Maritime routes become more popular for trafficking through the Balkans.

The Balkan region is a natural crossroads for trade from Asia and Africa to Europe, and vice versa. Traditionally, the focus on trade in the region has been on land routes. But it is often overlooked that there are a number of sizeable ports along the Adriatic and Ionian coasts, the Aegean and Black seas, as well as along the Danube river.

Much of the infrastructure of these ports suffered with the collapse of communism and wars in Yugoslavia in the 1990s, and later with the financial crisis of 2008. But increased investment, particularly from the European Union and China, is improving port infrastructure in the region, increasing the size and efficiency of container ports, as well as the road and rail links needed to bring goods to various markets. The major seizures of drugs and cigarettes in regional ports over the past few years show that these factors are also making these ports more attractive for smuggling contraband into the Western Balkans.

Increasing amounts of cocaine, heroin and synthetic drugs

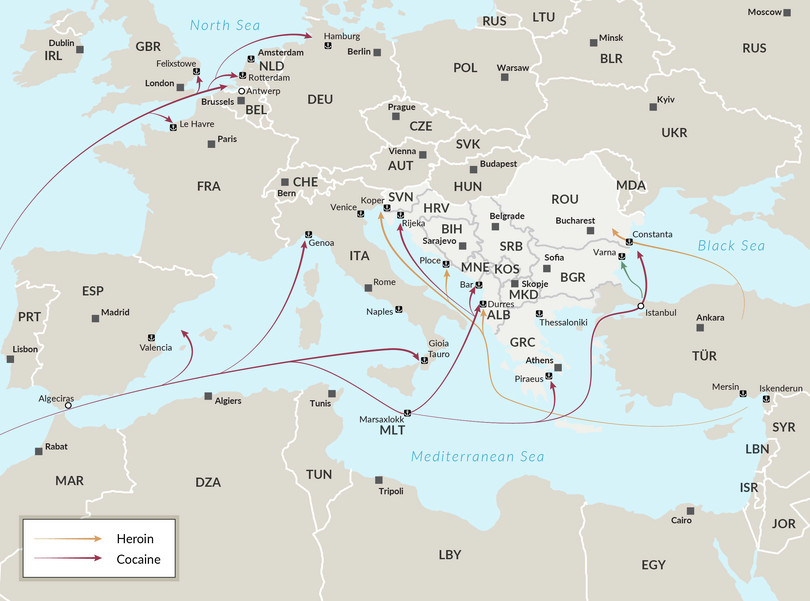

As analyzed in previous GI-TOC research, criminal groups from the Western Balkans are involved in the smuggling of drugs – particularly cocaine – from Latin America to western Europe on container ships and yachts. In south-eastern Europe, the main type of ‘blue crime’ (i.e., the maritime-based criminal economy) is cocaine and heroin trafficking.1

The region’s proximity to large and lucrative consumer markets in western Europe, its links to North Africa and Turkey and increased trade from Latin America and Asia, combined with vulnerabilities linked to corruption, create ideal conditions for criminal networks to engage in such trafficking. To give an idea of the quantities involved, between 2018 and 2021, roughly 8 tonnes of cocaine were seized in Western Balkan ports, with Piraeus (Greece), Durres (Albania) and Constanta (Romania) accounting for half of that total.2 However, cocaine is not the only drug entering the region through ports; heroin and, more recently, synthetic drugs are regularly intercepted in regional ports.3

Figure 1 shows that heroin enters the region through two main ports: Varna (Bulgaria) and Koper (Slovenia). Varna constitutes an additional entry point from the Black Sea to the traditional Balkan route over land to western Europe. As an example, in February 2021, Bulgarian customs officials confiscated more than 400 kilograms of heroin from a ship transporting goods from Iran. The drugs were divided into 487 packages and hidden among asphalt rollers the ship was carrying – a shipment likely too big for the Bulgarian market.4 For its part, Koper is the ideal entry port for networks trying to avoid crossing the Balkans by land. Containers come from Turkey and Iran by circumventing the whole region and are delivered directly at the gates of western Europe. Based on information about drug busts at the port of Koper, it emerges that Slovenian authorities have seized over a tonne of heroin in the past four years.5

Synthetic drugs meant to supply European markets are increasingly being seized in regional ports. Amphetamines from Syria, Sri Lanka and India, headed to Europe or Libya, are concealed in different ways, including in containers of sheets, blankets and towels. Of concern for authorities are Captagon amphetamines, the so-called ‘jihadist’s drug’. For example, in 2019, 23 million Captagon pills were found in three containers that had been shipped from Syria and were on their way to China via Piraeus.6

Figure 1 Illicit flows along the maritime Balkan routes.

Source: Ruggero Scaturro and Walter Kemp, Portholes: Exploring the maritime Balkan routes, GI-TOC, July 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/balkans-maritime-routes-ports-crime/

Blue crime on the Danube: Illicit flows into the heart of Europe?

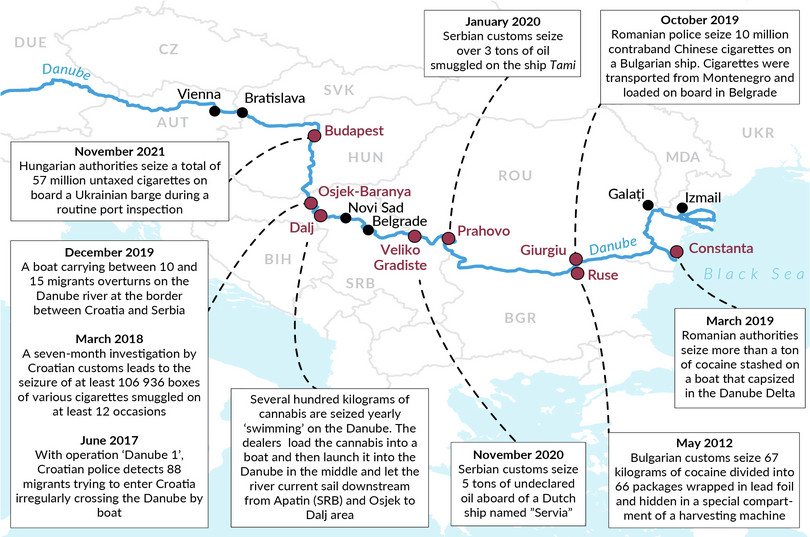

Unlike in commercial seaports, most of the cargo moving along the Danube is stored in bulk and carried on barges, making it difficult to inspect. One would have to poke a metal rod into a pile of, for example, sand or gravel to see if something was hidden under it. Or some of the cargo would have to be unloaded, which is both time consuming and logistically challenging. In November 2021, the Hungarian National Tax and Customs Administration seized a record shipment of 57 million untaxed cigarettes that were hidden in salt on a barge coming from Ukraine.7

Figure 2 shows that the extent of trafficking of goods on barges on the Danube river seems to be underestimated by law enforcement officials, since most major discoveries of contraband have been made by accident.

Figure 2 Examples of smuggling along the Danube.

Source: Ruggero Scaturro and Walter Kemp, Portholes: Exploring the maritime Balkan routes, GI-TOC, July 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/balkans-maritime-routes-ports-crime/

The war in Ukraine could create new opportunities for smuggling of both licit goods (such as fuel) and illicit ones (such as weapons and drugs). Cooperation around the Danube and Black Sea regions therefore deserves urgent attention and closer cooperation between states, using existing bodies such as the Danube Commission, Europol and the Southeast European Law Enforcement Center.

Local and foreign criminal actors

Criminal actors that exploit the maritime Balkan routes can be categorized into four types, applying the classification provided by the GI-TOC’s Global Organized Crime Index: criminal networks, state-embedded actors, mafia-style groups and foreign actors.8 Criminal networks are present in ports such as Koper, Rijeka and Ploce, where cells of what Europol and the media have labelled the ‘Balkan cartel’ operate occasionally. One of the main advantages of this criminal association is the absence of language and cultural barriers among Bosnians, Croats, Montenegrins and Serbs.

By state-embedded actors, the Index refers to criminal actors that operate from within the state’s apparatus. The port of Bar has historically been recognized as the European hub for cigarette smuggling, a trade that has been supported and facilitated by high-ranking officials and political elites. Another example is Varna, where corruption scandals, alleged misuse of funds and allegations of money laundering characterize the recent history of the port administration.

Third, mafia-style groups are criminal groups with a defined leadership and territorial control. In SEE, commercial ports such as Bar, Durres and Rijeka fall into the traditional area of criminal ‘influence’ and coverage of well-defined local mafia-style groups.

Fourth, foreign actors refer to criminal actors operating outside their home country, including diaspora groups that have created roots in other countries over generations. The latter detail is particularly relevant for the Greek ports of Piraeus and Thessaloniki, where ethnic Albanians with Greek passports reportedly control most of the cocaine trade. Depending on the illicit commodity, other examples of foreign actors active along the maritime Balkan routes are Italian criminal groups in Rijeka and Piraeus, Montenegrins and Serbs in Koper, Serbs in Constanta and Serbs and Turks in Varna. Indeed, the latter ports are crime magnets for criminal groups from land-locked countries in the Western Balkans.

Selling cigarettes from the port of Bar

More than 2 billion cigarettes are smuggled through the port of Bar every year, which results in a loss of €300 million in customs and excise tax. As part of its campaign to stop cigarette smuggling, in July 2021 the government of Montenegro prohibited the storage of tobacco products in the port’s free zone. As a result, an entire hangar is full of cigarettes. Since the owners did not come to pick them up by May 2022 (which was the government’s scheduled deadline), customs seized more than 140 000 packs of cigarettes worth over €60 million on the illegal market. The question now is what to do with them.

The Montenegrin government is planning to give the owners one last chance – until September 2022 – to pick up the tobacco products and pay the required state taxes (30 cents for every package of cigarettes, €10 per kilogram of cut tobacco and €10 per kilogram of hookah flavour). At the same time, the government has drafted a law that would enable it to sell the cigarettes and generate €15–20 million in revenue if the owners do not collect the goods and pay the tax by the deadline.

This proposal has generated some criticism from the international community, including the World Health Organization, which has argued that the confiscated cigarettes should be destroyed. They stated that putting seized cigarettes on the market is not in accordance with the Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products, which Montenegro ratified in 2017. They point out that international law should take precedence over national law and that adopting this law would violate this principle and lead to the uncontrolled movement of seized cigarettes.

Paradoxically, while trying to do the right thing and crack down on cigarette smuggling, the government of Montenegro has found itself in hot water.

Focus on the flows

Concerns about maritime trafficking tend to result in a focus on increasing the security of ports. But building higher fences and installing more scanners and cameras are only part of the solution. Trade on container ships is usually transnational. The illicit goods being transported into south-eastern Europe in containers are often travelling long distances from Latin America, North Africa or Asia. Therefore, understanding and disrupting illicit trade that uses licit routes and modalities requires international cooperation. Ports should be seen as links in a chain rather than in isolation.

Governments of the Western Balkans have made great strides in the past 20 years to improve port security in line with the International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code, thanks to international support from organizations such as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and Europol, as well as bilateral assistance. However, the ISPS Code measures that potentially mitigate some of the risks of criminal activity do not focus on the flow of containerized goods, which is where most criminal activity concentrates.9

At the moment, there is insufficient cooperation among security providers within and between ports, for example between customs agencies. This could be improved by creating unified task forces or joint port control units, deploying liaison officers (from neighbouring countries, countries of supply and/or relevant international organizations) and making more effective used of special investigative techniques.

Furthermore, there is a disconnect between those responsible for port security and law enforcement agencies dealing with organized crime. This could be remedied by putting a stronger focus on maritime security in organized crime threat assessments; exchanging information on concealment and interdiction techniques, as well as on criminal groups active along the maritime Balkan route; sharing updates on changes in drug production and supply mechanisms; and providing briefings on trading patterns and how they could affect illicit activity. It would also be useful to have a common database to track seizures, arrests and criminal actors along the maritime Balkan routes.

Even the best security systems will be in vain if there is corruption in a port. Therefore, it is important to have measures that strengthen integrity. Digitalization may reduce the chance of corruption, but computer programmes can be infiltrated to decrease the chance of detecting cargo hidden in containers. And thus far, artificial intelligence has not progressed to the point of replacing experienced customs and law enforcement officials with a ‘nose’ for making threat assessments. In short, technology should be considered as a potential asset to improve port security, but not as a panacea.

This article draws on research from ‘Portholes: Exploring the maritime Balkan routes’, a new GI-TOC study by Ruggero Scaturro and Walter Kemp published in July 2022. Available at: https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/balkans-maritime-routes-ports-crime/.

Notes

-

Walter Kemp, Transnational tentacles: Global hotspots of Western Balkan organized crime, GI-TOC, July 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Transnational-Tentacles-Global-Hotspots-of-Balkan-Organized-Crime-ENGLISH_MRES.pdf; SIPRI, The Black Sea: Engaging in dialogue and combatting nuclear smuggling, https://www.sipri.org/research/conflict-peace-and-security/europe/black-sea-engaging-dialogue-and-combatting-nuclear-smuggling; Ben Crabtree, Black Sea: A rising tide of illicit business?, GI-TOC, 1 April 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/black-sea-illicit-flows. ↩

-

See for instance: Albania seizes 613 kilos of Colombia cocaine, holds two, Reuters, 28 February 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-albania-cocaine-idUSKCN1GC2KY; Romania seizes record 2.5 tons of Colombian cocaine, 5 held, Reuters, 1 July 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-colombia-drugs-romania-idUSKCN0ZH4X1; Hellenic Republic Ministry of Citizen Protection, Κατασχέθηκαν -35- κιλά κοκαΐνης σε εμπορευματοκιβώτιο στο λιμάνι του Πειραιά, 23 December 2020, http://www.astynomia.gr/index.php?option=ozo_content&lang=%27..%27&perform=view&id=99409&Itemid=2565&lang. ↩

-

Interview with an expert on container control and security in SEE, December 2021. ↩

-

Associated Press, Bulgarian prosecutors say heroin found in cargo from Iran, ABC News, 16 February 2021,https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/bulgarian-prosecutors-heroin-found-cargo-iran-75923810. ↩

-

T R, Še pomnite zaseg 300 kg heroina v luki Koper? Tožilstvo spisalo obtožbo, dvojica še vedno na begu, Regional, 10 September 2019, https://www.regionalobala.si/novica/se-pomnite-zaseg-300-kg-heroina-v-luki-koper-tozilstvospisalo-obtozbo-dvojica-se-vedno-na-begu; Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Slovenia, The biggest seizure of heroin in Slovenia result of the cooperation of the Slovene and Hungarian police units and financial administration, 13 November 2019, https://www.policija.si/eng/newsroom/news-archive/101619-the-biggest-seizure-of-heroin-in-slovenia-result-of-the-cooperation-of-the-slovene-and-hungarian-police-units-and-financial-administration-press-release; and R K, V Luki Koper zasegli več kot 200 kilogramov heroina, Siol, 16 June 2021, https://siol.net/novice/slovenija/v-luki-koper-zasegli-vec-kot-200-kilogramov-heroina-554783. ↩

-

Piraeus counterfeit Captagon amphetamine haul in the millions, Ekathimerini, 2 July 2019, https://www.ekathimerini.com/news/242107/piraeus-counterfeit-captagon-amphetamine-haul-in-the-millions/. ↩

-

Dajkó Ferenc Dániel, A tapasztalt nyomozók is megdöbbentek a csempészcigi mennyiségén - videó a cikkben, Növekedés, 10 November 2021, https://novekedes.hu/nav-infotar/a-tapasztalt-nyomozok-is-megdobbentek-a-csempeszcigi-mennyisegen-video-a-cikkben. ↩

-

For more information on the Global Organized Crime Index, see https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/ocindex-2021/. ↩

-

Online interview with the manager of port security for a US port, October 2021. ↩