Criminal economies are a key factor in Burkina Faso’s Solhan massacre

In the early hours of 5 June 2021, armed attackers arrived at an informal gold-mining site near the village of Solhan, Burkina Faso, and proceeded to murder 132 civilians according to official figures, though local sources reported at least 160.1

One survivor, ‘Alassane’, whose name has been changed, awoke to the sound of gunfire at around 2 a.m. As others dived into the narrow mine shafts, he tried to hide in a house, but the attackers soon discovered him and shot him twice at point blank range. One bullet went through his arm and he lost a testicle as the other travelled through both legs. He survived by playing dead.2

The massacre is Burkina Faso’s worst terrorist attack since 2015, when the latest cycle of jihadist violence began. Since that time, Burkina Faso’s state forces and government-backed militias, known as Volunteers for the Defence of the Homeland (VDP), have been battling against various armed group actors, some linked to JNIM, which is affiliated with al-Qaeda, and against ISGS. Other actors, including bandits and criminal gangs, operate within this milieu, often in conjunction with VDPs and jihadist groups. Citizens have reportedly often been targeted by VDPs, jihadist groups and even state security forces.3

Troublingly, the Solhan massacre is also the first confirmed major case of child soldiers being used in Burkina Faso’s conflict. Alassane says his attackers were young teenagers, around the age of 15,4 and the GI-TOC has spoken to four witnesses who all corroborate that child soldiers constituted the majority of the assailants.5 A statement by Burkina Faso’s Minister of Communication, Ousenni Tamboura, also confirmed that most of the combatants who carried out the attack in Solhan were children.6 This appears to reflect a larger trend, with the number of child soldiers detected in Burkina Faso having grown considerably in 2021.7

At the time this bulletin was being prepared, it was not possible to verify where or how the children were recruited, but one member of the VDP in Yagha province, where Solhan is located, said the child soldiers had been drawn from the local area.8 Women were also confirmed by witnesses to be among the Solhan attackers,9 with a VDP member and a local expert on extremist groups telling the GI-TOC that in some cases, children and women join extremist groups along with a household patriarch and participate in fighting as well.10

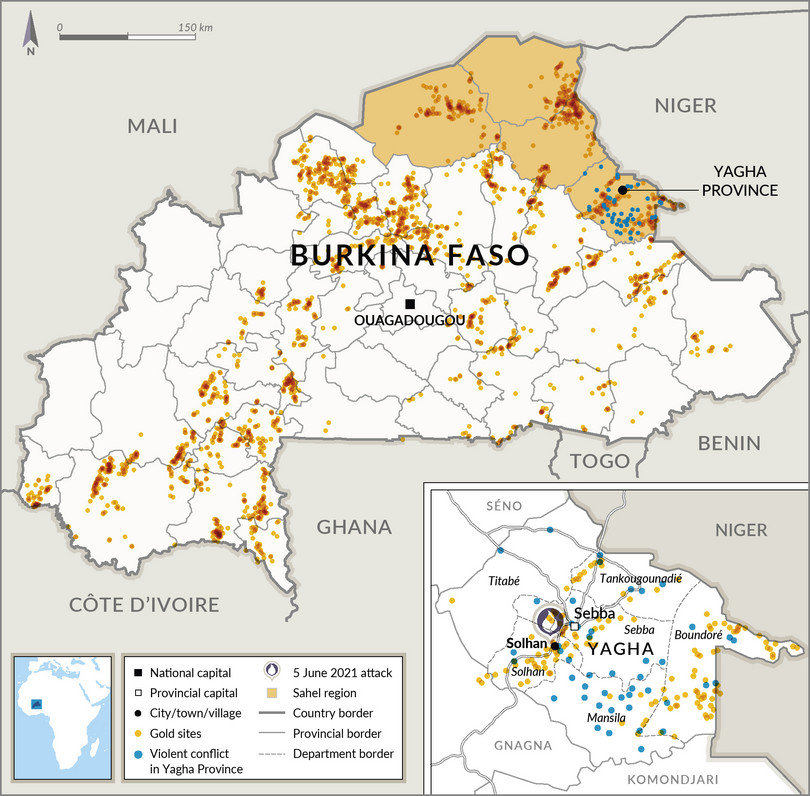

Figure 2 Site of the Solhan attack, areas of violent conflict in Yagha Province and gold mines across Burkina Faso.

Source: L’Agence Nationale d’Encadrement des Exploitations Minières Artisanales et Semi-mécanisés (ANEEMAS)

At the time of writing, it was unclear which armed group was responsible for the massacre. Locals rarely distinguish between ISGS and JNIM on the ground, and affiliations are often murky. Available evidence indicates that a group loosely affiliated with JNIM carried out the attack.11 The fact that JNIM released a statement denying responsibility for and condemning the attack12 could be an attempt to maintain JNIM’s image as a more moderate extremist group compared to ISGS.13

There are competing theories as to the motive behind the attack. Multiple commentators on Burkina Faso’s conflict, including Human Rights Watch, have said the Solhan massacre was an act of jihadist vengeance for VDP recruitment at the mine,14 but the reality is more complex and tied to criminal economies in the province.15

Key non state armed groups in Burkina Faso

JNIM (Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin)

Official branch of al-Qaeda in the region and the result of a 2017 merger between Ansar Dine, the Front de Libération du Macina, al-Mourabitoun, and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). Although the group only formed in 2017, JNIM’s antecedents, AQIM and al-Mourabitoun, claimed responsibility for the January 2016 attacks at the Cappuccino restaurant and Splendid Hotel in Ouagadougou, killing 30 and temporarily holding more than 170 people hostage.

ISGS (Islamic State in the Greater Sahara)

Regional Islamic State affiliate that emerged after a split within the Mouvement pour l’Unicité et le Jihad en Afrique de l’Ouest. The group pledged allegiance to ISIS in 2015 and was officially recognized by the Islamic State in 2016. ISGS has claimed responsibility for a spate of attacks in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. In addition to targeting state security forces, international troops present in the region and civilian populations who refuse to collaborate, ISGS also began targeting rival JNIM fighters in Burkina Faso in 2020.

VDP (Volunteers for the Defence of the Homeland)

Created by the Burkinabè government by law in January 2020, the Volunteers for the Defence of the Homeland, known by their French acronym VDP, were initially made up of self-proclaimed self-defence militias such as the Kogleweogo. Volunteers receive two weeks of training from state security services, and in some cases are provided automatic weapons. VDPs have been accused of multiple human rights violations, as documented by several human rights organizations.

Criminal economies in Yagha province

The relationship between armed groups and criminal networks is complicated and varied. Extremist groups sometimes run protection rackets, while bandits with no ideological motivations regularly join extremist groups to carry out criminal activities, and also enjoy the support of larger criminal networks.16 According to Ousseni Nacanabo, a representative of an artisanal mining association in Yagha, ‘there are three types among the jihadists: armed robbers, those who just want money and are ready to do anything and those who really believe in the jihadist purpose’.17 Siaka Coulibaly, an analyst with the Center for Public Policy Monitoring by Citizens in Burkina Faso, estimates that the percentage of fighters in Burkina Faso’s armed groups who could be regarded as genuine ideological jihadists could be as low as 15%.18

All the conflict actors in Yagha – JNIM, ISGS and the VDPs – generate income from criminal activities. According to Héni Nsaibia, a senior researcher at the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), the main criminal economic activities in Yagha province are ‘illegal mining, cattle theft and fuel smuggling, as well as smuggling and trading in other goods and contraband.’19

Fuel smuggling is common across West Africa, with much of the smuggled fuel coming into Burkina Faso from bordering coastal countries, such as Ghana and Togo. In Yagha, extremist groups extract money from criminals in exchange for the safe passage of fuel through the province. But it is artisanal gold mines that are thought to be the largest source of income for extremist groups in Yagha, and by some margin. Armed groups extract zakat (tax) from the miners or simply rob them for cash or gold. Armed group members are also known to work the mines themselves to extract gold. This also provides them with the ability to blend in with the local civilian population, while mines are convenient places to hide weapons and give jihadists ready access to explosives that can be repurposed for IEDs.

While the size of these criminal economies in Yagha is unclear, armed groups have largely succeeded in tapping into them in order to procure food, small arms, motorcycles (the mode of transport favoured by extremist groups in the Sahel) and fuel. Analysts note, however, that these dynamics are by no means fixed, with control of the criminal economies constantly shifting between the groups. Competition over control of these economies is likely to have played a central role in recent clashes between JNIM and ISGS in Yagha province, according to local security experts and diplomatic sources.20 Nsaibia estimates that there are around 500–600 armed jihadist group members in Yagha province.21

View of an artisanal gold mine in the centre-north region of Burkina Faso and a mine shaft opening, 17 February 2020.

Photo: Henry Wilkins

‘We’ve recently noticed that there is a financial shortage among criminal organizations. Finance is drying out, leading some terrorists to assault school canteens to get food’

This heightened competition may be driven by a period of scarcity of resources among armed groups. ‘We’ve recently noticed that there is a financial shortage among criminal organizations. Finance is drying out, leading some terrorists to assault school canteens to get food,’ said Jacob Yaredebatioula, an expert on extremist groups at Ouagadougou University.22 One of the reasons jihadist groups are opening up new fronts in Burkina Faso, such as in the vicinity of the southern city of Banfora, and on the border with Côte d’Ivoire, Yaredebatioula explained, is because they are going through ‘hard times in terms of finance’.23

Mass displacement caused by the conflict has also had a negative impact on gold mining and other economic activities in Yagha province, resulting in fewer citizens and diminished economic activity from which violent extremist groups can extract zakat.24 Government measures and extremist attacks have also damaged local livelihoods, increasing unemployment rates and consequently the pool of individuals vulnerable to recruitment by armed groups.

Battle over a gold mine

In this context of straitened finances, the role of Solhan as one of the most profitable gold mines in the province made it a vital node in the battle between the VDPs and extremist groups – and may have driven the massacre. Nacanabo, the representative from the artisanal mining association, estimates that gold mines in Yagha could potentially yield 2 billion CFA (approximately €3 million) in revenue per year.25

Yaredebatioula suggests that the VDPs were able to secure the area of Solhan and mining sites, undermining the extremist groups’ criminal activities. ‘I think this is one of the reasons that VDPs and their families were directly targeted.’26 Siaka Coulibaly, from the aformentioned Center for Public Policy Monitoring by Citizens, also believes the massacre was an attempt by extremist groups to gain control of the mine for profit.27

A newspaper vendor in Ouagadougou sells a local newspaper headlining the story of the Solhan massacre of 5 June 2021.

Photo: Olympia de Maismont/AFP via Getty Images

In the aftermath of Solhan, the government has closed all artisanal gold mines in Yagha province, further underscoring the extent to which local authorities believe gold-mining represents a key revenue stream for violent extremism in the region. According to Nacanabo, mining in Yagha has largely ceased, although some small-scale mining is still going on illegally.28 But such moves are likely to only displace the battle for criminal resources elsewhere, and as conflict spreads, the criminal economy is likely to expand in sync.

Notes

-

France 24, At least 160 killed in deadliest attack in Burkina Faso since 2015, France 24, 5 June 2021, https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20210605-dozens-of-civilians-killed-in-attack-on-northern-burkina-faso-village. ↩

-

Interview with ‘Alassane’, 26 July 2021. ↩

-

Burkina Faso: Residents’ accounts point to mass executions, Human Rights Watch, 8 July 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/07/08/burkina-faso-residents-accounts-point-mass-executions. ↩

-

Interview with ‘Alassane’, 26 July 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with various witnesses of the Solhan attack, 29 June 2021. ↩

-

Henry Wilkins and Danielle Paquette, Child soldiers carried out attack that killed at least 138 people in Burkina Faso, officials say, The Washington Post, 24 June 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/06/24/burkina-faso-child-soldiers. ↩

-

Sam Mednick, Burkina Faso sees more child soldiers as jihadi attacks rise, Associated Press, 1 August 2021, https://apnews.com/article/africa-united-nations-child-soldiers-burkina-faso-e28058b0ae92dfa44df9633bc6affcef. ↩

-

Phone interview with VDP member (name withheld) from Sebba, 27 July 2021. ↩

-

‘Alassane’ said that one of his attackers was a woman. A hawker who hid on the roof of a building throughout the attack says he saw women and children among the attackers. ↩

-

Phone interview with VDP member (name withheld) from Sebba, 22 July 2021; interview with Jacob Yaredebatioula, expert on extremist groups at Ouagadougou University, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Massacre de Solhan: entre le GSIM et l’EI, l’enjeu de la reputation, Radio France Internationale, 25 June 2021, https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20210625-massacre-de-solhan-entre-le-gsim-et-l-ei-l-enjeu-de-la-r%C3%A9putation; Henry Wilkins, Solhan massacre exposes failure to tackle Sahel crisis, Al Jazeera, 10 June 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/6/10/solhan-massacre-exposes-failure-tackle-sahel-crisis-burkina-faso. ↩

-

See, for example, this statement released by JNIM: @Menastream, #BurkinaFaso: In a statement diffused locally in #Mali, #JNIM denies responsibility and condemns the massacre in Solhan, #Yagha Province, Twitter, https://twitter.com/MENASTREAM/status/1402242166840303616. ↩

-

Daniel Ezenga and Wendy Williams, The puzzle of JNIM and militant Islamist groups in the Sahel, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 1 December 2020. The government of Burkina Faso meanwhile has attributed the attack to a new group, separate to JNIM and ISGS, called ‘Mouhadine. Some analysts are sceptical as to whether this group actually exists, while the name appears to be an approximation of the ‘mujahadeen’, a generic term to describe jihadist fighters anywhere in the world. See Fatma Bendhaou, Burkina Faso: Two suspects arrested in connection with the investigation into the Solhan attack, Anadolu Agency, 29 June 2021, https://www.aa.com.tr/fr/afrique/burkina-faso-deux-suspects-arr%C3%AAt%C3%A9s-dans-le-cadre-de-lenqu%C3%AAte-sur-lattaque-de-solhan/2288293. ↩

-

Corinne Dufka, Armed islamists’ latest Sahel massacre targets Burkina Faso, Human Rights Watch, 8 June 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/06/08/armed-islamists-latest-sahel-massacre-targets-burkina-faso. ↩

-

Interview with Jacob Yaredebatioula, expert on extremist groups at Ouagadougou University, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Marlboro’s Man: Philip Morris’s representative in Burkina Faso is a known cigarette smuggler, Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, 26 February 2021, https://www.occrp.org/en/loosetobacco/marlboros-man-philip-morris-representative-in-burkina-faso-is-a-known-cigarette-smuggler. ↩

-

Interview with Ousseni Nacanabo, representative of artisanal mining association, Burkina Faso, 24 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with Siaka Coulibaly, Siaka Coulibaly, an analyst with the Center for Public Policy Monitoring by Citizens, 21 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with Héni Nsaibia, senior researcher at the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project and Menastream, a private security consultancy, 31 July 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with Western diplomat and local security experts in Ouagadougou, June/July 2021. See also, Sahel 2021: Communal wars, broken ceasefires, and shifting frontlines, Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, https://acleddata.com/2021/06/17/sahel-2021-communal-wars-broken-ceasefires-and-shifting-frontlines. ↩

-

Interview with Héni Nsaibia, senior researcher at the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project and Menastream, a private security consultancy, 31 July 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with Doctor Jacob Yaredebatioula, expert on extremist groups at Ouagadougou University, 23 July. ↩

-

The displacement caused by the conflict in Burkina Faso has reached 1.3 million nationwide. ↩

-

Interview with Ousseni Nacanabo, representative of artisanal mining association, Burkina Faso, 24 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with Jacob Yaredebatioula, expert on extremist groups at Ouagadougou University, 23 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with Siaka Coulibaly, Burkinabè analyst and activist, 2 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with Ousseni Nacanabo, artisanal mining association, Burkina Faso, 24 July 2021. ↩