindling

Since the early 2000s, MFDC rebels have been tapping into the natural resources available in the Casamance region to finance their operations. The trafficking of timber from the forests of Casamance has been the group’s main source of funding.12 The lack of state reach in areas of the Casamance region bordering Gambia and Guinea-Bissau allowed the MFDC to consolidate its presence there and allowed them to engage in extensive timber trafficking.13

The MFDC rebels granted timber licences to Senegalese and Gambian traffickers, a prerogative that should belong exclusively to the Senegalese state.14 To transport timber purchased in the rebel-controlled territories to Gambia, buyers had to pay for an export document issued by the rebels.15 Timber trafficking is estimated to have generated US$19.5 million between 2010 and 2014, much of which would have benefited the factions involved in this criminal activity.16

In the past, rebels could easily retreat to Guinea-Bissau or Gambia when there were clashes with the Senegalese army, as they enjoyed the protection of important actors in both countries. Yahya Jammeh, the long-time ruler of Gambia, was reportedly one of the biggest supporters of the Casamance rebels.17 His exile in 2017 greatly weakened the MFDC. Similarly, in Guinea-Bissau, the MFDC rebels had the support of some army officers.18

The regime changes in Gambia in 2017 and Guinea-Bissau in 2021, which brought Adama Barrow and Umaro Sissoco Embaló to power respectively, redefined the balance of power and offered an important advantage to the state of Senegal in its operations against the Casamance rebels. The close relationship of Macky Sall, president of the Senegalese republic, to both leaders has translated into greater ability for Senegalese troops to pursue rebels into traditional havens in Guinea-Bissau and Gambia.19

Evolution of the Casamance separatist conflict

Niokolo Koba National Park as a potential MFDC fallback zone?

Following the dismantling of their bases, seizure of their weapons and weakening of traditional havens, the MFDC’s ability to translate territorial influence into revenue streams from illicit economies may be weakened. For now, the MFDC rebels appear to have no intention of laying down their arms. A specialist of the Casamance conflict told the GI-TOC that he believes the rebels will return sooner or later.20 But deprived of their natural bases in Casamance, the rebels will need new bases.

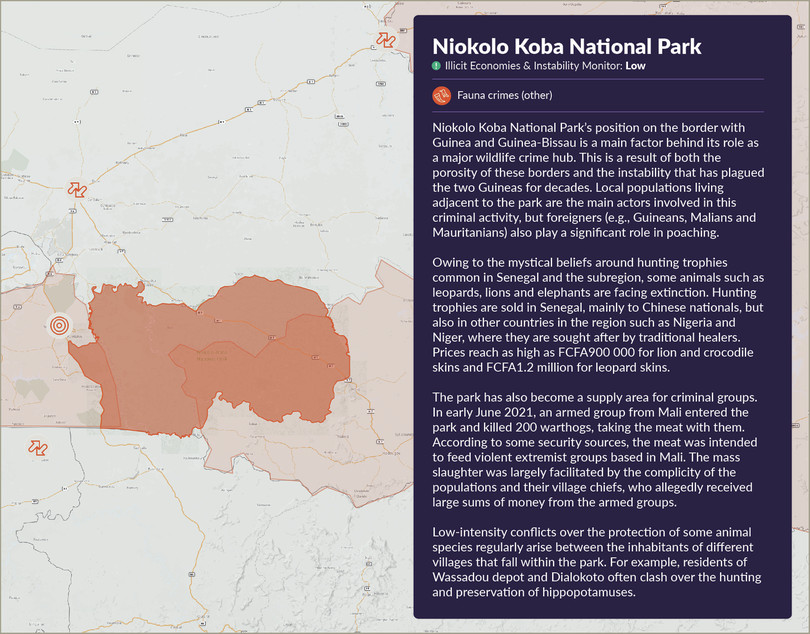

The Niokolo Koba National Park offers significant opportunities to the rebels as a new fallback zone. Located in south-eastern Senegal in the region of Tambacounda, on the banks of the Gambia River, Niokolo Koba National Park is one of the largest parks in West Africa, with an area of 913 000 hectares.21

The Niokolo Koba National Park, one of the largest parks in West Africa.

Photo: BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Figure 2 Niokolo Koba National Park as an illicit hub.

Source: Lucia Bird and Lyes Tagziria, Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa, GI-TOC, September 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/GITOC-WEAObs-Organized-crime-and-instability-Mapping-illicit-hubs-in-West-Africa-1.pdf

Boasting an abundance of natural resources and rich in biodiversity, while strategically located close to the border with Mali and Guinea, the Niokolo Koba National Park could offer numerous possibilities to rebel groups to draw revenues from illicit activities they have long relied on, including the illicit trade in timber, cannabis and wildlife products. Furthermore, the geographic configuration of the park, presenting access difficulties, heavy forests stymying air surveillance, and a low level of on-land surveillance (only 164 rangers patrol the entire park), makes the park an obvious choice for armed groups to conceal themselves and launch attacks of their own.22

Niokolo Koba is already often subject to incursions by unidentified armed groups, some believed to have crossed the border from Mali.23 Exploiting the porous borders and the low level of park surveillance, these actors have engaged in the poaching of rare animal species, often in complicity with the villagers living in the vicinity, who act as informants, refusing to share information with law enforcement agents and offering shelter when required.24 The sale of meat and animal trophies is a very lucrative activity that has been known to finance armed groups across Africa. In Uganda, for example, the trafficking and sale of ivory was the main source of funding for the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA).25

Furthermore, owing to a strong belief in the mystical virtues of these hunting spoils, the skins of certain animals can be sold for between FCFA500 000 and FCFA1 200 000 (US$750–US$1 800), depending on the size and type of animal.26 The skin of a Derby Eland – the largest species of antelope and the park’s emblem – which is highly prized by Malian and Nigerian traditional healers, is sold for up to FCFA300 000 (US$450) on the black market. The teeth and claws of lions, also highly sought after by Nigerien marabouts, are sold for FCFA250 000 (US$ 375) each.27

Gold mines in the park could also offer a source of revenue. According to the Senegalese authorities,28 part of the park in the department of Kédougou is rich in mineral resources, and gold in particular. Gold reserves in the park have recently been subject to illegal exploitation by criminal networks. In 2019, police in Kédougou arrested three Ghanaian nationals and 13 Chinese nationals for illegal gold mining, together with the director and deputy director of the Niokolo Koba National Park and other regional government officials for their involvement in the illicit activity.29

A boom in artisanal gold mining throughout large parts of the Sahel region over the past decade has provided new revenue streams for conflict actors, particularly in Mali and Burkina Faso.30 Gold sites in protected areas across the region – including in Comoé National Park in northern Côte d’Ivoire, and the WAP complex – have been identified as potential sources of revenue for armed groups increasingly operating in the northern areas of the littoral states. Regional precedent suggests that the Niokolo Koba National Park is currently vulnerable to exploitation by the MFDC, as their traditional revenue streams and areas of territorial control diminish.

In countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger, military and law enforcement action against violent extremist groups and other armed groups has seen these groups retreat into national parks, such as the Comoé National Park and the WAP complex. These national parks are used by armed groups as strategic sanctuaries and as bases from which to launch attacks.31 In Côte d’Ivoire’s Comoé National Park, jihadist elements aim to control access to the park, in order to use it for concealment and training and as a base for rest and recuperation. Furthermore, jihadist groups have reportedly promised mining communities situated inside the park protection and access to the gold as a form of governance arrangement.32

It is clear, therefore, that the Niokolo Koba National Park is an area at risk of being exploited by MFDC separatists. However, that the rebels are likely to be able to engage in illicit activities predicated on the natural resources of the national park, providing them with much-needed financial resources, is not the only risk. As has been experienced in in other parts of West Africa, not just in Côte d’Ivoire as outlined above but in the Sahel region too, jihadist groups have used national parks and wildlife reserves as a means to ingratiate themselves with the local population by allowing residents to engage in economic activity prohibited by the state, including logging and artisanal gold mining.33 If MFDC rebels are allowed to put down roots in the Niokolo Koba National Park, there is a risk that the park will experience the same fate.

Notes

-

Ministry of the Armed Forces, Communiqué de presse: Opération de sécurisation en Zone militaire n°5, March 2022, https://www.forcesarmees.gouv.sn/communiques/operation-de-securisation-en-zone-militaire-ndeg5. ↩

-

For further analysis of the role played by the Casamance region in subregional illicit ecosystems, see Lucia Bird, West Africa’s cocaine corridor: Building a subregional response, GI-TOC, April 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/west-africas-cocaine-corridor. ↩

-

Mehdi Ba, Senegal: When timber trafficking fuels rebellion in Casamance, The Africa Report, 13 July 2022, https://www.theafricareport.com/218403/senegal-when-timber-trafficking-fuels-rebellion-in-casamance. ↩

-

Perspective Monde, Début d’un conflit dans la région de la Casamance, au Sénégal, Université de Sherbrooke, 26 December 1982, https://perspective.usherbrooke.ca/bilan/servlet/BMEve/1260. ↩

-

Africa24, Sénégal: un accord de paix signé entre l’Etat et la rébellion casamançaise, 9 August 2022, https://africa24tv.com/senegal-un-accord-de-paix-signe-entre-letat-et-la-rebellion-casamancaise/. ↩

-

Pauline Le Troquier, Rébellion. En Casamance, une offensive de l’armée sénégalaise violente mais passée sous silence, Courier International, 5 February 2021, https://www.courrierinternational.com/article/rebellion-en-casamance-une-offensive-de-larmee-senegalaise-violente-mais-passee-sous-silence. ↩

-

Le Monde, L’armée sénégalaise annonce avoir pris le contrôle de trois bases rebelles en Casamance, 10 February 2021, https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2021/02/10/l-armee-senegalaise-annonce-avoir-pris-le-controle-de-trois-bases-rebelles-en-casamance_6069479_3212.html. ↩

-

Mamadou Alpha Diallo, L’offensive de l’armée va t-elle fragiliser les acquis de la paix en Casamance?, DW, 23 March 2022, https://www.dw.com/fr/sénégal-casamance-rebelles-offensive-militaire/a-61239094. ↩

-

Including those in Bakingaye, Djilanfale, Guikess, Katama, Katinoro, Karounor, Tampindo/Kanfounda and Younor. See Ouestaf, Sénégal: l’armée veut en finir avec le MFDC, 24 March 2022, https://www.ouestaf.com/senegal-larmee-veut-en-finir-avec-le-mfdc/. ↩

-

Le Quotidien, Bilan de la mission de sécurisation en Casamance: les rebelles désertent de leurs factions, 23 March 2022, https://lequotidien.sn/bilan-de-la-mission-de-securisation-en-casamance-les-rebelles-desertent-de-leurs-factions/. ↩

-

Interview with a specialist of the Casamance conflict, September 2022. ↩

-

Mouhamadou Kane, The silent destruction of Senegal’s last forests, ENACT, January 2019, https://enactafrica.org/enact-observer/the-silent-destruction-of-senegals-last-forests. ↩

-

Interview with a University of Assane Seck, Ziguinchor, lecturer and expert in the Casamance conflict and timber trafficking, September 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a water and forest agent in Casamance, February 2021. ↩

-

Environmental Investigation Agency, Cashing-in on chaos: How traffickers, corrupt officials, and shipping lines in The Gambia have profited from Senegal’s conflict timber, June 2020, https://content.eia-global.org/assets/2020/06/EIA-Cashing-In-On-Chaos-HiRes.pdf. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Lucia Bird and A. Gomes, Deep-rooted interests: Licensing illicit logging in Guinea-Bissau, GI-TOC, May 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/illicit-logging-guinea-bissau/. ↩

-

Goree Institute, Casamance: aux sources du conflit, 14 February 2022, https://goreeinstitut.org/casamance-aux-sources-du-conflit/. ↩

-

President Embaló granted unprecedented (and controversial) permission to Senegalese troops to pursue rebels into Bissau-Guinean territory in March 2021. For further discussion of President Embaló’s decision, and the possible links between this permission and the reported attempted coup in Bissau in February 2022, see Lucia Bird, Cocaine politics in West Africa: Guinea-Bissau’s protection networks, GI-TOC, July 2022, (https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GITOC-WEA-Obs-Cocaine-politics-in-West-Africa-Guinea-Bissaus-protection-networks.pdf. Since 2019, Senegalese security forces have exercised the right to pursue illicit loggers who have acted illegally in the Casamance, in Gambia; see BBC, Trafic de bois: le Sénégal exerce un droit de poursuite en Gambie, 11 May 2018, https://www.bbc.com/afrique/region-44082923. ↩

-

Interview with a University of Assane Seck, Ziguinchor, lecturer and expert in the Casamance conflict and timber trafficking, September 2022. ↩

-

UNESCO, Niokolo-Koba National Park, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/153/. ↩

-

Interview with a park official, August 2022. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Aislinn Laing, LRA warlord Joseph Kony uses ivory trade to buy arms, The Telegraph, 12 January 2016,https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/joseph-kony/12066467/LRA-warlord-Joseph-Kony-uses-ivory-trade-to-buy-arms.html. ↩

-

Interview with an investigator from an NGO specializing in fauna crime in Senegal, July 2022. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with security and mining authorities, Dakar and Kédougou, February 2021 to August 2022. ↩

-

Abdoulaye Barro, Exploitation illégale d’or à Bandé Ethiess, la Gendarmerie de Kédougou arrete 20 personnes, Sudestinfo, 3 June 2019, https://sudestinfo.com/exploitation-illegale-dor-a-bande-ethiess-la-gendarmerie-de-kedougou-arrete-20-personnes/. ↩

-

Peter Tinti, Whose crime is it anyway? Organized crime and international stabilization efforts in Mali, GI-TOC, February 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Whose-crime-is-it-anyway-web.pdf. ↩

-

Lucia Bird and Lyes Tagziria, Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa, GI-TOC, September 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/GITOC-WEAObs-Organized-crime-and-instability-Mapping-illicit-hubs-in-West-Africa-1.pdf. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Peter Tinti, Whose crime is it anyway? Organized crime and international stabilization efforts in Mali, GI-TOC, February 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Whose-crime-is-it-anyway-web.pdf. ↩