Kenya grapples with theft of state ammunition.

In 2017, the Small Arms Survey estimated there to be 40 million firearms in civilian possession across Africa. Of these, around 16 million were estimated to be held illegally, 18 million of unclear status and just 5.8 million legally registered.1 Illicit firearms and ammunition are being used by armed groups and organized criminal networks in several African countries to fuel violence and conflict.

Kenya is illustrative of this phenomenon. Research from organizations such as the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the Institute for Security Studies has ranked Kenya among the highest of countries in Africa for illicit firearm possession and seizures of illegal weapons.2

A key factor that enables the use of these illicit firearms is the availability of ammunition, including ammunition from state sources.3 Historically, the Kenyan government itself supplied ammunition to frontier ethnic groups (among them the Turkana, Pokot and Borana) to counter cross-border incursions. Now, authorities are grappling with cases in which state ammunition is being diverted to illegal hands by the same people charged with safeguarding them.4

Illicit sales of ammunition from the General Service Unit

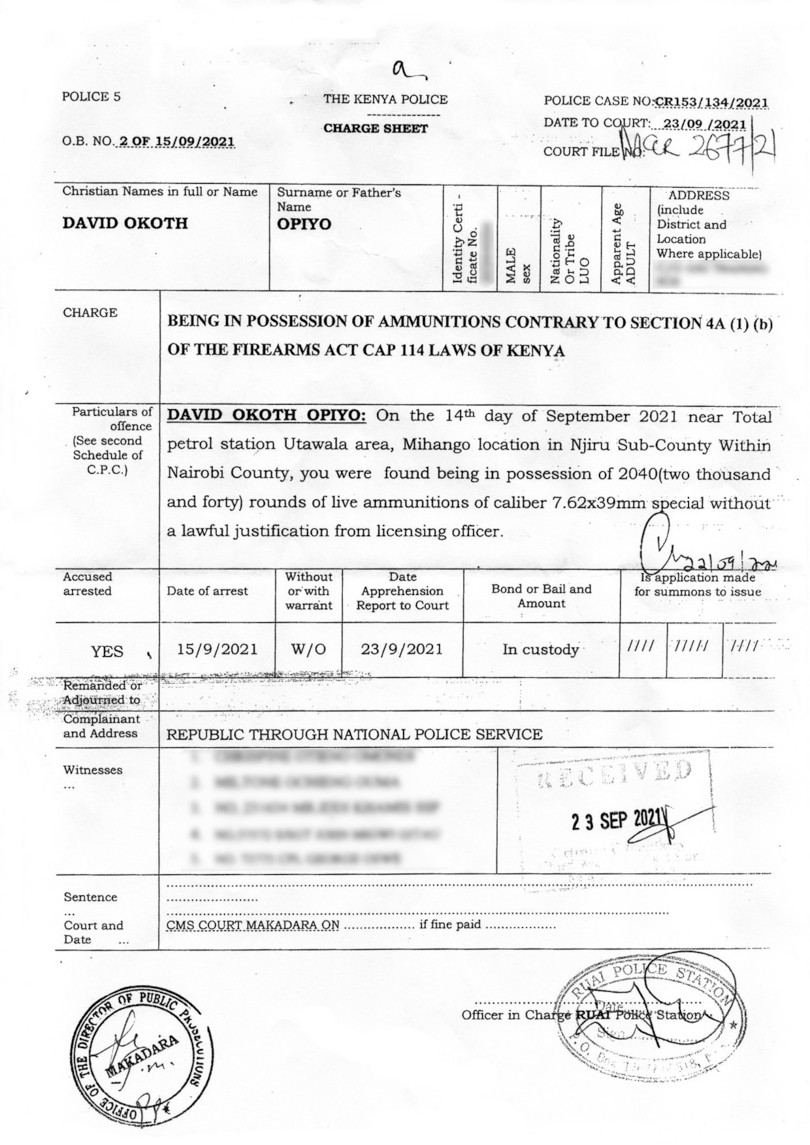

According to a security expert, a high-profile trial, due to begin soon in Nairobi, may shed light on the extent to which state ammunition ends up in wrong hands. David Okoth Opiyo, an inspector with the General Service Unit (GSU), the paramilitary wing of the Kenya Police Service, stands accused of the illegal possession of 2 040 rounds of AK-47 ammunition. He has pleaded not guilty to the charges against him. Opiyo served as an instructor in charge of the armoury at the GSU Training School in Nairobi’s Embakasi district.5 The AK-47 is the firearm of choice for bandits, terrorists and ethnic militias in Kenya, and the same rifle is used by police and military units.6

Opiyo was arrested in September 2021. Police officers found the cache of ammunition that is at the centre of the trial after they responded to a shooting incident in which a lone gunman had fired 20 times at Opiyo’s car. Police at the scene reported suspicions that this was ‘a case of a deal gone sour’, that Opiyo had been attempting to sell the ammunition discovered in his car.7 Opiyo later surrendered himself to the police and said that he had been a victim of carjacking.8

Image of a charge sheet from the Opiyo case.

Photo: supplied.

The discovery of the cache of ammunition in Opiyo’s car came after a series of unconnected, suspicious incidents linked to the GSU and, specifically, officers in charge of weapons armouries, although it is not yet clear if there are any links between these events. Weeks before Opiyo’s arrest, security officers recovered 2 640 rounds of ammunition, believed to be from the same training school, from a group of herders in Laikipia County.9 Laikipia, located about 340 kilometres north of Embakasi, is the site of ongoing police operations.10

Two days later, an instructor based at the Embakasi Training School was killed in unclear circumstances, just a few kilometres from where the rounds of ammunition were found in Laikipia.11 At almost the same time, Corporal Joseph Maghanga, another GSU instructor, was found dead at a quarry in Nairobi.12 Two months before Opiyo’s arrest, an officer at the GSU headquarters in Ruaraka, about 14 kilometres from the Embakasi Training School, went missing. The officer, Corporal Joseph Otieno, had also been deployed in the armoury section.13

Sources told Kenya’s People Daily newspaper that police are investigating the links between these incidents – which have left three serving or former GSU officers dead and a further three abducted with their whereabouts unknown – and the smuggling of ammunition.14 A former GSU officer told us that this ammunition smuggling syndicate within the GSU is responsible for thousands of bullets stolen from police and military arsenals, but that police and military officers have long avoided taking action as it would mean incriminating some of their own.15

The tip of the iceberg of state-ammunition smuggling in Kenya

The Opiyo case has shone a spotlight on the smuggling of state ammunition and arms in Kenya. Yet sources within the National Police Service (NPS), former officers of the GSU, and security experts believe it is part of a much larger problem. According to a Nairobi-based security analyst, the trafficking of state ammunition has been going on quietly for decades and ‘is huge business, drawing networks of law enforcement officers, arms dealers and political warlords in troubled regions in the country.’16

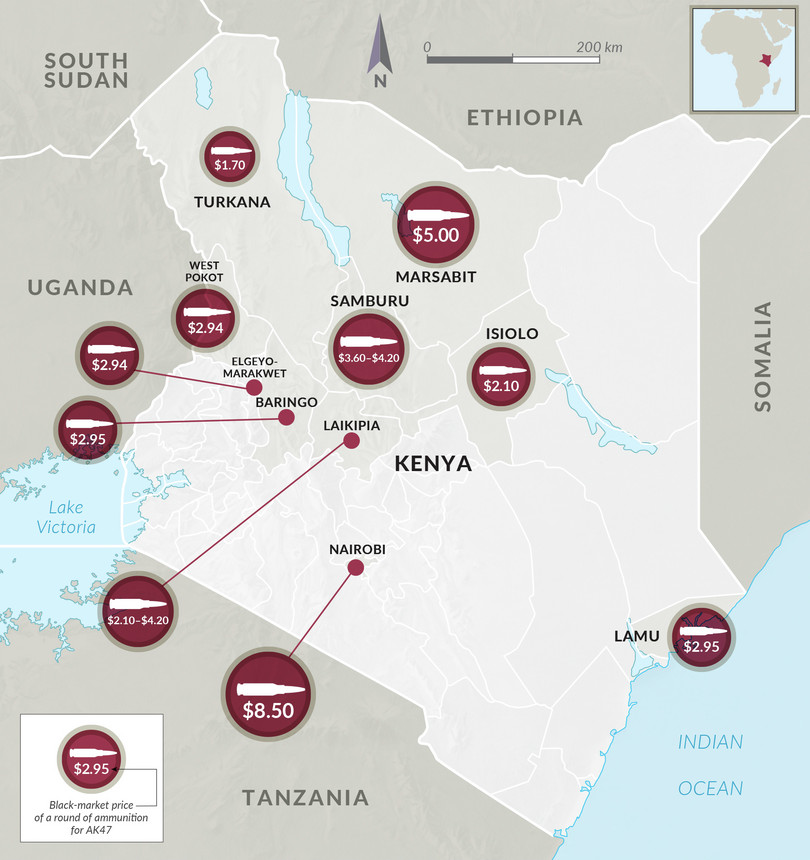

The stolen ammunition fuels conflict and criminality. Some of the stolen stock flows to areas in northern Kenya and the Rift Valley region, which are affected by ethnic violence, cattle theft and banditry. For example, the 2 040 rounds of ammunition seized from Opiyo’s car were reported by police to be destined for Isiolo and Laikipia,17 areas where hundreds of people have been killed and thousands displaced in the past year in clashes linked to this year’s general election. A legislator from Isiolo was the destined recipient of the ‘beans’, the Kenyan slang term for ammunition.18 Nor is this limited to ammunition theft: a March 2022 report from the Kenya National Focal Point on small arms claimed that rogue police officers were leasing out weapons to bandits in the war-strewn counties of Turkana, Baringo, Marsabit, Isiolo, West Pokot and Samburu.19 In urban areas, such as Nairobi, stolen ammunition may be used by criminal groups in armed robberies and carjackings.

Theft of state ammunition in Kenya is fueling conflict and criminality in the country and the wider region.

Photo: Andrew Renneisen/Getty Images.

The trafficking of state ammunition in Kenya ‘is huge business, drawing networks of law enforcement officers, arms dealers and political warlords.’

Our months-long investigation, involving interviews with insiders, former officers and security experts, has exposed a police force lax in accountability and without transparency in record-keeping. The evidence suggests that the GSU is leaking ammunition. However, Unit Commandant Douglas Kanja has dismissed claims that some rogue officers could be involved in the smuggling of ammunition, saying that his unit has foolproof mechanisms to ensure that all supplied ammunition is accounted for.20

Methods of siphoning off state ammunition

Interviews with police officers and security experts described several ways in which state ammunition is stolen. As in many countries, state ammunition in Kenya is not serialized, therefore making it difficult to trace back to a particular source.21

Shooting ranges at officer training schools are a key source of illicit ammunition. Every year, thousands of recruits and officers descend on shooting ranges for training. Officers and instructors in charge of the armoury can falsify records on the amount of ammunition used and use this to siphon off resources. One former instructor told us that an officer can sign off 50 rounds of ammunition for every recruit but hand out just 20.22 At one time during his tenure, the instructor got a directive from a senior government official to supply him with ammunition. ‘I saw this happen a number of times,’ said one former marksman.23

Poor record-keeping within the NPS has led to an absence of accountability at the armouries. A 2018 report from the Independent Policing and Oversight Authority (IPOA)24 noted the ‘manipulation of Arms and Ammunition Movement Register’ to be one of several schemes in which ‘concerted efforts by officers to cover-up crimes’ take place.25 The report recommended that the place review the policies controlling the arms ammunition register.

‘We know this happens, but what can we do? Nothing,’ was the response from a police officer in Nairobi. ‘The range officer has the power to decide your future in the force, so you cannot incriminate them. What happens to the non-expended ammunitions and spent cartridges was none of our business during our time as recruits.’26 During his training, two companies each comprising 180 recruits would go to the shooting range for weeks. Each day, a recruit would be handed five different types of gun and entitled to 10 rounds of ammunition per gun. But the range officer or instructor would only provide half of the ammunition. At the end of the day, as many as 4 500 rounds of ammunition would have been siphoned off.

According to a GSU officer who was, at one time, involved with the administration of the armory at the GSU Training School Embakasi, ‘During my time in the armory at the school I would be summoned by senior officers and ordered to issue ammunition to individuals and record it as being issued for field training. This does not only happen at the training school but also in other stations, but not at large scale compared to the training colleges.’27

Special security operations can also be the source of arms and ammunition leaks. The Kenyan government dispatches special units of the GSU or the military to restore order in areas marred by conflict. Currently, there are special military and paramilitary operations in several regions of Kenya, including Laikipia, Marsabit, Turkana, Elgeyo Marakwet and Wajir, to deal with insecurity occasioned by election violence, terrorism or cattle theft. In Marsabit, for instance, politically instigated ethnic conflict claimed more than 500 lives in the period from April 2021 to April 2022.28

According to a former GSU officer who now runs a Nairobi-based security company, these operations are avenues for the theft of ammunition that eventually gets into the hands of the same criminals that the officers are fighting against.29 ‘We mainly buy these bullets from police. Sometimes they come to this place to conduct security operations to recover stolen animals. They come loaded with bullets, which they sell to us. We also buy from local police posts and patrol bases in North Horr, Maikona and Dukana,’ a herder from Kalacha in North Horr, Marsabit said.30

In addition, not all weapons recovered from bandits or criminals during operations end up in state hands. ‘We don’t keep records and account for all weapons and ammo recovered during security operations, and this allows room for felon officers to steal and sell the same to the same people that they had been recovered from,’ said a senior police officer who has worked in Baringo.31

During civil unrest, such as election violence or violent street protests, police officers are not obliged to account for expended ammunition.32 This provides corrupt police officers with the opportunity to siphon off ammunition from state armouries. According to a police instructor, ‘The tragedy is that police can target innocent civilians just to justify theft of bullets. An officer out to steal bullets can cause a crisis as excuse not to account for bullets.’33

There are also bulks of unused ammunition that had been supplied to different police stations for use by the Kenya Police Reservists (a unit bringing together civilians to assist police with maintaining law and order),34 before the outfit was disbanded. In Marsabit, Elgeyo Marakwet, Baringo and Laikipia counties, this is the ammunition that locals say senior police officers have been selling to them, mainly through brokers.

Figure 1 Black-market prices for AK-37 ammunition in Kenya, 2022.

Note: Price given per bullet.

An infrequently reported issue

In the year to June 2019, Kenya’s IPOA received 3 237 complaints against police misconduct – from both police officers themselves and the public – but none related to the theft of state ammunition.35 The NPS itself has a special unit – the Internal Affairs Unit (IAU) – to receive and investigate misconduct. Similarly, the IAU does not mention the theft of state arms in its latest annual report. The report lists 22 categories of police misconduct, none of them to do with theft or trafficking of firearms or ammunition. Only one case of ‘misuse of firearm’ was recorded among the 1 043 complaints filed with the IAU in 2020.36

A lack of reporting may suggest that police officers are fearful or unwilling to speak out about police misconduct. IPOA’s report also found that one of the key reasons for lack of reporting of complaints by police officers was the ‘fear of victimization’.37 Security experts and former officers described a culture of silence and non-cooperation of police officers with investigations into misconduct.38

Despite this lack of reporting, the IPOA nonetheless recognizes the problem and has recommended that stringent measures are put in place to bring about accountability in the handling of firearms. ‘The Inspector General of the National Police Service should review the policy on arms and ammunition register to ensure that an officer signs upon being issued and on return of the firearm or ammunition. The Inspectorate Department in the Service should be robust and effective to ensure proper records keeping and management of all policing records and registers,’ it recommended in 2018.39

Access to ammunition is key for criminal networks. While arms may have a lifespan of decades, their real value depends upon ammunition supplies. The trafficking of state-owned weapons and ammunition is not a uniquely Kenyan problem: our research has investigated the same issue in South Africa, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. In South Africa, in particular, thousands of state-issued weapons have been lost or stolen over the past decade.40 In Kenya, as the Opiyo case highlights, access to state ammunition fuels some of the most intractable conflicts in the country, including ethnic violence and banditry.

Notes

-

Jenni Irish-Qhobosheane, How to silence the guns? Southern Africa’s illegal firearms markets, GI-TOC, September 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/GITOC-ESA-Obs-How-to-silence-the-guns-Southern-Africas.REV_.pdf, p 1. ↩

-

According to the UNODC, Kenya ranks among the African countries with the highest arms seized linked to trafficking. ‘In Africa, the largest quantities of seized weapons seized were registered in Angola and Kenya,’ the report reveals. See UNODC, Global Study on Firearms Trafficking 2020. Vienna, 2020, https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/Firearms/2020_REPORT_Global_Study_on_Firearms_Trafficking_2020_web.pdf, p 89. In Kenya, civilian possession of weapons is unrivalled by other East African countries; the country has 740 000 illegal firearms – the highest number in unofficial hands in the region. See Duncan E Omondi Gumba and Guyo Chepe Turi, Cross-border arms trafficking inflames northern Kenya’s conflict, Institute for Security Studies, 18 November 2019, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/crossborder-arms-trafficking-inflames-northern-kenyas-conflict. ↩

-

Jenni Irish-Qhobosheane, How to silence the guns? Southern Africa’s illegal firearms markets, GI-TOC, September 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/GITOC-ESA-Obs-How-to-silence-the-guns-Southern-Africas.REV_.pdf.. ↩

-

Interview with George Musamali, a former law enforcement officer, currently security and policy analyst, Nairobi, 13 August 2022. ↩

-

Elizabeth Were, GSU armoury cop detained over 2,000 bullets, The Star, 21 September 2021, https://www.the-star.co.ke/counties/nairobi/2021-09-21-gsu-armoury-cop-detained-over-2000-bullets. ↩

-

Interview with George Musamali, a former law enforcement officer, currently a security and policy analyst, Nairobi, 13 August 2022. ↩

-

Cyrus Ombati, Senior GSU officer arrested over 2,000 bullets seized in Utawala, The Star, 16 September 2021. https://www.the-star.co.ke/counties/nairobi/2021-09-16-senior-gsu-officer-arrested-over-2000-bullets-seized-in-utawala. ↩

-

Zadock Angira, Rogue GSU officer linked to bullets smuggling racket, People Daily, 22 September 2021, https://www.pd.co.ke/news/rogue-gsu-officers-linked-to-bullets-smuggling-racket-95930. ↩

-

Cyrus Ombati, Fears of more clashes as 2,640 bullets are recovered in Laikipia, The Star, 22 August 2021, https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2021-08-22-fears-of-more-clashes-as-2640-bullets-are-recovered-in-laikipia/. ↩

-

Laikipia County is among a dozen or so areas countrywide rocked by conflicts over resources and/or political power. The government has deployed special police or military units to restore peace in these areas. ↩

-

Zadock Angira, Rogue GSU officer linked to bullets smuggling racket, People Daily, 22 September 2021, https://www.pd.co.ke/news/rogue-gsu-officers-linked-to-bullets-smuggling-racket-95930. ↩

-

Cyrus Ombati, GSU instructor murdered, body found in Nairobi quarry, The Star, 24 August 2021, https://www.the-star.co.ke/counties/nairobi/2021-08-24-gsu-instructor-murdered-body-found-in-nairobi-quarry. ↩

-

Cyrus Ombati, Mystery of GSU armoury officer missing in Nairobi, 14 July 2021, https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2021-07-13-mystery-of-gsu-armoury-officer-missing-in-nairobi. ↩

-

Zadock Angira, GSU inspector arrested after bullet cache found in vehicle, People Daily, 17 September 2021, https://www.pd.co.ke/news/gsu-inspector-arrested-after-bullet-cache-found-in-vehicle-94966. ↩

-

Interview with a former officer of the GSU, Nairobi, 28 July 2022. ↩

-

Interview with security analyst, Nairobi, 4 August 2022. ↩

-

Elizabeth Were, GSU armoury cop detained over 2000 bullets, The Star, 21 September 2021, https://www.the-star.co.ke/counties/frica/2021-09-21-gsu-armoury-cop-detained-over-2000-bullets. ↩

-

Zadock Angira, Rogue GSU officer linked to bullets smuggling racket, People Daily, 22 September 2021, https://www.pd.co.ke/news/rogue-gsu-officers-linked-to-bullets-smuggling-racket-95930. ↩

-

Mary Wambui, Banditry: Rogue policemen renting out arms, Nation, 22 March 2022, https://nation.africa/kenya/news/banditry-rogue-policemen-renting-out-arms-3756266. ↩

-

Zadock Angira, Rogue GSU officer linked to bullets smuggling racket, People Daily, 22 September 2021, https://www.pd.co.ke/news/rogue-gsu-officers-linked-to-bullets-smuggling-racket-95930. ↩

-

Giacomo Persi Paoli, Ammunition marking: Current practices and future possibilities, Issue Brief, 3 (2011), Small Arms Survey, https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/sites/default/files/resources/SAS-IB3-Ammunition-Marking.pdf. ↩

-

Interview with a former instructor, Nairobi, 30 July 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a former marksman, Nairobi, 28 July 2022. ↩

-

IPOA is a statutory body that investigates complaints lodged against police officers. It provides for civilian oversight of the force. ↩

-

IPOA, End-term board report, 2012–2018, http://www.ipoa.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/IPOA-BOARD-END-TERM-REPORT-2012-2018-for-website.pdf, p 93. ↩

-

Interview with a police officer, Nairobi, 28 July 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a GSU officer, Nairobi, 15 June 2022. ↩

-

Jacob Walter, Marsabit on red alert as two shot dead amid surge in violence, Nation, 18 April 2022, https://nation.africa/kenya/counties/marsabit/two-shot-dead-in-marsabit-amid-surge-in-violence-3785766. ↩

-

Interview with a security expert, Nairobi, 31 July 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a herder, Marsabit, 28 July 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a senior police officer, Nakuru, 28 July 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a police marksman, Nairobi, 28 July 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a police instructor, Nairobi, 28 July 2022. ↩

-

The Police Reservists is a unit drawing civilians formed to assist the police in maintaining law and order, especially in vast remote areas within little police presence. ↩

-

IPOA, Annual report and financial statements for the year ending 30th June 2019, http://www.ipoa.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IPOA-Annual-Report-2018-2019-Web.pdf, p 15. ↩

-

National Police Service Internal Affairs Unit, Annual Performance Report Year 2020, https://www.iau.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/IAU-2020-ANNUAL-PERFORMANCE-REPORT_compressed-1.pdf, p 22. ↩

-

IPOA, Annual report and financial statements for the year ending 30th June 2019, http://www.ipoa.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IPOA-Annual-Report-2018-2019-Web.pdf, p 15. ↩

-

Interview with security and policy expert George Musamali, 6 August 2022, by phone; interview with a former GSU officer, Nairobi, 28 July 2022. ↩

-

IPOA, End-term board report 2012–2018, http://www.ipoa.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/IPOA-BOARD-END-TERM-REPORT-2012-2018-for-website.pdf, p 122. ↩

-

Jenni Irish-Qhobosheane, How to silence the guns? Southern Africa’s illegal firearms markets, GI-TOC, September 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/GITOC-ESA-Obs-How-to-silence-the-guns-Southern-Africas.REV_.pdf. ↩