Re-examining Russia’s presence in West Africa’s gold sector.

With the Russian invasion of Ukraine resulting in a tsunami of economic sanctions, Russia’s presence in the West Africa gold sector has taken on new meaning. Sanctions regimes and their bite are only expected to increase, raising questions about how Moscow and other targeted entities will generate funds, move money internationally, and access foreign currencies going forward. Gold is likely to be part of the answer, as a commodity easily moved around the world outside of financial networks and with a strong overlap existing between licit and illicit flows.

Russia has been building its influence in Africa since 2014, including with the governments of West African gold producers Mali and the Central African Republic (CAR).1 Interlinkages range from the presence of Russian private military companies (PMCs) and gold mines majority-owned by Russian entities, to warm relations between Moscow and West African host governments. Although not a new phenomenon, an increasing number of gold-mining companies with Russian links are becoming active in Africa’s industrial-mining sector.2 However, Russian interests can at times be difficult to identify. These relationships raise the possibility that Moscow and other sanctioned actors will continue gold-mining operations or may funnel gold with Russian origins through West Africa.

While not inherently illicit, these activities become illegal when gold is smuggled or laundered into gold markets that have barred transactions with Moscow or other sanctioned entities. The explicit exclusion of Russian refineries by the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA),3 and calls by US lawmakers for sanctions on Russian gold transactions, reflect the growing blockades that sanctioned actors will face in accessing international gold and financial markets.4 Additionally, Russian gold miner Nordgold, which has operations in Burkina Faso and Guinea,5 is majority-owned by Alexey Mordashov. Mordashov, who is reportedly Russia’s wealthiest man, is now a target of EU sanctions.

Criminal networks have the potential to play a pivotal role in enabling Moscow and other sanctioned entities to use gold, including that mined in West Africa, by disguising the origins and ownership of gold, as well as the financial beneficiaries of gold transactions, to lessen the impact of sanctions.

Insecurity creates opportunity for Russian interests

Insecurity across areas of Africa has created demand for Russian PMCs as well as opportunities for Russians to build relationships with, and gain access to valuable mineral reserves in, countries where Russian PMCs are operating.6 In West Africa, the Wagner Group, one such Russian PMC, is reported to be currently active in CAR and Mali.

The Wagner Group has been deployed in CAR ever since President Faustin-Archange Touadéra’s visited Russia in 2017. Touadéra allegedly accepted an offer of military support, weapons and training from Russia, prompting some analysts to report concerns that Russia may be attempting to gain access to CAR’s minerals sector.7 Two Russian diamond and gold companies in CAR linked to the Wagner Group have been sanctioned by the US. These include the Russia-based M Finans, a precious-metals mining company and provider of private security services, and the CAR-based gold- and diamond-mining company Lobaye Invest SARLU.8 Following Touadéra’s 2017 trip to Russia, the CAR government granted mining licences to Lobaye Invest SARLU, which the UN says is ‘interconnected’ with the Wagner Group.9 More recently, the UN Panel of Experts reported that observers have noted that CAR’s armed forces and Russian offensives are concentrated in key mining centers and mineral-rich areas, fuelling suspicion that CAR is primarily interested in securing the country’s diamond and gold wealth, which the Russians are seeking to capitalize on.10

Yet, analysts have observed that assessing the extent of the Russians’ role in the minerals sector to date is difficult. While some state that Russian mining activities are sporadic and only amount to acquiring ‘pocket money’, others have noted that the activities are intense and systemic.

In November 2021, the Wagner Group reportedly entered Mali following a request by Bamako for private military support, although Mali has denied using Wagner Group mercenaries.11 According to the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), visits to Bamako by Wagner executives, as well as Russian geologists who are known for their association with the PMC, suggests that Wagner personnel may also eventually provide site security services to Russian companies engaged in mining activity. This would be consistent with alleged Wagner activity in and agreements with other African states.12 Furthermore, with ECOWAS sanctions against Mali still in place, Bamako may find it difficult to generate the cash necessary to pay for PMC services. Security analysts have speculated that the Malian military may look to the gold sector to generate vital revenues in this regard.13

The presence of Russian PMCs in CAR and Mali and warm relations with the governments present an opportunity for Russia to continue to financially benefit from gold-mining operations and evade sanctions by laundering gold through transit and destination markets.

Gold mining in Mali

The Malian gold sector has developed rapidly over the past two decades. The rise in production and favourable tax policies, which attracted gold imports from its West African neighbours,14 has led to a boom in gold exports. Mali is the third-largest gold producer in Africa, with industrial production reaching 63.4 tonnes in 2021,15 valued at over US$4 billion at current gold prices.

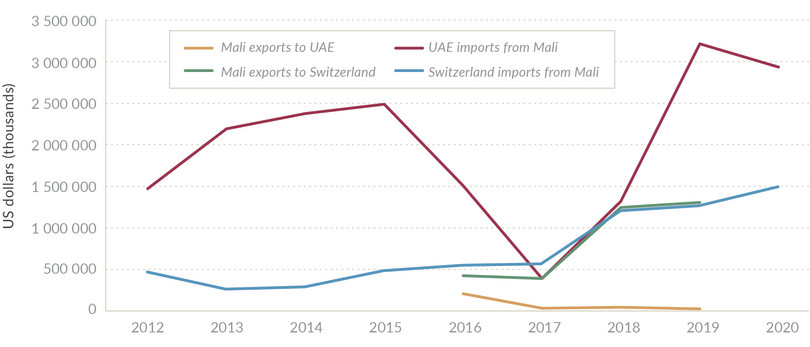

Figure 1 Mali gold trade with the United Arab Emirates and Switzerland.

NOTE: The discrepancy between the data tracking Malian imports to the UAE, and Malian export data to the UAE, points to a significant volume of undeclared exports.

UN Comtrade

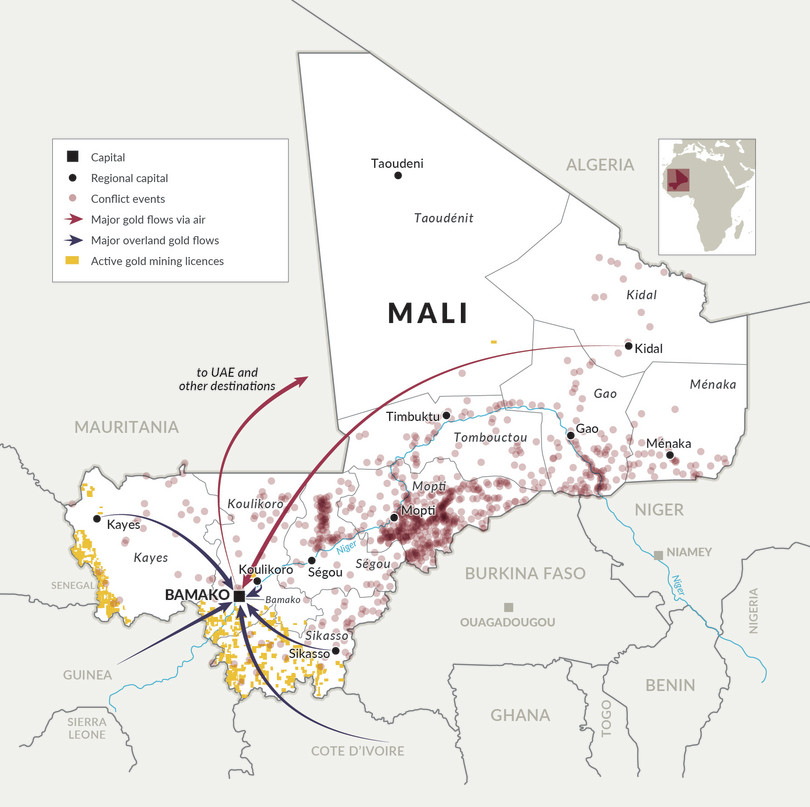

Gold is found in both southern and northern Mali. The most productive deposits are in the Kayes region and, to a lesser extent, in Koulikoro and Sikasso regions.16 Yet, growing insecurity in Mali threatens the future of the industrial gold sector, with attacks by jihadist groups increasingly targeting mining companies. For most of the past two years, the Kayes region has been targeted by violent extremist groups, most notably the Macina Liberation Front (Katibat Macina). In September 2021, the convoy of a mining company, which was being escorted by Malian armed forces, was attacked on the Bamako Kayes Road, with five gendarmes killed in the assault.17 While there is currently no industrial mining taking place in northern Kidal and Gao regions, both are reported to host hundreds of informal artisanal gold-panning sites.18 In the northern Kidal region, artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) is currently reported to be controlled by the non-state armed group Coordination of Azawad Movements (Coordination des mouvements de l’Azawad, CMA),19 which has been increasingly absorbed by the jihadist group Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) since 2021. If deemed profitable, Russian industrial-mining operations could be established in northern Mali in the near future, despite the security risks involved.

Figure 2 Mali’s active gold mining licences, security incidents and key supply-chain routes through Bamako.

NOTE: This map does not capture artisanal gold mining sites; conflict events data includes battles, violence against civilians and explosions/remote violence from 2020 to 2022.

Ministry of Mines of Mali Online Repository, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project

Since January 2022, Mali has been facing its own economic sanctions, with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) closing all land and air borders to the country,20 and the freezing of Mali’s assets held by the Senegal-based Central Bank of West African States. The sanctions are already being felt. As of February 2022, Mali had defaulted on FCFA54 billion (US$93 million) in interest and principal payments, according to the West Africa monetary union’s debt agency UMOA-Titres.21 The sanctions will not only prevent Bamako from being able to pay the state’s debt, they will also leave the country unable to pay for internal operations, including military operations.22 Sanctioned actors may therefore look to criminal networks to launder gold and money – while this can legally be done – in order to allow them to access markets in the UK, EU and US that have imposed sanctions against Russian entities.

Illicit networks linking West Africa and Russia

Sanctions regimes implemented by the UK, the EU (as well as Switzerland), the US and others are quickly cutting Russian entities out of international financial and gold markets. For example, LBMA rules state that gold trades cannot be conducted with any entities that will violate any EU, US, UK or any other relevant, economic and/or trade sanction lists.23 Yet, it is secondary sanctions – economic restrictions imposed on third parties who transact with sanctioned entities – that may be even more painful for Russia and its allies. Thus, even if transactions take place or assets are held outside the jurisdiction of a sending state, states can take action against a third party that transacts with a sanctioned actor if they hold assets or do business in the jurisdiction of the sending state.24 Sanctioned entities may still be able to access gold markets in states that have not adopted sanctions regimes, but the fear of violating secondary sanctions is likely to have a chilling effect on the formal gold sector more broadly, deterring gold buyers from buying Russian gold.

This is where criminal networks step in. By disguising the origins and ownership of gold, as well as the financial beneficiaries of gold transactions, Moscow and other sanctioned entities may be able to evade sanctions. While gold-mining operations in West Africa controlled by, or benefitting, sanctioned Russian entities tend to be industrial operations, they could make use of existing illicit supply chains linked to ASGM or establish new routes.25 Alternatively, sanctioned Russian entities could utilize private planes to fly gold directly from West African producer countries to Russia or other destination countries, a tactic that has been used by other illicit actors and countries seeking to evade sanctions in the past.26

In attempting to assess supply chains and the methods that sanctioned Russian entities may use to move and launder gold from the West African countries in which they are operating – most prominently, CAR and Mali –the movement of gold via established illicit supply chains and on private aircrafts should both be considered.

Gold-smuggling routes out of CAR

The high degree of scrutiny of CAR’s gold sector, makes it likely that actors seeking to disguise the origins of gold produced in the country would smuggle it over international borders, including into Cameroon, rather than mis-declaring the source of direct exports.

Figure 3 Central African Republic’s gold mining sites, security incidents and key supply-chain routes.

NOTE: Conflict events data includes battles, violence against civilians and explosions/remote violence from 2020 to 2022.

Alexandre Jaillon and Guillaume de Brier, Mapping Artisanal Mining Sites in the Western Central African Republic, IPIS and USAID, November 2019; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project

Companies owned and operated by Chinese nationals are also significant players in the CAR gold sector, and their exporting techniques highlight how sanctioned Russian entities may try to launder gold produced in the country.27 Many Chinese-owned companies operate semi-mechanized gold mines throughout western CAR and enjoy high-level political protection.28 Some Chinese mining operations are even thought to be engaged in large-scale gold smuggling, with several sources declaring that gold is smuggled by Chinese nationals from CAR to Cameroon.29 These companies are reported to pay a symbolic amount of export taxes in Bangui on a small portion of the gold produced and smuggle the rest of the gold over the border to Cameroon.30 From the border areas, gold is moved to Yaoundé and Douala, from where it is exported to China.31 Research on gold supply chains linked to small, mechanized gold operations owned or operated by Chinese nationals in West Africa indicates that these operations often fly gold directly to China.32

Most other illicit gold flows run through Cameroon towards the UAE. Research conducted by the GI-TOC between 2020 and early 2021 found that gold from western CAR is predominantly smuggled over the border to Cameroon or transported to Bangui and smuggled out through the airport. From eastern Cameroon and Bangui, the majority of gold is allegedly moved to Doula and flown out to the UAE through Douala airport.33 Gold from rebel-held zones in eastern Cameroon is reported to leave the country via Bangui or else is smuggled to neighbouring countries via terrestrial routes (including routes to Sudan) or using small clandestine aircraft.

Gold-smuggling routes out of Mali

Research conducted by the GI-TOC between 2021 and early 2022 indicates that the bulk of gold produced in Mali through ASGM is transported to Bamako. Gold produced in southern Mali is transported to Bamako by road, while gold produced in the north is transported to the capital by air, sometimes using MINUSMA flights.34 While a small amount of gold is transported to European or Asian countries, most of the gold passing through Bamako (produced in Mali or smuggled in overland) is transported to the UAE.35 Interviewees noted that smaller amounts of gold are smuggled out of Mali to neighbouring countries, such as Guinea, before being exported to the UAE.

UAE: A gold-laundering hub

As the current destination for most illicit gold flows out of CAR and Mali, the UAE is likely to play an important role in the ability of entities to evade sanctions. The UAE, specifically Dubai, is a dominant player in global gold and financial flows,36 linking African gold flows to Russia and the rest of the world. Most gold produced by ASGM is reportedly transported to the UAE,37 where it is traded and moved into broader global gold markets, including Switzerland and the UK. The UAE has sent mixed messages regarding their stance on Russia, voting in favour of the UN resolution condemning the Russian invasion of Ukraine after abstaining from the UN Security Council resolution.

Figure 4 UAE gold exports to countries that have imposed sanctions on Russian actors.

UN Comtrade

In March 2022, the UAE was added to the ‘gray list’ of the Financial Action Task Force, following a 2020 mutual evaluation that found weaknesses in the regulation of the gold trade and significant trade-based money-laundering risks.38 This means that the UAE will now be subject to greater oversight and will be required to implement an ‘action plan’ to demonstrate ‘a sustained increase in effective investigations and prosecutions of different types of money laundering cases consistent with UAE’s risk profile.’39 One element of the action plan is to proactively identify and combat sanctions evasion.40 Regulation of the gold sector will play an important role in these efforts.

Conclusion

Sanctions regimes instituted in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine give new meaning to Russian diplomacy and the growing presence of Russian actors in West Africa’s gold sector. The presence of Russian gold-mining operations and PMCs in West Africa, as well as Russia’s warm relations with regional governments, raises concerns that the gold sector could be an avenue to raise funds and launder gold to evade sanctions imposed against Moscow and other actors. The situation in West Africa is further complicated by the current ECOWAS sanctions against Mali and the country’s currency shortage, as well as security risks in CAR and Mali. Thus, there is reason to re-examine and continue to monitor Russia’s presence in the West African gold sector, as well as the role that criminal networks may play in disguising the origins of the gold and thus enabling sanctions evasion.

Notes

-

Henry Foy, et al., Russia: Vladimir Putin’s pivot to Africa, Financial Times, 22 January 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/a5648efa-1a4e-11e9-9e64-d150b3105d21. ↩

-

One Russian mining company has been operating in Kangaba, Koulikoro region, for nearly eight years; interview with Dario Littera, CEO Kankou Moussa refinery, March 2022. ↩

-

LBMA, Good Delivery List Update: Gold & Silver Russian Refiners Suspended, 7 March 2022, https://www.lbma.org.uk/articles/good-delivery-list-update-gold-silver-russian-refiners-suspended. ↩

-

Matt Egan, Putin has a pot of gold. Republicans and Democrats want to take it away, CNN, 11 March 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/03/11/business/russia-economy-sanctions-gold/index.html. ↩

-

For the list of operations sites, see https://nordgoldjobs.com/en/mines. ↩

-

Federica Saini Fasanotti, Russia’s Wagner Group in Africa: Influence, commercial concessions, rights violations, and counterinsurgency failure, Brookings Institution, 8 February 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2022/02/08/russias-wagner-group-in-africa-influence-commercial-concessions-rights-violations-and-counterinsurgency-failure. ↩

-

International Crisis Group, Making the Central African Republic’s Latest Peace Agreement Stick, Africa Report No. 277, 18 June 2019, https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/277-making-cars-latest-peace-agreeement-stick.pdf; Dionne Searcey, Gems, Warlords and Mercenaries: Russia’s Playbook in Central African Republic, The New York Times, 30 November 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/30/world/russia-diamonds-africa-prigozhin.html. ↩

-

US Department of the Treasure, Treasury Increases Pressure on Russian Financier, 23 November 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm1133. ↩

-

Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, CAR: Experts alarmed by government’s use of ‘Russian trainers’, close contacts with UN peacekeepers, ReliefWeb, 31 March 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/car-experts-alarmed-government-s-use-russian-trainers-close-contacts. ↩

-

Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic extended pursuant to Security Council resolution 2507(2020) (S/2020/662), ReliefWeb, 15 July 2020, https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/final-report-panel-experts-central-african-republic-extended-3. ↩

-

AFP, Mali accuses France of abandonment, approaches ‘private Russian companies‘, France 24, 26 September 2021, https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20210926-mali-accuses-france-of-abandonment-approaches-private-russian-companies. ↩

-

Jared Thompson, Catrina Doxsee and Joseph S Bermudez Jr, Tracking the Arrival of Russia’s Wagner Group in Mali, CSIS, 2 February 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/tracking-arrival-russias-wagner-group-mali. ↩

-

Felix Thompson, Mali Government Blames Sanctions for Treasury Bonds Default, VOA, 3 February 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/mali-government-blames-sanctions-for-treasury-bonds-default-/6425212.html. ↩

-

Marcena Hunter, Pulling at golden webs: Combating criminal consortia in the African artisanal and small-scale gold mining and trade sector, GI-TOC, 29 April 2019, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/pulling-at-golden-webs. ↩

-

Tiemoko Diallo and Nellie Peyton, Mali industrial gold production drops 2.6% to 63.4 tonnes in 2021, Mining.com, 10 February 2022, https://www.mining.com/web/mali-industrial-gold-production-drops-2-6-to-63-4-tonnes-in-2021. ↩

-

Currently the Kayes region accounts for 77% of official national production. Initiative pour la transparence des industries extractives (ITIE), Rapport ITIE-Mali pour l’annee 2018, December 2020, https://itie.ml/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Rapport-ITIE-Mali-2018-Final-Sign%C3%A9.pdf. ↩

-

Serge Daniel, Mali: cinq gendarmes tués dans une attaque jihadiste à l’ouest du pays, RFI, 29 September 2021, https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20210929-mali-cinq-gendarmes-tu%C3%A9s-dans-une-attaque-jihadiste-%C3%A0-l-ouest-du-pays . ↩

-

Interview with a gold-mining expert who visited all mining sites in Mali, Bamako, January 2022. ↩

-

Interview with primary actor in gold mining in Kidal, Bamako, January 2022. ↩

-

Christian Akorlie and Tiemoko Diallo, West African nations sever links with Mali over election delay, Reuters, 10 January 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/mali-eyes-elections-four-years-west-african-bloc-mulls-sanctions-2022-01-09. ↩

-

Paul Lorgerie and Tiemoko Diallo, Mali’s workers feel the squeeze as sanctions take hold, Reuters, 21 February 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/malis-workers-feel-squeeze-sanctions-take-hold-2022-02-21. ↩

-

Annie Risemberg, Mali government blames sanctions for treasury bonds default, Voice of America, 3 February 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/mali-government-blames-sanctions-for-treasury-bonds-default-/6425212.html. ↩

-

LBMA, Compliance and Risk Management, https://www.lbma.org.uk/publications/good-delivery-rules/compliance-and-risk-management. ↩

-

The US holds a unique jurisdictional edge in its ability to enforce secondary sanctions thanks to the dominance of the US dollar in international finance. US sanctions regimes state that ‘non-US persons can be held liable for causing violations by US Persons involving [specially designated nationals (SDNs), which are sanctioned individuals and entities] and can also be subject to secondary sanctions risks (which would include, in particular, the risk of designation as an SDN themselves) for providing ‘material support’ to SDNs.’ See Sylwia A Lis, Eunkyung Kim Shin and Taylor Parker, US Government Imposes Additional Sanctions on Russia, including the Central Bank of the Russian Federation; Implements Russia-related Executive Order, Sanctions & Export Controls Update, 2 March 2022, https://sanctionsnews.bakermckenzie.com/us-government-imposes-additional-sanctions-on-russia-including-the-central-bank-of-the-russian-federation-implements-russia-related-executive-order. ↩

-

While individually smaller than industrial enterprises, ASGM operations are estimated to produce billions of dollars of gold in Africa that is funneled through illicit supply chains annually; see Marcena Hunter, Pulling at golden webs: Combating criminal consortia in the African artisanal and small-scale gold mining and trade sector, GI-TOC, 29 April 2019, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/pulling-at-golden-webs. ↩

-

For example, the use of a Russian private plane to fly 7.4 tonnes of gold from Venezuela to Uganda in 2019; see Harry Holmes, President Maduro Linked to Ugandan Gold Probe, Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, 15 March 2019, https://www.occrp.org/en/daily/9381-maduro-linked-to-ugandan-gold-probe. ↩

-

Interviews with civil-society actors, Cameroon, December 2020. ↩

-

Interviews with diamond traders, Bangui, October 2020 and February 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with civil-society actors, Yaoundé and Bertoua, December 2020. ↩

-

It has been alleged that Chinese operations in CAR are financed by Cameroonian traders and that they sell gold at a discount (10%–15%) to them when they need local currency. Terah De Jong. (2019). Rapport diagnostic sur la contrebande des diamants en République centrafricaine, USAID, https://www.land-links.org/document/rapport-diagnostic-sur-la-contrebande-des-diamants-en-republique-centrafricaine, p 45. ↩

-

Interviews with civil-society actors and diamond traders, Cameroon, December 2020. ↩

-

Marcena Hunter, Pulling at golden webs: Combating criminal consortia in the African artisanal and small-scale gold mining and trade sector, GI-TOC, 29 April 2019, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/pulling-at-golden-webs; Marcena Hunter, Illicit financial flows: Artisanal and small-scale gold mining in Ghana and Liberia, OECD, 13 March 2020, https://www.oecd.org/dac/illicit-financial-flows-5f2e9dd9-en.htm. ↩

-

Interviews with diamond experts from CAR and Cameroon, June and July 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Interview with a primary actor in gold mining in Kidal, Bamako, January 2022. ↩

-

Focus group with the Union des comptoirs and raffineries d’or au Mali (UCROM), December 2021. ↩

-

Shawn Blore and Marcena Hunter, Dubai’s Role in Facilitating Corruption and Global Illicit Financial Flows, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 7 July 2020, https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/07/07/dubai-s-role-in-facilitating-corruption-and-global-illicit-financial-flows-pub-82180. ↩

-

Marcena Hunter, Pulling at golden webs: Combating criminal consortia in the African artisanal and small-scale gold mining and trade sector, GI-TOC, 29 April 2019, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/pulling-at-golden-webs. ↩

-

FATF, Mutual Evaluation of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), 30 April 2020, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/mutualevaluations/documents/mer-uae-2020.html. ↩

-

Ben Bartenstein and Abeer Abu Omar, UAE Added to Global Watchdog’s ‘Gray List’ Over Dirty Money, Bloomberg, 5 March 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-04/uae-added-to-global-watchdog-s-gray-list-over-dirty-money. ↩

-

FATF, Jurisdictions under increased monitoring – March 2022, 4 March 2022, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/high-risk-and-other-monitored-jurisdictions/documents/increased-monitoring-march-2022.html. ↩