Russia’s military, mercenary and criminal interests in West Africa grew in 2022 and look set to expand in 2023.

The fallout of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has had major consequences for Russia’s engagement around the world in 2022. West Africa is no exception. Russia has sought to increase its political involvement in Africa since the 2014 invasion of Crimea.1 But as Russia has become more economically and politically isolated under the increasing weight of Western sanctions, the importance of Africa as a strategically significant region for Russia to engage in, both to facilitate business opportunities (to shore up its ailing domestic economy) and to court political allies, has escalated.

At the same time, Western sanctions – which prevent targeted entities from accessing much of the global banking system and globalized supply chains – have had a disruptive effect on the business interests of Russian oligarchs in West Africa.2 For example, Russian gold producer Nordgold – which has been placed under sanctions along with its former major shareholder, oligarch Alexey Mordashov – has had to find new routes to export gold from its mines in Guinea and Burkina Faso (where it recently received a new mining licence),3 reportedly via Dubai.4

Illicit economies (and the ambiguous legal ‘grey zones’ through which criminal actors and sanctioned entities seek to publicly present themselves as legitimate) also play a significant part in this geopolitical wrangling. As described in the March 2022 issue of this bulletin, sanctioned Russian entities in Africa – which are primarily concentrated in the mining sector – may be turning to illicit means of transporting goods, minerals and money to fly under the radar of international sanctions.5

The mercenary organization Wagner Group often appears to work as a proxy for the Russian state in Africa, seeking to pursue Russian state interests and disrupt Western influence on the continent.6 In late January 2023, the US government took the unusual step of designating Wagner as a ‘transnational criminal organization’ – a move that signals a new approach in defining and levying sanctions on Wagner and its enablers. The group is reportedly involved in illicit economies, such as industrial-scale smuggling of natural resources (particularly gold), which enables it, and probably indirectly the Russian state, to evade sanctions.7 These activities are more fully documented in an upcoming in-depth report by the GI‑TOC, ‘The grey zone: Russia’s military, mercenary and criminal engagement in Africa’.

But the Wagner Group is also responsible for grotesque violence against civilians in several African countries. In Mali, for example, Wagner troops were reportedly involved in a joint operation with the Malian armed forces in January 2022, in which an elderly woman was burned to death inside her home after a soldier began looting and setting buildings on fire.8 So while Wagner involvement in illicit economies is important in and of itself, the group’s entrenchment in African countries – primarily authoritarian regimes – facilitated by its illicit activities, simply extends its window of opportunity to carry out apparent human rights abuses against civilians.

Wagner Group – entrenching its role in illicit economies?

Controlled by a close ally of Vladimir Putin, Yevgeny Prigozhin, the Wagner Group appears to offer a package of services designed to appeal to autocratic leaders: mercenary troops who can help ensure territorial control; and political strategists who can manipulate and shape public debate using social media and, at times, disinformation.9 In return, as various reported examples show, Wagner seeks commercial gain, not just in cash but in access to natural resources, particularly in mining, which it exploits through a complex network of linked companies.

The group has expanded rapidly across Africa following its first documented military engagement on the continent, when around 500 troops were deployed to Sudan in late 2017.10 In 2022, Wagner troops were deployed in the Central African Republic (CAR), Mali, Libya and Sudan. Meanwhile, Wagner’s political influence operations have been active in several other African countries.

Figure 1 Timeline of Wagner Group presence in Africa.

Note: Indicative dates only

Source: GI-TOC

Wagner has been accused of using whatever means necessary – including criminal activity on a vast scale – to achieve its apparent aims of commercial gain and furthering Russian influence.11 International NGOs, independent and UN experts and the media have all levelled accusations at the group: from the indiscriminate use of violence against civilians in its military engagements to disinformation campaigns and election-rigging, to industrial-scale smuggling of natural resources.12

For example, Wagner’s gold mining operations in Sudan and its proximity to the country’s military leaders are being used to carry out gold smuggling on an extensive scale.13 This has allegedly intensified since the start of the war with Ukraine, to bolster Russia’s gold reserves and counter Western sanctions.14

Central African Republic – diluting presence but retaining influence

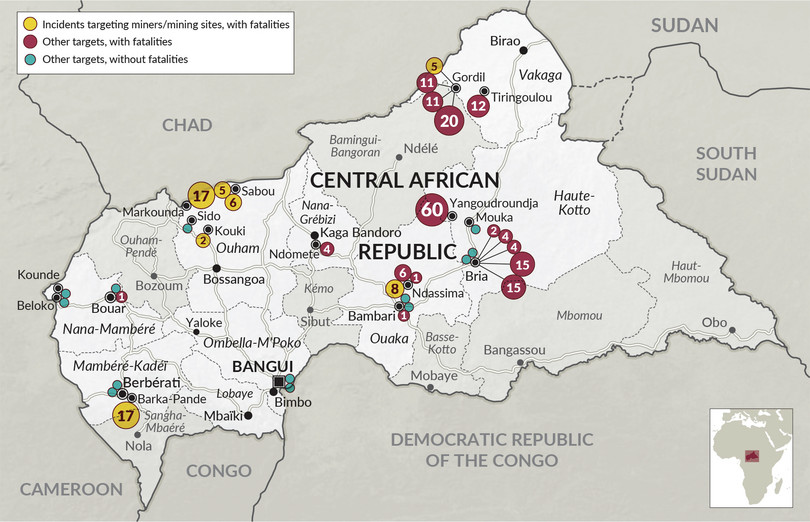

CAR is the most well-developed example of the Wagner business model in Africa. Wagner has provided President Faustin-Archange Touadéra with military and political strategy support. This has proven pivotal in sustaining Touadéra’s embattled presidency against an onslaught of rebel groups and has led to Wagner taking a leading role in CAR’s security apparatus. Clashes between Wagner personnel and rebel groups continued into 2022. In March 2022, at least seven people were killed after Wagner troops were ambushed by militants from the Popular Front for the Rebirth of Central African Republic rebel group.15 Two months earlier, the Russians had allegedly been responsible for the massacre of more than 30 civilians in what was purportedly a targeted operation against the Union for Peace rebel group.16 The mercenaries have, in fact, been accused of the killing and torture of civilians on several occasions.17

Figure 2 Wagner violence against civilians in the Central African Republic, 2022.

Source: ACLED

In exchange for their services, the Wagner Group appears to have developed a large footprint in CAR’s economy, with access to natural resources, such as gold, diamonds and timber. Wagner-linked companies have been granted access to natural resources by the CAR government, often expropriating existing rights granted to other companies.

Gold miners at Ndassima gold mine, 40 kilometres from Bambari, in the eastern part of the Central African Republic.

Photo: Thierry Bresilion/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Outside of the mining concessions that Wagner has been able to gain control over, the group has also been accused of looting and smuggling diamonds and gold. In Lobaye, as far back as 2019, Wagner has reportedly been covertly buying diamonds from local collectors.18 The group has also allegedly purchased gold and diamonds directly from rebel groups.19 Elsewhere in the country, Wagner troops have attacked artisanal mining communities and confiscated diamonds and gold.20 For example, they were recently accused of taking over a local diamond sector in a conflict-affected area of CAR by force, via a diamond company the group is alleged to control.21

In the first half of 2022 alone, Wagner reportedly carried out attacks on mines in at least six different locations in CAR – attacks that appear to be ‘more like raids for plunder’, as opposed to strategic attempts to secure and extract resources in the medium to short term.22 Furthermore, there have been reports of Russian nationals manning customs points, including at the border entering Garoua-Boulaï in Cameroon, a key transit point which plays an important role in gold flows, allegedly with the consent of the CAR government.23

In light of stretched resources resulting from military needs in Ukraine, Wagner is seemingly seeking to extract rents from as many informal and illicit economies as possible. According to a UN source, the group is reportedly looking to exploit the annual cattle migration into CAR from neighbouring Cameroon and Chad, which takes place each year between November and April. Armed groups are known to draw substantial resources from this, either by engaging in cattle theft directly or by providing protection to herders.24

Mali – the latest theatre for Wagner’s operations

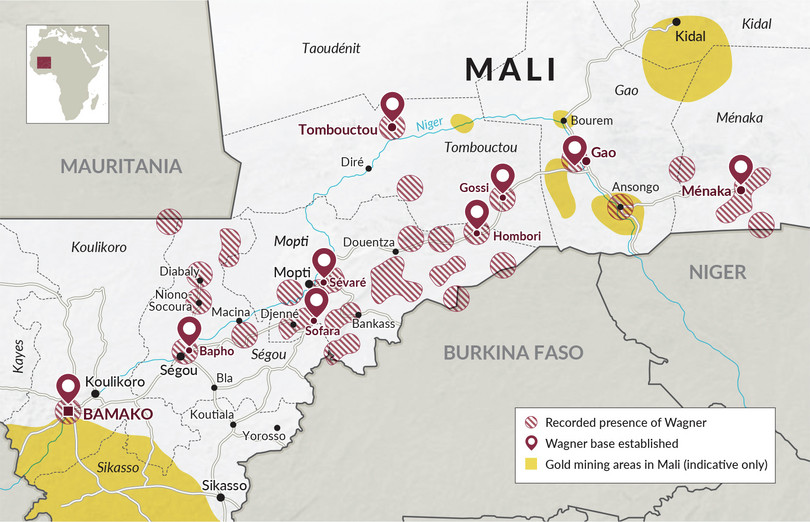

Since the first Wagner troops arrived in Bamako in November 2021, at least 1 000 Wagner officers have been deployed in Mali, primarily across the central regions but also further afield.25 The relationship between the Malian military and France, Mali’s former main international partner, worsened to the extent that Paris put an end to Operation Barkhane, its counterterrorism mission in Mali in mid-August 2022.26 Russia has been sowing anti-French and pro-Russian sentiment in Mali for over five years, cultivated via a sophisticated use of soft power and social media.27 But the end of Operation Barkhane opened a window of opportunity for even greater Russian military engagement in Mali.28

Figure 3 Wagner Group areas of operation in Mali.

Source: GI-TOC, ACLED and MENASTREAM, adapted from Jules Duhamel, Areas of operation – Wagner Group (Mali), 24 July 2022, https://julesduhamel.wordpress.com/2022/07/24/areas-of-operation-wagner-group-mali-2.

The Wagner Group do not carry out operations alone, instead carrying out patrols alongside the Malian armed forces and self-defence militias. Since their arrival in Mali, the Russian mercenaries have been repeatedly implicated in operations that have targeted and killed civilians. In March 2022, several hundred civilians were killed in the village of Moura in an attack allegedly involving the Wagner Group; in October, the group was once again accused of a civilian massacre in the same central region of Mopti.29 Islamist armed groups across the Sahel regularly exploit intercommunal tensions and grievances against the government, and the fact that the victims of the latest massacre in which the Russian mercenaries are implicated all belonged to the Fulani community is likely to simply exacerbate such grievances.30 As JNIM continues its recruitment approach of winning ‘hearts and minds’, Wagner activity has simply ‘created more fertile ground for such outreach efforts’.31

Wagner may have Mali’s gold mining sector in its sights. Obtaining payment through mining concessions is part of a clear Wagner playbook adopted by the group across a range of its engagements in Africa; were similar strategies to be underway in Mali, it is likely that such entry points are already being exploited.32 A lack of public information on how Wagner has been paid by Mali’s junta has spurred speculation that Wagner may be given access to mining concessions in the future, as an alternative form of payment. While some media investigations have claimed that Wagner has established gold mining companies in Mali,33 our research has not been able to independently verify these claims. It remains to be seen in future whether, as international observers expect, Wagner will develop the same mechanisms for exploiting mining resources and smuggling in Mali as they have in Sudan and CAR.34

Where will Wagner go in 2023?

As the war in Ukraine has not turned into the quick victory that Putin expected, some Wagner troops have been withdrawn from deployment in Africa to redirect forces towards Ukraine.35 Unofficial estimates from local observers, UN and diplomatic staff in CAR, for example, suggest that the number of Wagner troops in the country has more than halved.36 However, the vulnerability of the CAR government to rebel forces means that the mercenaries remain a powerful influence in CAR’s security apparatus. In addition, the situation in Ukraine has not prevented Wagner from deploying troops in new environments such as Mali.

In fact, some evidence suggests that Wagner may be aiming to expand into new territories. In Burkina Faso, events surrounding coups in January and September 2022 have fuelled Western fears that Wagner will begin operating there. Following the January coup, another Russian private military company – the Officers Union for International Security (COSI)37 – publicly offered the new Burkinabé government Russian military ‘instructors’. COSI represents the Russian military ‘instructors’ in CAR.38

The question of whether Burkina Faso would align itself with France (its former colonial power) or with Russia became a central part of the country’s political turmoil. In their announcement of the September coup on state TV, the latest coup leaders declared their wish to seek ‘other [international] partners ready to help us in our fight against terrorism’.39 In late January 2023, a spokesman for the Burkinabé government announced that they were giving all French special forces soldiers one month to depart the country.40 This came shortly after French authorities announced they had received a letter demanding the depature of its ambassador to Burkina Faso.41

The latest coup saw hundreds of protestors in Ouagadougou waving Russian flags, attacking a French embassy and cultural centre,42 and holding Russian flags atop UN armoured vehicles.43 This was an escalation of other pro-Russia protests seen in the wake of the January coup and the months since.

Prigozhin made several supportive statements following both coups.44 The September coup could, according to certain analysts, mark the first instance of Russia directly instigating a coup, rather than simply capitalizing on it.45 Others, however, strongly disagree. According to a Burkinabé security analyst, for example, claims of Russian involvement in initiating the coup in September are ‘completely false – the coup was the direct result of [former interim president] Damiba’s leadership, who was more interested in playing politics and restoring the old regime’.46 Moreover, Burkina Faso’s Minister of Foreign affairs has recently denied any link between the government and Wagner, arguing that state soldiers and members of the Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland, a self-defence armed group, are ‘the Wagner of Burkina Faso’,47 in a statement appearing to suggest they have no intention of seeking the support of Wagner troops.

While most focus has been on Burkina Faso, increasingly close military ties between Russia and other countries in the region, such as Cameroon, with whom Russia signed a military deal in April 2022, have also raised concerns among Western players.48 It is not just international actors showing concern about possible Wagner involvement in the region. The president of Ghana publicly alleged that Burkina Faso had already entered into an agreement with the mercenaries, offering them a mine in exchange for their services – claims that, however, are not supported by any evidence thus far and has been denied by the Burkinabé authorities.49

Nevertheless, given the resources required to finance and man the ongoing war in Ukraine, and significant investment in Mali, Wagner may be spread too thin to expand operations into new territories, such as Burkina Faso, even if invited to do so. Reports of Wagner recruiting from prisons in Russia since mid-2022 highlight the extent of their stretched human resources.50 Where Wagner will source their manpower will therefore be an important question going forward.

From a strategic point of view, we can also expect Wagner to deepen its economic footprint in West Africa and CAR in 2023, particularly in high-value sectors such as gold and diamonds. As Russia continues to be economically isolated by sanctions, maintaining flows of gold into Russia – obtained through Prigozhin’s network of companies or smuggled by Wagner troops – secures an economic lifeline.51 At the same time, Russian presence in several West African countries continues to contribute, indirectly and in some cases directly, to growing instability across the region.

This article draws on research from an upcoming GI-TOC report entitled ‘The grey zone: Russia’s military, mercenary and criminal engagement in Africa’, written with the support of the Hanns Seidel Foundation. If you would like to receive the full report when it is published, please sign up here.

Notes

-

Paul Stronski, Late to the party: Russia’s return to Africa, Carnegie Endowment, October 2019, https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/10/16/late-to-party-russia-s-return-to-africa-pub-80056. ↩

-

Marcena Hunter, Going for gold: Russia, sanctions and illicit gold trade, GI-TOC, April 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/russia-sanctions-illicit-gold-trade. ↩

-

Le Burkina Faso accorde à une compagnie russe le permis d’exploitation d’une nouvelle mine d’or, Le Monde, 8 December 2022, https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2022/12/08/le-burkina-faso-accorde-a-une-compagnie-russe-le-permis-d-exploitation-d-une-nouvelle-mine-d-or_6153527_3212.html. ↩

-

Nordgold gets creative to refine its African gold in the Emirates, Africa Intelligence, 23 September 2022; Nordgold’s golden airlift from Dinguiraye to Dubai, Africa Intelligence, 7 October 2022. Dubai is home to other Russian-owned gold mining companies with interests in Africa, such as Emiral Resources, which has interests in Ghana, Sudan and Mauritania; see: https://emiral.com. Africa Intelligence claims that Emiral Resources is assisting Nordgold in its new export routes (but we have not independently confirmed this). ↩

-

Observatory of Illicit Economies in West Africa, Re-examining Russia’s presence in West Africa’s gold sector, Risk Bulletin – Issue 3, GI-TOC, March 2022, https://riskbulletins.globalinitiative.net/wea-obs-003/01-russias-presence-in-west-africas-gold-sector.html. ↩

-

See, for example, Bellingcat, Putin chef’s kisses of death: Russia’s shadow army’s state-run structure exposed, 14 August 2020, https://www.bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2020/08/14/pmc-structure-exposed; Jason Burke and Luke Harding, Leaked documents reveal Russian effort to exert influence in Africa, The Guardian, 11 June 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/11/leaked-documents-reveal-russian-effort-to-exert-influence-in-africa. ↩

-

See, for example, Nima Elbagir et al., Russia is plundering gold in Sudan to boost Putin’s war effort in Ukraine, CNN, 29 July 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/07/29/africa/sudan-russia-gold-investigation-cmd-intl/index.html. ↩

-

Catrina Doxsee and Jared Thompson, Massacres, executions, and falsified graves: The Wagner Group’s mounting humanitarian cost in Mali, Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/massacres-executions-and-falsified-graves-wagner-groups-mounting-humanitarian-cost-mali. ↩

-

See, for example, Russia’s Madagascar election gamble, BBC News Africa, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6wH64iztZM0. ↩

-

Vanda Felbab and Steven Pifer, Russia’s Wagner Group in Africa: Influence, commercial concessions, rights violations, and counterinsurgency failure, Brookings, 8 February 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2022/02/08/russias-wagner-group-in-africa-influence-commercial-concessions-rights-violations-and-counterinsurgency-failure/. ↩

-

Russia is plundering gold in Sudan to boost Putin’s war effort in Ukraine, CNN, 29 July 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/07/29/africa/sudan-russia-gold-investigation-cmd-intl/index.html. See also UN Human Rights Office, CAR: Experts alarmed by government’s use of ‘Russian trainers’, close contacts with UN peacekeepers, Press release, 31 March 2021, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2021/03/car-experts-alarmed-governments-use-russian-trainers-close-contacts-un?LangID=E&NewsID=26961. ↩

-

See, for example, Human Rights Watch, Central African Republic: Abuses by Russia-linked forces, May 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/05/03/central-african-republic-abuses-russia-linked-forces. See also, Catrina Doxsee and Jared Thompson, Massacres, executions, and falsified graves: The Wagner Group’s mounting humanitarian cost in Mali, Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/massacres-executions-and-falsified-graves-wagner-groups-mounting-humanitarian-cost-mali. ↩

-

Russia is plundering gold in Sudan to boost Putin’s war effort in Ukraine, CNN, 29 July 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/07/29/africa/sudan-russia-gold-investigation-cmd-intl/index.html. ↩

-

Tom Collins, How Putin prepared for sanctions with tonnes of African gold, The Telegraph, 3 March 2022, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/terror-and-security/putin-prepared-sanctions-tonnes-african-gold. ↩

-

The Signal Room, Russian contractors ambushed in Mbomou prefecture, Incident Briefings, 8 March 2022. ↩

-

UN probing alleged killings by CAR forces, Russia mercenaries, Al Jazeera, 22 January 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/22/un-probing-alleged-killings-by-car-forces-russia-paramilitaries. ↩

-

Human Rights Watch, Central African Republic: Abuses by Russia-linked forces, 3 May 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/05/03/central-african-republic-abuses-russia-linked-forces. ↩

-

Interview with local businessman, Bangui, 2019. ↩

-

The Sentry, State of prey: Proxies, predators, and profiteers in the Central African Republic, October 2020, https://thesentry.org/reports/state-of-prey. Wagner have reportedly engaged in business with a former warlord/diamond smuggler named Abdoulaye Hissène; for his profile, read The Sentry, Fear, inc.: War profiteering in the Central African Republic and the bloody rise of Abdoulaye Hissène, November 2018, https://thesentry.org/reports/fear-inc. ↩

-

Les mercenaires Wagner en Centrafrique: des diamants et des exactions, La Croix, https://www.la-croix.com/Monde/mercenaires-Wagner-Centrafrique-diamants-exactions-2022-02-27-1201202388; Racket et vol, la gaffe des mercenaires de Wagner à Kouki traumatise la population, Corbeau News, 11 September 2022, https://corbeaunews-centrafrique.org/racket-et-vol-la-gaffe-des-mercenaires-de-wagner-a-kouki-traumatise-la-population. ↩

-

Josef Skrdlik, Report: Wagner mercenaries profit from Central Africa’s blood diamonds, OCCRP, 7 December 2022, https://www.occrp.org/en/daily/17129-report-wagner-mercenaries-profit-from-central-africa-s-blood-diamonds. ↩

-

Jason Burke and Zeinab Mohammed Salih, Russian mercenaries accused of deadly attacks on mines on Sudan-CAR border, The Guardian, 21 June 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jun/21/russian-mercenaries-accused-of-deadly-attacks-on-mines-on-sudan-car-border. ↩

-

Input at a Chatham House rules event from a specialist on Russia’s influence in CAR, June 2022. ↩

-

Interview with UN personnel, Paris, September 2022. ↩

-

Map of Wagner operations in Mali as of 15 July 2022 shared by geospatial analyst Jules Dechamel, Twitter, 24 July 2022, https://twitter.com/julesdhl/status/1551287276667273218/photo/1. ↩

-

Ministère des armées, Opération Barkhane, https://www.defense.gouv.fr/operations/operations/operation-barkhane. ↩

-

Peter Apps, With arms and Facebook, Russia is entrenched in Mali, The Arab Weekly, 23 April 2022, https://thearabweekly.com/arms-and-facebook-russia-entrenched-mali. ↩

-

It is also worth noting that this ability of Russia to fill the security void left by France is built on a longstanding military partnership between Russia and Mali, as more than 80% of the country’s armaments are of Russian origin. See Le Mali reçoit quatre hélicoptères et des armes de la Russie, France 24, 1 October 2021, https://www.france24.com/fr/afrique/20211001-le-mali-re%C3%A7oit-quatre-h%C3%A9licopt%C3%A8res-et-des-armes-de-la-russie. ↩

-

Paul Lorgerie, Mali massacre survivors say white mercenaries involved in killings, Reuters, 14 April 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/mali-massacre-survivors-say-white-mercenaries-involved-killings-2022-04-14. ↩

-

Jason Burke, Russian mercenaries accused of civilian massacre in Mali, The Guardian, 1 November 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/nov/01/russian-mercenaries-accused-of-civilian-massacre-in-mali. ↩

-

Wassim Nasr, How the Wagner Group is aggravating the jihadi threat in the Sahel, CTC Sentinel, 15, 11, 2022, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/how-the-wagner-group-is-aggravating-the-jihadi-threat-in-the-sahel, p 25. ↩

-

Raphael Parens, The Wagner Group’s playbook in Africa: Mali, Foreign Policy Research Institute, March 2022, https://www.fpri.org/article/2022/03/the-wagner-groups-playbook-in-africa-mali. ↩

-

Benjamin Roger and Mathieu Olivier, Wagner au Mali : enquête exclusive sur les mercenaires de Poutine, Jeune Afrique, 18 February 2022, https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1314123/politique/wagner-au-mali-enquete-exclusive-sur-les-mercenaires-de-poutine. See also Pierre-Elie de Rohan Chabot and Christophe Le Bec, Western companies brace for a hit as Bamako launches gold mining audit, Africa Intelligence, 9 November 2022, https://www.africaintelligence.com/west-africa/2022/11/09/western-companies-brace-for-a-hit-as-bamako-launches-gold-mining-audit,109843135-eve. ↩

-

In CAR, for example, troops that are alleged to be linked to Wagner are reported to have seized control of mines whose concessions formally belong to others – in this case, Chinese companies. See Chief Bisong Etahoben, Chinese and Russians clash at mining sites in Central African Republic, HumAngle, 1 May 2021, https://humanglemedia.com/chinese-and-russians-clash-at-mining-sites-in-central-african-republic. ↩

-

Cyril Bensimon, Russia’s involvement in the Central African Republic disrupted by the war in Ukraine, Le Monde, 31 March 2022, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2022/03/31/russia-s-involvement-in-the-central-african-republic-disrupted-by-the-war-in-ukraine_5979446_4.html; Russia reduces number of Syrian and Wagner troops in Libya, Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/88ab3d20-8a10-4ae2-a4c5-122acd6a8067. ↩

-

Remote interviews with local observers, UN and diplomatic staff, Bangui, August 2022. ↩

-

As it is often referred to in public reporting following the French translation of the name, Communauté des Officiers pour la Sécurité Internationale; see https://officersunion.org/ru. ↩

-

Communauté des Officiers pour la Sécurité Internationale; see https://officersunion.org/ru. ↩

-

Danouma Ismael Traore, Twitter, 1 October 2022, https://twitter.com/Danoumis_Traore/status/1576223589208330240?s=20&t=9_Ga-gp1Hkztz3sisRHMlQ. ↩

-

Burkina Faso confirms it has ended French military accord, Al Jazeera, 23 January 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/1/23/burkina-faso-ends-french-military-accord-says-will-defend-itself. ↩

-

Burkina Faso’s military junta asks France to recall ambassador, France24, 3 January 2023, https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20230103-burkina-faso-s-military-regime-orders-french-ambassador-to-leave. ↩

-

Jason Burke, Burkina Faso coup fuels fears of growing Russian mercenary presence in Sahel, The Guardian, 3 October 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/03/burkina-faso-coup-fears-growing-russian-mercenary-presence-sahel-north-africa. ↩

-

Henry Wilkins, Twitter, 6 October 2022, https://twitter.com/Henry_Wilkins/status/1578096714744930305?s=20&t=NUVV2eO4OBFOqJrZ9rAMnA. ↩

-

Most recently, in September, Prigozhin described coup leader Ibrahim Traoré as ‘a truly worthy and courageous son of his motherland’, and noted that the people of Burkina Faso were throwing off the yoke of colonialism. See Кепка Пригожина, Telegram, 1 October 2022, https://t.me/Prigozhin_hat/1736. ↩

-

Sam Mednick, Russian role in Burkina Faso crisis comes under scrutiny, AP News, 18 October 2022, https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-africa-france-west-a6384d7134e8688c367a68721f657857. ↩

-

Interview with a Burkinabé security analyst, December 2022, by phone. ↩

-

‘Nos soldats et nos VDP sont le Wagner du Burkina’ (Ministre), APA News, 24 January 2023, http://www.apanews.net/mobile/uneInterieure.php?id=4969125. ↩

-

Cameroon signs agreement with Russia in further boost to military ties, RFI, 22 April 2022, https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20220422-cameroon-signs-agreement-with-russia-in-further-boost-to-military-ties-wagner-ukraine. ↩

-

Interview with a Burkinabé security analyst, December 2022, by phone. See also Burkina-Russie: Aucune mine n’a été cédée à Wagner, assure le ministre des mines, Simon-Pierre Boussim, LeFaso.net, 20 December 2022, http://lefaso.net/spip.php?article118282, and Lalla Sy, Wagner Group: Burkina Faso anger over Russian mercenary link, BBC News, 16 December 2022, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-63998458. ↩

-

Pjotr Sauer, ‘We thieves and killers are now fighting Russia’s war’: How Moscow recruits from its prisons, The Guardian, 20 September 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/sep/20/russia-recruits-inmates-ukraine-war-wagner-prigozhin. ↩

-

Marcena Hunter, Going for gold: Russia, sanctions and illicit gold trade, GI-TOC, April 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/russia-sanctions-illicit-gold-trade. ↩