Round-tripping, corruption and established smuggling networks: The illegal cigarette trade between Uganda and its neighbouring countries.

While smoking is declining in most of the world, many African countries are high priority for tobacco companies looking to expand their market. Findings from research and monitoring groups – such as the 2022 Tobacco Atlas, which monitors smoking prevalence and industry behaviour worldwide, and Stopping Tobacco Organisations and Products, an industry watchdog – have shown concerted efforts by Transnational Tobacco Companies (TTCs) to market their products and gain influence in African countries.1 Both the production and consumption of tobacco products are shifting from high-income countries to middle- and low-income countries (many of which are in East and southern Africa).2 Importantly, the number of smokers in Africa is increasing, largely driven by the growing population.3

Cigarette smuggling has been an issue in East Africa since late 1990s, with Uganda being a source, transit point and destination for illicit cigarettes.

The strategies adopted by TTCs have a significant knock-on effect on the illicit tobacco market. Elsewhere in Africa and globally, TTCs have been known to take advantage of cigarette smuggling routes where this offers an opportunity for profit.4 An investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) in 2021, for example, revealed how British American Tobacco (BAT) has supplied cigarettes to Mali, knowing that these cigarettes would be destined for trafficking groups in the jihadist-held north of the country.5

‘Whether these companies are directly involved in smuggling is contentious, but what we can say is that they often deliberately leave their supply chains unsecured, making smuggling by other parties easier,’ says Dr Hana Ross, an expert on tobacco control and Principal Research Officer at the Economics of Excisable Products Research Unit at the University of Cape Town.6

TTCs are also widely known to invest considerable resources in shaping the narratives around the illicit tobacco trade, as well as lobbying governments against increasing taxes on tobacco products by arguing that this will increase smuggling.

In Uganda, cigarettes form part of broader smuggling economies. Cigarette smuggling has been an issue in East Africa since at least the late 1990s, with Uganda being simultaneously a source, transit point and destination for illicit cigarettes of various kinds.7 These complex dynamics persist today.

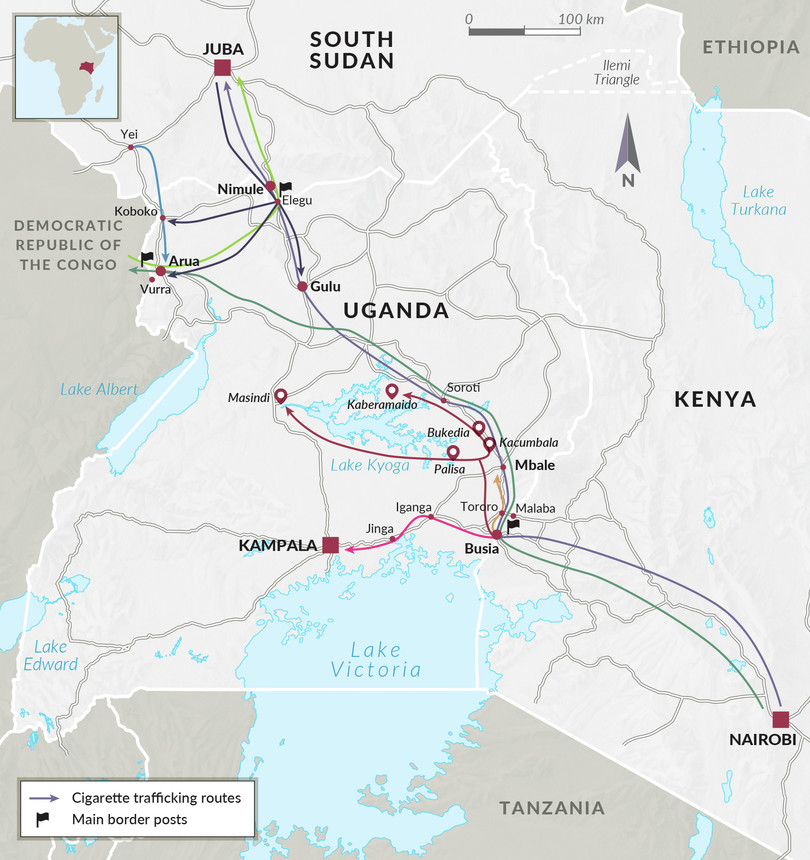

Uganda’s complex cross-border cigarette flows

Figure 1 Cigarette trafficking routes in Uganda.

Uganda has a significant illicit cigarette market. In March 2022, the Uganda Revenue Authority (URA) estimated the cost to Uganda’s economy at 30 billion Ugandan shillings (UGX) (just under US$8 million) in annual revenue from illicit cigarette smuggling alone.8 Between 2014 and 2016, 650 tonnes of tobacco were seized countrywide.9

Available estimates suggest that the illicit market grew during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to URA commissioner Vincent Seruma, between 2019 and 2020, illicit trade in cigarettes increased by 17.4% by the end of the 2020 calendar year, mainly because of the impact of the pandemic.10 BAT Uganda estimated that illicit trade grew 44% over the same period.11 Given the vested interest of companies such as BAT in this area, this may well be an inflated estimate.

Uganda is at the centre of some oddly circuitous smuggling routes, owing to a phenomenon known as ‘round-tripping’. Cigarettes are marked for export from one country to another, meaning that tax is not payable in the country of origin. Instead of being delivered to the intended destination, the stock is smuggled either back to its country of origin or to a third country and sold, illegally, tax free.12

Cigarettes are smuggled into Uganda from neighbouring Kenya along panya routes (smaller, less frequented back roads – panya means ‘mouse’ in Swahili). Smuggled cigarettes travel, mostly by truck,13 from the bustling western Kenyan border town of Busia, until they reach the eastern Ugandan city of Mbale, where part of the consignment is distributed to retailers. Much of the stock remains in Uganda, moved along the major highway at night to the capital, Kampala, and smaller towns along the way. Some are taken further north to districts around the central Lake Kyoga. Some stock crosses the border into either the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) or South Sudan.14

In turn, some of these products find their way back into Uganda.15 As a process, it appears counterintuitive, but the costs of transporting cigarettes in this roundabout fashion are lower than if tax were to be paid on the products, allowing for greater profit to be made. Products manufactured in Uganda are shipped through the DRC and South Sudan, before finding their way back to Uganda.16

According to an official with the URA based at Elegu border post, at the northern border with South Sudan, these smuggling routes from Kenya, through Uganda to the DRC and South Sudan, have been active for years.17

Supermatch in focus: An example of round-tripping in action

Some of these dynamics were laid bare in a long-running, convoluted court dispute between two East African tobacco companies over Supermatch, a popular cigarette brand. Leaf Tobacco – which holds the trademark for Supermatch in Uganda and South Sudan – sued the URA, arguing that Mastermind was ‘illegally transiting Supermatch cigarettes through Uganda and that some of it ends in Uganda’, under the pretext of exporting them to South Sudan.18 Leaf argued that they were suffering losses to their revenues in Uganda, as these cigarettes were being re-exported illegally from South Sudan into Uganda, in the type of round-tripping dynamic described above, and that the URA should prevent their transit through Uganda.

The lawsuit was eventually dismissed, the court finding that Ugandan authorities were obliged under international law to allow the passage of the goods through its territory and that the legality of their entry into South Sudan was a matter for authorities in that country to decide.19 The judge accepted the plaintiff’s claim that Mastermind’s Supermatch cigarettes were often found in Uganda illegally, but decided it could not be proven that it was Mastermind involved in the smuggling.

As one URA regional manager described, ‘South Sudan is another wilderness in administration. Its methods of operation are a mess. On our side, we clear cigarettes at the border (officially) because we cannot stop international business. But we know that most of it will come back into Uganda.’20

Our research found that brands of exported cigarettes from Kenya, officially destined for South Sudan, are found in Uganda. This includes Supermatch,21 confirming the Mastermind brand’s presence and that this smuggling dynamic continues. Ironically, Leaf Tobacco’s Supermatch cigarettes, produced in their facility in Yei, South Sudan, are also reportedly routinely smuggled into Uganda.22

A store selling smuggled cigarettes in Koboko Town, Uganda.

Photo: supplied

How cigarettes form part of broader smuggling economies

In regions such as Arua, a town in north-western Uganda near the borders with the DRC and South Sudan, and Elegu, a border post with South Sudan, cigarettes form part of broader smuggling economies. Armed conflict and insecurity in Uganda and its neighbours and links between communities across national borders have played a role in creating this smuggling economy. Communities living along the borders of Uganda, South Sudan23 and the DRC24 have relied on informal trade, and each other, during times of conflict.25

Other commodities smuggled along the same routes and by the same networks include fuel. ‘It takes two to three weeks to accumulate money to buy a motorcycle when smuggling cigarettes, but this must be alternated with fuel, which makes quicker money and is less detectable,’ explained one smuggler.26 ‘Fuel smuggling is widespread because people depend on it,’ he added.27

Muto,28 a taxi operator in Koboko, near the DRC border, occasionally participates in smuggling cigarettes and fuel from South Sudan to Uganda. His three brothers smuggle cigarettes and fuel from South Sudan to Koboko, from where they distribute. On a good day, Muto makes a turnover of UGX1.5 million to UGX3 million (roughly US$400 to US$800) from between three and five round trips from Morobo to Koboko, using panya routes interlinking the countries. Boda boda (motorcycles) are commonly used.29 Muto’s younger brother, with four years’ experience in smuggling, explained that transport is inexpensive. When using agents, it costs 2 500 Sudanese pounds (US$19.20) from Juba to Yei, 1 500 South Sudanese pounds (SSP) (US$11.50) from Yei to Kaya, and UGX15 000 (US$4) from Kaya to Koboko town.30

‘Box trucks’ – transport vehicles with sealed cabins – with special compartments created inside to hide cigarettes are used to cross the border.31 Modified vans, with seats removed, are also used to transport contraband. URA presence along the Elegu–Atiak highway, which runs for 36.5 kilometres in a southerly direction from the border to Atiak town,32 is high, and close to a dozen arrests occur daily. However, cases are rarely opened and no attempts at prosecution are made due to systemic corruption.33

These smuggling networks sometimes use weapons and violence to defend their interests. Nahori Oyaa, the Resident District Commissioner of Arua, noted that tax officials stationed at border towns face intimidation by smugglers, some of whom carry firearms.34 Violent incidents have occurred. In Koboko District, in respective incidents in 2019 and 2021, URA offices were torched in protest at the impounding of smuggled goods.35 A recall of URA personnel often follows events like these. Smugglers use this time to restock, and revenue is lost through non-collection before officials are redeployed.36

Smuggling routes cross the Unyama River to Elegu, where handover to intermediaries takes place.37 The intermediaries then sell to dealers. According to a local official at the border post, the smugglers work at night, often using panya roads, and are always armed (often with AK-47s).38 Syndicates allegedly have contacts in government departments of Immigration, Revenue and Border Security, used for facilitating the uninhibited flow of illicit goods.39 Before transportation, smugglers contact acquaintances within the URA overseeing the issuance of permits to ensure safe passage of smuggled goods through bribery.40

‘Can you imagine even bribes of UGX10 000 [US$2.66] is received by these people,’41 said one community leader in Elegu, decrying law enforcement attitudes.42 South Sudanese smugglers who move cigarettes into Uganda pay bribes to border/security authorities of between SSP2 500 (US$19.20) and SSP5 000 (US$38.40) depending on the size/quantity of merchandise, according to a journalist based in Elugu.43 That such small amounts are accepted demonstrates the systemic nature of corruption and the ease with which border officials can be bribed. This gives an indication of the extent of non-enforcement of border controls and how smuggling is normalized along the border.

Nyeko Geoffrey, a community leader in Elegu, argued that law enforcement is carried out ‘selectively’ with respect to smuggling.44 A dealer operating between Elegu and Nimule (a border town on the South Sudan side) remarked, ‘If you are arrested with cigarettes or fuel, your goods and motorbike are confiscated, you are asked to pay fines, but then your goods are sold by the enforcement officials [URA] for their personal gain. They are in business, not law enforcement.’45

‘It is not about to end,’ the District Local Government Chair for Arua, Cosmas Iyikobwe, remarked, citing the number of youths engaged in various criminal activities, including brokering illicit flows of goods.46 Iyikobwe also referred to the limited level of social cooperation in the fight against organized crime, as civilians distrust the state. The region allegedly loses more than UGX1 billion (approximately US$265 500) in revenue to smuggling, lamented Moses Obeta, chairperson of the business community in Arua District.47

How the focus on taxation ignores other drivers of the illicit cigarette trade

The tobacco industry often argues that high taxation on tobacco products drives the illicit trade.48 This is despite the proven efficacy of excise increases in curbing smoking prevalence and illicit trade.49 In Uganda, a 2019 study estimated that smoking prevalence drops between 2.6% and 3.3% for every 10% increase in price.50 Furthermore, global research indicates that prices of illicit cigarettes also tend to increase with price increases in the legal market.51 Research further demonstrates that illicit trade is generally higher in countries where legal cigarettes are cheaper.52

In 2015, Uganda introduced new legislation, the Tobacco Control Act 2015, which increased the excise tax on cigarettes to 40% of the cost price, banned smoking in public places, and raised the minimum smoking age to 21.53 The legislation has been credited with helping reduce the prevalence of smoking in Uganda. The legislation came under attack from the tobacco lobby, with BAT going as far as taking the Ugandan government to court in an attempt to declare the Act unconstitutional.54 The court found against BAT, but this is nonetheless an example of industry attempts to undermine tobacco control.

Evidence from regions such as Arua and Elegu border post demonstrates how tax is just one factor among many shaping the illicit trade in cigarettes. Cross-border demand for consumer goods, corruption, insecurity and professionalized, armed smuggling networks mean a vibrant smuggling market persists.

Ugandan authorities have made moves to counter the illicit cigarette trade, including by introducing a form of digital tax stamp system in 2019, which traces excisable products from manufacture to sale, to curtail smuggling;55 conducting operations to seize shipments of illicit cigarettes; and, as of April 2022, commissioning 245 Uganda People’s Defence Force attachés for anti-smuggling operations, working with the police.56 Yet corruption continues to facilitate the smuggling of cigarettes and other goods.

Notes

-

Rachel Kitonyo and Jeffrey Drope, Africa will be the world’s ashtray if big tobacco is able to get its way, The Guardian, 2 June 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/commentisfree/2022/jun/02/tobacco-smoking-africa-worlds-ashtray-acc. ↩

-

Adriana Appal et al., Explaining why farmers grow tobacco: Evidence from Malawi, Kenya, and Zambia, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 22, 12 (2020), 2238–2245. Land area under cultivation for tobacco farming increased by 3.4% in sub-Saharan Africa between 2012 and 2018, and 90.43% of this tobacco is cultivated in East Africa; see World Health Organization, Status of tobacco production and trade in Africa, 2021, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240020009. ↩

-

Eric Crosbie et al., Tobacco supply and demand strategies used in African countries, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 99, 7 (2021), 539–540. ↩

-

Telita Snyckers, Dirty Tobacco: Spies, Lies and Mega-Profits. Cape Town: Tafelberg Publishers, 2020. ↩

-

Aisha Kehoe Down, Gaston Sawadogo and Tom Stocks, British American Tobacco fights dirty in West Africa, OCCRP, 26 February 2021, https://www.occrp.org/en/loosetobacco/british-american-tobacco-fights-dirty-in-west-africa. ↩

-

Interview with Dr Hana Ross, Principal Research Officer at the Economics of Excisable Products Research Unit at the University of Cape Town, 27 July 2022, by phone. ↩

-

Kristof Titeca, Luk Joossens and Martin Raw, Blood cigarettes: Cigarette smuggling and war economies in central and eastern Africa, Tobacco Control, 20, 3 (2011), 226–237. ↩

-

The Taxman, URA intensifies crackdown against illicit cigarette trade, 23 March 2022, https://thetaxman.ura.go.ug/ura-intensifies-crackdown-against-illicit-cigarette-trade. ↩

-

Dorothy Nakaweesi, Uganda loses Shs200b to cigarettes smuggling, Daily Monitor, 11 April 2018, https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/business/finance/uganda-loses-shs200bto-cigarettes-smuggling–1750228. ↩

-

Interview with Vincent Seruma, URA Commissioner Public Affairs and Cooperate Communications, Kampala, October 2021, by phone. ↩

-

Martin Luther Oketch, Cigarettes smuggling eats into Batu’s earnings, Daily Monitor, 31 May 2021, https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/business/finance/cigarettes-smuggling-eats-into-batu-s-earnings-3420824. ↩

-

Michael McLaggan, When the smoke clears: The ban on tobacco products in South Africa during COVID-19, GI-TOC, September 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/When-the-smoke-clears-The-ban-on-tobacco-products-in-South-Africa-during-Covid19-GI-TOC.pdf. ↩

-

Interview with Daily Monitor journalist David Ochieng, Busia Town, 28 February 2022. ↩

-

Interview, with a police officer from the Enforcement Unit, Mbale Town, 2 March 2022. ↩

-

Interviews with a former ambassador, Arua, December 2021. ↩

-

Kristof Titeca, Luk Joossens and Martin Raw, Blood cigarettes: Cigarette smuggling and war economies in central and eastern Africa, Tobacco Control, 20, 3 (2011), 226–237; interviews with a former ambassador, Arua, December 2021. ↩

-

Interview with a senior URA customs official at Elegu border post, 4 July 2022, by phone. ↩

-

Leaf Tobacco and Commodities Uganda Limited v Commissioner of Customs, Uganda Revenue Authority & Another (HCCS 218 of 2012) (2019), UGCommC 7, 21 March 2019, https://ulii.org/ug/judgment/commercial-court-uganda/2019/7. ↩

-

Leaf Tobacco and Commodities Uganda Limited v Commissioner of Customs, Uganda Revenue Authority & Another (HCCS 218 of 2012) (2019), UGCommC 7, 21 March 2019, https://ulii.org/ug/judgment/commercial-court-uganda/2019/7. ↩

-

Discussion with URA Regional Manager West Nile Region, 21 July 2022, by phone. ↩

-

Research team conclusion based on field experiences between 2020 and 2021. ↩

-

Interview with a senior URA official, Gulu, 28 May 2022. ↩

-

‘Southern Sudan’ is referred to here as the region that was part of the sovereign territory of Sudan until 2011. ↩

-

Kristof Titeca and Rachel Flynn, Hybrid governance, legitimacy and (il)legality in informal cross-border trade in Panyimur, northwest Uganda, African Studies Review, 57, 1 (2014), 71–91. ↩

-

Interview with a dealer, Koboko, December 2021. ↩

-

Interview with a smuggler (cigarettes and fuel), December 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Not his real name. ↩

-

Interview with Nahori Oyaa, Resident District Commissioner in Arua, 28 February 2020. ↩

-

Interview with two dealers (brothers), Koboko, December 2021. The major routes used by boda boda are: Morobo (in South Sudan) to Arua through Arirwara (DRC) and Salia Musala (in Koboko, Uganda); Morobo to Arua through Kimba and Busia; and Kerwa to Yumbe through Madigo. ↩

-

Interview with Daily Monitor journalist, Kampala, 18 February 2022. ↩

-

Google Maps, https://goo.gl/maps/jb4LKKwWxPB724MBA. ↩

-

Interview with community leader, Elegu, December 2021; interview with a radio network journalist, December 2021. ↩

-

Interview with Resident District Commissioner, Arua, 28 February 2020. ↩

-

Interview with Chandia Stephen, URN Journalist and West Nile Press Association, 21 July 2022, by phone. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with an official assigned to assist the Resident District Commissioner in the COVID-19 Task Force, Amuru District, Elegu border post, December 2021. The COVID-19 Task Force was a special committee appointed by the president in different districts to oversee government and presidential directives in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. ↩

-

Interview with COVID-19 Task Force member, Amuru District, Elegu border post, December 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with community leader Okumu Santo, Elegu, December 2021. ↩

-

Interview with community leader Okumu Santo, Elegu, December 2021. ↩

-

Interview with journalist based in Elegu, 22 February 2022, by phone. ↩

-

Interview with community leader (security and defence) Nyeko Geofrey, Elegu, December 2021. ↩

-

Interview with a dealer, Elegu border, December 2021. ↩

-

Interview with District Local Government Chair, Arua, 2 March 2020. ↩

-

Interview with business community leader of Arua, 22 February 2022, by phone. ↩

-

Guillermo Paraje, Michal Stoklosa and Evan Blecher, Illicit trade in tobacco products: Recent trends and coming challenges, Tobacco Control, 31, 2 (2022), 257–262; Catherine Egbe et al., Landscape of tobacco control in sub Saharan Africa, Tobacco Control, 31, 2 (2022), 153–159; Nicole Vellios, Hana Ross and Anne-Marie Perucic, Trends in cigarettes demand and supply in Africa, PLoS ONE, 13, 8 (2018). ↩

-

International Agency for the Research on Cancer (IARC), Effectiveness of tax and price policies for tobacco control, IARC Handbooks of Cancer prevention in Tobacco Control, vol 14. Lyon, France: IARC, 2011. ↩

-

Grieve Chelwa and Corné van Walbeek, Does cigarette demand respond to price increases in Uganda? Price elasticity estimates using the Uganda National panel survey and Deaton’s method, BMJ Open, 9 (2019). ↩

-

Guillermo Paraje, Michal Stoklosa and Evan Blecher, Illicit trade in tobacco products: Recent trends and coming challenges, Tobacco Control, 31, 2 (2022): 257–262. ↩

-

Luk Joossens and Martin Raw, From cigarette smuggling to illicit tobacco trade, Tobacco Control, 21, 2 (2012), 230–234. ↩

-

Uganda Tobacco Control Act of 2015. ↩

-

Kenneth Kazibwe, Court blasts BAT Uganda as petition against Tobacco Control Act is thrown out, The Nile Post, 28 May 2019, https://nilepost.co.ug/2019/05/28/court-blasts-bat-uganda-as-petition-against-tobacco-control-act-is-thrown-out. ↩

-

The Taxman, URA intensifies crackdown against illicit cigarette trade, 23 March 2022, https://thetaxman.ura.go.ug/ura-intensifies-crackdown-against-illicit-cigarette-trade. ↩

-

Mary Karugaba, Uganda Tightens grip on smuggling, deploys more security personnel, New Vision, 17 April 2022, https://www.newvision.co.ug/articledetails/131890/undefined. ↩