Online trade of pangolin products in China is driving pangolin trafficking in eastern and southern Africa.

The pangolin – often described by conservation organizations as ‘the world’s most trafficked mammal’ – has home ranges across eastern and southern Africa. Out of eight recognized species of pangolin, three species can be found in East Africa and one in southern Africa. Pangolin are under immense pressure from poaching and trafficking to meet the demand for meat and scales as well as body parts used in traditional medicine. While some pangolins in Africa are poached for consumption on the continent, the bulk are trafficked to China, where there is a large (legal) domestic market for pangolin-derived products.1

The GI-TOC’s new research, in collaboration with the University of Oxford and the Zoological Society of London, focuses on the online market for pangolin and pangolin-derived products in China, an under-researched area of the pangolin trade. Our research found that the marketing of pangolin-derived products online in China largely does not follow applicable laws and regulations. This has implications for pangolin populations in eastern and southern Africa and the ongoing trafficking of African pangolin to meet the demand for pangolin in Asia.

Snapshot of the pangolin trade in China

The commercial international trade in pangolins and pangolin parts has been illegal under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) since 2017. Most countries also ban the domestic trade of pangolins, with the notable exceptions of China, Gabon and Sierra Leone. Despite this, multi-tonne seizures of illegal shipments of pangolins, pangolin scales and other parts from both Africa and Asia are made regularly. Although national and international legislative protection measures have steadily improved, the enforcement of these laws remains inadequate, ineffective and under-resourced, enabling the continuation of the trade.

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime estimates that, in 2018, customs agencies seized the equivalent in scales, meat and bones of about 141 000 live pangolins. It is estimated that, in central Africa alone, between 400 000 and 2.7 million pangolins are poached every year.2

China is home to three species of pangolin, all of them protected species. If caught, pangolin traffickers in China face high penalties or jail sentences. However, the trade in pangolins and pangolin derivatives is allowed to operate under certain legal conditions. Manufacturers seeking to buy and use pangolin parts need to first obtain several authorizations from different government agencies.

According to China’s Wildlife Protection Law, in order to use pangolin scales in the manufacturing of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) drugs and other items, companies in China can obtain a permit from the State Forestry and Grassland Administration. Drugs containing pangolin scales (as well as a selection of other endangered species) cannot be legally sold without displaying the China National Wildlife Mark (CNWM) logo.

An advertisement for Kangshuan Jiaonang, a medication that contains pangolin scales. The CNWM label is not displayed on the product packaging that is advertised on the website.

Photo: 360kad.com

The CNWM logo informs customers that the drug contains ingredients derived from a protected species. It also lets them know the species concerned and tells them that the ingredient was legally sourced, in addition to indicating how it was sourced (whether from the wild or from farms).

Our research found that the CNWM requirement remains largely unobserved in online advertisements, with some websites deliberately hiding the presence of pangolin in their products.3 Pangolins and TCM drugs listing pangolin products are also widely advertised online and available for international shipping on some sites, without clear indications about the origin of the scales. This practice may be fuelling demand for illegally trafficked pangolin scales from Africa.

Pangolin trade in eastern and southern Africa

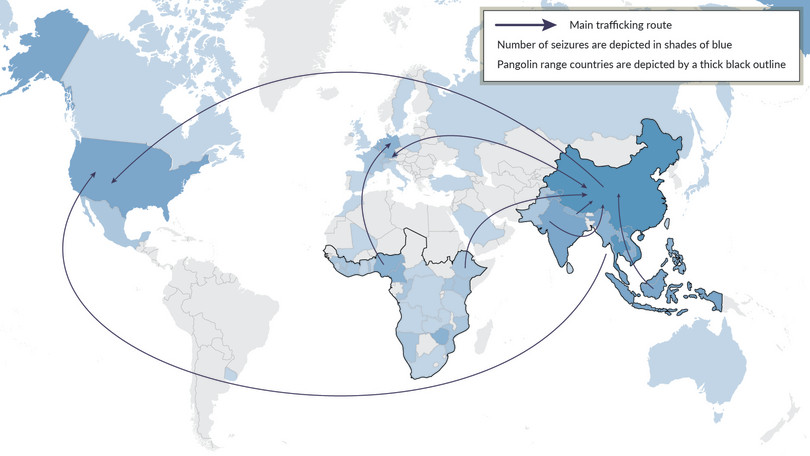

Figure 1 Main trafficking routes linking range states and consumption markets for pangolins.

Note: The figure does not present the total relative volume of scales.

Some of the largest confiscations of African pangolins and pangolin scales were recorded in Asia between 2017 and 2019, with more than 609 confiscations of 244 600 kilograms of pangolin scales and 10 971 individual animals, according to data from wildlife-trade monitoring group TRAFFIC.4 These figures show the scale of demand for pangolin in Asia and illustrate the role that Africa plays in feeding this demand. Pangolin seizures reduced significantly between 2020 and 2021, with 233 seizures in Asia of 13 389 kilograms of scales and 247 individual animals recorded.5 These low numbers have been attributed to global travel restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic and do not necessarily reflect a reduction in demand for pangolin.6

In southern Africa, data on pangolin seizures from 2018–2022 from the Wildlife Seizure Dashboard, aggregated by the Centre for Advanced Defense Studies, shows that Namibia has the highest number of pangolin seizures, followed by Malawi, South Africa and Zimbabwe.7 High seizures in Namibia have been attributed to increasing drought conditions in the country, which have forced these nocturnal animals to forage for food during the day.8 However, as pangolin populations in East Africa dwindle, environmental experts anticipate that more seizures will take place in southern Africa.9

Zambia has the highest record of pangolin seizures at its airports.10 The pangolins and pangolin parts seized at airports in southern Africa are mostly been destined for Asia.11 Most of these items have been discovered in luggage and air freight, as traffickers usually transport medium to large shipments.12 South Africa leads the number of recorded instances of pangolin seizures destined for China, mostly via Hong Kong, perhaps in part thanks to its major airports, which act as international and regional hubs, providing a gateway for international trafficking routes.13

Figure 2 Wildlife seizures in southern Africa en route to Asia.

Oxpeckers, How pangolins are smuggled from Southern Africa, 3 June 2022, https://oxpeckers.org/2022/06/how-pangolins-are-smuggled/

In East Africa, pangolins are also heavily targeted for poaching and trafficking. Uganda, for example, is home to three of the four pangolin species found in Africa: the ground pangolin, giant pangolin and white-bellied pangolin. In March 2022, state prosecutors from 11 countries in East Africa formally pledged to increase cross-border cooperation to combat wildlife trafficking and money laundering in recognition of the problem of pangolin poaching.14 This followed queries by environmental activists over the low level of prosecutions and the lenient penalties issued in Uganda.15 It remains to be seen whether these pledges will yield any results for Africa’s endangered pangolin species.

New research on the digital market for pangolin and pangolin-derived products

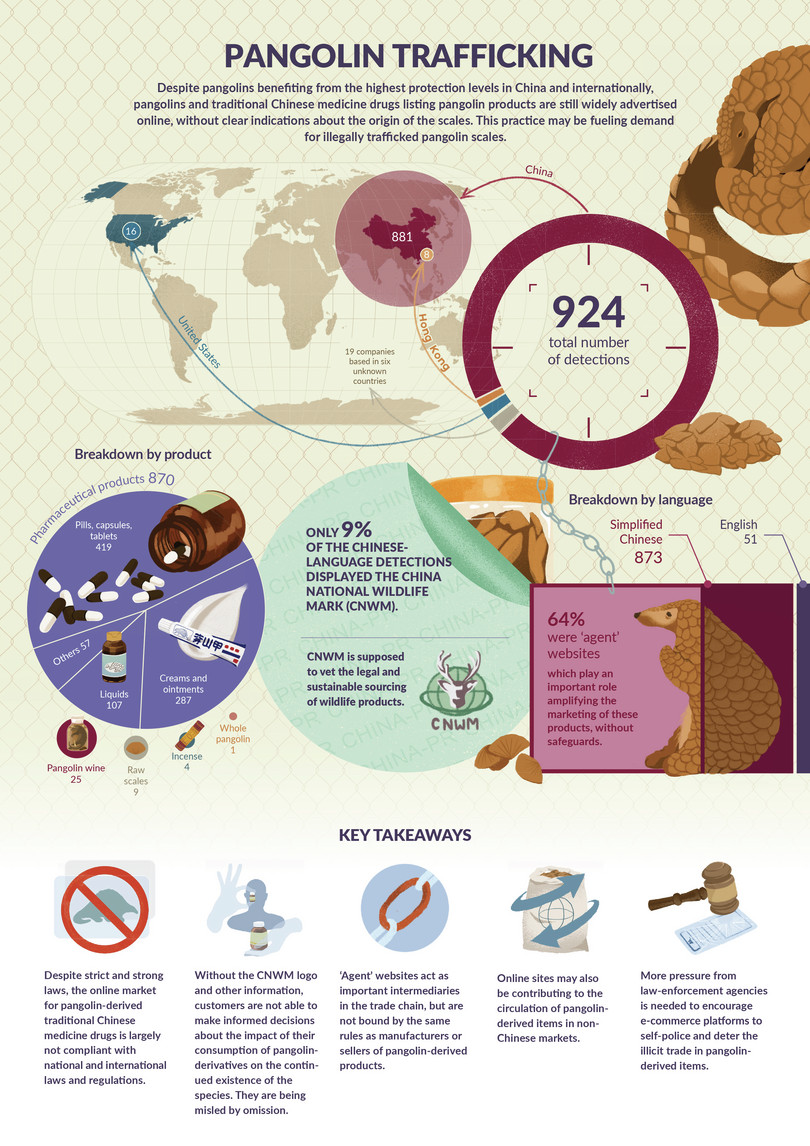

Our research on the digital market for pangolin and pangolin-derived products uncovered some attempts to bypass legal requirements for the marketing and sale of such items. The research sheds light on the use of pangolin parts and scales in the manufacturing of a number of items, especially TCM remedies, and provides evidence that the internet plays a major role in the trade of pangolin-derived products, thus fuelling the demand for pangolin.

The research made use of a machine-learning-based tool called Cascade, programmed to monitor online platforms advertising pangolin-derived items in English and Chinese.16 The technology detected nearly a thousand instances of retail and classified websites offering pangolin-derived TCM drugs, wine and incense over a six-month period (April 2021 to October 2021), in addition to advertisements for raw and processed scales and body parts. Most of the advertisements were posted on Chinese-language websites, many of which offer to ship their products internationally. As a result, these products may well be imported into European and North American countries and sold to consumers based in regions where the sale of pangolin products is prohibited.

The research found major trade-compliance gaps in Chinese laws, which allow a vibrant trade of pangolin-derived products to take place online on classified platforms and facilitated by third-party ‘agents’.

Pangolin products are still being widely advertised online, without any clear indications about the origin of the scales – omitting, for example, the CNWM logo and other legally required information. The absence of the CNWM logo results in customers unable to make informed decisions about the impact of their consumption of pangolin derivatives on the environment and global biodiversity. This is because the CNWM label is the only means by which customers are able to directly verify whether TCM products have sourced wildlife ingredients – such as pangolin scale – through legal and sustainable channels.

A rescued pangolin in Johannesburg. Pangolins and pangolin parts seized at airports in southern Africa are mostly being destined for Asia.

Photo: Luca Sola/AFP via Getty Images.

The digital market may also be contributing to the circulation of pangolin-derived items in non-Chinese markets. Thirty-one websites in our sample were found to be advertising pangolin-derived products to consumers outside of China. These sites are therefore advertising these products in areas where there are strong legal prohibitions on the trade of pangolin-derived products, and all sales should expose market actors to legal actions because of the international trade of pangolin being prohibited. Twenty-four out of 55 detected advertisements offering pangolin-derived products to consumers outside of China found using Cascade obscured the presence of pangolin in the list of ingredients.

There are major trade-compliance gaps in Chinese laws, which allow a vibrant trade of pangolin-derived products to take place online.

Overall, the online market for pangolin-derived products may be driving demand for illegally trafficked pangolin scales. This is because the online market does not follow the full scope of laws regulating the market in China and internationally. More pressure from law enforcement agencies is needed to encourage e-commerce platforms to self-police and deter the illicit trade in pangolin and pangolin-derived products.

A regulation problem with global reach

Pangolins are threatened with extinction and the online trade of pangolin-based products only increases this threat of extinction. Data on pangolin seizures in southern Africa shows that pangolin populations are increasingly under threat, as populations in East Africa and other parts of the continent dwindle. This is likely to lead to an increase in trafficking from southern Africa to meet the demand for pangolins and pangolin parts, particularly in Asian countries. While China has a legal framework for regulating and restricting the illicit trade of pangolin-derived items, and endangered species in general, pangolin products continue to be sold openly online.

Notes

-

Calistus Bosaletswe, How pangolins are smuggled from southern Africa, Oxpeckers, 3 June 2022, https://oxpeckers.org/2022/06/how-pangolins-are-smuggled; and Jimmiel Mandima, Pangolins pushed to extinction as demand for scales grows, African Wildlife Foundation, https://www.awf.org/blog/pangolins-pushed-extinction-demand-scales-grows. ↩

-

UN Office on Drugs and Crime, World wildlife crime report: Trafficking in protected species, 9 July 2020, https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/wildlife/2020/World_Wildlife_Report_2020_9July.pdf. ↩

-

Théo Clément, Simone Haysom and Jack Pay, Online markets for pangolin-derived products: Dynamics of e-commerce platforms, GI-TOC, July 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/online-markets-for-pangolin. ↩

-

TRAFFIC, Asia’s unceasing pangolin demand, 19 February 2022, https://www.traffic.org/news/asias-unceasing-pangolin-demand. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Calistus Bosaletswe, How pangolins are smuggled from southern Africa, Oxpeckers, 3 June 2022, https://oxpeckers.org/2022/06/how-pangolins-are-smuggled. ↩

-

Helge Denker, The plight of the Namibian pangolin, The Namibian, 6 February 2020, https://www.namibian.com.na/197726/archive-read/The-plight-of-the-Namibian-pangolin. ↩

-

Calistus Bosaletswe, New data provides a glimpse into SA’s illegal pangolin trade, Oxpeckers, 23 June 2022, https://oxpeckers.org/2022/06/sas-illegal-pangolin-trade. ↩

-

Calistus Bosaletswe, How pangolins are smuggled from southern Africa, Oxpeckers, 3 June 2022, https://oxpeckers.org/2022/06/how-pangolins-are-smuggled. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Mary Utermohlen and Patrick Baine, In plane sight: Wildlife trafficking in the air transport sector, 6 August 2018, https://c4ads.org/reports/in-plane-sight. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Benjamin Jube, Uganda fights to stop pangolin poaching, Mail & Guardian, 6 June 2022, https://mg.co.za/article/2022-06-06-uganda-fights-to-stop-pangolin-poaching-2. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Cascade generates and expands search queries, using keywords, and searches the web, filtering out irrelevant content. It then produces a set of results deemed most likely to contain the target product or animal for sale. Cascade can perform broad text- and image-based searches in a variety of languages, which make it the perfect tool for detecting online attempts at selling previously identified items containing ingredients derived from endangered species or other specific components. ↩