Is wildlife crime in Cameroon’s Bouba Ndjida National Park financing an emerging separatist group in the north?

On 12 June 2022, in a forest just outside Sorombeo in north-eastern Cameroon, clashes erupted between elements of the bataillon d’intervention rapide (4th Rapid Intervention Battalion, BIR), an elite unit of the Cameroonian Armed Forces created to tackle the threat of terrorism and armed groups, and members of the separatist rebel group Mouvement de libération du Cameroun (Movement for the Liberation of Cameroon, MLC). The military operation was launched after the BIR received information that armed men were present in the Sorombeo area, situated fewer than 30 kilometres from the Bouba Ndjida National Park. According to members of the BIR, around 10 MLC members armed with Kalashnikovs were involved in the incident. Although three of the rebels were injured, and subsequently arrested, the remaining assailants were able to flee across the border into Chad.1

The BIR and members of the MLC were involved in a similar clash in the Bouba Ndjida National Park a year earlier, with information gathered from the resulting arrests showing that the rebels had been engaging in elephant poaching in the park. Armed groups participating in the illicit wildlife trade as a source of revenue is not a new phenomenon. The Sudanese Janjaweed militia, and criminal actors linked to them, have been the primary actors involved in the poaching of and illicit trade in animals in the Bouba Ndjida National Park over the past two decades.2

Poaching by the Janjaweed in Bouba Ndjida appears to have dwindled, with no recorded incidents since June 2021, when militiamen were intercepted in the park by the BIR and forced to flee.3 This decrease is largely attributed to an enhanced military presence in the area. Yet will we see the MLC – the new rebel group emerging in the already fragile political and security context of Cameroon – increasingly targeting wildlife in the national park to finance itself? A number of wildlife trafficking experts in Cameroon have informed the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC) that they have no indication that the MLC is involved in poaching in the park.4 Yet, information received directly from the military units stationed in and around Bouba Ndjida suggests otherwise, arguably pointing to a nascent phenomenon.

Nascent rebel group entering the poaching game?

In August 2020, a video emerged online, shared widely on social media, in which a new military outfit introduced themselves as the MLC.5 In the video, the self-proclaimed coordinator of the group announced that their primary objective was to militarily combat the regime of Cameroon’s long-serving ruler, Paul Biya. The group also seeks the independence of northern Cameroon. The MLC was reportedly established just across the border in Chad but operates across the tri-border area between Cameroon, Chad and the Central African Republic (CAR), and is led by a man known as General Fafour.6

According to leading figures in the MLC, the movement is driven by several grievances against the Cameroonian government, including attacks on the pastoralist community from which many of its members hail, as well as a perception of marginalization more broadly. In March 2021, an MLC spokesperson reiterated the group’s intention to take up arms against the Biya regime, whom they have accused of embezzlement and corruption, warning the ‘armed civilians’ that have been recruited by the state to fight the MLC to stand aside, lest their villages be burned down.7

In a country facing two separate major conflicts – the anglophone crisis in the south-west and the Boko Haram insurgency in the far north – the current threat posed by the MLC to Cameroon’s national security is by no means comparable. In April 2021, Cameroon’s Minister of Defence, Joseph Beti Assomo, told the country’s parliament that while the MLC posed no threat, investigations into the group were underway.8 This notwithstanding, there have been clashes between elements of the MLC and Cameroonian military and law enforcement in and around the Bouba Ndjida National Park.

National parks and other natural areas, such as forests and wildlife reserves, are increasingly being used as strategic sanctuaries by armed actors in West Africa, often as bases from which to launch attacks.9 Furthermore, criminal actors operating in and around the parks are often involved in illicit economies, either directly (as a source of financing) or by allowing local residents to engage in informal economic activity (in order to earn the trust and support of local populations).10 Figure 1 shows national parks and forests that have been identified as key hubs of illicit activity as part of the GI-TOC’s illicit hub mapping initiative.11

Figure 1 National parks, reserves and forests in West Africa identified as illicit hubs.

Note: Although not included in this map, several other broader crime zones also incorporate one or more national parks, reserves or forests that may be sites of illicit activity.

Source: Lucia Bird and Lyes Tagziria, Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa, GI-TOC, September 2022, https://wea.globalinitiative.net/illicit-hub-mapping/map

The Bouba Ndjida National Park, located close to Cameroon’s borders with Chad and CAR, is home to important reserves of faunal, floral and mining biodiversity, with over 25 species of large and medium-sized mammals, including lions, antelopes, giraffes and, crucially, elephants. And as with many areas rich in biodiversity, the national park has experienced high levels of poaching. The elephant population, once the park’s star attraction, has significantly diminished following acts of poaching orchestrated by cross-border criminal groups. Although data on elephant poaching across the country is hard to come by, according to park officials, approximately 480 elephants were killed in Bouba Ndjida between 2003 and 2021.12

In response to the slaughter of over 200 elephants in the park by suspected Janjaweed militants in 2012, Operation ‘Peace at Bouba Ndjida’ was launched, under the command of the BIR. Each year, the operation is activated on 1 December and runs until May, when the beginning of the rainy season makes excursions into the national park unfeasible (for law enforcement and the poachers) due to flooding. In June 2021, following the yearly dismantling of the operation, five elephant carcasses were found in the park by conservation eco-guards.13

Operation ‘Peace at Bouba Ndjida’ departs towards Bouba Ndjida National Park, 2021.

Photo: Moussa Bobbo

The search operation activated by elements of the 42nd Light Intervention Unit (LIU) of the 4th BIR stationed in Ray-Bouba, a city located around 40 kilometres from the national park, resulted in a clash with the combatants of the rebel group MLC.14 Further elephant carcasses were found the following month, provoking another confrontation with elements of the MLC.

As one MLC member and poacher who was arrested as a result explained, ‘We are a recent rebel group that seeks to establish itself, [but] we do not yet have the means to recruit and maintain enough combatants.’15 According to him, the illicit trade in animal products sourced in Bouba Ndjida is a temporary activity for the group while they try to establish other sustainable sources of financing: ‘Since we have mastered the bush in this park, poaching appears to us as a fast activity,’ he said.16

If, going forward, the MLC does establish the illegal wildlife trade as a main source of financing, the history of illegal activity perpetrated by other armed groups in the Bouba Ndjida National Park, such as the Sudanese Janjaweed, can give us an indication of the possible future dynamics.

Janjaweed poaching in Bouba Ndjida National Park

Armed groups have had a presence in Cameroon’s national parks and forest areas for the past two decades. The poaching of rare animal species by armed actors is driven in part by the fact that they are highly coveted by armed criminal groups seeking to finance their activity.17 The national park is situated at the gateway to Chad, CAR and, to a lesser extent, Sudan – all countries with turbulent socio-political pasts (and presents). It is no coincidence that the rise in elephant poaching incidents in the park since 2003 took place at the same time as the start of the crisis in Darfur, which was then followed by the acceleration of conflicts in CAR (2004) and Chad (2005).

In 2012, over 200 elephants were poached by the Sudanese Janjaweed militia in the Bouba Ndjida National Park.18 Six years later, in 2018, six soldiers from Operation ‘Peace at Bouba Ndjida’ were assassinated. Following years of attempted incursions by poachers reported in the south of the park, at the border with Chad, a search operation was mounted by the commander of the 42nd LIU in the area where these poachers were reported on the night of 8 February 2018. The first group of BIR commandos were ambushed by the Sudanese poachers, resulting in the deaths of six soldiers, including Captain Liman, the commander of the 42nd LIU, and two civilians.19

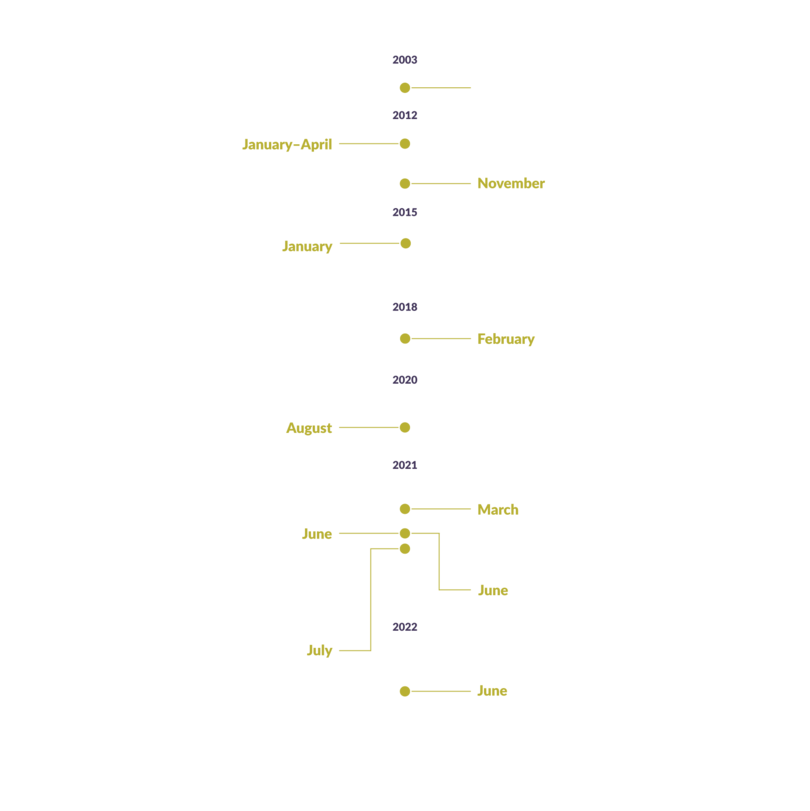

Incidents and events in the Bouba Ndjida National Park

Investigations following the elephant massacre in 2012, the 2018 BIR ambush, and several other incursions mostly by the Janjaweed for the purposes of killing elephants and other wildlife have revealed important information about the dynamics of the illicit activity and the modus operandi of the perpetrators involved.

According to the commander of Operation ‘Peace at Bouba Ndjida’, cross-border poaching activity in the Bouba Ndjida National Park is the work of a group of around 200 poachers operating in south-western Sudan and associated with the Janjaweed, who work in collaboration with certain Chadian rebel factions.20 They have a long tradition of hunting elephants and organize large-scale cross-border hunts every year during the dry season in almost all the countries of the Lake Chad basin. They usually operate in groups of 15 to 20 and are armed with AK-47s and axes. They are reportedly associated with powerful warlords in Sudan and allegedly have links to the Sudanese armed forces. They are said to operate in the park through alliances with local sheep herders, who act as guides.21

Members of rebel factions often use villages on the outskirts of Bouba Ndjida, such as Sinassi, Baikwa and Madingrin, as logistical bases from which to launch their poaching excursions. The armed poachers cross the border into Cameroon from neighbouring Chad or CAR, meet up with their guides in the surrounding villages and then break into the park. It is then inside the national park itself that the armed actors set up their camps, as the vastness of the area allows them to go unnoticed. According to one local resident, now in prison, who collaborated with the armed men:

They arrived in our village [of Madingrin] in the evening, at around 6 p.m., mounted on horses. They told us that they had come from Sudan looking for ivory tips, and wanted us to help them gain access to the park. They told us that they had a very large, established ivory trading network, as far away as China. If we helped them enter the park and kill the elephants, they would pay us hundreds of thousands of francs. And as an advance of the promised money, they gave us FCFA200 000 to share between us.22

The profits made by the illegal trade in animal products, primarily elephant ivory, have been used to purchase weapons and ammunition, as well as motorcycles and other vehicles, fuel, foodstuffs and salaries for the group combatants. The ivory from the various poaching campaigns is sold to Asian cartels and helps finance the activities of these criminal rebel groups.23 Poaching in the park has reportedly decreased over recent years, partly due to significant increases in surveillance and security of the park given its historical links to armed-group financing.24 One wildlife expert in Cameroon told the GI-TOC that the Bouba Ndjida National Park is now among the most secure in the country.25

Cameroon’s role in the illegal wildlife trade

Cameroon plays a major role as a source country for illegal wildlife products, assessed by the Global Organized Crime Index to have the joint-fifth most pervasive fauna-crimes market in Africa.26 The Bouba Ndjida park is not the only source: in December 2021, three suspected poachers were arrested for allegedly poaching elephants in Lobeke National Park, in eastern Cameroon, on the border with CAR.27 According to Francis Durand Nna, the highest government forestry and wildlife official in the country’s East region, the number of elephants killed illegally is likely to be underestimated by official figures, as patrolling areas regularly attacked by armed groups from CAR is increasingly difficult.28

Cameroon also operates as a key transit point for wildlife trafficking originating from other central African states, largely exported from Douala by sea, Yaoundé by air, or trafficked overland into Nigeria for export.29 The city of Garoua, approximately 170 kilometres north-west of the Bouba Ndjida National Park, is just one key transit point for illegal wildlife products coming from Chad and CAR (as well as from the park itself). Garoua has increased in importance following a shift in supply chains from the nearby city of Maroua, in light of escalating Boko Haram attacks in the latter.30 Stakeholders in Cameroon reported to the GI-TOC that law-enforcement vigilance is more lax in the north compared to the coastal routes, facilitating smuggling.31

Although wildlife crime is not among the illicit economies most heavily associated with conflict and instability – compared to arms trafficking, cattle rustling, kidnap for ransom and the illicit gold trade, for example32 – it is clear that in West and central Africa, the illicit trade in wildlife products has repeatedly been used as a source of financing for armed actors.

Operation ‘Peace at Bouba Ndjida’ and the reinforcement of the security forces in the national park’s neighbouring villages near the borders with Chad and the CAR, the main entry points for these poachers, have yielded significant successes in decreasing poaching in the park. Yet attempted forays into the park appear to persist. The complicity of local villagers in the illicit activities of the poachers illustrates the need for the government to engage local populations in any proposed responses. The enhanced military presence appears to have deterred the Janjaweed militias (who are reluctant to make the 1 400-kilometre journey from Sudan to then be foiled by the BIR). Although the true extent of armed group activity remains unknown, several incidents since 2021 have highlighted the potential for armed actors closer to home, in the form of the MLC emerging just across the border in Chad, to exploit Cameroon’s natural resources.

Soldiers from the Cameroonian bataillon d’intervention rapide on patrol in Bouba Ndjida National Park, March 2022.

Photo: Moussa Bobbo

Notes

-

Interview with commander of Operation ‘Peace at Bouba Ndjida’, Garoua, August 2022. ↩

-

Interview with security and criminality expert in northern Cameroon, 27 September 2022, by phone. See also Laurel Neme, Will mobilization of military forces stop elephant poaching in Cameroon? Save the Elephants, 15 February 2015, https://www.savetheelephants.org/about-elephants-2-3-2/elephant-news-post/?detail=will-mobilization-of-military-forces-stop-elephant-poaching-in-cameroon; Weekend Argus, Army to tackle poaching, 23 December 2012, https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/weekend-argus-sunday-edition/20121223/281784216421193. ↩

-

Interview with security and criminality expert in northern Cameroon, 27 September 2022, by phone. ↩

-

Email exchanges with three wildlife experts in Cameroon, September 2022. However, a security and crime expert based in Yaoundé told the GI-TOC that it is likely the MLC survive by means of illicit economies, and while it is difficult to know which ones exactly, it would be very surprising if elephant poaching were not one of them; Interview with security and crime expert in Yaoundé, 30 September 2022, by email. ↩

-

Hans De Marie, Twitter, 6 August 2020, https://twitter.com/hansdemarie/status/1291439281303695360?s=20&t=4nOgaaKsotw5WLOnxshJ5g. ↩

-

Interview with security and criminality expert in northern Cameroon, 27 September 2022, by phone. There is conflicting information available online, however. In December 2020, CAR authorities informed Cameroonian officials of ‘the creation, in the border region [of CAR and Cameroon], of an armed group called the Movement for the Liberation of Cameroon (MLC)’; see Cameroun24, Cameroun - Sécurité. Un Mouvement de Libération du Cameroun en gestation à frontière centrafricaine, https://www.cameroun24.net/actualite-cameroun-info-Un_Mouvement_de_Liberation_du_Cameroun_en_gestatio-56128.html. ↩

-

Cameroon Change Official, Facebook, 9 November 2021, https://fb.watch/fRxS88jKDz/. The video was originally posted by Cameroonian journalist Boris Bertolt, 1 March 2021; see Yannick A Kenne, Cameroun: Un mouvement rebelle hostile au régime de Yaoundé revendique une alliance présumée avec le ‘Mouvement 10 millions de Nordistes’, Cameroon-Info.Net, 1 March 2021, http://www.cameroon-info.net/article/cameroun-un-mouvement-rebelle-hostile-au-regime-de-yaounde-revendique-une-alliance-presumee-avec-le-395796.html. ↩

-

Christian Happi, Yaoundé imperturbable malgré la menace d’un groupe rebelle de renverser le régime Biya, Actu Cameroun, 6 April 2021, https://actucameroun.com/2021/04/06/yaounde-imperturbable-malgre-la-menace-dun-groupe-rebelle-de-renverser-le-regime-biya/. ↩

-

Lucia Bird and Lyes Tagziria, Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa, GI-TOC, September 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/west-africa-illicit-hub-mapping. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

See https://wea.globalinitiative.net/illicit-hub-mapping/map ↩

-

Interview with conservator of the Bouba Ndjida National Park, Bouba Ndjida National Park, April 2021. ↩

-

Interview with senior figure in the Chief Intelligence Unit of Operation ‘Peace at Bouba Ndjida’, Rey-Bouba, August 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with commander of Operation ‘Peace at Bouba Ndjida’, Garoua, July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with commander of Operation ‘Peace at Bouba Ndjida’, Rey-Bouba, February 2021, who reported on interview with arrested MLC member. ↩

-

Interview with conservator of the Bouba Ndjida National Park, Bouba Ndjida National Park, April 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with commander of Operation ‘Peace at Bouba Ndjida’, Garoua, July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with commander of Operation ‘Peace at Bouba Ndjida’, Rey-Bouba, February 2021. ↩

-

Interview with conservator of the Bouba Ndjida National Park, Bouba Ndjida National Park, April 2021. ↩

-

Interview with an individual arrested for collaborating with Sudanese poachers, Garoua Central Prison, March 2018. ↩

-

Interview with senior figure in the Chief Intelligence Unit of Operation ‘Peace at Bouba Ndjida’, Rey-Bouba, April 2020. ↩

-

Interview with security and criminality expert in northern Cameroon, 27 September 2022, by phone. ↩

-

Email exchange with wildlife expert at TRAFFIC, September 2022. ↩

-

GI-TOC, Global Organized Crime Index, September 2021, https://ocindex.net/rankings/fauna_crimes?f=rankings&view=Cards&group=Country&order=DESC&continent=africa&criminality-range=0%2C10&state-range=0%2C10. ↩

-

Moki Edwin Kindzeka, Cameroon deploys military to assist rangers as poaching increases, VOA News, 6 December 2021, https://www.voanews.com/a/cameroon-deploys-military-to-assist-rangers-as-poaching-increases/6341052.html. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

GI-TOC, Global Organized Crime Index: Cameroon country profile, September 2021, https://ocindex.net/country/cameroon. ↩

-

Lucia Bird and Lyes Tagziria, Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa, GI-TOC, September 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/west-africa-illicit-hub-mapping. Underscoring the importance of Garoua as a transit point for illicit wildlife commodities, in March 2021, 4 tonnes of pangolin scales, a significant proportion of which originated from the Democratic Republic of Congo and CAR, were seized. Pangolin scales are trafficked north and then across the border into Nigeria, before being trafficked back south and out through Nigeria’s ports. Interview with wildlife expert at TRAFFIC, August 2021, by phone. ↩

-

Lucia Bird and Lyes Tagziria, Organized crime and instability dynamics: Mapping illicit hubs in West Africa, GI-TOC, September 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/west-africa-illicit-hub-mapping. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩