The release from prison of drug traffickers convicted of coordinating Guinea-Bissau’s largest ever cocaine consignments seized by local authorities undermines any hopes of a brave new dawn in the country’s stance on drug trafficking offences

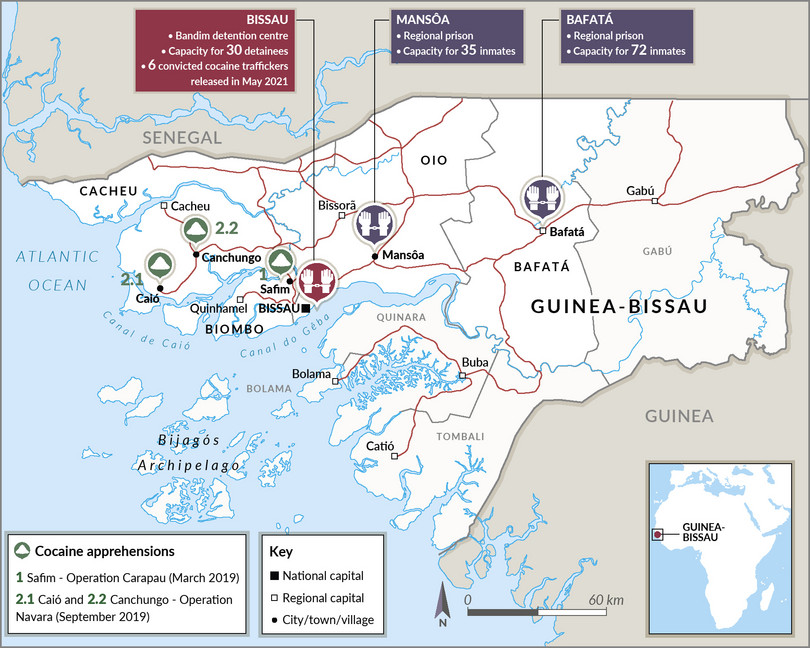

In March and September 2019, two major cocaine seizures – weighing in at 789 kilograms and 1 869 kilo-grams – were made in Guinea-Bissau, bringing the near-drought of significant cocaine seizures in West Africa since 2013 to an abrupt end. The seizures seemed to indicate that Guinea-Bissau’s institutions were adopting a hardened stance towards drug trafficking.1 And the fact that lengthy prison sentences were even handed down for those convicted (between 14 and 16 years for the ringleaders) was unprecedented for cocaine traffickers in Bissau, and was cited by INTERPOL as evidence of a newfound political will to finally tackle drug trafficking.2

But in May 2021, an investigation by the Judicial Police found that six of the individuals imprisoned on drug trafficking charges following the two bumper seizures in 2019 had been quietly released, allegedly with the collusion of elements of the state apparatus.3 The story of how the traffickers behind Bissau’s largest ever cocaine heists manoeuvred their way out of jail, albeit temporarily, is another instance of the corruption within the Guinea-Bissau criminal justice system and underscores how the briefly toughened measures against drug trafficking have eroded, with the focus switching to political considerations.

Figure 7 Guinea-Bissau, showing the locations of the 2019 cocaine seizures.

Crime and no punishment?

In March 2019, officials seized 789 kilograms of cocaine in the false bottom of a truck transporting fish that was en route to Mali from Bissau. The operation, dubbed ‘Carapau’, resulted in the conviction of three individuals, each receiving lengthy sentences.4 Shortly after, Operation Navara led to the September seizure of 1 869 kilograms of cocaine – the largest in the country’s history – and conviction of 12 individuals on 31 March 2020. The convictions and lengthy sentences broke with tradition in Bissau, where impunity is rife.

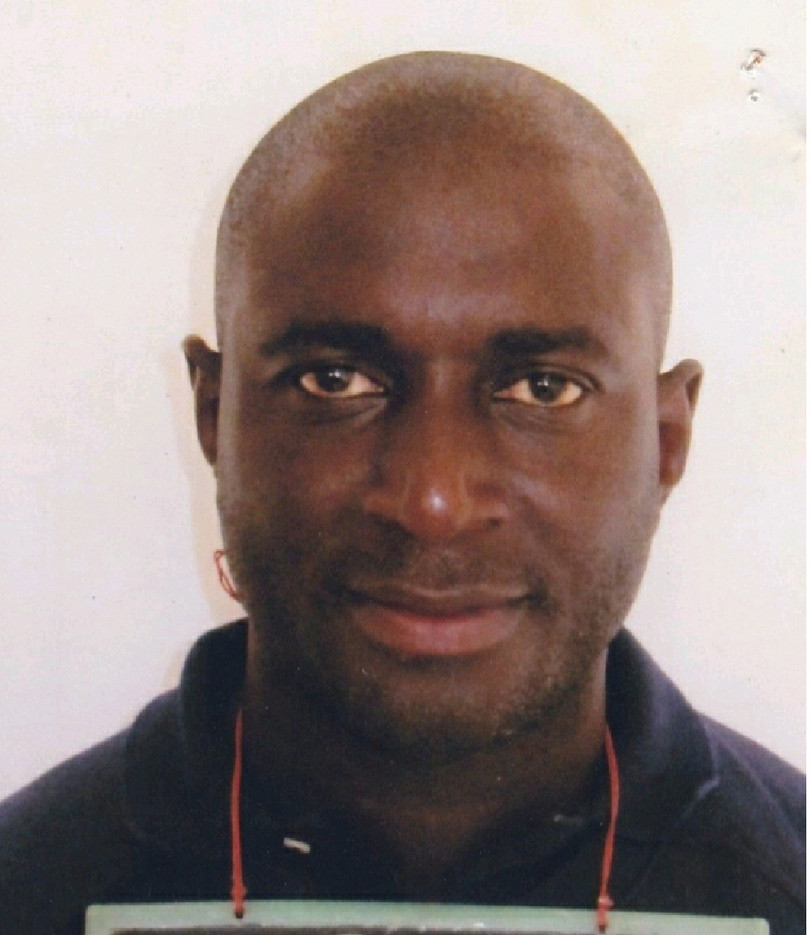

Braima Seidi Bá was sentenced in Guinea-Bissau’s Regional Court for his involvement in a cocaine trans-shipment to 16 years’ imprisonment, later commuted in the Appeal Court to six.

Photo supplied

Notably, however, the ringleaders of the network responsible for the September drug shipment – Braima Seidi Bá and Ricardo Monje – each sentenced to 16 years, were never detained. Bá, believed to be among the country’s most prominent drug traffickers, and the suspected mastermind of the March 2019 import, likely escaped arrest due to protection from elements of the Bissau-Guinean state infrastructure.5 One Bissau-Guinean businessman who regularly travels to Gambia reported that in mid-2021 Bá was residing in a hotel that he owns in Senegambia, a tourist beach half an hour from Banjul, the capital of Gambia.6 This businessman claimed that Bá is visible at the front desk of the hotel and at various restaurants in the area, suggesting that he believes his arrest, which would require coordination between Bissau-Guinean and Gambian law enforcement, to be extremely unlikely.7

This sense of impunity was reinforced in October 2020, when the sentences of those behind the September 2019 drug consignment were drastically diluted in a judgment handed down by the Court of Appeal.8 (Bá’s sentence, for example, was reduced from 16 years to six9). Former minister of justice Ruth Monteiro described the judgment as a ‘cloaked acquittal’,10 while local sources suspect that the determination was driven by bribes paid to the judges who handed down the majority judgment (Judge Aimadu Sauané issued a dissenting judgment, seen as a courageous stand against the majority).11 Abílio Có, president of the Drugs Observatory, a civil society organization seeking to collect data on drug use in Guinea-Bissau, criticized the judiciary’s decision to ‘lower the penalties’ and said that the successful investigations conducted by the Judicial Police were being undermined by corruption in the judiciary.12

Sick note

More troubling evidence emerged on 12 May 2021, when the Judicial Police received information that some of the prisoners convicted following operations Carapau and Navara had been released from Bandim Prison. The following day, it was confirmed that two of those convicted under Operation Carapau (Sidi Ahmed Mohamed and El Adji Marguei) and four convicted under Operation Navara (John Fredy Valencia Duque, Avito Domingos Vaz, Saido António Seidi Bá and Mussa Seidi Bá, the latter two being relatives of the ringleader, Braima Seidi Bá) had been released on medical grounds.13 While most of the prisoners had been released in April and May 2021, one individual, Saido António Seidi Bá, had been released in the first quarter of 2020.14

Suspecting wrongdoing, on 13 May the Judicial Police tracked down and once again detained the released prisoners, with the exception of one prisoner, who was not found. Statements given to the Judicial Police by each of the detained individuals apparently cited a number of different medical conditions that required urgent medical treatment and indefinite stays outside of prison. The prisoners claimed they were escorted out of the prison by prison officers, with some claiming they maintained contact with the head of the prison throughout their time outside the prison walls.

The head prison guard officer confirmed knowledge of the release of each prisoner and claimed that proper procedures had been followed, including judicial authorization for the treatment of the prisoners.15 Two doctors employed at two hospitals in which the prisoners had reportedly received treatment confirmed the medical conditions of each of the prisoners. Law enforcement officers reported that the vice president of the Supreme Court of Justice had authorized the temporary release of the prisoners.16

Those involved had taken extensive steps to cover their tracks, including using a scalpel to give one of the prisoners a scar to simulate the operation he reportedly received.

Subsequent Judicial Police investigations, however, found that the accounts given by the prisoners, prison staff and doctors were false and that the ailments had been fabricated. It was reportedly also discovered that those involved had taken extensive steps to cover their tracks, including using a scalpel to give one of the prisoners a scar to simulate the operation he reportedly received. On 24 May 2021, the Criminal Instruction Judge authorized the preliminary detention of the junior prison officials and doctors believed to have colluded in the prisoners’ release,17 but as of August 2021, officials and doctors were still at liberty as they awaited their trial, for which a date has not yet been set.18

Timeline of criminal justice processes of Operations Carapau and Navara

A return to blanket impunity for drug traffickers?

Guinea-Bissau has long operated as a platform for instability in the region, functioning as a safe haven for key illicit actors, as well as an important entry point for cocaine from South America.19 The circumstances around the release of those convicted of drug trafficking underscores how corruption in the criminal justice infrastructure in Guinea-Bissau undermines the work of elements of the Judicial Police and judiciary.

The Judicial Police investigation into the release of prisoners on alleged medical grounds indicates a degree of continuing focus on organized crime, at least by certain elements of the body. This is especially noteworthy given the growing politicization of the Judicial Police under President Umaro Sissoco Embaló, who came to power in early 2020 and whose focus is reportedly on weakening political opposition rather than investigating drug trafficking.20 According to sources in the Judicial Police interviewed by Bissau Digital in February 2021, the force has not conducted any investigations into drug trafficking since early 2020 and organized crime is no longer a strategic priority.21 Bissau-Guinean civil society organizations, including the Guinean Human Rights League, and media outlets have expressed concern about the growing use of the Judicial Police for political rather than criminal justice aims.22 The apparent lack of Bissau-Guinean state focus on responding to drug trafficking may be one factor behind the August 2021 designation of General Antonio Indjai, the leader of the 2012 coup and the target of previous US DEA sting investigations due to his involvement in drugs trafficking, as a new target under the US Government’s Narcotics Rewards Program. This designation, which offers a US$5 million reward for information leading to the arrest of Indjai, who has been on US, UN and EU sanctions lists since 2012, constitutes a unilateral step by the US in targeting key players in the Bissau-Guinean drugs market.23

These events indicate that the seizures and sentences of 2019–2020 did not mark the beginning of a strengthened response to drug trafficking, but rather a brief spell of independence in investigations by the Judicial Police. There have been no major seizures since – unlikely in itself a sign of diminished flows through the country, but rather a return to blanket impunity for drug traffickers.

Notes

-

Sidi Ahmed Mohamed, ringleader of the March seizure, was convicted on charges of drug trafficking in November 2019, together with two associates. Mohamed was sentenced to 15 years in prison and his associates to 14. UNODC, Guinea-Bissau: Drug smugglers receive record 16-year-jail sentences as justice system strengthened by UNODC, 10 April 2020, https://www.unodc.org/westandcentralafrica/en/2020-04-02-jugement-navara-guinee-bissau.html. ↩

-

For example, see INTERPOL, Guinea-Bissau: Triple prison conviction marks new era of anti-drug action with INTERPOL, 27 December 2019, https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2019/Guinea-Bissau-triple-prison-conviction-marks-new-era-of-anti-drug-action-with-INTERPOL; UNODC, Guinea-Bissau: Drug smugglers receive record 16-year-jail sentences as justice system strengthened by UNODC, 10 April 2020, https://www.unodc.org/westandcentralafrica/en/2020-04-02-jugement-navara-guinee-bissau.html. ↩

-

Information regarding this investigation was shared with the GI-TOC through case reports, together with a series of interviews with lawyers and law enforcement officers in Bissau between May and July 2021. ↩

-

UNODC, Bissau-Guinean authorities achieve largest ever drug seizure in the history of Guinea-Bissau, https://www.unodc.org/westandcentralafrica/en/2019-03-15-seizure-guinea-bissau.html. ↩

-

For example, during a brief stay in Bissau in March 2020, as the trial was ongoing, Bá was highly visible, clearly unafraid of arrest. Bá was hosted in the house of Danielson Francisco Gomes, director of Petroguin, a large public company. Mark Shaw and A Gomes, Breaking the vicious cycle: Cocaine politics in Guinea-Bissau, May 2020, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Guinea-Bissau_Policy-Brief_Final2.pdf. ↩

-

Interview, Bissau, May 2021. This was corroborated by two other sources based in Bissau with good knowledge of Seidi Ba’s movements in interviews, Bissau, June 2021. ↩

-

While there were reports of ongoing investigations in late 2020, these have not materialized to date. ↩

-

The Seidi Bá cocaine trial: A smokescreen for impunity?, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 20 January 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Guinea-Bissau-RB1.pdf. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with Ruth Monteiro, former minister of justice of Guinea Bissau, December 2020. ↩

-

The Seidi Bá cocaine trial: A smokescreen for impunity?, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, January 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Guinea-Bissau-RB1.pdf. ↩

-

Interview with Abílio Có, president of the Drugs Observatory, Bissau, December 2020. ↩

-

Notably, the relatives of Braima Seidi Bá were among those released. ↩

-

The sequence of events following the release of the prisoners outlined in this section is based on interviews with lawyers and law enforcement officers in Bissau between May and July 2021, and analysis of case reports. ↩

-

These statements were broadly corroborated by two other officials at Bandim prison. ↩

-

Interviews with law enforcement officers, Bissau, June 2021. ↩

-

Tribunal Regional de Bissau-Vara Crime, Juizo de Instrucao Criminal, Processo No 465/2021. ↩

-

Interview with members of judiciary and law enforcement, Bissau, 28 July 2021. ↩

-

For example, Banta Keïta, a Dakar resident who holds a French passport and is believed to be a key figure behind the January 2021 three-tonne seizure in Banjul, is reported to have fled to Guinea-Bissau, suspected to be under protection of the military. Drug Law enforcement Agency, the Gambia, Ministry of Interior, Information note on the seizure of 2ton, 952kg, 850g of cocaine, 8 January 2021; Ditadura do Consenso, Cocaína-3 Toneladas Apreendidas Na Gâmbia, 18 January 2021, http://ditaduraeconsenso.blogspot.com/2021/01/cocaina-3-toneladas-apreendidas-na.html; Atlanticactu, Gambie: Saisie de 3 tonnes de cocaïne, un enquêteur de la DLEAG écarté pour avoir interpellé un proche d’un chef d’état, 13 January 2021, https://atlanticactu.com/gambie-saisie-de-3-tonnes-de-cocaine-un-enqueteur-de-la-dleag-ecarte-pour-avoir-interpelle-un-proche-dun-chef-detat. Telephone interview with source in Guinea-Bissau, 20 January 2021. This is one of a number of examples; an additional illustration of Guinea-Bissau’s role as a ‘safe haven’ is that one of the three Senegalese men identified by local police to be behind the import of 4 kg of cocaine seized in dakar fled to Guinea-Bissau to avoid arrest. United Nations Security Council, report of the Secretary- General on the Activities of the united Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel, 24 december 2020, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/S_2020_1293_e.pdf. Benjamin roger, dakar cocaineseizure shows West African ports are easy transit hubs, The Africa report, 17 October 2019, https://www.theafricareport.com/18839/dakar-cocaine-seizure-shows-west-african-ports-are-easy-transit-hubs. ↩

-

The legally dubious closure of the Petroleum Regulation Agency by the Judicial Police at the behest of the president is cited as evidence of the politicization of the force by the Guinean Human Rights League. Interview, Bissau, 2 February 2021. On the deprioritization of drug trafficking, the president is reported to have repeatedly told the Judicial Police that drug trafficking is not a priority. Instead, he is reported to have ordered the Judicial Police to focus on political opposition and dissent. Interviews, Bissau, January 2021–July 2021. ↩

-

Guinean Judicial Police on the brink of explosion, Bissau Digital, 25 February 2021. ↩

-

Public statement made by the Guinean Human Rights League, 23 January 2021, http://www.lgdh.org. ↩

-

US Department of State, Antonio Indjai – New Target, 19 August 2021, https://www.state.gov/antonio-indjai-new-target. ↩