Farmers and herders increasingly targeted as kidnapping for ransom reaches record levels in Cameroon’s Nord region.

As midnight approached on 17 May 2023, unidentified armed men stormed into the northern Cameroonian village of Lagoye and kidnapped Babana, a 52-year-old farmer.1 His kidnappers demanded a ransom payment of FCFA15 million (approximately €22 660). After his family paid the ransom, he was freed, having spent almost two weeks in captivity. Babana’s ordeal is just one of many kidnapping incidents to have taken place in Touboro, the district in the Nord region’s easternmost department of Mayo-Rey in which Lagoye is situated. Touboro, however, is not alone. Since 2020, across the country’s Nord region, particularly in the departments of Mayo-Rey and Benoué, there has been a substantial increase in the number of individuals kidnapped (see Figure 1).

In January 2023, a record 46 hostage-taking incidents were reported in just two days in Cameroon’s Nord region.2 Based on the number of people kidnapped in the first five months of 2023 (see Figure 2), it is likely that this year’s figures could surpass those of last year. Although the country’s Extrême-Nord region faces a violent extremist threat from the two main Boko Haram factions, Islamic State West Africa Province and Jama’tu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad (People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad),3 in the Nord region the threat is of a different nature. Residents are being targeted by a diverse set of criminal actors seeking to exploit the substantial profit-making potential of kidnapping for ransom.

Although the primary source of funding for these criminal actors, known as zaraguinas, used to be operating as coupeurs de route (highway robbers) and subsequently cattle rustlers, a combination of factors led to their growing diversification into kidnapping for ransom.4 Despite military operations against the zaraguinas having delivered moderate gains in the Nord region in 2022, the history of criminality in northern Cameroon suggests that military pressure is likely to merely geographically displace the violence or catalyze a transformation in the criminal dynamics of the region. The resurgence of violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo since mid-2022; the development of rebel factions in south-western Chad; the rise of communal violence in Cameroon; and the volatile security context in Sudan all contribute to varying degrees to the spread of weapons and reinforcement of criminal activities, and are only going to worsen the situation in Cameroon.5

Figure 1 Kidnapping incidents in Cameroon’s Nord region, 2019–2023.

Note: Data for 2023 is as of the end of May.

From coupeurs de route and cattle rustlers to kidnappers

The zaraguina phenomenon emerged in the Central African Republic (CAR) in the 1980s.6 As demobilized or disaffected soldiers and mercenaries proliferated against the backdrop of the various security crises in CAR, Chad and Sudan, they brought strength in numbers – and weapons – to the zaraguinas. This provided the zaraguinas with a significant degree of professionalization, supporting their spread into northern Cameroon, aided in large part by porous borders and the greater economic opportunity afforded by the prominence of the livestock sector in the region.7 The bandits, known for their ruthless violence, would ambush individuals travelling on their way to or from cattle markets carrying large sums of money, by barricading roads with tree trunks.8

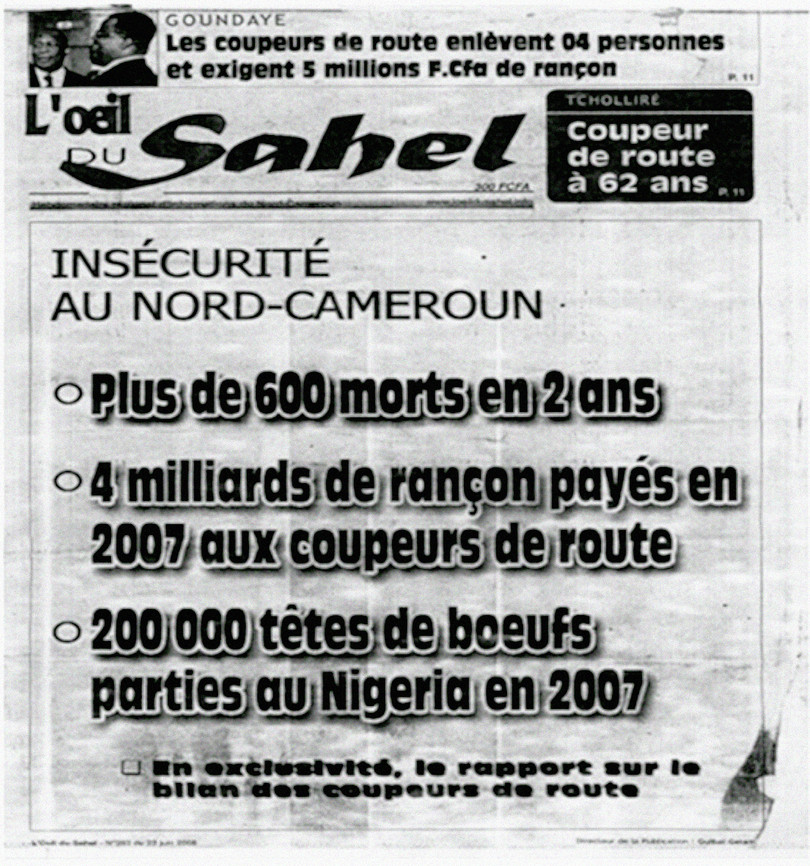

Illustration of the scale of the ransom paid to hostage-takers in northern Cameroon in 2007.

Photo: L’œil du Sahel n° 293, 23 June 2008.

The disjointed – and as a result, largely failed – responses to the zaraguinas by authorities in Cameroon, CAR and Chad allowed another threat to emerge: cattle theft.9 The presence of large livestock markets in the border regions of the other Lake Chad Basin countries, namely, Nigeria, Niger and Chad, was a key enabler of cattle theft in Cameroon, as these markets provided the opportunity to quickly sell off the stolen animals. Stolen cattle were smuggled by networks across the notoriously porous borders in the region to consumers in Nigeria, Chad and CAR, and from these countries into Cameroon.

By the turn of the century, the Cameroonian armed forces had introduced measures aimed at disrupting the rampant road ambushes and widespread cattle rustling, including establishing a greater number of roadblocks and checkpoints. They also provided military escorts for herders travelling along transhumance corridors towards southern and north-east Cameroon, and Chad, for example, as well as for groups of traders on their way to and from cattle markets. As cattle rustling became an increasingly complicated activity for the criminal actors to carry out, they began turning to kidnapping for ransom instead.10 Taking people hostage is a simpler endeavour than stealing livestock, as it is easier to move into villages inconspicuously, it can be done at night, and is easier to hide.

By 2003, kidnapping for ransom had become a priority concern for Cameroonian policymakers and security services. Today, the kidnapping for ransom industry generates around FCFA1 billion (approximately €1.5 million) a year across northern Cameroon, according to local media and civil society organizations, and has become the primary security threat facing the Nord region.11

Violent kidnappings intensify

The capacity for violence and the ruthlessness of the perpetrators of kidnappings in northern Cameroon should not be underestimated. Benoué is the department in the Nord region with the second-highest number of individuals kidnapped since 2019, after Mayo-Rey.12 On 13 March 2023, farmland belonging to two agropastoralists in Bibémi district, Benoué, was targeted by six armed men. The attackers took three children hostage. Seven days later, the children were brutally executed due to the families’ failure to pay the ransom, set by the kidnappers at FCFA18 million (around €27 000).13 A few weeks later, in the early hours of 3 April, in the town of Tchéboa, an 18-year-old was kidnapped by unidentified armed men, who demanded a ransom of FCFA10 million (approximately €15 200).14

In 2020 there was an increase in kidnapping for ransom activity in the Mayo-Rey department, which borders Chad and CAR (see Figure 2). This occurred in parallel to the reignition of violence in CAR. By the end of 2022, following three consecutive year-on-year increases, the number of people kidnapped in Mayo-Rey had almost doubled since 2019, from 103 to 194.15

Figure 2 Number of people kidnapped in the Nord region of Cameroon, by department, 2019–2023.

Note: Data for 2023 is as of the end of May.

Mayo-Rey is rich in pastures, attracting livestock farmers from other regions of Cameroon as well as neighbouring countries. However, given the lucrative nature of the cattle market in the region, herders are among the people most targeted by kidnappers. In February 2023, Mal Oumarou, a herder living in Madingring, in Mayo-Rey, was taken hostage, with his captors demanding a ransom of FCFA20 million (about €30 500).16

A wealthy cattle trader based in Touboro paid more than FCFA30 million (approximately €46 000) when his son was kidnapped in June 2020. Before paying the ransom, he reported the kidnapping to a local law enforcement official. However, this was in vain. ‘The hostage-takers called me and repeated exactly what I had told the [official],’ he said. ‘I realized that I was trapped, and I just paid them so that they wouldn’t kill him.’17

Examples of complicity between hostage-takers and law enforcement officials are plentiful in northern Cameroon. As a result, there is a strong reluctance to report kidnapping cases to the authorities. The alleged involvement of local law enforcement is also considered a key driver of the increase in kidnapping incidents since 2020. While there has always been a degree of collaboration, it is perceived by close observers to be significantly more flagrant nowadays.18

However, alleged collusion between criminals and local authorities is not the only reason the families of kidnapping victims largely refrain from coming forward. Families of those held for ransom report that kidnappers threaten to kill hostages if they contact the security and defence forces. As such, families are forced to remain silent and negotiate directly with the criminals, or risk reprisals. ‘Who is going to leave their mother, wife, father or children in the hands of a criminal on the pretext that there is no point paying the ransom when they’ll never be freed? My mother was freed after a ransom of FCFA17 million [€26 000] was paid,’ said a local farmer in Touboro whose mother was kidnapped in March 2023.19

Despite a seemingly disproportionate number of them taking place in Touboro, kidnapping incidents occur in a number of different places in the Nord region. Perpetrators capture individuals using roadside ambushes or by making night-time incursions into villagers’ homes. Abductions are so common that not even town centres are safe. As one Touboro resident reported, ‘Town centres used to be spared [from kidnapping incidents] and so were used as refuges for people fleeing villages, but today that’s no longer the case. Today we live in fear.’20

| Date | Target | Location | Department | Ransom |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| August 2016 | Cotton farmer | Bitou (Touboro) | Mayo-Rey | FCFA 100 million (€150 000) |

| June 2017 | Butcher | Touboro | Mayo-Rey | FCFA 40 million (€61 000) |

| June 2020 | Cattle trader's son | Touboro | Mayo-Rey | FCFA 30 million (€46 000) |

| October 2020 | Farmer's children | Madjolé | Benoué | FCFA 15 million (€22 660) |

| February 2023 | Herder | Madingring | Mayo-Rey | FCFA 20 million (€30 500) |

| February 2023 | Cotton farmer | Laodjougoy | Mayo-Rey | FCFA 6 million (€9 100) |

| March 2023 | Herder's mother | Touboro | Mayo-Rey | FCFA 17 million (€26 000) |

| March 2023 | Farmer's children | Laodjougoy | Mayo-Rey | FCFA 18 million (€27 000) |

| April 2023 | Farmer | Tchéboa | Benoué | FCFA 10 million (€15 200) |

| May 2023 | Farmer | Lagoye (Touboro) | Mayo-Rey | FCFA 15 million (€22 660) |

Figure 3 Selected kidnapping incidents in Cameroon’s Nord region, 2016–2023.

Note: Systematic data collection on the value of ransom payments was not possible. Anecdotal evidence suggests ransom payments range between FCFA10–FCFA30 million (€15 000–€45 000), but the amount demanded by hostage-takers is highly erratic and varies considerably depending on the target’s ability to pay.

While initially targeting cattle herders, kidnappers have since around 2019 expanded their targets to include farmers, given the prosperity of many, particularly cotton farmers.21 In February 2023, a cotton farmer named Vakama was abducted in Laodjougoy, a small village 50 kilometres south of Madingring in Mayo-Rey department. He was freed six days later once his family had paid the ransom of FCFA6 million (approximately €9 100).22

Today, for fear of being kidnapped or murdered, thousands of herders and their families have sold their livestock and moved elsewhere. Others have changed jobs altogether, embracing new professions such as transport and trade in basic foodstuffs, among others, industries that are far less lucrative than the livestock sector.23

The proliferation of kidnapping for ransom has thus contributed to a gradual dislocation of the rural economy, in the Nord region but also in northern Cameroon more broadly, underpinned by people abandoning rural areas in favour of town centres, which are still relatively more stable, even if not entirely safe. Because of the more difficult living conditions these villagers face in urban areas, they are often forced to resort to crime, from minor misdemeanours such as pickpocketing to burglary and even physical assault, to survive. Consequently, this rural exodus has not only reinforced the high cost of living in large cities but has contributed to the development of urban insecurity.

The role of military operations

Despite the escalation of the phenomenon, there have been some successes in the response to kidnapping for ransom in northern Cameroon, with two military operations taking place in 2022. Between 25 April and 30 May 2022, following a spike in kidnapping incidents in Touboro, authorities launched Operation Clean Touboro 1. Comprising 300 members of the Bataillon d’Intervention Rapide (Rapid Intervention Battalion, BIR), an elite unit of the Cameroonian armed forces created to tackle the threat of terrorism and armed groups, Operation Clean Touboro 1 made some gains against kidnapping, displacing criminal actors from the northern flank of the district. Having pushed the criminals southwards, the BIR undertook Operation Clean Touboro 2 from 15 June to 20 July 2022. According to sources from the BIR, the two operations resulted in the liberation of 18 hostages, the arrests of 27 suspects, the killing of four suspected criminal actors and the seizure of a wide range of weapons and ammunition, among other equipment.24

To respond specifically to the kidnapping of farmers, particularly those in the cotton industry, authorities ran Operation Safe Harvest between September and November 2022 to coincide with the harvest period. Although all 21 units of the BIR across the north took part, the operation was concentrated primarily in Mayo-Rey, given its status as the main cotton-harvesting area. Thanks to this operation, farmers in the region were afforded a degree of safety and security when carrying out their harvests. As the president of a local group of cotton farmers in Mayo-Rey said, ‘At last this past year we were able to harvest and sell our cotton without a farmer or a member of a farmer’s family being kidnapped.’25

Regardless of these gains, kidnapping for ransom remains a major security threat across a large section of Cameroon’s Nord region. Although the government’s initial responses to the coupeurs de route were relatively effective, they precipitated a displacement effect, with the increased law enforcement and security service repression in the region driving a different form of criminality. This raises questions around the limitations of securitized approaches to illicit economies such as kidnapping for ransom and highlights the need for alternative strategies that address the drivers of insecurity to accompany such responses.

Notes

-

The victim’s name has been changed to protect his identity. Interview with an intelligence officer of the 4th Rapid Intervention Battalion, Garoua, June 2023. ↩

-

Interview with a local journalist, Garoua, February 2023. ↩

-

Observatory of Illicit Economies in West Africa, ISWAP’s extortion racket in northern Cameroon experiences growing backlash from communities, Risk Bulletin, Issue 7, GI-TOC, April 2023, https://riskbulletins.globalinitiative.net/wea-obs-007/04-iswaps-extortion-racket-in-northern-cameroon.html. ↩

-

The term zaraguina may have its origins in the Chadian Arabic word zarâg (an indigo fabric), referring to the blue that was ‘used to mark the faces of robbers caught red-handed in the markets’. See International Crisis Group, Armed groups in the Central African Republic, Central African Republic: The roots of violence (2015), 2–15; and Christian Seignobos, The phenomenon of the zaraguina in northern Cameroon. A crisis of Mbororo pastoral society, Afrique contemporaine, 239, 3 (2011), 35–59. ↩

-

DW, Chadian power again threatened from the south of the country, 24 January 2023, https://www.dw.com/fr/le-pouvoir-tchadien-de-nouveau-menac%C3%A9-depuis-le-sud/a-64495244. ↩

-

International Crisis Group, Armed groups in the Central African Republic, Central African Republic: The roots of violence (2015), 2–15. ↩

-

Since their emergence in the 1980s, the zaraguinas have comprised a mixture of different profiles, including former soldiers from CAR, Chad, Sudan and Cameroon; mercenaries from rebel groups operating in the region; former herders who had their cattle stolen, and opportunistic and disaffected youth. Interview with an army intelligence officer, Garoua, June 2022. See also International Crisis Group, Armed groups in the Central African Republic, Central African Republic: The roots of violence (2015), 2–15. For a detailed overview of the zaraguina phenomenon in northern Cameroon, see Christian Seignobos, Le phénomène zargina dans le nord du Cameroun: Coupeurs de route et prises d’otages, la crise des sociétés pastorales mbororo, Afrique Contemporaine, 3 (2011), 239, 35–59. ↩

-

Interview with an army intelligence officer, Garoua, June 2022. ↩

-

Interview with a local journalist, Garoua, February 2023. ↩

-

Interview with a local journalist, Garoua, April 2023. ↩

-

Northern Cameroon comprises the three northernmost regions of Extrême-Nord, Nord and Adamaoua. Interview with a member of civil society, Garoua, April 2023. ↩

-

Data provided by sources from Cameroon’s security services. ↩

-

Interview with an officer of the 4th Rapid Intervention Battalion, Garoua, April 2023. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Data provided by sources from Cameroon’s security services. ↩

-

Interview with an officer of the 4th Rapid Intervention Battalion, Garoua, April 2023. The hostage was freed after the Rapid Intervention Battalion intervened. ↩

-

Interview with a local herder, Touboro, June 2020. ↩

-

Interview with an officer of the 4th Rapid Intervention Battalion, Garoua, April 2023. This view is also shared by others, including local journalists reporting on security issues in northern Cameroon. ↩

-

Interview with a local farmer, Touboro, May 2023. Cameroonian authorities formally prohibit the payment of ransom due to the belief that it encourages criminal activity and enables criminals to buy weapons. ↩

-

Interview with a local resident, Touboro, May 2023. ↩

-

Mayo-Rey is a major cotton-growing area, providing resources for the cotton development company SODECOTON, which remains among the most important industries in northern Cameroon. The cotton industry underwent significant reform which allowed the sector to boom from 2019. ↩

-

Interview with a local journalist, Garoua, April 2023. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with an officer of the 4th Rapid Intervention Battalion, Garoua, April 2023. ↩

-

Interview with the president of the cotton farmer common initiative group, Touboro, June 2023. ↩