Digital dangers: warning signs from North Macedonia.

In late January 2021, police in North Macedonia broke up a group of more than 7 000 people who were using the Telegram online messaging app to share explicit pictures and videos of women and girls.1 In the forum known as the ‘public room’ (created in 2019), members shared pornographic content and child abuse material, including nude pictures of teenage girls from the local community. The material had been previously hacked, stolen, photoshopped or otherwise obtained illegally along with victims’ personal data like names, surnames and telephone numbers.

Although the group was first discovered in January 2020 and four people were arrested, by January 2021 it had re-emerged, leading to a public outcry over police inactivity. Similar cases were also reported in Serbia in March 2021, when several offenders were arrested for sharing child abuse material and were given sentences of up to 10 years in prison.2 These cases show the growing dangers of tech-facilitated crime, including cyberbullying, sexual exploitation and sextortion in the Western Balkans, and the challenges faced by law enforcement in dealing with it.

In North Macedonia, which has a population of around 2.1 million people, there are 2.24 million registered mobile phones – more phones than people.3 According to information from January 2020, 81% of the population of North Macedonia uses the internet and 53% of the population are active social media users. And the trend is increasing, partly because of COVID-19, particularly as children are spending more time online because of remote schooling and lockdowns. The speed and magnitude of this transition has caught the authorities, parents and children off guard.4

As in other parts of the world, young people are particularly active online. Almost 75% of all young people in North Macedonia between the ages of 15 and 19 have a profile on social networks.5 The majority of those who use social media access their accounts from smartphones.6 Children and youth are also spending more time gaming online and they are increasingly meeting new friends through such forums as well as via social media.7

While greater digitalization has many benefits, it also has dangers. The ‘public room’ case shows the risks of data being stolen or exploited and the harassment that can result.8 In addition, gaming platforms – and social media more generally – are being abused to groom children for sexual harassment and exploitation. Young people are also vulnerable to harmful and violent content, cyberbullying and radicalization.

A major challenge is that the privacy of children and youths can be easily compromised. To stay recognizable among their online competitors, young people create usernames that are derivatives of their real names or that might reveal other personally identifiable information, such as their location or age. This makes it easier for online predators and cybercriminals to manipulate data, chats or photos for identify theft, grooming or sextortion.9

Young people are also vulnerable to stalking, cyberbullying or even commercial sexual exploitation. Sometimes, this is the result of information provided wittingly (albeit naively); in other cases, hackers can access webcams or microphones and use them to commit illegal activities and violate the privacy of children and youth. Only 11% of interviewed students in North Macedonia are aware of webcam or microphone hacking and the consequences this may cause.10

What is tech-facilitated CSEC and how does it work?

Tech-facilitated commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) usually refers to the use of the internet as a means to exploit children sexually, including cases in which offline physical child abuse and/or exploitation is combined with an online component.11 Although tech-facilitated sexual exploitation is constantly evolving and shaped by new developments in technology, it often starts with grooming (establishing a relationship with a minor victim), then ‘sexting’ (creating and/or sharing sexually suggestive images of the victim), sextortion (blackmailing the child victim with their own images to extort sexual favours or money) or live sexual abuse (coercing a child into sexual activities) and child sexual abuse material.

Figure 3 Stages and elements of online CSEC.

ECPAT International, Online child sexual exploitation: A common understanding, May 2017, https://www.ecpat.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/SECO-Booklet_ebook-1.pdf.

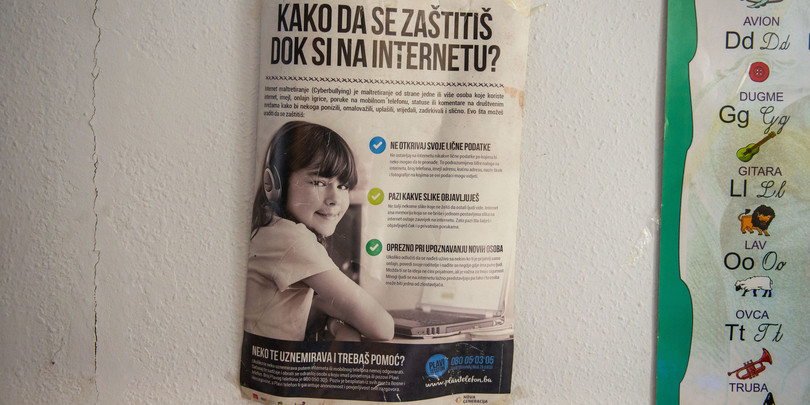

Information sheet on how to safely use the internet displayed at a youth center in Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Photo: © Bahrudin Bandić

A youth centre in Belgrade, Serbia, provides information and supervision for a ‘safe time online’.

Photo: © Vladimir Zivojinović

For example, older gamers may use video games to lure and groom younger victims. Hiding behind false identities, predators become accustomed to the platforms, phrases, habits and interests of the potential victims. They lure them into separate chats and skilfully earn their trust.

Despite important cases such as the Telegram incident, there is little comprehensive research on tech-facilitated CSEC in the Western Balkans. Countries do not provide disaggregated data on the topic. An upcoming GI-TOC report tries to fill this gap by looking at children’s vulnerabilities to tech-facilitated CSEC and the responses of the child protection systems across the region.

Another threat is the harvesting of data from the profiles of young people. Marketing and the collection of user data in exchange for behaviourally targeted or contextual advertising are embedded parts of modern gaming profit schemes.12 To conduct behavioural targeting, multiple bits of data are acquired and combined to develop sophisticated profiles of user segments and to build a profile of the characteristics and demographics of individual users.13 In the case of online gaming, some companies may collect data not only on user behavioural patterns but on their interactions with other users, online behaviour before and after playing an online game and behaviour across multiple devices and services linked to their gaming device. The problem with who owns this data, how it is protected, shared and sold (both to private companies and criminal groups) is an emerging issue that requires greater attention and regulation.14

Unauthorized practices by online vendors raise concerns about the privacy of young people. The issue is gaining increasing attention from international organizations like the United Nations,15 the Council of Europe16 and the EU.17 For example, the EU has adopted a General Data Protection Regulation, which contains rules intended to protect children from unlawful data collection, with severe sanctions on companies that do not comply.18

In short, the dangers to children online are multiple and diverse. And they are compounded by insufficient awareness by parents and children, a dearth of data, lack of knowledge and capacity by police investigating online crime, inadequate legislation and limited cooperation between law enforcement and IT providers across borders.

The first step is for governments to acknowledge the growing dangers of exploitation online. Adequate legislation is also necessary, but it is not sufficient. Greater attention needs to be given to raising awareness among parents and children about the potential risks and to improve online vigilance and literacy. In North Macedonia, several initiatives have been started to address online predation, cyberbullying and cybercrime, as well as disinformation and online radicalization. The Ministry of Interior has set up the Red Button reporting scheme on its website to report crimes related to child sexual abuse and hate speech online.19 But greater awareness is needed, for example through education in schools, public campaigns and more engagement by civil society to reduce the vulnerability of young people to online harm. And law enforcement need the skills, expertise, equipment and licence to protect citizens, young and old, in the digital domain.

The role of the private sector is essential. The tech sector should help to develop national cyber strategies and be involved in their implementation. Currently, the information and communications technology (ICT) industry in North Macedonia does not address the issue of tech-facilitated CSEC, nor is it involved in content removal or reporting mechanisms.20 Service providers do not proactively monitor online content and do not have any obligation to remove content. Internet Service Providers act only upon the request of the public prosecutors and deliver data to the Ministry of the Interior’s Sector for Cybercrime and Forensic Analysis for further processing.

In short, while we spend more time online, so do criminals. Reducing the risks to children requires a whole-of-society approach, including more vigilant and aware parents and young people, a solid legal framework, a forward-looking and engaged ICT sector, more effective law enforcement responses and the support of civil society.

A comprehensive report on the commercial sexual exploitation of children in the Western Balkans will be issued by the GI-TOC in May.

Notes

-

Bojan Stojkovski, North Macedonia Threatens to Block Telegram Over Pornographic Picture Sharers, BalkanInsight, 29 January 2021, https://balkaninsight.com/2021/01/29/north-macedonia-threatens-to-block-telegram-over-pornographic-picture-sharers/. ↩

-

Slučaj ‘Telegram‘: Za deljenje pornografskog materijala i do 10 godina zatvora, N1, 10 March 2021 https://rs.n1info.com/vesti/slucaj-telegram-za-deljenje-pornografskog-materijala-i-do-10-godina-zatvora/. ↩

-

Simon Kemp, Digital 2020: North Macedonia, DataReportal, 18 February 2020, https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-north-macedonia. ↩

-

Daniela Trajkovska Zdravkovska, Родители, не бидете оф додека децата ви се он!, Nova Makedonija, 15 August 2018, shorturl.at/fuBH5. ↩

-

Спасовски, Манчевски и Адеми дел од настанот ‘Патувачка училница’: Само со хоризонтален пристап ќе се зајакнат капацитетите и свесноста за сајбер безбедност од најмала возраст, Ministry of International Affairs of North Macedonia, 16 October 2019, https://mvr.gov.mk/vest/10216?fbclid=IwAR3OghzMlJB9-s90iHlS2bvWqqUlRTf1m-wNV7jffD_Ni7m6WxPvYh3-z8Y. ↩

-

Simon Kemp, Digital 2020: North Macedonia, DataReportal, 18 February 2020, https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-north-macedonia. ↩

-

Amanda Lenhart et al., Teens, Technology and Friendships, Pew Research Center, 6 August 2015, 2, http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/08/06/teens-technology-and-friendships. ↩

-

Metodi Hadji-Janev, Mitko Bogdanoski and Dimitar Bogatinov, Towards safe and secure youth online: Embracing the concept of media and information literacy, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and C3I, January 2021, https://www.kas.de/documents/281657/281706/Belegexemplar+2020+Publ+Toward+safe+and+secure+youth+online+ENG.pdf/b4e1f2b6-f8a9-18a4-6be7-bcc1e36785fd?version=1.0&t=1611828138369. ↩

-

See for example: Nellie Bowles and Michael Keller, Sextortion: Trauma of online abuse through gaming can be overwhelming for its victims, The Irish Times, 22 December 2019, https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/health-family/parenting/sextortion-trauma-of-online-abuse-through-gaming-can-be-overwhelming-for-its-victims-1.4110859. ↩

-

Interview with cybercrime expert Milan Stefanoski, February 2021. ↩

-

This can include: the production, dissemination and possession of child sexual abuse materials; online grooming of children for sexual purposes; sexual extortion of children; revenge pornography; commercial sexual exploitation of children; exploitation of children through online prostitution; and live-streaming of sexual abuse. See UNICEF, What Works to Prevent Online and Offline Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse? Review of national education strategies in East Asia and the Pacific, 2020, vii, https://www.unicef.org/eap/media/4706/file/What%20works.pdf. ↩

-

Simone van der Hof et al., The child’s right to protection against economic exploitation in the digital world, The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 28, 4, 833–859. ↩

-

Gary DeAsi, 10 Powerful Behavioral Segmentation Methods to Understand Your Customers, Pointillist, 22 December 2020, https://www.pointillist.com/blog/behavioral-segmentation. ↩

-

UNICEF, Child rights and online gaming: opportunities and challenges for children and the industry, Discussion Paper, August 2019, https://www.unicef-irc.org/files/upload/documents/UNICEF_CRBDigitalWorldSeriesOnline_Gaming.pdf; and UNICEF, Privacy, protection of personal information and reputation, Discussion Paper, March 2017, https://sites.unicef.org/csr/css/UNICEF_CRB_Digital_World_Series_PRIVACY.pdf. ↩

-

UNICEF, Child rights and online gaming: opportunities & challenges for children and the industry, Discussion Paper, August 2019, https://www.unicef-irc.org/files/upload/documents/UNICEF_CRBDigitalWorldSeriesOnline_Gaming.pdf. ↩

-

Council of Europe, Guidelines to respect, protect and fulfil the rights of the child in the digital environment, September 2018, https://rm.coe.int/guidelines-to-respect-protect-and-fulfil-the-rights-of-the-child-in-th/16808d881a. ↩

-

European Commission, Reform of EU Data Protection Rules, 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection/eu-data-protection-rules_en. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

For more information, see: http://www.govornaomraza.mk/. ↩

-

The Chamber of Commerce for Information and Communication Technologies (MASIT) represents the North Macedonian ICT industry and promotes and represents the business interests of ICT companies in order to promote and develop the ICT industry and business environment. For more information, see https://masit.org.mk/en/about-us/. ↩