Rise in cyanide-based processing techniques changes criminal dynamics in gold mines in Burkina Faso and Mali.

A young man processes artisanally mined gold.

© Pascal Parrot via Getty Images

Propelled by the discovery of a Saharan gold vein in 2012, there has been a rapid proliferation of artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) in Burkina Faso and Mali. This has been underpinned by growing illicit markets in cyanide, a chemical that is widely used in the gold-extraction process.1 Besides the detrimental environmental and health impacts caused by its use,2 this illicit trade in cyanide is also affecting security dynamics in West Africa.

On the one hand, the chemical is trafficked along well-established transnational smuggling routes, reinforcing existing patterns of criminality and corruption. On the other, although cyanide processing increases the profitability of ASGM (cyanide processing recovers a greater amount of gold from ore than mercury processing), it requires greater investment, favouring wealthier actors in ASGM supply chains, thus depriving vulnerable communities of income opportunities.3 This greater level of financial investment tends to be the preserve of more powerful actors, including foreign nationals and political elites, and can enhance the influence of criminal networks in ASGM supply chains.4

Many ASGM sites in Burkina Faso and Mali are in areas where there is limited state presence and where non-state armed groups are active.5 A number of sites are under the control of such groups, including ones affiliated with Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) a jihadist coalition reportedly linked to al-Qaeda.6 In other sites, armed groups tax ASGM proceeds, run protection rackets and control access to the sites.7 In areas not controlled by armed groups, criminal networks that facilitate the trafficking of cyanide play a key role in perpetuating social tensions that have the potential to create the conditions for further insecurity in an already volatile region.8

Burkina Faso, a key hub for cyanide trafficking

Since around the middle of the last decade, shortly after the adoption of cyanide-based processing techniques at ASGM sites in the country,9 Burkina Faso emerged as a major hub for cyanide trafficking in West Africa.10 Networks trafficking cyanide into Burkina Faso follow routes established for the smuggling of consumer goods from Benin, Togo, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire.11 As a landlocked nation, Burkina Faso relies heavily on products imported from these coastal states. Price discrepancies between goods in Burkina Faso and its coastal neighbours, combined with non-competitive domestic monopolies over certain products, such as fuel and cigarettes, create the conditions for thriving contraband economies.

This constitutes an enormous political economy, much of which is tolerated by government authorities. ‘You can’t target the [smugglers] because it will destroy local economies,’ explained a government deputy from a town that is a key trafficking hub near the Burkina Faso–Togo border. ‘The local border authorities and gendarmerie are part of the system,’ he said.12

Small-time traffickers and traders based in border communities who moved items such as car batteries and tyres across the border in the 1990s gradually diversified their portfolios. ‘Since the early 2000s, traffickers operating along these routes have evolved,’ explained a local researcher. ‘They are now [major traders] who have contacts on both sides of the border and have got involved in other things,’ he said. ‘Now it is mercury, cyanide, [motorbikes], drugs … anything.’13

Fuel smuggling, particularly from Benin and Togo (with the fuel often sourced from Nigeria), is among the most organized and lucrative of these illicit markets, and provided the infrastructure on which cyanide trafficking networks operate.14 Networks involved in fuel smuggling were able to easily incorporate cyanide because the modalities used to traffic the chemical across the border are nearly identical to how they smuggle fuel.15 Large trucks transport drums of fuel and cyanide from Togo and Benin to the border with Burkina Faso, where they either cross the border with the complicity of customs authorities or park near the border. In either case, the drums are offloaded at night, and fuel and chemicals are then transferred into smaller containers and transported by smugglers using motorbikes.16

Figure 5 Main routes of cyanide smuggling into and within Burkina Faso.

An artisanal gold mining site in Sadiola, Mali.

In cases where the trucks do not cross into Burkina Faso, smugglers cross the border using a network of paths and dirt roads that allow them to evade formal border crossings. In addition to collaborating with local authorities, smugglers have developed a system of lookouts and informants that ensure they can cross the border without being apprehended.17 In some cases, complicit Burkinabe authorities will mark the vehicle as ‘broken down’, seemingly knowing full well that, although the truck did not cross the border, the merchandise inside did.18

Cyanide is also trafficked into Burkina Faso along established trafficking corridors from northern Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire.19 According to a Burkinabe law enforcement official, the networks based in north-eastern Ghana that traffic cyanide into Burkina Faso are also involved in trafficking explosive materials, and may have access to them via industrial mining sites.20 Most cyanide smuggled into Burkina Faso is reportedly taken to the capital, Ouagadougou, although some is sent to the south-west of the country via Kpuéré and Gaoua, and thence directly to distributors operating there.

Ouagadougou serves as the key hub for cyanide smuggled into Burkina Faso, where it is often kept in warehouses and private residences. Once in Ouagadougou, vendors sell and transport the chemical to a number of locations throughout the country as well as to Mali.21 The cities of Koudougou and Bobo-Dioulasso are also major hubs (see the map).22 A source who had previously been involved in transporting fuel and cyanide added that there are also smaller depots throughout the country closer to mining areas.23

Black market prices for cyanide in Burkina Faso vary according to location and availability. Gold miners interviewed provided estimates in the range of FCFA 175 000–FCFA 250 000 (€267–€381) for 25 to 30 kilograms of cyanide, with most reporting prices at the higher end of this range.24 Most cyanide trafficked into Burkina Faso is in powder form.25

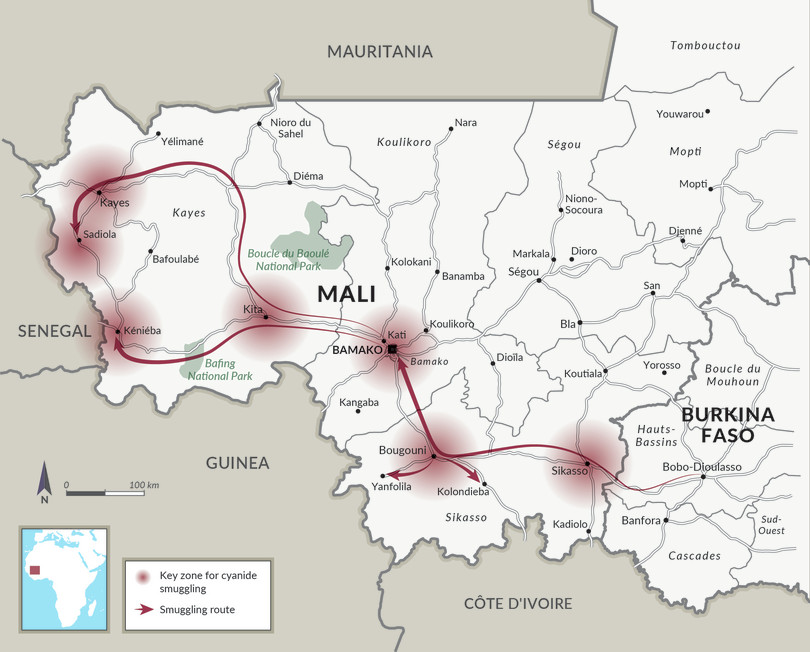

Figure 6 Main routes of cyanide smuggling from Burkina Faso to Mali.

Crossing into Mali

Cyanide is smuggled to Mali from Burkina Faso along routes that link Bobo-Dioulasso with Sikasso, in south-eastern Mali. Once in Sikasso, it is then smuggled west to Bougouni, a key transit point with direct links to the capital, Bamako, as well as to ASGM sites throughout Sikasso region.26 Once in Bamako, cyanide is transported to a number of ASGM sites in the Kayes region, notably to the cities of Kayes, Sadiola and Kenieba.27 Organized networks of vendors, many of whom are Burkinabe nationals, are based in the area and facilitate the transport and sale of cyanide as well as explosive materials sourced throughout West Africa.28 The scale of the cyanide market in the Kayes region is significant: one researcher specializing in ASGM dynamics in the area indicated that the trade in mercury and cyanide as among the biggest illicit markets there.29

Cyanide is also smuggled directly into the Gao region in northern Mali from north-eastern Burkina Faso, along contraband routes that pass through the Sahel Reserve via Gorom-Gorom and Markoye.30 The chemical is then transported to mining sites throughout the Gao and Kidal regions and, to a lesser extent, Timbuktu.31 Unlike in the southern regions of the country, the cyanide market in northern Mali is not heavily influenced by Burkinabe networks; instead, actors from Niger and Chad and, to a lesser extent, Sudan, are heavily involved.32

A less common entry point for cyanide into Mali is the Mopti region, which borders some of the key ASGM areas in the Nord and Sahel regions of Burkina Faso. These routes and itineraries are less defined, and likely the result of individual actors purchasing smaller quantities from gold mining sites in the Nord region for onward movement and sale in the Timbuktu region.33

The smuggling of cyanide to northern Mali points to growing use of cyanide processing in the region. As noted above, the process requires a degree of investment that investors are typically reluctant to commit to in cases where conditions are unstable and destruction or theft of equipment is common. Stakeholders, including a number of community leaders from northern Mali, claimed that agreements between elements within the Coordination des Mouvements de l’Azawad and JNIM had resulted in a degree of stability in parts of Kidal and Gao regions, including around ASGM sites, which the armed groups protect and tax.34

The reach of armed groups

As cyanide-based gold extraction becomes more prevalent throughout Burkina Faso and Mali, it is important to consider how it might impact both countries’ ASGM sectors and security. The gold sites, creating demand fed by networks that smuggle cyanide and mercury, are providing livelihoods while also increasing competition for resources. Jihadist groups may seek to control these new sites or benefit from sentiments of insecurity and disenfranchisement, which could result from the social upheaval that comes with rapid paradigm shifts in local economies.

The environmental and health risks associated with cyanide are multiplied when it is used on ore that has already been processed with mercury. Contamination from mercury and cyanide used in ASGM can damage agricultural livelihoods, exacerbating tensions within communities and even sparking conflict, as has already been reported in the Kayes region.35

Concerns over these risks may lead to government closures of certain sites and there have already been bans on the use of cyanide.36 These types of prohibitionist policies may provide opportunities for jihadist groups, who may push the state out of certain areas and win over local populations by allowing them to mine areas that were previously off limits, as they have already done in parts of northern and eastern Burkina Faso.37 In other contexts, jihadist groups have restricted workers’ access to mines so as to limit the number of outsiders arriving in the area, ensuring that only locals can profit from the activity.38

Better monitoring and regulation of cyanide throughout the region is therefore needed not only to mitigate the negative impact that threatens the health and livelihoods of entire communities, but also because the use of cyanide has the potential to upend social arrangements, supply chains and financial dynamics in regions already beset by challenges to stability and human security. Prohibition-based approaches should be carefully considered and, if adopted, partnered with awareness-raising campaigns around the harms of cyanide use, as the Malian government did in 2019.39

A gold mine shaft in Mali.

© Amadou Keita/Afrikimages Agency/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Notes

-

Interviews with researchers and key stakeholders in Mali and Burkina Faso, September 2021. International Crisis Group, Getting a Grip on Central Sahel’s Gold Rush, 13 November 2019, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/burkina-faso/282-reprendre-en-main-la-ruee-vers-lor-au-sahel-central. ↩

-

Flavia Olivieri, Artisanal and small-scale mining in Africa, the environmental and human costs of a vital livelihood source, Lifegate, 29 November 2019, https://www.lifegate.com/artisanal-small-scale-mining-africa; Niladri Basu et al, Integrated assessment of artisanal and small-scale gold mining in Ghana, Part 1: Human health review, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12, 5, 5143–5176; Richard Takyi et al., Socio-ecological analysis of artisanal gold mining in West Africa: A case study of Ghana, Journal of Sustainable Mining, 20, 3; Global trends in artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM): A review of key numbers and issues, Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals, and Sustainable Development, 2018. ↩

-

Cristiano Lanzano and Luigi Arnadli di Balme, Who owns the mud? Valuable leftovers, sociotechnical innovation and changing relations of production in artisanal gold mining (Burking Faso), Journal of Agrarian Change, 15 February 2021, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/joac.12412. ↩

-

Interviews with local researchers in Mali and Burkina Faso, September 2021. ↩

-

UN Security Council, Final report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to Security Council resolution 2374 (2017) on Mali and renewed to resolution 2484 (2019), S/2020/785/Rev.1, 7 August 2020; International Crisis Group, Getting a grip on central Sahel’s gold rush, 13 November 2019, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/burkina-faso/282-reprendre-en-main-la-ruee-vers-lor-au-sahel-central. ↩

-

David Lewis and Ryan McNeill, How jihadists struck gold in Africa’s Sahel, Reuters, 22 November 2019, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/gold-africa-islamists/; International Crisis Group, Getting a grip on central Sahel’s gold rush, 13 November 2019, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/burkina-faso/282-reprendre-en-main-la-ruee-vers-lor-au-sahel-central; Nadoun Coulibaly, Islamic State, GSIM, al-Qaeda: The jihadist gold rush in Burkina Faso, The Africa Report, 24 August 2021, https://www.theafricareport.com/120283/islamic-state-gsim-al-qaeda-the-jihadist-gold-rush-in-burkina-faso/; Neil Munshi, Instability in the Sahel: how a jihadi gold rush is fuelling violence in Africa, Financial Times, 26 June 2021. ↩

-

UN Security Council, Final report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to Security Council resolution 2374 (2017) on Mali and renewed to resolution 2484 (2019), S/2020/785/Rev.1, 7 August 2020. ↩

-

Interviews with local researchers in Mali and Burkina Faso; Fahiraman Rodrigue Koné and Nadia Adam, Going for gold in western Mali threatens human security, ISS Today, 8 July 2021, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/going-for-gold-in-western-mali-threatens-human-security. ↩

-

Cristiano Lanzano and Luigi Arnadli di Balme, Who owns the mud? Valuable leftovers, sociotechnical innovation and changing relations of production in artisianal gold mining (Burking Faso), Journal of Agrarian Change, 15 February 2021. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/joac.12412. ↩

-

Interviews with local researchers in Burkina Faso and Mali, September 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with researchers, journalists and law enforcement officials and former security officials in Burkina Faso, September 2021. ↩

-

Interview with government official in Burkina Faso, September 2021. ↩

-

Interview with local researcher in Burkina Faso, September 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with journalists, researchers, current law enforcement officials and a former security official in Burkina Faso, September–October 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interviews with local journalists and local researchers in Burkina Faso, September 2021; North of the countries of the Gulf of Guinea: The new frontier for jihadist groups?, Promediation, Konrad Adenaur Siftung, July 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with local researchers in Burkina Faso, September–October 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with local journalist and local researcher in Burkina Faso, September–October 2021. While some cyanide clearly leaks from industrial mining sites, it is likely that illicitly imported cyanide also enters the region through ports in the coastal countries. ↩

-

Interview with law enforcement official in Burkina Faso, September 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with journalists, a law enforcement official and a former security official in Burkina Faso, September 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with a journalist and a law enforcement official in Burkina Faso, and a researcher in Mali, September–October 2021. ↩

-

Interview with a person previously involved in transporting chemicals in Burkina Faso, September 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with actors in the ASGM sector in Burkina Faso, September–October 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interviews with local journalists and researchers in Mali and Burkina Faso, September 2021. ↩

-

Interview with a researcher studying ASGM dynamics in the Kayes region, Bamako, September 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with local journalists and researchers in Mali and Burkina Faso; law enforcement official in Burkina Faso, security official in Burkina Faso, Spetember 2021; Fahiraman Rodrigue Koné and Nadia Adam, Going for gold in western Mali threatens human security, ISS Today, 8 July 2021, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/going-for-gold-in-western-mali-threatens-human-security. ↩

-

Interview with a researcher studying ASGM dynamics in the Kayes region, Bamako, September 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with current and former security officials in Burkina Faso, September 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with current and former security officials in Burkina Faso, local journalist in Mali, September-October 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with individuals familiar with artisanal gold-mining operations in northern Mali, September–October 2021. This is likely largely due to culture and geography: Kayes and Sikasso have more overlap with Burkina Faso (culturally, ethno-linguistically, etc.). By contrast, northern Mali attracted more actors from Niger and Chad. ↩

-

Interviews with local researchers in Mali, September 2021. ↩

-

Interviews in Mali, September 2021, including multiple contacts within armed groups and those directly familiar with gold mining operations in northern Mali, September–October 2021. ↩

-

Fahiraman Rodrigue Koné and Nadia Adam, How western Mali could become a gold mine for terrorists, ISS Today, 1 April 2021, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/how-western-mali-could-become-a-gold-mine-for-terrorists. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

David Lewis and Ryan McNeill, How jihadists struck gold in Africa’s Sahel, Reuters, 22 November 2019, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/gold-africa-islamists/; International Crisis Group, Getting a grip on central Sahel’s gold rush, 13 November 2019, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/burkina-faso/282-reprendre-en-main-la-ruee-vers-lor-au-sahel-central; Fahiraman Rodrigue Koné and Nadia Adam, How western Mali could become a gold mine for terrorists, ISS Today, 1 April 2021, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/how-western-mali-could-become-a-gold-mine-for-terrorists. ↩

-

Interviews in Mali, including with two individuals who had visited sites in which jihadists restricted mines to outsiders, September 2021. ↩

-

Boris Ngounou, Mali: Government leads campaign against cyanide use in gold panning, Afrik21, 20 September 2019, https://www.afrik21.africa/en/14216-2/. ↩