Football hooliganism in the Western Balkans reveals links between hooliganism, politics, violence and crime, although these vary across the region.

‘Today is Sunday’, a football match day. That is how an artist celebrates his favourite football club, FC Partizan, with graffiti in Belgrade, quoting the popular Serbian poet and football fan Dusko Radovic. The quote refers to the day when football matches are generally played and the mural recalls feelings of respect, resilience, loyalty and integrity.

A mural in Belgrade with the message ‘Today is Sunday (match day)’ celebrates the Serbian poet and FC Partizan fan Dusko Radovic.

Photo: Bahrudin Bandic

But in the Western Balkans, football Sundays occasionally show the opposite values. Fans chant racist and nationalist slogans, while supporters of rival teams brawl with each other or the police. This is not a problem unique to the Balkans, but as shown by a new GI-TOC report, in some cases there are destabilizing links between football hooligans, politics and organized crime.1

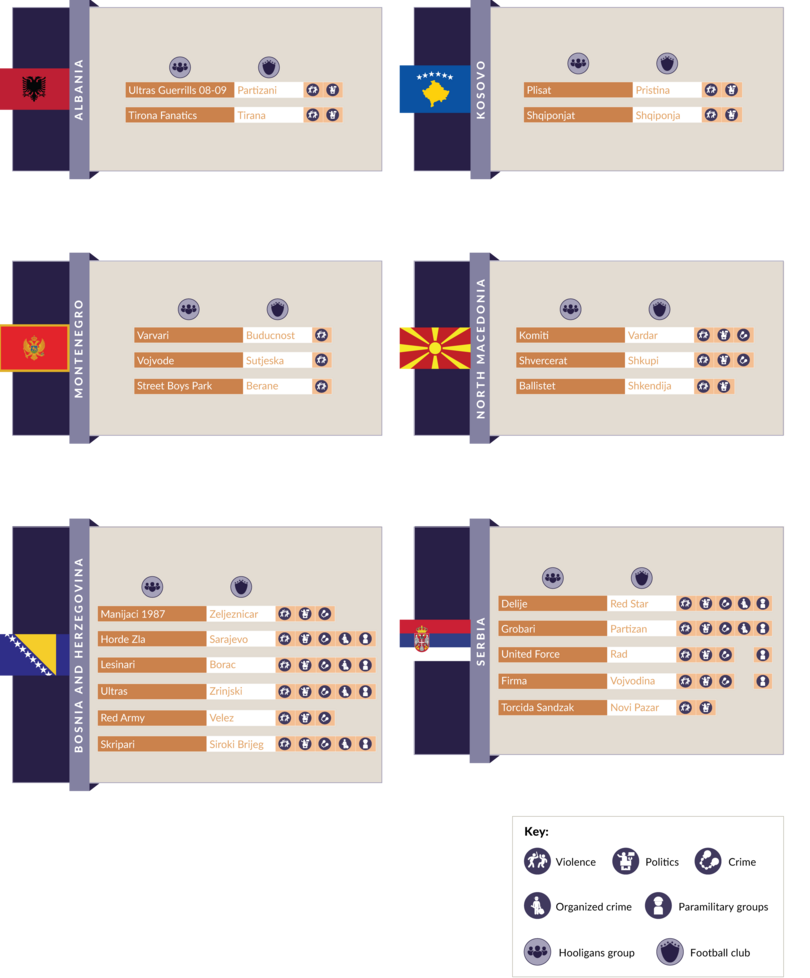

Our research analyzed 122 fan groups of football clubs in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia and identified 78 groups whose followers can be considered ‘ultras’, namely passionate and well-organized associations of football fans. Of these 78 hard-core fan groups, 21 can be considered hooligans that pose a serious security risk due not only to their propensity for violence, but also for their links to politics and organized crime.

Figure 1 Hooligan groups in the Western Balkans linked with violence, politics and crime.

Source: Saša Đorđević and Ruggero Scaturro, Dangerous games: Football hooliganism, politics and organized crime in the Western Balkans, GI-TOC, June 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Football-hooliganism-politics-and-organized-crime-in-the-Western-Balkans-GITOC-SEEObs.pdf

Violence

Hooligan groups in the Western Balkans are renowned for the use of violence, with a particular critical situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia and Serbia. Football-related violence often presents strong nationalistic undertones, with fans singing national anthems, displaying fascist symbols and glorifying war heroes.2

Some hooligans have also reportedly joined paramilitary groups, indicating the existence of a nexus between the use of violence and political extremism. For example, members of the Serbian United Force (supporting FC Rad from Belgrade), Firma (supporting FC Vojvodina from Novi Sad)3 and ultras based in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina (supporting FC Zrinjski), fought in the conflicts in Ukraine and Syria.4 Their actions are often displayed and praised on social media platforms.

A mural dedicated to Zelimir Vidovic Keli, former player of FC Sarajevo and the Yugoslav national football team. He died at war during the 1990s.

Photo: Bahrudin Bandic

Even lockdowns did not stop the violence. The COVID-19 pandemic emptied football stadiums but didn’t prevent hooligan-led violence. In April 2021, antagonism between Mostar-based hooligans divided around ethnic identity resulted in vandalism.5 In the same month, concerns about tensions between Red Star and Partizan supporters caused the US Department of State to issue a red alert about possible violence in Belgrade.6

Politics

The GI-TOC report gives examples of the deployment of football hooligans for political ends in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia and Serbia. Political parties use hooligan groups to promote their agenda with chants and banners inside the stadiums and stoke ethnic or political tension before elections. They can also act as a ‘rent-a-mob’ to provide muscle at demonstrations. As one fan in Banja Luka in Bosnia and Herzegovina explained, football hooligans ‘act as a private army to politicians’.7

In exchange for violent support, politicians grant leaders of hooligan groups lucrative business opportunities and ensure that they receive political protection in case of investigations or prosecution.

Social media use

Ultras in the Western Balkans use social media to express feelings, values or beliefs; share and comment on content; carry out group-related business such as identity-promotion activities; and recruit and mobilize supporters for particular gatherings or events.

Ultras and hooligan groups in the Western Balkans typically use Facebook and Instagram.8 There are both official and unofficial profiles. Official accounts usually publish news, promote the fan group and club and sell merchandise online. In contrast, many unofficial and private accounts serve as tools for the group’s functioning or internal communication.9

Unofficial groups are primarily closed to the public. Only trusted individuals can become part of them. They are attractive to both young generations and older nostalgics. However, it is easier for youths to join. Sometimes, it is enough to share posts and have mutual friendships with the account administrators. When older users want to join groups, the administrators first check whether they might have connections with the police.10

Crime

The nexus between hooligans and crime is particularly strong in Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia. In Serbia, it has reached the level of serious organized crime.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, some Ultra members, such as Lesinari, Horde Zla and Škripari, commit petty crimes but are also part of organized criminal groups involved in drug trafficking and arms smuggling.11 In North Macedonia, Skopje-based hooligan groups Komiti and Svercerat are known to sell drugs and smuggle arms, which helps finance other illicit activities.12

In Serbia, there is a more concerning risk. Members of some hooligan groups engage in serious organized crime, yet they enjoy a fair degree of political protection. The Janjicari, supporters of FC Partizan, have built close ties with state officials (especially police officers) as well as the Kavač clan, an organized crime group from Montenegro specializing in trafficking cocaine from Latin America to Europe.13

In February 2021, Serbian police arrested the leader of Principi (supporting FC Partizan) upon his return from a meeting with the Kavač clan in Montenegro.14 Police arrested over 20 Principi members and charged them with association for criminal purposes, drug trafficking, possession and trafficking in arms and aggravated murder.15

As seen in Figure 2, the level of risk and links between football hooliganism, politics and crime are not uniform across the region; the problem is most acute in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia, while links between hooliganism and crime are absent in Albania and low in Kosovo, North Macedonia and Montenegro.

Figure 2 Level of risk due to strength of links between hooliganism, politics, violence and crime.

Source: Saša Đorđević and Ruggero Scaturro, Dangerous games: Football hooliganism, politics and organized crime in the Western Balkans, GI-TOC, June 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Football-hooliganism-politics-and-organized-crime-in-the-Western-Balkans-GITOC-SEEObs.pdf

This article draws on research from ‘Dangerous games: Football hooliganism, politics and organized crime in the Western Balkans’, a paper by Sasa Djordjevic and Ruggero Scaturro published in June 2022. Available at: https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/hooligans-crime-balkans/.

Notes

-

Saša Đorđević and Ruggero Scaturro, Dangerous games: Football hooliganism, politics and organized crime in the Western Balkans, GI-TOC, June 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/hooligans-crime-balkans/. ↩

-

Interview with a scholar on violent extremism in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 7 May 2021; Nemanja Stevanović, Ultradesničarski simboli na fudbalskim stadionima u Srbiji uprkos zakonskoj zabrani, VOICE, 17 October 2021, https://voice.org.rs/ultradesnicarski-simboli-na-fudbalskim-stadionima-u-srbiji-uprkos-zakonskoj-zabrani/; Marija Arnautović and Mirsad Behram, Fašizam na svom terenu: Ekstremistički pokliči sa bh. stadiona, Radio Slobodna Evropa, 13 November 2020, https://www.slobodnaevropa.org/a/fa%C5%A1izam-na-svom-terenu-ekstremisti%C4%8Dki-pokli%C4%8Di-sa-bh-stadiona/30946282.html; Srbija i nasilje u sportu: Zašto šovinizam pobeđuje sport u Srbiji – ‘problem je uvek u vašoj kući’, BBC na srpskom, 15 October 2021, https://www.bbc.com/serbian/lat/srbija-58928316; Fabio Bego, Do Albanians like Fascism? An Iconographical Investigation on Social Media Material, Modern Diplomacy, 3 January 2020, https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2020/01/03/do-albanians-like-fascism-an-iconographical-investigation-on-social-media-material/. ↩

-

Interview with journalist in Belgrade, Serbia, 5 August 2021. ↩

-

Insajder bez ogranicenja: ‘Sukob oko sistema vrednosti’, Insajder, 16 May 2017, https://insajder.net/sr/sajt/bezogranicenja/4715/. ↩

-

U Mostaru desetoro privedeno zbog tuce huligana, Danas, 25 April 2021, https://www.danas.rs/svet/u-mostaru-desetoro-privedeno-zbog-tuce-huligana/; Mirsad Behram and Selma Boracic Mrso, ‘Licilo je na 1993’. Mostar uznemiren posljednjim huliganskim nasiljem, Radio Slobodna Evropa, 26 April 2021, https://www.slobodnaevropa.org/a/incident-u-mostaru-huligani/31223736.html. ↩

-

Security Alert: Belgrade (Serbia), High risk of hooliganism when soccer clubs play on April 7, Overseas Security Advisory Council, Bureau of Diplomatic Security, U.S. Department of State, 6 April 2021, https://www.osac.gov/Country/Serbia/Content/Detail/Report/01aa3735-31c3-480e-85b7-1b4849c094ab. ↩

-

Interview with a Lesinari member in Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 6 May 2021. ↩

-

Interview with a journalist in Belgrade, Serbia, 29 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with a journalist in Belgrade, Serbia, 5 August 2021. ↩

-

Interview with a journalist in Belgrade, Serbia, 29 July 2021. ↩

-

Interview with a Komiti fan in Skopje, North Macedonia, 5 April 2021; Interview with a City Park Boys fan in Skopje, North Macedonia, 5 April 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Stevan Dojčinović et al, Rat balkanskog podzemlja: Ubistva, veze u policiji i u vrhu drzave, KRIK, 5 May 2020, https://www.krik.rs/rat-balkanskog-podzemlja-ubistva-veze-u-policiji-i-u-vrhu-drzave/; Bojana Jovanović and Stevan Dojčinović, Gangsters and hooligans: key players in the Balkan cocaine wars, OCCRP, 5 May 2020, https://www.occrp.org/en/balkan-cocaine-wars/gangsters-and-hooligans-key-players-in-the-balkan-cocaine-wars. ↩

-

Odredjen pritvor osumnjicenima V. Belivuk i drugi, Visi sud u Beogradu, 6 February 2021, https://www.bg.vi.sud.rs/vest/2991/odredjen-pritvor-osumnjicenima-v-belivuk-i-drugi.php. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩