Banditry in northern Niger: geographic diffusion and multiplication of perpetrators.

On 8 April 2022, two members of the Nigerien military were killed in a bandit attack near Plaque 50, an area close to the main road, 300 kilometres north-east of Agadez.1 The group of off-duty military personnel were travelling to Agadez in a rented vehicle when they were attacked by the armed bandits, who are likely to have mistaken them for civilians.2

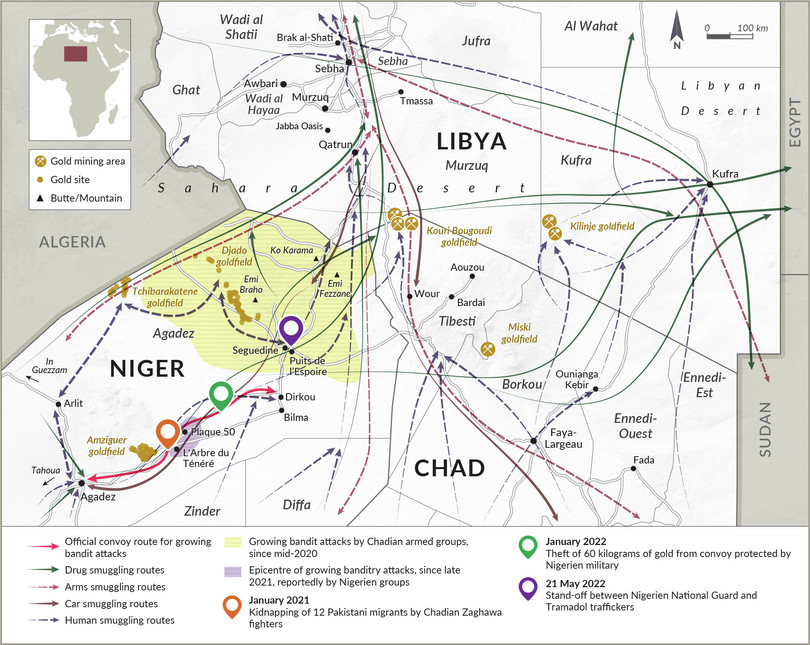

This incident highlights two trends shaping armed banditry dynamics in northern Niger since late 2021: the geographic diffusion of attacks, which have spread southwards from their original concentration in remote areas close to the Libyan border; and the fragmentation of actors behind the attacks, with both Libyan and particularly Nigerien criminal groups becoming increasingly prominent. These groups operate differently from Chadian armed groups, who are long-standing perpetrators of banditry in the swathes of Nigerien desert hugging the Libyan border.

Phases of the armed banditry economy of northern niger

Although armed banditry is not a new phenomenon in northern Niger, since 2016 it has grown as livelihood options have declined. The criminalization of human smuggling, which dealt a significant blow to local livelihood options, is one factor behind the growing intensity of banditry.3 Another is the increased smuggling of high-value commodities – such as drugs and vehicles – through north and north-west Niger, which is also rich in gold, making banditry there more lucrative.4

A further increase in banditry since July 2020 correlates with the growing presence of former Chadian mercenaries in southern Libya, as employment for Chadian fighters as mercenaries in the Libyan war has dwindled. Chadian mercenaries are particularly present at the Kouri Bougoudi goldfield, which straddles the Chad–Libya border, from where they engage in predatory activities across northern Niger.

The spate of attacks on convoys and groups near main roads closer to Agadez since late 2021, and the growing prominence of Nigerien groups, marks a further evolution of the region’s armed banditry economy, and further raises the protection risks faced by migrants transiting the region, most commonly through the services of human-smuggling networks.

Since the start of the second Libyan civil war in 2014, and particularly following the 2019–2020 LAAF Tripoli campaign, Chadian fighters have been key actors operating as mercenaries for both sides. As a relatively inexpensive yet experienced and expendable source of front-line fighters, Chadian mercenaries became valuable assets in the conflict. The 23 October 2020 ceasefire agreement signed between the UN-recognized Government of National Accord in Tripoli and the LAAF marked a de-escalation of conflict.

One of the key features of the ceasefire agreement was, in the words of the acting head of the UN mission in Libya, ‘the immediate and unconditional withdrawal of all foreign forces and mercenaries from the entirety of Libya’s territory’.5 While international attention focused predominantly on the departure of Russian- and Turkish-backed Syrian mercenary forces – seen as instrumental to achieving peace, given their support for opposing Libyan factions in the war – this decree similarly applied to Chadian fighters.

Although the agreement has not been fully implemented, the demand for mercenaries has waned, and many Chadian mercenaries have been demobilized and returned to bases in the desert south of Murzuq and close to the Kouri Bougoudi goldfield.6 Faced with dwindling revenue from mercenary engagement, Chadian fighters have consolidated their positions in Sahelian criminal economies, seeking to find new revenue streams and solidify existing ones.7

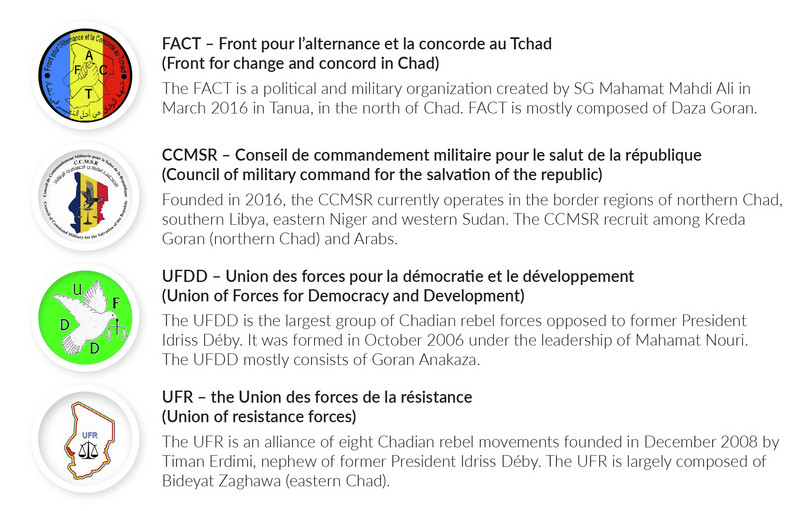

Figure 5 Prominent Chadian armed groups.

Chadian actors have therefore become increasingly involved in coordinating, providing protection for or attacking licit and illicit networks coordinating the transport, smuggling and trafficking of people, gold, vehicles, goods (including foodstuffs) and high-value drugs (such as cannabis resin and cocaine). The proceeds of such activities are significant. Chadian fighters escorting drug traffickers through northern Niger, northern Chad and southern Libya can earn up to around €5 000 per journey, while hijacking such convoys can earn up to six times that amount through sale of the seized goods.8

Since mid-2020, as growing numbers of Chadian former mercenaries turned to illicit markets for revenue, attacks on licit and illicit networks in northern Niger and Chad have spiked.9 Victims typically identify the armed groups responsible as Chadian, composed of members of the Zaghawa community from eastern Chad. These Chadian groups leverage their substantial combat experience from fighting in Libya’s internal conflicts, as well as ample hardware and vehicles acquired from the conflict, to operate across vast areas between northern Chad, northern Niger and southern Libya, and target well-armed criminal networks.

Groups move fluidly between transporting, protecting and preying on licit and illicit convoys. On 21 May, a member of the Nigerien National Guard on patrol near Seguedine, a town in the middle of the Sahara Desert in central eastern Niger, was killed while in a pursuit of suspected passeurs (smugglers), who are typically a source of revenue for the guards.10 Instead, the quarry turned out to be well-armed traffickers, who retaliated in face of pursuit, shooting at the guards’ vehicle and killing one. According to an actor familiar with the incident, the group ‘were Tebu traffickers of tramadol. They were not conducting a banditry operation at that time. But they could also turn to banditry on their next mission, after their trafficking operation.’11

Nigerien and Chadian security forces have been unable to contain their threat in the Chad–Libya–Niger tri-border area,12 which has spurred the creation of local armed self-defence groups to protect the ability of such pre-existing groups’ to participate in regional illicit economies. For example, in April 2021, around 60 Tebu passeurs created a ‘self-defence’ committee tasked with deterring bandit attacks in the tri-border area.13 While representatives of the committee reportedly tracked ‘a sharp reduction in attacks in the area’ in the months following the establishment of the self-defence committee, this decrease proved temporary, although the committee continues to mobilize on an ad hoc basis.14

Union des forces de la résistance vehicles, undated.

Photo: Social media

Figure 6 Areas of intensifying bandit attacks in northern Niger.

Late 2021 to present: geographic diffusion and actor fragmentation

Since late 2021, GI-TOC monitoring has tracked a tangible increase in attacks by Nigerien criminal groups on the main roads connecting Agadez and Dirkou, particularly concentrated around Plaque 50, the site of the April 2022 attack on Nigerien military officers.

These attacks are distinguishable from those typically perpetrated by Chadian armed groups, who predominantly operate in the vast desert areas in the extreme north of Niger and Chad, and on remote routes rather than close to main thoroughfares. Nigerien networks typically seek to steal fuel, vehicles and goods rather than the high-value commodities transiting the far northern areas, which are typically the target of Chadian armed groups. It is likely that these local bandits lack the operational capacity and combat experience of Chadian bandits.

A growing number of such attacks target human-smuggling convoys, presenting an escalating threat to migrants transiting the region.15 On 4 March, a convoy of circa 190 migrants expelled from Libya into Niger by Libya’s Desert Patrol Company was attacked twice by armed bandits: first, by Chadian bandits, immediately upon entering Nigerien territory; and second, by a different group of Nigerien nationals, far closer to Agadez, in the Plaque 50 area.16 According to one migrant travelling on the convoy, in the second attack: ‘The bandits came on the road, some guys came on motorbikes and robbed us; they did not kill anybody, but they carried guns, and the robbers were from Agadez.’17

Bandits have also targeted convoys carrying gold shipments from the Djado goldfields towards Agadez. For example, in January 2022, 60 kilograms of gold were stolen from a convoy protected by the National Guard.18

Stakeholders based in the region posit that an overall deterioration of economic opportunities is likely to be driving more actors to rely on banditry as an alternative livelihood. Further, the impunity enjoyed by the vast majority of attackers to date may have encouraged additional actors to seek a share of banditry proceeds.19

According to several contacts, the bandits appear undeterred by the presence of military personnel, and regularly target vehicles travelling with the military convoy between Agadez and Dirkou.20 The Nigerien military is ill-equipped to respond to banditry, and has on occasion been said to avoid crossing paths with heavily armed bandits.21

Implications

Armed banditry is a growing threat across expanding areas of Niger, as alternative livelihoods dwindle and conflicts in the country’s neighbouring states have cross-border implications. Although a long-standing phenomenon in northern Niger, banditry has intensified since late 2021, including between Agadez and Dirkou, south of the remote north-east already afflicted by Chadian attacks.22

The poor reintegration prospects faced by members of Chadian armed groups mean that they are likely to continue being prominent players in armed banditry. The Chadian government has a poor track record with disarmament, demobilization and reintegration processes, discouraging Chadian fighters from surrendering to government forces. As the Libyan ceasefire holds and Chadian fighters face dwindling revenues from mercenary work, they are likely to continue seeking revenue from the criminal economy of the central Sahara.23 While the ‘national dialogue’ promised by the Transitional Military Council as a stepping stone to elections raised hopes that some fighters would be able to return home,24 its repeated postponement has dashed these. On 2 May, authorities announced the indefinite postponement of the dialogue, originally intended to occur in December 2021, pointing to a drawn-out period of political stalemate with few concrete attempts to re-engage with current and former rebels.

Nigerien’s lucrative banditry economy is swelling: new players are attracted as alternative livelihoods become scarcer, while long-standing players face limited exit prospects. Banditry erodes existing livelihoods, raising costs for both licit and illicit operators in the region, and compounding existing economic strain. As Africa is buffeted by spiralling global inflation rates and economic woes look set to grow, banditry appears set to become an ever-greater problem in Niger.

In northern Niger, according to a contact close to the Seguedine ‘self-defence committee’: ‘The best way to effectively fight against banditry activities is through collaboration between the civilian population of the area with the Nigerien army, and that [the latter carries out more official actions against bandits].’ Given the Nigerien army’s limited resources, particularly considering the vast terrain under their mandate, such steps appear distant. As the contact concluded, ‘this phenomenon is far from over.’25

Notes

-

Ibrahim Diallo, Axe Agadez-Bilma: une attaque de bandits armés fait deux morts et quatre blessés parmi les militaires nigériens, Aïrinfo Agadez, 9 April 2022, https://airinfoagadez.com/2022/04/09/axe-agadez-bilma-une-attaque-de-bandits-armes-fait-deux-morts-et-quatre-blesses-parmi-les-militaires-nigeriens. ↩

-

The number of casualties among the bandits is unknown, but they were reportedly able to escape. ↩

-

Human-smuggling convoys have been more vulnerable to bandit attacks since the criminalization of the transport of migrants in 2016, and particularly since the closure of Niger’s land borders in March 2020, as migrant smugglers have increasingly adopted remote routes for fear of being arrested by security forces. These routes coincide with those used by the traffickers of drugs and arms, exposing migrant smugglers to banditry. Nigerien authorities recognize that an increase in banditry since 2016 can be attributed to the enforcement of Law 2015-036. See J Tubiana, C Warin, and GM Saeneen, Multilateral Damage – The impact of EU migration policies on central Saharan routes, September 2018, Clingendael Institute, https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2018-09/multilateral-damage.pdf. ↩

-

One particular bandit group, operating around the Djado plateau, has frequently targeted drug traffickers and artisanal miners travelling between Djado and the Tchibarakatene goldfield since 2017. ↩

-

European Union External Action, Libya: Joint Statement by the Quartet, 20 April 2022, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/96947/libya-joint-statement-quartet_en. ↩

-

These bases are ideally positioned for preying upon high-value drug convoys running through the Salvador Pass and east of the Toummo crossing. ↩

-

This process started since the LAAF loss in May 2020 of the strategic al-Wattiya airbase, and in June 2020 the city of Tarhouna, which paved the way for the ceasefire. ↩

-

Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi, Lost in trans-nation: Tubu and other armed groups and smugglers along Libya’s southern border, Small Arms Survey, December 2018, https:/www.smallarmssurvey.org/sites/default/files/resources/SAS-SANA-Report-Lost-in-Trans-nation.pdf. ↩

-

For example, on 6 November 2021, two drug-trafficking groups clashed around the Salvador Pass. Chadian Goran Anakaza traffickers based in Qatrun were transporting cannabis resin when they were attacked by Chadian Zaghawa traffickers. Interview with Chadian Goran drug trafficker based in Qatrun, autumn 2021, remote. ↩

-

Aïr-Info Agadez, Facebook, 23 May 2022, https://www.facebook.com/PAirInfoAgadez/photos/a.1065483263536968/5127991147286139. ↩

-

Interview with Nigerien contact familiar with the incident, spring 2022. ↩

-

Several arrests have taken place – Nigerien forces reportedly arrested at least 10 suspected bandits near Dirkou in September 2020, and a group of over 20 armed men were apprehended in November 2020 in the Madama area. GI-TOC interviews with multiple contacts in northern Niger suggest that these arrests are insufficient to address the long-term threat presented by armed banditry in Niger. See also Tadress24info, Facebook, 20 September 2020, https://www.facebook.com/tadress.info/posts/1452576208283830; and Tadress24info, Facebook, 27 November 2020, https://www.facebook.com/tadress.info/posts/1516354988572618. ↩

-

Contacts close to the committee claim that the move was necessary in the absence of any credible and effective efforts by the Nigerien military to curb the rise of banditry in the area. The committee draws on the support of the Tebu community in Niger, Libya and Chad. Its formation is illustrative of the strategic importance of community solidarity for Tebu passeurs and the vital need to safeguard smuggling activities for local Tebu livelihoods. ↩

-

Interview with contact close to the self-defence committee, spring 2021. ↩

-

In January 2021, a group of 12 Pakistani migrants were kidnapped by Chadian bandits while travelling via the Kouri Kantana route. See Alexandre Bish, Soldiers of Fortune: The Future of Chadian Fighters after the Libyan Ceasefire, GI-TOC, December 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/chadian-fighters-libyan-ceasefire. ↩

-

Victims reported that the perpetrators of the first attack intended to kidnap women, but instead the attackers took only cash. It is unclear why the kidnapping did not occur. Information gleaned from GI-TOC monitoring in the region. ↩

-

Interview with a migrant expelled from Libya, spring 2022. ↩

-

Aïr-Info Agadez, Facebook, 30 January 2022, https://www.facebook.com/PAirInfoAgadez/photos/a.1065483263536968/4801167979968459/. ↩

-

Information from ongoing GI-TOC monitoring of North Africa and the Sahel. ↩

-

With dozens of vehicles joining the convoy each week, bandits are able to enter the convoy discreetly and force drivers to stop in order to either hijack the vehicle or steal its contents and cash. ↩

-

For example, in the 21 May incident outlined above, the officers of the National Guard allegedly broke off pursuit as soon as it became clear that their quarry were traffickers. Interview with Nigerien stakeholder close to the incident, spring 2022; interviews with multiple contacts in spring 2021. ↩

-

Since 2017, the Maradi region in Niger’s southern borderlands has also been increasingly afflicted by armed banditry spilling over from Nigeria’s north-western regions. See Institute for Security Studies, Organised banditry is destroying livelihoods in Niger’s borderlands, 16 May 2022, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/organised-banditry-is-destroying-livelihoods-in-nigers-borderlands. ↩

-

See Alexandre Bish, Soldiers of fortune: The future of Chadian Fighters after the Libyan ceasefire, GI-TOC, December 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/chadian-fighters-libyan-ceasefire. ↩

-

These hopes were further stoked by the amnesty granted to 296 rebels and political dissidents by the government in November 2021. ↩

-

Interview with contact close to ‘Self-defence committee of Seguedine Smugglers’, spring 2021. ↩