Cattle rustling spikes in Mali amid increasing political isolation: Mopti region emerges as epicentre.

On 18 June 2022, suspected Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) jihadists killed at least 20 civilians and seized cattle belonging to residents of Ebak village in Anchawadi commune.1 The gunmen arrived in Ebak, 35 kilometres north of Gao, on motorbikes. This attack was typical of the ISGS, which is known to operate in Mali’s Gao region.2

Three months earlier, on 19 March 2022, residents of Niougoun, a village in Segou region in central Mali, lost more than 200 heads of cattle to suspected jihadists.3 After several futile missions to recover the cattle, traditional hunters known as the Dozo, who provide security in the area, instead unlawfully seized a handful of heads of cattle from a neighbouring village. This episode sparked a stand-off between the two communities and local police, with tensions rising as women and young people took to the streets to protest, demanding the release of the stolen cattle.

This incident in Segou is merely one of many currently fuelling tensions between different factions of communities, and with law enforcement, across central Mali and also in the north of the country. According to one village chief in northern Mali’s Timbuktu region, ‘cattle rustling is directly linked to the current armed conflict, as communities launch retaliatory attacks and counter attacks in Mali and in the border areas.’4

Although cattle rustling is not a new phenomenon, since 2017, armed-group involvement in the industry in central and northern Mali has vastly swollen the scale of the market, and its associated profits. According to official figures, the volume of cattle rustled in Gao, Ménaka, Mopti and Timbuktu regions in Mali in 2021 was unprecedented.

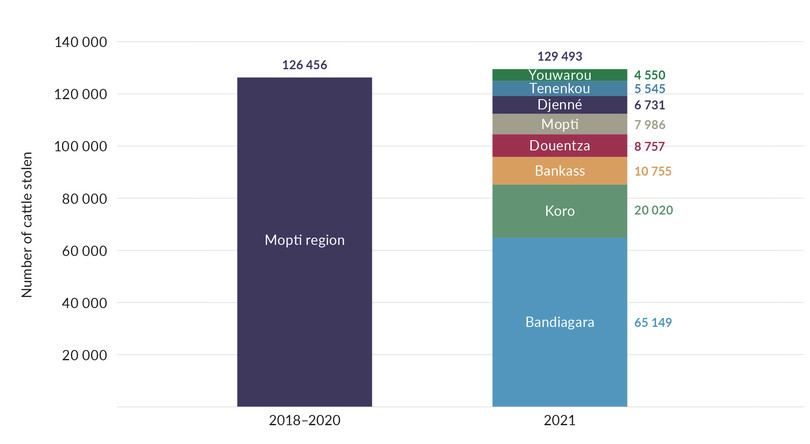

In Mopti region (central Mali), the number of cattle stolen rose threefold, from an average annual figure of approximately 42 000 to almost 130 000 in 2021.5 Community members and local officials interviewed in Mopti, Gao, Ménaka and Timbuktu regions in March and April 2022 confirmed that cattle rustling has since continued to escalate across the first half of 2022.6

Yet, in parallel to this escalation, state responsiveness in many parts of these regions has reportedly decreased over the past year.7 According to one community leader in Timbuktu region, while ‘jihadists go wherever they want on motorcycles, even in areas where bans on motorbikes and vehicles remain in force,’8 local administration and security officials of the Malian government have increasingly moved to nearby urban areas, and are less likely to act on cases of cattle rustling reported to them.9 Interviews with other community members in these regions confirmed these trends.10

The involvement of armed groups in cattle rustling, and the confinement of many state officials to urban centres in these regions in central and northern Mali, appears to have accelerated in the wake of the 2021 and 2022 withdrawals of French and other European forces in response to diplomatic and political fallout between Mali and its key Western partners.11

Cattle rustling in mali escalates since 2021

Previously limited and occurring sporadically, cattle rustling has grown into a major threat since the onset of the Malian security crisis in 2012. According to the president of Bamako district’s Regional Chamber of Agriculture, ‘it is no longer simple theft, but looting of herds. They gather hundreds or even thousands of cattle and sell them in neighbouring countries.’12

While prior to the present security crisis cattle rustling was largely considered a form of ‘ordinary banditry’, since 2017 it has evolved into a highly organized form of criminality, involving a wide range of different actors, including bandits and armed groups with or without ideological orientation, including extremist groups.13

Cattle rustling reached new volumes in 2021 (with over 170 000 heads of cattle reported stolen) and has reportedly continued to grow throughout the first half of 2022.14 The Mopti region – where over 125 000 cattle were reported stolen in 2021 – is the epicentre of cattle-rustling activity in the country, with Badiagara and Koro cercles particularly affected.15 According to official figures, the number of rustled herds in Mopti in 2021 rose to more than those recorded in 2018, 2019 and 2020 combined (see Figure 1).16

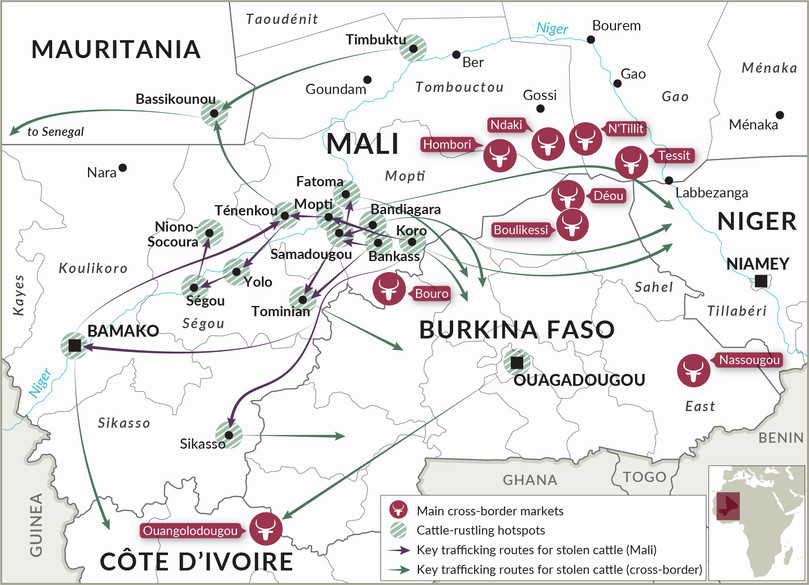

Herds from Koro, Bandiagara and Bankass – the three cercles in Mopti region with the largest number of stolen cattle in 2021 – are transported to Burkina Faso and Niger via key transit nodes such as Sikasso, Bamako and Mopti, as well as to Mauritania through Ouroali and Tenenkou.17

The 2021 uptick in cattle rustling has occurred in parallel with Mali’s growing political isolation, and linked shifts in the country’s security tectonics. In Mopti region, since December 2021, the Malian military has intensified joint operations with the Wagner Group.18 At the same time, the Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) has reportedly experienced increased access challenges.19 Concerns regarding human rights violations by military officers in Mopti escalated in the second quarter of 2022.20 The February announcement of the withdrawal of French troops from Malian territory, and the May announcement of Mali’s exit from the G5 Sahel, including the joint force aimed at combating armed groups in the region, signal further political isolation.21 Although MINUSMA’s mandate is expected to be renewed on 30 June, it is likely that the UN peacekeeping mission will continue to face operational and security challenges, particularly in Mopti region, in light of the increasing political isolation on the part of the Malian transitional authorities.

Figure 1 Cumulative number of cattle stolen in Mopti region, Mali, 2018–2020 versus 2021.

Office of the Governor of Mopti Region, Report of the regional conference on cattle theft in the Mopti region, Ministry of Territorial Administration and Decentralization, 7 December 2021

The central role of armed groups in cattle rustling

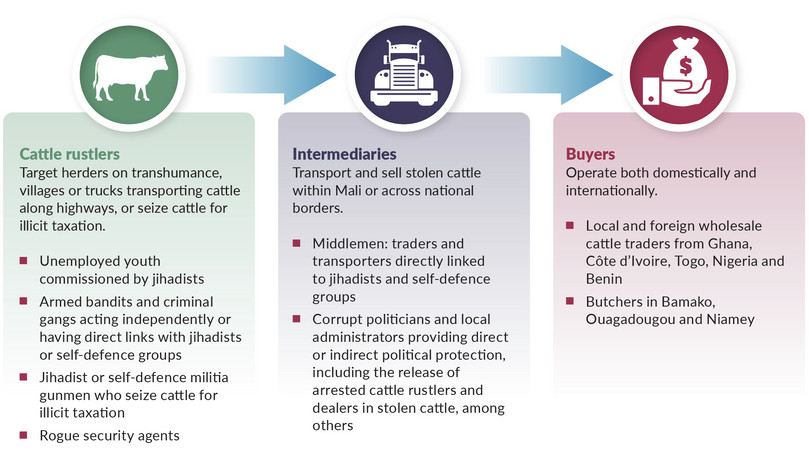

Armed groups in Burkina Faso and Mali, including jihadist groups, are central players in the lucrative cattle-rustling economy.22 Additional pivotal players include transporters, who drive trucks long distances to major cities within Mali and across the borders; traders who coordinate the sale of cattle at local and cross-border markets; and state-embedded actors, including corrupt individuals in the military, security forces, state administrators and politicians, who protect or turn a blind eye to the trade (see Figure 2).23

Armed groups operating in Mopti region target cattle while they are grazing in fields, being herded on transhumance routes or transported in trucks along key roads.24 In one instance, in Mopti region’s Djenné cercle in October 2021, herders who had moved their cattle to pastures in nearby Méma Plains pasturelands 25 were robbed of their herds by bandits as they sought to return home. Herders who offered any resistance were kidnapped and their families forced to give cattle as ransom.26 In some cases, trucks transporting already stolen cattle are themselves the target of attacks.

Armed-group tactics exploit existing community vulnerabilities. According to a herder in Timbuktu region, armed groups regularly engage groups of unemployed youth, arm them, instruct them to carry out cattle-rustling attacks on their behalf, and reap the majority of the proceeds.27 This creates a cycle of vulnerability: a cattle owner in Timbuktu region noted, ‘any youth in Mali who saw their parents being robbed of herds by bandits, or lost their parents to bandits, jihadists or the military, have become easy prey for bandits and jihadists to recruit.’28

Figure 2 Stolen-cattle supply chain involving local and foreign actors.

In some areas of central Mali and northern Burkina Faso, extremist groups exert a significant degree of control over the cattle-rustling market, dictating prices and trading mechanics. For instance, in 2020, local criminal-gang leaders in northern Burkina Faso with direct links to al-Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) rescheduled previously regular market days so that they could sell stolen herds quickly on ad hoc days to beat spot-check patrols by French troops and spontaneous drone strikes by foreign forces.29

Figure 3 Cattle-rustling routes in the Liptako–Gourma area.

In return for protection, jihadists also impose herd taxes on whole villages or larger areas under their control. This policy is enforced through the seizure of cattle from non-compliant villagers.30 For example, since 2021, Youwarou cercle in Mopti region has been under significant control of the Katibat Macina (a constituent group of JNIM), which imposes zakat on the owners of herds. Katibat Macina gunmen demand a bull calf for every 30 heads of cattle and a heifer calf for every 40 heads of cattle. The jihadists sell the zakat cattle on the local markets and pocket half of the proceeds, distributing the other half to vulnerable members of the community.31

The unprecedented 2021 surge in levels of cattle rustling, particularly in Mopti region, has, according to community members and livestock traders interviewed, been continuing unabated in the first half of 2022. The intensification of cattle-rustling activity in central Mali and surrounding regions has occurred in parallel with shifting power dynamics between the armed groups responsible for the overwhelming majority of cattle-rustling incidents, Malian state forces and the international forces present in the country. The restructuring of the political and security landscape in Mali has seemingly led to greater impunity for both non-state actors and state or state-affiliated actors linked to the cattle-rustling economy in central Mali.

Snapshot: cattle-rustling profits reaped by ansar al-islam in burkina faso

Cattle in Koriomé village on the banks of Niger River.

Photo: Timbuktu Centre for Strategic Studies on the Sahel

Although the Mopti region is the epicentre of cattle-rustling activity in the Sahel, many other areas are severely affected by this illicit economy. A significant proportion of cattle rustled in Mali is transported across the border into neighbouring Burkina Faso, where major profits can be made through the sale of stolen livestock.

As in Mali, armed groups in Burkina Faso are intimately involved in the illicit economy. Between 2017 and 2021, the Islamic State-linked Ansar al-Islam group sold millions of heads of cattle and other livestock across the country.32 Jihadist-linked traders receive between 80 and 100 heads of cattle each to sell at very low prices, ranging from FCFA175 000 to FCFA200 000 per head. One Burkinabe livestock trader close to Ansar al-Islam said: ‘This is really profitable for small-scale traders in the area, where the price of a cow varies between FCFA250 000 and FCFA500 000. We make huge profits from the herds we buy from jihadists, even though we know it is illegal.’33

Figure 4 Cattle-rustling hotspots and the presence of armed groups and international forces.

NOTE: *French armed forces’ withdrawal from the military base in Gao is planned for the end of the summer.

Notes

-

Mariam Coulibaly, Mali: une vingtaine de civils tués dans une attaque au nord de Gao, de nombreux déplacés, L’Infodrome, 20 June 2022, https://www.linfodrome.com/afrique-monde/78234-mali-une-vingtaine-de-civils-tues-dans-une-attaque-au-nord-de-gao-de-nombreux-deplaces. ↩

-

Agence France-Presse, Au moins 20 civils et un Casque bleu tués par des hommes armés, La Presse, 19 June 2022, https://www.lapresse.ca/international/afrique/2022-06-19/mali/au-moins-20-civils-et-un-casque-bleu-tues-par-des-hommes-armes.php. ↩

-

Demba Konte, Dougabougou, Cercle de Segou: Vive tension entre forces de l’ordre et la population à Niougoun suite à la disparition de plus de deux cent têtes de bétails, Le Nouvel Horizon, 29 March 2022. ↩

-

GI-TOC cattle rustling research interview with a village chief in Diré, Timbuktu region, 18 March 2022. ↩

-

Office of the Governor of Mopti Region, Report of the Regional Conference on Cattle Theft in the Mopti Region, Ministry of Territorial Administration and Decentralization, 7 December 2021. ↩

-

Interview with an official of the Bamako Regional Chamber of Agriculture, 20 March; the official said: ‘Mali has to enhance its security, its policing of borders with and work with neighbouring countries in order to regulate the movement of livestock. Otherwise the current situation can only escalate going forward’; interview with commander of a former rebel group in Timbuktu region, 23 March 2022, who said: ‘Herders have to watch their cattle rustled every year in a situation that keeps worsening, as terrorist groups and rebels in collusion with traditional leaders, traders and transporters organize themselves further to rustle cattle in northern and central Mali in order sell them in Bamako.’ ↩

-

The 7 December 2021 report of the Office of the Governor of Mopti Region, cited above, gives the example of Bankass town, where security forces were concentrated leaving the rest of the cercle at the mercy of armed groups that attack villages with impunity. Media reports in late May 2022 suggested that the task of fighting jihadists in Ménaka region had been left to a former rebel group allied to the government. See China.org.cn, Mali: le MSA annonce avoir tué une trentaine de terroristes (communiqué), 28 May 2022, http://french.china.org.cn/foreign/txt/2022-05/28/content_78241485.htm. In the 28 May 2022 report, the Movement for the Salvation of Azawad (MSA) urged the Malian and Nigerien governments to do everything in their powers to stop the spate of ongoing mass crimes through which populations are being wiped out and the destruction of the local economy through cattle rustling. ↩

-

Interview with a community leader in northern Mali’s Ménaka region, 18 March 2022. The ban on motorbikes and other vehicles was introduced as part of a counter-terrorism operation code-named Dambé. ↩

-

The two key jihadist umbrella groups are al-Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and the establishment of a new cell called the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS). The key self-defence militias are Alliance for Security in the Sahel (ASS) and the Dogon militia group Dan Na Ambassagou (‘Hunters Dedicated to God’). Former rebel groups include Imghad Tuareg Self-Defence Group and Allies (GATIA), the High Council for the Unity of Azawad (HCUA) and the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA). ↩

-

Interview with the president of Bamako district’s Regional Chamber of Agriculture, 17 March 2022; interview with a community leader in Ménaka region, 18 March 2022; interview with a village chief in Diré, Timbuktu region, 18 March 2022. ↩

-

Counter Extremism Project, Mali: Extremism and Terrorism, 2022, https://www.counterextremism.com/countries/mali/report. ↩

-

Interview with the president of Bamako district’s Regional Chamber of Agriculture, 17 March 2022. ↩

-

William Assanvo, et al., Violent extremism, organised crime and local conflicts in Liptako-Gourma, Institute for Security Studies, December 2019, https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/war-26-eng.pdf. ↩

-

Figures provided by the Malian Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries show that the more than 125 000 heads of cattle stolen in Mopti region was more than two thirds of the total number (over 170 000 heads of cattle) stolen in all the regions most affected by cattle rustling (Mopti, Gao, Ménaka, Segou and Timbuktu) put together. ↩

-

The most affected communes in the Badiagara and Koro cercles (second-level administrative units) are Séguéiré, Métoumou, Diamnati, Wadouba and Kéndié. ↩

-

Office of the Governor of Mopti Region, Report of the Regional Conference on Cattle Theft in the Mopti Region, Ministry of Territorial Administration and Decentralization, 7 December 2021. ↩

-

The main destination markets are located along the Mali–Burkina Faso border, including Bouro in Soum, Deou in Oudalan, and Nassougou in Fada N’Gourma (capital of Burkina Faso’s East region and Gourma province). ↩

-

Security Council, Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Mali, 2 June 2022. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

AFP, Mali junta breaks off from defence accords with France, France24, 3 May 2022,https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20220502-mali-junta-breaks-off-from-defence-accords-with-france; AFP, Mali withdraws from G5 Sahel regional anti-jihadist force, France24, 16 May 2022, https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20220515-mali-withdraws-from-g5-sahel-regional-anti-jihadist-force. ↩

-

Notable armed groups include Ansar al-Islam, Serma Katiba, Volontaires de la défense de la patrie (Volunteers for the Defence of the Fatherland, VDP) and self-defence group Koglweogo in Burkina Faso, as well as Katibat Macina (the Macina Liberation Front), GATIA, HCUA, MNLA, and Dan Na Ambassagou in Mali. ↩

-

Interview with an armed-group leader in Timbuktu region, 23 March 2022; interview with a community leader in Ménaka town, 18 March 2022. ↩

-

For instance, in Koro, Bandiagara and Douentza, armed groups rustle herds in villages and engage in highway robbery, targeting trucks transporting stolen and rustled herds. Office of the Governor of Mopti Region, Report of the Regional Conference on Cattle Theft in the Mopti Region, Ministry of Territorial Administration and Decentralization, 7 December 2021. ↩

-

The Méma is land rich in alluvial deposits, situated north of Massina, south-west of the Lakes Region, and west of Lake Debo and the Inner Niger Delta. ↩

-

Interviews with various stakeholders in Koro, 8 April 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a herder in Timbuktu region, 24 March 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a cattle owner in Timbuktu region, 24 March 2022. ↩

-

Interviews with residents of northern Burkina Faso’s Gorom-Gorom town, September 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with various stakeholders in Koro, 8 April 2022. ↩

-

Interviews with various stakeholders in central Mali, 30 March to 3 April 2022. ↩

-

Interviews with Burkinabe traders in Gorom-Gorom town, September 2021, including detailed account by Burkinabe livestock trader close to Ansar al-Islam. ↩

-

Interview with a Burkinabe livestock trader close to Ansar al-Islam, September 2021. ↩