Northern Côte d’Ivoire: new jihadist threats, old criminal networks

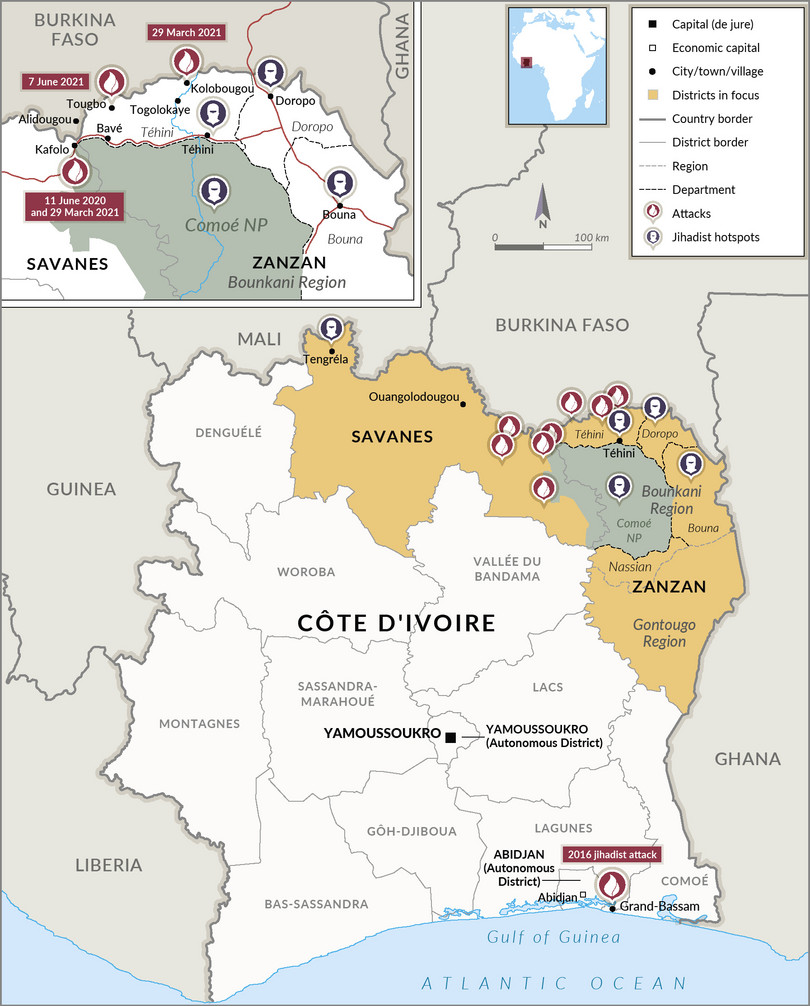

June 2020 marked the beginning of a spate of attacks by jihadist groups in the Bounkani region of Côte d’Ivoire, which borders Burkina Faso. At least 18 members of the Ivorian defence forces have been killed in attacks, including those in Kafolo on 11 June 2020 and 29 March 2021, in Kolobougou on 29 March 2021 and in Tougbo on 7 June 2021. The tactics and weaponry of violent extremist groups in Bounkani have also evolved, with groups beginning to use improvised explosive devices (IEDs). On 12 June 2021, three soldiers were killed when a military vehicle hit an IED on the road between Téhini and Togolokaye, near the border with Burkina Faso.1

These incidents illustrate the growing presence of violent extremism in northern Côte d’Ivoire and point to an apparent strategy by jihadist groups to expand their influence outside of their strongholds in landlocked Sahelian states such as Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger to coastal states in West Africa.2

Local law enforcement have attributed the increase in a range of criminal activities in the Bounkani region since 2017 to the growing presence of jihadist groups in the area and their increasing reliance on Ivorian revenue sources.3 However, while connections between jihadist actors and certain criminal economies, such as cattle rustling, have been ascertained, the extent to which the growth of criminal markets in the Bounkani region has been driven by jihadist actors remains unclear.

New actors access entrenched criminal economies

Northern Côte d’Ivoire has long been a significant zone of trafficking due to its porous borders with Mali and Burkina Faso.4 Criminal markets developed and matured with impunity over the course of a decade as civil war in the early 2000s diminished state control of the area. With Côte d’Ivoire de facto divided into north and south between 2002 and 2011, rebels in the north have profited from lucrative cross-border criminal activities.5 Triangular trafficking networks began moving fuel, wood, cannabis and other types of contraband between Mali, Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire, as well as gold from Côte d’Ivoire – where rebel commanders controlled specific mining sites – to Burkina Faso.

The partial return of Ivorian state authority in 2011 limited but did not stop trafficking activities in the far north of the country. Trafficking markets continued to flourish, and the southern border of Burkina Faso is currently known to be a lucrative zone for numerous trafficking activities, including arms, narcotics, gold, motorized vehicles and contraband cigarettes.6

The mix of patchy state control, borderland communities, who feel neglected in the country’s economic progress and flourishing criminal markets, presented an opportunity for jihadist groups in the cross-border region.7 Analysis of data collected by the Armed Violence and Conflict Location and Event Data Project points to a ‘jihadization of banditry’ in southern Burkina Faso in recent years, with a number of violent extremist groups, including Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), recruiting a range of armed actors involved in illicit markets.8 Ivorian law enforcement working in northern Côte d’Ivoire, and Lassina Diarra, author of a recent report on extremist dynamics in Northern Cote D’Ivoire, point to a similar evolution in the north of the country, particularly in Bounkani, with jihadist elements, predominantly from Mali and Burkina Faso, inserting themselves into local criminal economies to generate funding.9 However, many links between jihadist groups and illicit activities in the area are still tenuous or only just developing,10 and entrenched local criminal gangs have resisted jihadist attempts to encroach on their turf. Furthermore, there are important differences between criminal markets as to the extent of jihadi involvement.

Extent of the links between criminal and jihadist groups

The presence of jihadist groups in Côte d’Ivoire is believed to be concentrated in the Bounkani region, which is among the poorest in the country, with the towns of Bouna, Doropo and Téhini, close to the border with Burkina Faso, highlighted as particular hotspots. Jihadist movements and activities have also been reported in the Tengréla area, close to the Malian border, in Savanes district.11

Law enforcement officers in Bounkani link increases in three illicit markets – namely armed robberies of individuals and shops, armed highway robberies and kidnapping for ransom – to jihadist groups. It is key to exercise caution in making such linkages, as these illicit activities also take place in other regions, and the frequency of these acts can depend on a variety of factors, including economic hardship due to the COVID-19 pandemic and reduced capacity of local law enforcement.12

During research for this bulletin, Ivorian intelligence officers in Ouangolodougou, a town 30 kilometres from the Burkina Faso border, reported an increase in attacks on homes and shops in the Doropo and Bouna districts of Bounkani from late 2020,13 with at least 20 separate incidents occurring between October 2020 and March 2021. Intelligence officials in Abidjan believe these attacks have a dual purpose: to generate funds for the jihadist perpetrators – estimated amounts are as high as 14 million CFA (about 21 000 euros) – and to intimidate influential local figures who collaborate with the state defence forces.14

Figure 1 Sites of jihadist attacks in Côte d’Ivoire, 2016–2021.

The 2020 Kafolo attack and Hamza

On 11 June 2020, a group of militants attacked a joint military and police station in Kafolo, marking a clear escalation of violence in northern Côte d’Ivoire. While Ivorian authorities had long feared jihadist attacks in the area,15 the scale, sophistication and strategic focus of the attack – a night-time operation involving 30 men equipped with radios for communication – took authorities by surprise.16

A town near Kafolo, in northern Côte d’Ivoire, where the June 2020 attack occurred.

Photo: Issouf Sanogo/AFP via Getty Images

The attack – thought to be carried out by Katiba Macina militants affiliated with JNIM – killed 14 members of the Ivorian military and police, and was thought to be an act of retaliation for a joint Burkinabè-Ivorian operation of the previous month.17 That operation had targeted a jihadist group consisting of about 50 members led by Burkinabè Rasmane Dramane Sidibé, known by the alias of ‘Hamza’.18 Hamza is close to Malian Amadou Koufa, who leads Katiba Macina and reportedly sent Hamza to Côte d’Ivoire in 2019 to recruit and develop a local jihadist cell.19 The goal of Hamza’s efforts, local military officials say, is to create a sanctuary for jihadists along the Ivorian, Burkinabè and Malian borders, similar to the tri-border zone of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, where jihadist groups have made considerable inroads enmeshing themselves within local populations and economies.20

Since 2018 there has also been an increase in road blocks being used on certain routes in Bounkani to rob travellers by actors known as ‘coupeurs de route’ (‘road cutters’).21 Between 2018 and 2021, more than 20 incidents of armed robbery on roads were reported to law enforcement in the Bounkani region, mainly in the departments of Doropo, Bouna and Téhini.22 Investigations by intelligence officers in Côte d’Ivoire claim that these attacks were mainly organized by jihadists attempting to compensate for financing shortfalls due to a lack of financial aid from their affiliates abroad.23 Further evidence for this link came in the shape of testimony of victims of attacks in September 2020, who alleged that the perpetrators were armed with Kalashnikovs and emerged from Comoé National Park (where jihadist groups are known to shelter).24 However, some perpetrators, such as Kambiré Samuel, who was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment in 2019 for multiple counts of armed highway robbery on the road between Téhini and Bave in Bounkani region, have no reported links to jihadist groups.25

Law enforcement in Ouangolodougou also reported a rise in kidnappings since September 2020 in Doropo, Bouna and Téhini departments, with five cases of abductions detected between September 2020 and July 2021.26 All five kidnapping incidents targeted local traders, and are believed to have generated at least 45 million CFA (€68 500) in total.27 An intelligence service officer in Abidjan, the economic engine of the country, supports the allegations by regional law enforcement that the kidnappers are affiliated with jihadist groups.28

In northern Côte d’Ivoire more broadly, gold-mining sites have been targeted by jihadist groups, reflecting a trend also seen in neighbouring Mali and Burkina Faso.29 Since July 2021, jihadists have reportedly taken control of gold-mining sites in the triangle of Kologbo, Zepô and Hentira (Burkina Faso),30 and have increased activities around artisanal gold-mining in the villages of Togolokaye and Lorogbo (Téhini department).31 The gold extracted from these sites leverages purchasing networks based in Burkina Faso. According to one local gold buyer in Ouangolodougou, jihadist groups are not involved in extraction themselves, and the miners include both Ivorians and Burkinabè.32 Jihadists reportedly offer metal detectors to miners in exchange for cooperation.33

Ivorian investigations have also found links between the ringleader of a large network involved in cattle rustling activities … and regional jihadist figures.

Ivorian investigations have also found links between the ringleader of a large network involved in cattle rustling activities (among the most lucrative regional illicit economies) and regional jihadist figures.34 Until his arrest in 2019, the suspected ringleader, an ethnic Fulani from Burkina Faso known as ‘Hadou’, was based in Ouangolodougou, from where he allegedly coordinated a large cattle-rustling network operating in northern Côte d’Ivoire. Intelligence sources believe that, between 2017 and Hadou’s arrest in 2019, the network was behind the illegal trade of about 400 oxen and 200 sheep, generating about 60 million CFA (€91 400) in revenue.35 The stolen heads of cattle were sold to Ivorian butcheries, mainly for consumption in large cities such as Abidjan.

Hadou was reportedly in contact with individuals close to key regional jihadist figures such as Hamza (see above) and Hamza’s cousin, Ali Sidibé, known as ‘Sofiane’, who was arrested by Ivorian officials for his alleged coordination of the attack on Kafolo in June 2020.36 Although cattle rustling continues, it has not reached the scale or level of organization of the Hadou gang. Local testimonies still report links between cattle rustling activities and jihadist groups,37 but law enforcement officers in the region argue that these remain unproven.38

There are also concerns that jihadists may exploit the illegal wildlife trade. As mentioned above, a range of jihadist and criminal actors inhabit the Comoé National Park, a thick forest area of 1 million hectares in the north-east of Côte d’Ivoire, although recent military operations have prevented them from completely settling in the area.39 To date, there have been no reports that groups are exploiting the park’s natural resources, such as precious wood and endangered species, but one intelligence officer in Ouangolodougou reported that jihadists have promised local inhabitants that they could exploit these resources as soon as the jihadists chase away security forces.40 Similar developments have taken place in natural reserves across Burkina Faso41 and enable jihadist groups to woo communities by providing access to resources forbidden by the state, driving alternative governance arrangements. Jihadists have reportedly already targeted vulnerable elements of the community, particularly unemployed youth, for recruitment, offering cash and motorbikes as incentives.42

Easy to overstate, dangerous to underestimate

While jihadist activity in Côte d’Ivoire is often presented as a ‘foreign’ challenge by authorities,43 regional Ivorian intelligence repeatedly points to an escalation in jihadist groups leveraging domestic illicit economies as sources of revenue.44 Instead, these arguments should be carefully assessed: on the one hand, those who treat the threat as external may underestimate the involvement, and even integration, of jihadist groups in domestic illicit markets, whereas on the other, Ivorian authorities may have an interest in highlighting the jihadist threat in order to mobilize resources from foreign partners. Philippe Assale, an expert in violent extremism with over 15 years’ experience focussing on Cote D’Ivoire, warns against oversimplifying such links.45

Nuance is therefore important: while some jihadist groups in Côte d’Ivoire certainly appear to be drawing resources from domestic illicit markets, such links are easy to overstate and differ between markets. Furthermore, the balance between external and domestic financing for jihadist groups is unclear, and it should not be assumed that jihadist groups are exclusively funded by illicit activities in Côte d’Ivoire. Nevertheless, should jihadist groups be successful in establishing a steady revenue from these illicit markets, they may be able to sustain and potentially increase their capacity to launch sophisticated attacks, such as the one at Kafolo. The increasing involvement of jihadist actors in criminal networks could also bring heightened levels of violence to criminal activity, while their cohabitation with local communities could also drive extremist recruitment. As extremist actors and criminal networks increasingly operate in the same space, and seek to benefit from similar resources, distinctions between the two sets of actors are likely to become increasingly blurred, and the role of illicit economies in northern Côte d’Ivoire in resourcing extremist groups strengthened.

Notes

-

Military Chief of Staff Lassina Doumbia, statement, RTI, 13 June 2021, https://www.fratmat.info/article/213424/politique/bounkaniaxe-tehini-togolokaye-une-patrouille-de-larmee-objet-dune-attaque-complexe-bilan-03-morts-et-04-blesses-communique. ↩

-

Interview William Assanvo, researcher at the Institute for Security Studies, Abidjan, 15 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with Lassina Diarra, terrorism researcher, Abidjan, 1 July 2021; Lassina Diarra, Radicalisation et perception de la menace terroriste dans l’extrême-Nord de la Côte d’Ivoire, Timbuktu Institute, 7 June 2021, https://timbuktu-institute.org/index.php/toutes-l-actualites/item/468-rapport-inedit-radicalisation-et-perception-de-la-menace-terroriste-dans-l-extreme-nord-de-la-cote-d-ivoire; interview with intelligence service officer, Ouangolodougou, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Nord des pays du Golf de Guinée la nouvelle frontière des groupes jihadistes?, Promédiation et Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, April 2021, https://www.kas.de/fr/veranstaltungen/detail/-/content/nord-des-pays-du-golfe-de-guinee-la-nouvelle-frontiere-des-groupes-jihadistes. ↩

-

Interview with Hermann Crizoa, criminologist, Abidjan, 23 June 2021. ↩

-

Nord des pays du Golf de Guinée la nouvelle frontière des groupes jihadistes?, Promédiation et Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, April 2021, https://www.kas.de/fr/veranstaltungen/detail/-/content/nord-des-pays-du-golfe-de-guinee-la-nouvelle-frontiere-des-groupes-jihadistes. ↩

-

Lassina Diarra, Radicalisation et perception de la menace terroriste dans l’extrême-Nord de la Côte d’Ivoire, Timbuktu Institute, 7 June 2021, https://timbuktu-institute.org/index.php/toutes-l-actualites/item/468-rapport-inedit-radicalisation-et-perception-de-la-menace-terroriste-dans-l-extreme-nord-de-la-cote-d-ivoire. ↩

-

In light of the Kafolo attacks: the jihadi militant threat in the Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast borderlands, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, 24 August 2020, https://acleddata.com/2020/08/24/in-light-of-the-kafolo-attack-the-jihadi-militant-threat-in-the-burkina-faso-and-ivory-coast-borderlands/. ↩

-

Lassina Diarra, Radicalisation et perception de la menace terroriste dans l’extrême-Nord de la Côte d’Ivoire, Timbuktu Institute, 7 June 2021, https://timbuktu-institute.org/index.php/toutes-l-actualites/item/468-rapport-inedit-radicalisation-et-perception-de-la-menace-terroriste-dans-l-extreme-nord-de-la-cote-d-ivoire; interview with law enforcement officer, Ouangolodougou, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with Philippe Assale, violent extremism researcher, Abidjan, 13 July 2021. ↩

-

Nord des pays du Golf de Guinée la nouvelle frontière des groupes jihadistes ?, Promédiation et Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, April 2021, https://www.kas.de/fr/veranstaltungen/detail/-/content/nord-des-pays-du-golfe-de-guinee-la-nouvelle-frontiere-des-groupes-jihadistes. ↩

-

Interview with Philippe Assale, violent extremism researcher, Abidjan, 13 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with intelligence service officer, Ouangolodougou, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with intelligence service officer, Abidjan, 28 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with Arthur Banga, military researcher, Abidjan, 21 June 2021. ↩

-

Vincent Duhem, Terrorisme: l’attaque de Kafolo, un tournant pour la Côte d’Ivoire?, Jeune Afrique, 15 June 2020, https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1000865/politique/terrorisme-lattaque-de-kafolo-un-tournant-pour-la-cote-divoire/. ↩

-

Interview with army official, Abidjan, 14 July 2021. ↩

-

Cyril Bensimon, La menace djihadiste s’enracine en Côte d’Ivoire, Le Monde, 7 July 2021, https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2021/07/07/en-cote-d-ivoire-une-menace-djihadiste-qui-s-enracine_6087398_3212.html; In light of the Kafolo attacks: the jihadi militant threat in the Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast borderlands, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, 24 August 2020, https://acleddata.com/2020/08/24/in-light-of-the-kafolo-attack-the-jihadi-militant-threat-in-the-burkina-faso-and-ivory-coast-borderlands/. ↩

-

Burkina Faso-Côte d’Ivoire: les secrets de l’opération antiterroriste « Comoé », Jeune Afrique, 10 June 2020, https://www.jeuneafrique.com/998211/politique/burkina-faso-cote-divoire-les-secrets-de-loperation-antiterroriste/. ↩

-

Interview with army official, Abidjan, 14 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with law enforcement officer, Ouangolodougou, 23 July 2021; Justin Coulibaly, Côte d’ivoire: le roi de Nassian braqué par des coupeurs de route, des Microbes?, Afrik.com, 14 July 2020, https://www.afrik.com/cote-d-ivoire-le-roi-de-nassian-braque-par-des-coupeurs-de-route-des-microbes. While Ivorian authorities report an overall decrease in ‘coupeurs de route’ between 2019 and 2020, this was not reported by law enforcement in the Bounkani region. See Baisse du phénomène des coupeurs de route en Côte d’Ivoire, APA News, 4 February 2021, http://apanews.net/fr/news/reduction-du-phenomene-des-coupeurs-de-route-en-cote-divoire-etat-major. ↩

-

Interview with law enforcement officer, Ouangolodougou, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

12 coupeurs de route routed by the gendarmerie on the Koutouba-Mango axis (Bounkani), Ivorian Press Agency, 27 September 2020, https://www.aipci.net/cote-divoire-aip-12-coupeurs-de-route-mis-en-deroute-par-la-gendarmerie-sur-laxe-koutouba-mango-bounkani. ↩

-

Un coupeur de route condamné à 10 ans de prison ferme à Bouna, News Abidjan, 14 August 2019, https://news.abidjan.net/articles/661847/titre?redirect=true. ↩

-

Interview with intelligence service officer, Ouangolodougou, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Three of the hostages each paid 5 million CFA (€7 618) for their release. A fourth paid 20 million CFA (€30 473). The fifth and final hostage paid 10 million CFA (€15 236). Interview with intelligence service officer, Ouangolodougou, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with intelligence service officer, Abidjan, 28 July 2021. ↩

-

William Assanvo, Baba Dakono, Lori-Anne Théroux-Bénoni and Ibrahim Maïga, Extrémisme violent, criminalité organisée et conflits locaux dans le Liptako-Gourma, Institut D’études de Sécurité, 10 December 2019, https://issafrica.org/fr/recherches/rapport-sur-lafrique-de-louest/extremisme-violent-criminalite-organisee-et-conflits-locaux-dans-le-liptako-gourma. ↩

-

Interview with intelligence service officer, Ouangolodougou, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with a gold buyer, Ouangolodougou, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

How jihadist groups extract revenue from these sites – be it providing security, taxation or through direct involvement in sales – as well as the revenues they may be generating remains unclear and not well defined. Lassina Diarra, Radicalisation et perception de la menace terroriste dans l’extrême-Nord de la Côte d’Ivoire, Timbuktu Institute, 7 June 2021, https://timbuktu-institute.org/index.php/toutes-l-actualites/item/468-rapport-inedit-radicalisation-et-perception-de-la-menace-terroriste-dans-l-extreme-nord-de-la-cote-d-ivoire; William Assanvo, Baba Dakono, Lori-Anne Théroux-Bénoni and Ibrahim Maïga, Extrémisme violent, criminalité organisée et conflits locaux dans le Liptako-Gourma, Institut d’études de sécurité, 10 December 2019, https://issafrica.org/fr/recherches/rapport-sur-lafrique-de-louest/extremisme-violent-criminalite-organisee-et-conflits-locaux-dans-le-liptako-gourma. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with intelligence service officer, Ouangolodougou, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. After being arrested in June 2020, Sofiane reportedly acknowledged his connection with Amadou Koufa, founder of Katiba Macina. Vincent Duhem, Côte d’Ivoire: comment les jihadistes tentent de s’implanter dans le nord, Jeune Afrique, 20 May 2021, https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1174346/politique/cote-divoire-comment-les-jihadistes-tentent-de-simplanter-dans-le-nord. ↩

-

Nord des pays du Golf de Guinée la nouvelle frontière des groupes jihadistes?, Promédiation et Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, April 2021, https://www.kas.de/fr/veranstaltungen/detail/-/content/nord-des-pays-du-golfe-de-guinee-la-nouvelle-frontiere-des-groupes-jihadistes. ↩

-

Interview with intelligence service officer, Ouangolodougou, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with army official, Abidjan, 14 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with law enforcement officer, Ouangolodougou, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Henry Wilkins and Danielle Paquette, Burkina Faso’s wildlife reserves have become a battle zone, overrun by militants and poachers, The Washington Post, 13 September 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/burkina-fasos-wildlife-reserves-have-become-a-battle-zone-overrun-by-militants-and-poachers/2020/09/12/dae444bc-f1c0-11ea-9279-45d6bdfe145f_story.html. ↩

-

Vincent Duhem, Côte d’Ivoire: comment les jihadistes tentent de s’implanter dans le nord, Jeune Afrique, 20 May 2021, https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1174346/politique/cote-divoire-comment-les-jihadistes-tentent-de-simplanter-dans-le-nord. ↩

-

William Assanvo, Le terrorisme en Côte d’Ivoire ne relève plus seulement d’une menace extérieure, Institut D’études de Sécurité, 15 June 2021, https://issafrica.org/fr/iss-today/le-terrorisme-en-cote-divoire-ne-releve-plus-seulement-dune-menace-exterieure. ↩

-

Interview with law enforcement officer, Ouangolodougou, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with Philippe Assale, violent extremism researcher, Abidjan, 13 July 2021. ↩