Chad’s largest goldfield, Kouri Bougoudi, is central to regional stabilization efforts.

In April 2021, rebels calling themselves the Front pour l’alternance et la concorde au Tchad (FACT) entered Chad through its northern border with Libya and carried out the most serious rebel incursion into the country since 2008. The ensuing political turmoil, including the death of the then president, Idriss Déby, not only raised questions about the future of Chad’s political system, but also highlighted the extent to which northern Chad remains a key part of the volatile regional security dynamics that will shape the country’s future.

The Kouri Bougoudi goldfield, straddling Chad’s northern border with Libya, is an area with a concentration of illicit markets and armed criminal actors, which have contributed to regional instability.1 The area experiences regular outbreaks of violence due to deep-rooted sources of tensions between local actors, political grievances and competition over resources.2

At the same time, gold mining in Kouri Bougoudi also provides essential livelihoods and economic opportunities for local populations in an otherwise marginal and impoverished region. In a context where northern Chad and its cross-border areas with Niger and Libya face further destabilization following the return of rebel and mercenary groups from Libya in the wake of the October 2020 peace accords,3 artisanal gold mining has the potential to offer alternatives to criminal activity and armed mobilization. The formation of a new transitional government in Chad, following the death of Déby in April 2021, could provide an opportunity to renew stabilization efforts in the Tibesti region by adopting sustainable efforts to regulate gold mining and moving away from purely securitized approaches to managing the area.

Lying at the heart of several overlapping regional criminal economies, Kouri Bougoudi not only represents a potential powder keg for the region, but also highlights the extent to which effective efforts to stabilize northern Chad will not only have to account for complex criminal interests, but also address long-standing grievances and expectations of local communities. Engagement that fails to account for these dynamics only risks creating new pockets of instability both at the national level and throughout the subregion.

Illicit markets thrive in Kouri Bougoudi

View of Kouri 17, one of the main gold sites.

Photo: GI-TOC

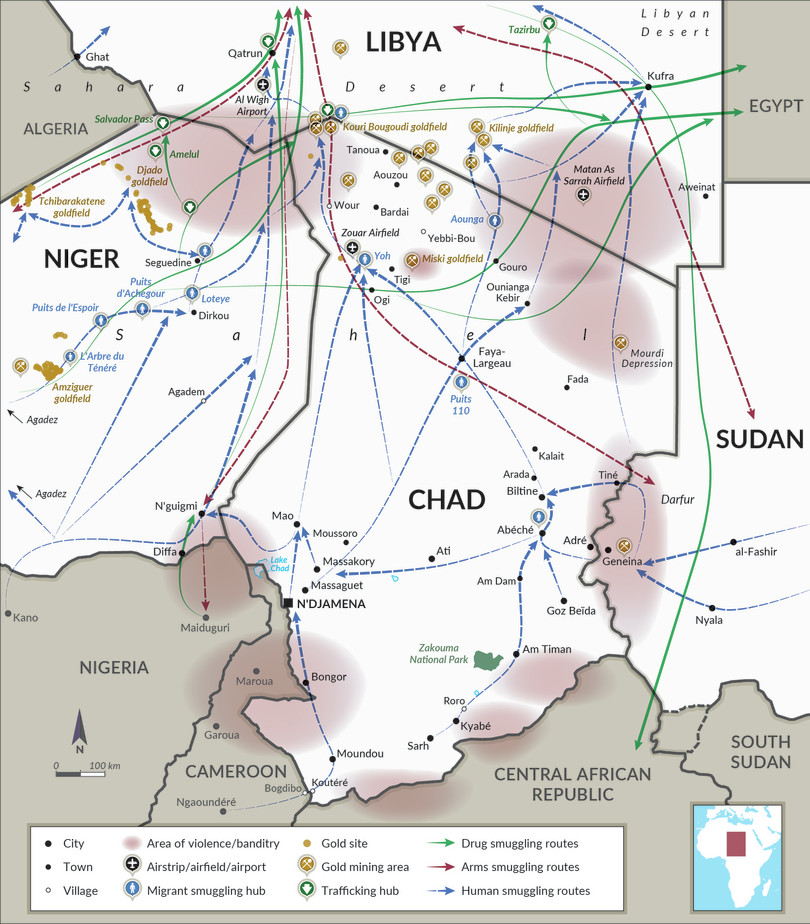

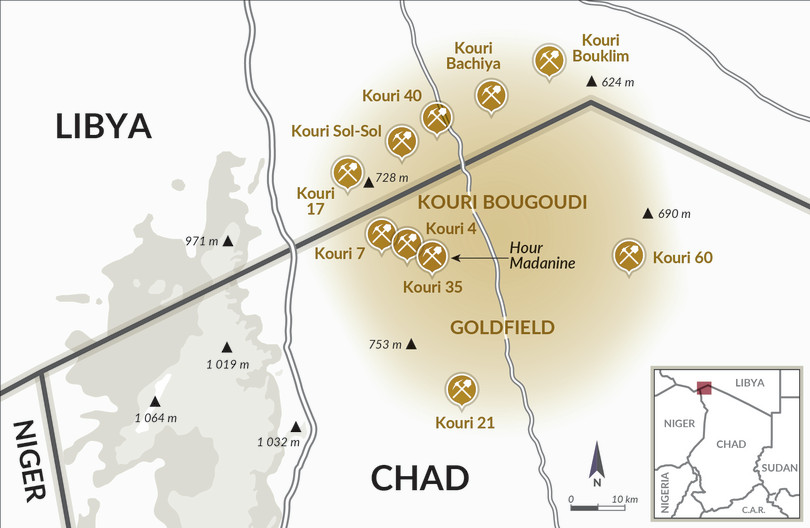

The discovery of gold deposits in northern Chad in 2012 triggered a rush of Chadian and foreign prospectors.4 Kouri Bougoudi is the largest goldfield in northern Chad, with mining sites straddling the Libyan border. Now covering an area of approximately 300 km2, the goldfield at its peak hosted 40 000 gold miners, migrants and others.5 Kouri Bougoudi is also a major regional hub for polycriminal armed groups involved in the smuggling of fuel and food staples, drug trafficking, arms trafficking and armed banditry.6

Artisanal gold mining is officially prohibited in Chad, but its lucrative nature and weaknesses in imposing the government ban in Kouri Bougoudi have made the goldfield a magnet for miners and traders from across the region. Traders buy extracted gold from miners and site ‘owners’ before selling it through various channels. Most gold from Kouri Bougoudi is either transported south to N’Djamena before being exported, or it is sold in Libya. Gold is also used as currency on the goldfield and can change hands in commercial transactions for the purchase of essential supplies, including food, water and equipment,7 or illicit commodities (it has been reported that gold is used to procure drugs and weapons).8

Figure 1 Gold mining areas in Chad, together with regional smuggling and trafficking routes.

Kouri Bougoudi is also a transit point for human smuggling, with migrants travelling to northern Chad in search of economic opportunities before continuing their journey to Libya or Europe. The discovery of gold in the Tibesti region increased Chad’s popularity among migrants both as a destination and transit country. The area has a particular pull for poor migrants aiming to make some money on their journey north. Chad’s role as a migrant transit country accelerated after 2016, when anti-smuggling campaigns launched in Niger and Sudan meant some of the northbound flows were displaced through the country.9

However, lack of regulation or law enforcement in goldfields such as Kouri Bougoudi puts migrants at risk of human trafficking, particularly those who travel on credit to work the goldfields.10 Many migrant smugglers have taken on the role of mine recruiters across the country, offering prospective miners the option to travel on credit. The smugglers are then paid by the gold site owners, who employ the miners in a form of indentured labour, under which the miners must first repay their costs of recruitment before they start earning a wage. The debts owed by migrants for the smuggling are usually around FCFA 300 000 (about €460).11 Such labour agreements often turn into exploitation as workers change hands between gold site owners.12 One young man from Kyabé, in southern Chad, explained how his experience in gold mining in early 2021 had turned sour:

I travelled on credit and had to work for a long time to pay off my debt. The working conditions are very difficult, and our bosses have no mercy. They confiscate all the gold we find, saying it is to pay off our transport, or our food and water, or equipment. In the end, we have nothing left, and sometimes we changed bosses without our consent. The repayment of travel debts can go up to double or triple the [initial] amount. There is no freedom for gold miners and attempts to escape expose them to the anger and reprisals of the bosses.

Organized crime actors operating at the goldfield have also invested in drug trafficking,13 fuelled in part by demand from a growing local consumption market.14 Drugs most commonly consumed there are cannabis and Tramadol,15 their consumption primarily palliative as most users seek to prevent or counter the effects of the gruelling working conditions.16

According to a truck-driver operating between Abéché and Kouri Bougoudi: ‘All [kinds of] drugs are consumed here. Drugs are used on a daily basis and at high frequency, for different reasons. In my opinion, drugs mobilize and motivate people [to work] in the mines. Drugs are visible everywhere and there are many consumers.’17

Kouri Bougoudi also lies at the heart of regional arms trafficking operations, fuelled in part by the proliferation of small arms that followed the collapse of the Qaddafi regime in Libya in 2011.18 Weapons and ammunition from Libya are brought there along clandestine routes through southern Libya via Um Alaraneb, Gatrun, Domozo and Emi Madama. At the goldfield, arms traffickers run operations from locations such as Hour Madanine, a notorious marketplace for drugs and arms trafficking.19 The weapons supply local, regional and international markets, including Chad’s neighbouring countries, notably Sudan and Niger.20

Demand for weapons among criminal networks and the gold mining community has also developed at the goldfield itself in response to rising insecurity and criminality, in the process exacerbating the pre-existing conditions of insecurity and violence,21 with disputes often resolved using armed force and coercion. According to one contact, murder has become a daily occurrence in some of the most dangerous areas of the goldfield, such as Hour Madanine.22

Timeline of key events in Kouri Bougoudi

Challenges and opportunities for stabilization in Kouri Bougoudi

Kouri 17 market, a key exchange point supplying Kouri Bougoudi goldfield with food staples, water, goods and equipment from Libya.

Photo: GI-TOC

This convergence of illicit activities in Kouri Bougoudi is strongly linked to instability and conflict dynamics both locally and regionally.

In the gold mining communities, unregulated and illicit activities have fuelled competition over resources and intercommunal conflict, as well as tensions between local actors and national authorities.23 The community in Kouri Bougoudi is composed mainly of local Chadian and Libyan Tebu, but also communities from eastern and southern Chad and Darfur, including Zaghawa and Arab ethnic groups.24 Mass arrivals of prospectors from other regions following the discovery of gold at Kouri Bougoudi have led to outbreaks of intercommunal violence, triggered by competition over mining operations, but often rooted in long-standing hostilities between ethnic groups.25 The gold rush, and the response of national authorities, also exacerbated tensions between communities and the Chadian authorities.26 The Chadian military, for example, has been accused of colluding with certain gold prospectors in Kouri Bougoudi with whom they share ethnic affinities.27

Here, the gold mining communities have developed their own conflict management mechanisms to mitigate tensions and reduce violence. Each community, for example, has representatives who play a central role in regulating relations in the absence of any formal authority or law enforcement on the part of the state. These representatives act as mediators in the event of disputes between gold miners, and can even authorize or coordinate retaliation or de-escalation in the event of inter-community disputes. Although these mechanisms remain weak and violent clashes still happen, they represent a potential starting point for designing more formal, sustainable, locally owned regulatory frameworks that draw on the experience and authority of community leaders.

Figure 2 Main gold sites in the Kouri Bougoudi goldfield, northern Chad.

Gold mining also provides livelihoods for youths from Chad, Libya and Sudan in a context where formal economic opportunities are scarce. This includes not only direct employment in gold mining, but also opportunities for jobs in the ancillary economies that develop around and are sustained by gold mines. A prosperous market supplying food, water, equipment and other necessities to the gold mining community has boosted economies locally and in other cities, such as Abéché.28 Sustaining such economic conditions is therefore an important factor in stabilizing the area, providing opportunities for those who may otherwise join armed opposition groups or turn to banditry for an income.

Here, the policy approach N’Djamena adopts towards artisanal gold mining will be crucial in the success of regional stabilization efforts. Revenue from gold mining in Kouri Bougoudi has flowed to Libya-based Chadian rebels who share community and political ties with groups involved in the goldfield. Seeking to reduce the capacity of the rebel groups to draw revenues – and recruits – from the goldfield, the Chadian government has made successive attempts in the past to stop artisanal gold mining activity. It has obstructed travel to the goldfields, forcibly expulsed gold miners, destroyed equipment, closed borders and obstructed water supplies.29 The crackdowns on Kouri Bougoudi intensified in 2018 and 2019,30 and in October 2020 the Chadian government announced the closure of illegal gold mining sites across the country and the intent to evacuate all miners.31 However, no concrete steps were taken to implement these measures, and activity in Kouri Bougoudi quickly resumed after miners had temporarily fled.32

The government’s crackdowns on gold mining have not only been unsuccessful, but counterproductive. They have also intensified the regional dynamics of instability33 by depriving local communities of essential livelihoods, fuelling tensions between local populations and national authorities, and reinforcing perceptions that the region’s lack of infrastructure, poor access to services and weak representation within national structures is the result of neglect by national authorities.34 This has fuelled recruitment by armed groups.35 The government’s over-reliance on security-based approaches to stabilizing the region has spawned mutual distrust, as local communities see these tactics as a bid by the government to gain control over a lucrative extraction industry.36

Promisingly, however, there are some indications that Chad’s Comité Militaire de Transition (Military Transitional Council), formed in the wake of Déby’s death, may adopt a slightly different approach. The Council has focused on restricting access to northern Chad’s goldfields by enforcing strict controls over human smuggling routes to northern Chad, rather than attempting further moves to evict gold miners from the goldfields.

Furthermore, in parallel to the Council’s efforts to build a national dialogue process through consultations with the leaderships of opposition groups,37 the government has made discreet overtures with northern Chad stakeholders. Former president Goukouni Weddeye, now head of a technical committee in charge of preparing the participation of rebel groups in the national dialogue, for example, visited Miski in October 2021 to discuss the situation with local leaders.38 Despite contradictory reports on the outcomes of the mission, the visit can be interpreted as a positive step in appeasing tensions and improving relations between national and local authorities.

Designing sustainable and fair policies to regulate gold mining, ones that are founded on dialogue and consultation with local communities, could reduce local conflicts and address deep-rooted grievances, which contribute to local and regional insecurity. Combined with a credible and inclusive disarmament, demobilization and reintegration programme, the regularization of gold mining would help prevent recruitment of people into armed groups and provide legal alternative livelihoods for many young Chadians, who may otherwise turn to organized crime for sustenance.39

Failure to account for and integrate these economic, political and social realities, including those in the criminal space, into Chad’s approach to illicit gold mining risks further alienating local communities, and means armed groups and criminal networks would capitalize on local grievances and lack of state presence and legitimacy in the region. Heightened risks of further incursions by Chadian rebel groups, whose position in Libya has been threatened by political developments, and rising insecurity in the cross-border regions of Chad, Niger and Libya constitute imminent threats to stability in Chad and the greater Sahel region.

Kouri Bougoudi’s position at the heart of these dynamics should therefore be taken into account by national authorities, neighbouring states and international partners in stabilization efforts.

Notes

-

Mark Micallef, Raouf Farrah, Alexandre Bish and Victor Tanner, After the storm - Organized crime across the Sahel-Sahara following upheaval in Libya and Mali, GI-TOC, November 2019, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/After_the_storm_GI-TOC.pdf, pp 67–73. ↩

-

Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi, Tubu trouble: State and statelessness in the Chad–Sudan–Libya triangle, Small Arms Survey, July 2017, https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/sites/default/files/resources/SAS-CAR-WP43-Chad-Sudan-Libya.pdf, pp 70–74. ↩

-

Alexandre Bish, Soldiers of fortune: The future of Chadian fighters after the Libyan ceasefire, GI-TOC, November 2021. ↩

-

Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi, Tubu trouble: State and statelessness in the Chad–Sudan–Libya triangle, Small Arms Survey, July 2017, p 82, https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/sites/default/files/resources/SAS-CAR-WP43-Chad-Sudan-Libya.pdf. ↩

-

Mark Micallef, Rupert Horsley and Alexandre Bish, The human conveyor belt broken – assessing the collapse of the human-smuggling industry in Libya and the central Sahel, GI-TOC, March 2019, p 68, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Global-Initiative-Human-Conveyor-Belt-Broken_March-2019.pdf. ↩

-

following upheaval in Libya and Mali, GI-TOC, November 2019, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/After_the_storm_GI-TOC.pdf, p 72. ↩

-

Ibid., p 76. ↩

-

Interviews with drivers and traders in Kouri Bougoudi, November 2020 and September 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Chad: des associations alertent sur le phénomène grandissant de la traite des personnes, RFI, 14 September 2021, https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20210914-tchad-des-associations-alertent-sur-le-ph%C3%A9nom%C3%A8ne-grandissant-de-la-traite-des-personnes. ↩

-

Mark Micallef et al, Conflict, coping and covid: Changing human smuggling and trafficking dynamics in North Africa and the Sahel in 2019 and 2020, GI-TOC, April 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GI-TOC-Changing-human-smuggling-and-trafficking-dynamics-in-North-Africa-and-the-Sahel-in-2019-and-2020.pdf, p 86. ↩

-

Interviews with returned migrants in southern Chad, February 2021. ↩

-

The drugs trade is facilitated by Kouri Bougoudi’s position at the crossroads between Chad, Niger and Libya, as well as its proximity to trafficking hubs and its remote location beyond the reach of state authorities. ↩

-

Mark Micallef, Raouf Farrah, Alex Bish and Victor Tanner, After the storm – Organized crime across the Sahel-Sahara following upheaval in Libya and Mali, GI-TOC, November 2019, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/After_the_storm_GI-TOC.pdf, p 92. ↩

-

Interview with gold site owner in Kouri Bougoudi, February 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with gold miners and traders in Kouri Bougoudi, December 2020; Drug consumption among goldmining communities in Niger is also mentioned in Emmanuel Grégoire and Laurent Gagnol, Ruées vers l’or au Sahara: l’orpaillage dans le désert du Ténéré et le massif de l’Aïr (Niger), EchoGéo, Sur le Vif, http://journals.openedition.org/echogeo/14933 DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.14933. ↩

-

Interview with a passeur (a local term referring to smugglers involved in the transport of migrants) in Abéché, November 2020. ↩

-

Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi, Tubu trouble: State and statelessness in the Chad–Sudan–Libya triangle, Small Arms Survey, July 2017, https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/sites/default/files/resources/SAS-CAR-WP43-Chad-Sudan-Libya.pdf , p 8. ↩

-

Interviews with gold miners in Kouri Bougoudi, September 2021; Alexandre Bish, Soldiers of fortune: The future of Chadian fighters after the Libyan ceasefire, GI-TOC, November 2021. ↩

-

Oluwole Ojewale, Arms trafficking – Déby’s death accelerates illicit arms flows across Central Africa, ENACT Observer, 30 August 2021, https://enactafrica.org/enact-observer/debys-death-accelerates-illicit-arms-flows-across-central-africa; Interviews with smugglers in Kouri Bougoudi, October 2021; Alexandre Bish, Soldiers of fortune: The future of Chadian fighters after the Libyan ceasefire, GI-TOC, November 2021. ↩

-

Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi, Tubu trouble: State and statelessness in the Chad–Sudan–Libya triangle, Small Arms Survey, July 2017, https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/sites/default/files/resources/SAS-CAR-WP43-Chad-Sudan-Libya.pdf, p 84. ↩

-

Interview with gold miner in Kouri Bougoudi, September 2021, see also Alexandre Bish, Soldiers of fortune: The future of Chadian fighters after the Libyan ceasefire, GI-TOC, November 2021. ↩

-

Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi, Lost in trans-nation: Tubu and other armed groups and smugglers along Libya’s southern border, Small Arms Survey, December 2018, pp 70–74. ↩

-

Mark Micallef, Raouf Farrah, Alex Bish and Victor Tanner, After the storm – Organized crime across the Sahel-Sahara following upheaval in Libya and Mali, GI-TOC, November 2019, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/After_the_storm_GI-TOC.pdf, p 68. ↩

-

Ibid., p 68. For further discussion of conflicts around gold mining in the Tibesti, see Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi Tubu trouble: State and statelessness in the Chad–Sudan–Libya triangle, Small Arms Survey, July 2017, https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/sites/default/files/resources/SAS-CAR-WP43-Chad-Sudan-Libya.pdf, pp 83–92. ↩

-

In response to the threat of foreign gold miners and attempts by the government to exert control over goldfields, local Tebu in Miski reactivated customary self-defence groups named ‘wangada’, aimed at monitoring gold mining and protecting the interests of local communities. Wangadas have also been activated occasionally in Kouri Bougoudi, notably in 2015 during the ‘battle of Kouri Bougoudi’. See Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi, Tubu trouble: State and statelessness in the Chad–Sudan–Libya triangle, Small Arms Survey, July 2017, https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/sites/default/files/resources/SAS-CAR-WP43-Chad-Sudan-Libya.pdf, p 96. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Mark Micallef, Raouf Farrah, Alex Bish and Victor Tanner, After the storm – Organized crime across the Sahel-Sahara following upheaval in Libya and Mali, GI-TOC, November 2019, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/After_the_storm_GI-TOC.pdf, p 72. ↩

-

Travel to northern Chad’s goldfields is prohibited, with military units deployed at transit points for human smuggling routes, such as Mao, Moussoro and Faya-Largeau. The military presence increased significantly after the FACT incursion in April and contributed to a decline in human smuggling operations to northern Chad in recent months; see https://www.alwihdainfo.com/Tchad-des-orpailleurs-clandestins-presentes-a-Abeche_a103844.html. ↩

-

Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi, Lost in trans-nation: Tubu and other armed groups and smugglers along Libya’s southern Border, Small Arms Survey, December 2018, pp70–74; Mark Micallef, Rupert Horsley and Alexandre Bish, The human conveyor belt broken – assessing the collapse of the human-smuggling industry in Libya and the central Sahel, GI-TOC, March 2019, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Global-Initiative-Human-Conveyor-Belt-Broken_March-2019.pdf, pp 76–77; Chevrillon-Guibert Raphaëlle, Gagnol Laurent, Magrin Géraud, « Les ruées vers l’or au Sahara et au nord du Sahel. Ferment de crise ou stabilisateur ? », Hérodote, 2019/1 (N° 172), pp 193–215. DOI : 10.3917/her.172.0193. https://www.cairn.info/revue-herodote-2019-1-page-193.ht, p 200. See also L’armée va expulser «tous les orpailleurs» de Kouri Bougri au Tchad, VOA Afrique, 16 August 2018, https://www.dropbox.com/home/GI_TOC%20Team%20Folder/Communications/Reports%20to%20launch%20and%20PR/Launching%20Station/AW/AW%20Monitor%20report/layout/final; L’orpaillage clandestin visé au Tchad, VOA Afrique, 20 August 2018, https://www.voaafrique.com/a/l-orpaillage-clandestin-vis%C3%A9-au-tchad/4536195.html; Tchad : des milliers d’orpailleurs contraints de quitter Kouri-Bougoudi, Al Wihda Info, 6 March 2019, https://www.alwihdainfo.com/Tchad-des-milliers-d-orpailleurs-contraints-de-quitter-Kouri-Bougoudi_a71192.html. ↩

-

See Tchad : le gouvernement ordonne la fermeture de tous les sites illégaux d’orpaillage, Al Wihda Info, 8 October 2020, https://www.alwihdainfo.com/Tchad-le-gouvernement-ordonne-la-fermeture-de-tous-les-sites-illegaux-d-orpaillage_a94937.html; Ndalet Pohol, Mines: Le Tchad Suspend “l’orpaillage illégal”, Tchad Infos, 8 October 2020, https://tchadinfos.com/tchad/tchad-le-gouvernement-prend-des-mesures-pour-lutter-contre-lexploitation-illegale-de-lor/. ↩

-

Over the past few years, the Chadian government has issued several such announcements targeting goldfields, but the combination of constrained budgets, the Tibesti’s challenging topography and the illicit revenue allegedly earned by some members of the Chadian military from gold mining activity and smuggling have undermined their implementation. Mark Micallef et al, Conflict, coping and covid: Changing human smuggling and trafficking dynamics in North Africa and the Sahel in 2019 and 2020, GI-TOC, April 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GI-TOC-Changing-human-smuggling-and-trafficking-dynamics-in-North-Africa-and-the-Sahel-in-2019-and-2020.pdf, p 82. ↩

-

Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi Tubu trouble: State and statelessness in the Chad–Sudan–Libya triangle, Small Arms Survey, July 2017, pp 98–99; Alexandre Bish, Soldiers of fortune: The future of Chadian fighters after the Libyan ceasefire, GI-TOC, November 2021. ↩

-

Madjiasra Nako, « Tchad : quand la ruée vers l’or provoque des tensions intercommunautaires», Jeune Afrique, 15 August 2014, https://www.jeuneafrique.com/47036/societe/tchad-quand-la-ru-e-vers-l-or-provoque-des-tensions-intercommunautaires/. ↩

-

Alexandre Bish, Soldiers of fortune: The future of Chadian fighters after the Libyan ceasefire, GI-TOC, November 2021. ↩

-

The pitfalls of such policies are well illustrated by the situation in Miski. Following an attack by the Libya-based Council of Military Command for the Salvation of the Republic (Conseil de Commandement Militaire pour le Salut de la République – CCMSR) on a Chadian army unit in the Kouri Bougoudi area in August 2018, the Chadian government launched a major retaliation campaign aimed at the Tibesti goldfields. Despite the lack of rebel presence in Miski, where the Tebu community do not share ties to the CCMSR, the Chadian army attacked the town using air strikes, a ground offensive and a strict blockade. Although the government justified the offensive in security terms, it is widely understood to have been an attempt to pave the way for industrial gold extraction in the area. This led to violent clashes between the Chadian army and local self-defence groups, which had initially been formed by local communities to expel ‘foreign’ gold miners. See Crisis Group, « Tchad : sortir de la confrontation à Miski », Crisis Group Africa Report N°274, 17 May 2019, https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront.net/274-tchad-sortir-de-la-confrontation_0.pdf, p 11; Mark Micallef, Raouf Farrah, Alexandre Bish and Victor Tanner, After the storm – Organized crime across the Sahel-Sahara following upheaval in Libya and Mali, GI-TOC, November 2019, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/After_the_storm_GI-TOC.pdf, p 77. ↩

-

Transition au Tchad: deux délégations du Comité technique du dialogue en Égypte et en France, RFI, 20 October 2021, https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20211020-transition-au-tchad-deux-d%C3%A9l%C3%A9gations-du-comit%C3%A9-technique-du-dialogue-en-egypte-et-en-france. ↩

-

#TCHAD #Tibesti : Tension à Miski pour la visite du général Oki Dagache et l’ex-président Goukouni Weddeye, Le Tchadanthropus, 11 October 2021, https://www.letchadanthropus-tribune.com/tchad-tibesti-tension-a-miski-pour-la-visite-du-general-oki-dagache-et-lex-president-goukouni-weddeye/. ↩

-

Alexandre Bish, Soldiers of fortune: The future of Chadian fighters after the Libyan ceasefire, GI-TOC, November 2021. ↩