Guns for gangs in Sweden: the Balkan connection.

In Sweden, the notorious Yugoslav mafia that dominated the organized crime landscape in Stockholm in the 1990s – the so-called Juggemaffian – is long gone, but criminal connections to the former Yugoslavia are alive and well.

In the past few years, organized crime has increased dramatically in Sweden, with some of the weapons and drugs coming in from the Western Balkans. ‘What we’ve seen in the past few years are organized crime groups mostly based in Serbia that set up proxies in Sweden to receive shipments of drugs and weapons,’ said Detective Superintendent Gunnar Appelgren,1 one of Sweden’s most experienced organized crime investigators.2

These groups are not of the same profile as the Juggemaffian. This organized crime group, which operated among the diaspora of refugees who had fled the former Yugoslavia during the Balkan Wars (‘jugge’ is slang for Yugoslav), made most of their money from protection rackets and extortion. According to a former hitman, Janne Raninen,3 who murdered Swedish-Serbian mobster Dragan Joksović in 1998 near Stockholm,4 the Juggemaffian’s clout was based more on a brash image of ‘shiny suits and bulging muscles’ rather than on violence. In retrospect, ‘they looked like amateurs compared to the gangs we have now’.5

However, criminal groups from the Western Balkans are not among the most dominant in Sweden today. The main actors are long-established motorcycle gangs and family- based organizations sometimes referred to as criminal clans.6 There are also more fluid groups that are mostly in charge of the sale of narcotics in poorer neighbourhoods.7

Some groups are named after the neighbourhoods where they operate, while others take on more cinematic monikers such as Shottaz, a group of young men who belong mainly to the Swedish-Somali community in northwestern Stockholm, or the Network, a notorious group of loan sharks that has exploited its own community of Orthodox-Christian immigrants from the Middle East for decades.8 Many of these groups share the same arms dealers who provide weapons from the Western Balkans, including Kalashnikov assault rifles, Serb-manufactured Zastava pistols and hand grenades.

A Swedish policeman investigates a crime scene.

In 2015, the National Police presented a graphic of shootings with confirmed or suspected ties to ‘criminal environments’ showing that murders had nearly doubled between 2014 and 2015.9 After a further surge, the number of murder victims across the country has surpassed around 40 each year,10 with most related to organized crime.

In 2018, the government reformed the law, lengthening prison sentences for aggravated weapons crimes.11 The updated legislation allowed police to intensify surveillance of key actors and to conduct more raids, which increased the number of seized weapons. However, gangs have delegated the task of transporting and storing guns, rifles and hand grenades to teenagers who act as errand boys. In a recent report by public service radio, police chiefs across the country confirmed the trend of gangs using younger members who, if caught, face shorter prison sentences due to their age.12

The decreasing age of errand boys is seen as a legislative failure, which critics had warned the government about before the reform. Furthermore, the increase in successful weapon raids has not led to a reduction in violent crime: police statistics for 2020 show a marginal increase in shooting deaths over the previous year. In addition, 117 people suffered non-fatal gunshot wounds in 2020, compared to 120 in 2019.13

Modified starter pistols have become more common in criminal circles in Sweden in recent years, but most weapons used in shootings still hail from the former Yugoslavia, according to police analysts.14 At Karolinska Hospital north of Stockholm, an intensive-care doctor who did not want to be named pointed out that surgeons have grown accustomed to operating on shooting victims. There is a greater chance of survival, the doctor pointed out, if the shots have been fired from a lower-calibre weapon, such as a Zastava pistol. These weapons remain popular: a 2020 police report found that one third of illegal handguns in Stockholm county were Zastavas.15

Stopping illegal arms smuggling has been a priority for almost a decade. In 2012, the government gave Swedish customs the task of intercepting weapons. Around the same time, all key public agencies, including customs and the police’s financial crime unit, created a council to work together holistically and tackle organized crime from all sides.

International cooperation has also evolved. In 2018, the Swedish police joined forces with their Serbian counterparts to combat the influx of weapons. Gothenburg police chief Erik Nord told Swedish television that, during a meeting in Belgrade, the Serbian police officers ‘raised their eyebrows’ in incredulity when he described the number and nature of gang murders in Sweden.16 In 2019, Swedish Foreign Minister Ann Linde and her colleague, Interior Minister Mikael Damberg, visited Albania and Bosnia and Herzegovina to learn about best practices in combatting transnational crime and discuss ways forward. ‘We have to do more to cut off the flow of narcotics and illegal weapons to our country,’ Damberg said in a press release.17 ‘We know that our international cooperative efforts have led to the police being able to seize more [narcotics and illegal weapons] from serious criminals in Sweden. By going further with this kind of cooperation, society can attack organized crime in a better and more effective way.’

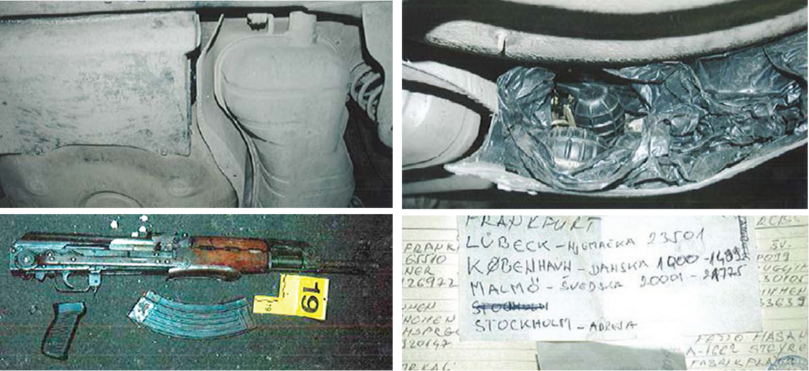

Findings from a Swedish police intelligence report on the Operation Rekyl investigation.

In 2014, Operation Rekyl (Operation Recoil) became one of the first large-scale international investigations. It was initiated after the discovery of five automatic weapons and 59 hand grenades in a car travelling from Slovenia to Sweden.18 Appelgren led a team of Swedish investigators in cooperation with Slovenian, Bosnian and Serbian colleagues to bring down a weapon-smuggling network.

After six months of surveillance, charges were brought against a Bosnian couple and several of their associates, including Swedish nationals. The ringleader was found guilty by a Swedish court and sentenced to five years in prison for attempted aggravated smuggling. However, the charges of aggravated weapons crime did not stick, despite his associates having been caught with Kalashnikovs and hand grenades – some of them rusty, testifying to the long shadow of the Balkan wars.

The weapons arsenal left behind in the Balkans appears to be unlimited, despite attempts to collect surplus weapons. The United Nations, for example, has assisted the authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina with several amnesty schemes. ‘People who handed in weapons were given lottery tickets with very good prizes, such as fridges,’ said Christine McNab, the UN Resident Coordinator in Sarajevo between 2002 and 2006.19 ‘But we noted that many of the weapons were quite old and we always had a sneaky feeling that these weapons were “grandad’s second-world-war rifle”, not the Kalashnikovs that people had hidden under barn floors.’

As long as demand remains high in countries such as Sweden, that hidden stock of weapons risks ending up in the hands of smugglers. According to Appelgren, the only way forward is to intensify cross-border cooperation even further, as today’s structures are ‘insidious’.20

After Operation Rekyl – which one newspaper called a law-enforcement fiasco – the Swedish justice minister at the time, Morgan Johansson, promised and later delivered on legal reform meant to not only increase the likelihood that such criminals would be brought to justice, but that they would also be found guilty of weapon crimes. After the Swedish investigation’s patchy success, Bosnian prosecutors stepped in, successfully charging several people connected to the scheme, thanks in part to evidence obtained at several weapon-storage facilities located by the Bosnian police in Republika Srpska, in northern Bosnia.

Prosecutor Goran Glamocanin pointed out that while most of the weapons in this case had been smuggled to the harbour city of Gothenburg on Sweden’s west coast, the investigation had spanned most of the country. ‘Because of the good possibilities of making money quickly, criminal groups have collected illegal weapons and put in place measures to transport them to Sweden,’ Glamocanin told the press.21 ‘The number of cases we are trying does speak to Sweden still being an important market for smugglers.’

Weapons originating in the Balkans continue to have an impact far beyond the region, meaning that states have an ongoing shared interest in reducing their vulnerability to this threat.

Notes

-

Interview with Gunnar Appelgren, December 2020. ↩

-

Kina Pohjanen, Gängspecialist värvad till Uppsala, SVT, 15 October 2020, https://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/uppsala/gangspecialist-varvad-till-uppsala. ↩

-

Interview with Janne Raninen, November 2020. ↩

-

Janne Raninen and Ivar Andersen, De kallar mig Solvallamördaren. Lind & Co, February 2018, https://www.lindco.se/bocker/de-kallar-mig-solvallamordaren/. ↩

-

Interview with Janne Raninen, November 2020. ↩

-

Johanna Bäckström Lerneby, Familjen, Mondial, May 2020, https://mondial.se/bok/familjen/. ↩

-

Isak Krona, Underrättelsechefen: Jobbar mot tre olika sorters nätverk, Sveriges Radio, 7 September 2020, https://sverigesradio.se/artikel/7548857. ↩

-

Ann Törnkvist, Follow F*ing Orders, Pitch, 17 August 2020, https://www.pitchpublishing.co.uk/shop/follow-fing-orders. ↩

-

Dramatisk ökning av dödsskjutningar, SVT, 16 November 2016 https://www.svt.se/nyheter/inrikes/dramatisk-okning-av-dodsskjutningar. ↩

-

Official police statistics for 2020, https://polisen.se/om-polisen/polisens-arbete/sprangningar-och-skjutningar/. ↩

-

Regeringen föreslår ytterligare skärpta straff för vapenbrott, Justice Department press release, 5 June 2020, https://www.regeringen.se/pressmeddelanden/2020/06/regeringen-foreslar-ytterligare-skarpta-straff-for-vapenbrott. ↩

-

Slopad straffrabatt för unga myndiga vid allvarlig brottslighet, Justice department press release, 10 July 2020, https://www.regeringen.se/pressmeddelanden/2020/07/slopad-straffrabatt-for-unga-myndiga-vid-allvarlig-brottslighet. ↩

-

Swedish police statistics, 15 December 2020, https://polisen.se/om-polisen/polisens-arbete/sprangningar-och-skjutningar/. ↩

-

Interview with a local investigative journalist, on 3 January 2021, referring to data drawn from interviews and off-the-record conversations with Stockholm police. ↩

-

Illegal vapenanvändning i polisregion Stockholm – Strategisk 50 rapport, Police Authority, Stockholm police region, May 2020, https://polisen.se/aktuellt/nyheter/2020/juni/illegala-vapen-ateranvands-ofta. ↩

-

Jakob Eidenskog, Så ska vapensmuggling från Balkan stoppas, SVT, 6 December 2018, https:/www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/51vast/sa-ska-vapensmuggling-fran-balken-stoppas. ↩

-

Ann Linde och Mikael Damberg till Bosnien och Hercegovina samt Albanien för möten om organiserad brottslighet, government press release, 5 October 2020, https://www.regeringen.se/pressmeddelanden/2020/10/ann-linde-och-mikael-damberg-till-bosnien-och-hercegovina-samt-albanien-for-moten-om-organiserad-brottslighet. ↩

-

Södertörn district court case number B 4736-16. ↩

-

Interview with Christine McNab, December 2020. ↩

-

Interview with Gunnar Appelgren, December 2020. ↩

-

Bosnisk åklagare: ‘Sverige är Balkans största vapenmarknad’, Aftonbladet, 22 January 2018, https://www.aftonbladet.se/nyheter/a/WLq39a/bosnisk-aklagare-sverige-ar-balkans-storsta-vapenmarknad. ↩