The Organised Crime Index Africa 2021 underscores differing relationships between certain illicit markets and instability

The Organised Crime Index Africa 2021 provides an analytical framework for understanding the relationship between illicit economies and conflict dynamics. The findings of the 2021 Index show that countries exhibiting the highest levels of criminality are overwhelmingly those experiencing conflict or states of fragility.1 Of the 10 African countries with the highest criminality scores, the majority are enduring conflict or other forms of violence, such as insurrection, terrorist activity or civil unrest.2

West Africa and the Sahel face a high threat from criminal markets, with over three-quarters (77.6%) of citizens residing in countries with high rates of criminality, according to the Index.3 Across the continent, only East Africa, with a score of 5.66, has higher levels of criminality than West Africa (5.47), a reflection of the broad range of illicit markets and criminal actors operating throughout the West African region.

Furthermore, despite some hope that the COVID-19 pandemic would impede organized-criminal activity, criminality levels in Africa have actually increased (by 0.20). In West Africa, as many countries have become less peaceful,4 criminality levels in the region have increased in the time since the publication of the 2019 Organised Crime Index Africa, albeit marginally (by 0.19). This is in line with continental trends.5 The availability of data two years apart, in the form of the 2019 and 2021 indexes, offers insights into the potential causes of heightened levels of criminality on the continent. In West Africa, the continued growth of the cocaine trade, which increased by 0.80 between 2019 and 2021, is a clear driver of greater criminality. Indeed, the pandemic is considered to have aided the drug trade in the region. Drug traffickers in Niger, for example, fearing being targeted by armed groups in southern Libya, have taken advantage of the reduced number of vehicles travelling across the Ténére Desert to increase their flows.6

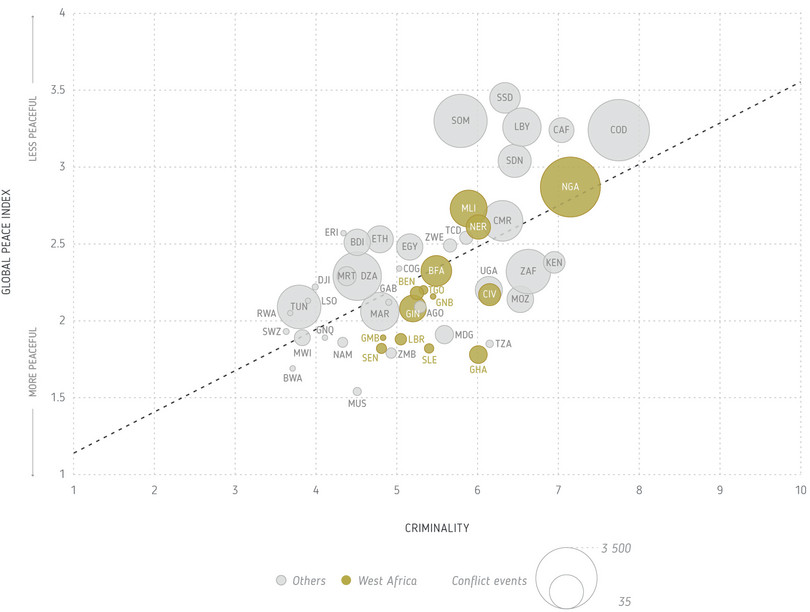

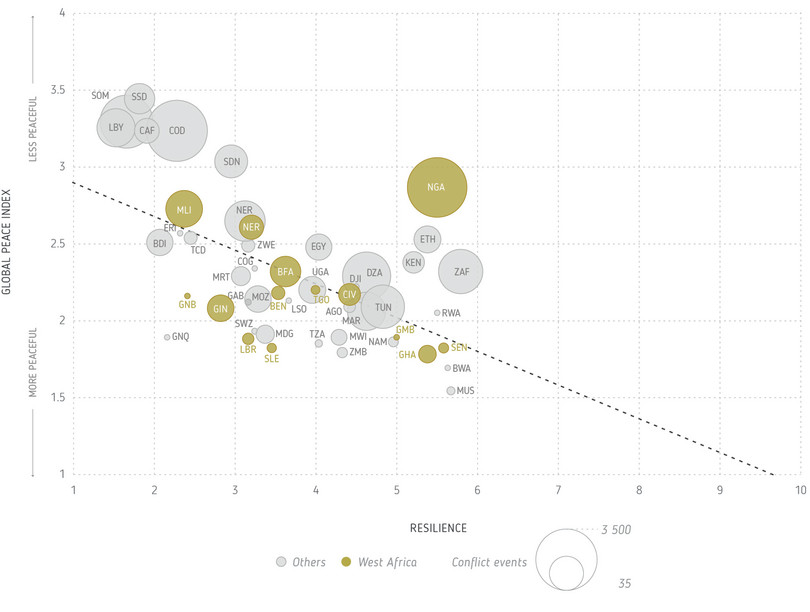

The Index findings also provide a new framework for exploring the long-researched relationship between instability and conflict. It has been well established that illicit economies contribute to long-term enabling environments for instability by prolonging conflict and eroding government responses to violence. In places where conflict, instability and illicit economies are entrenched, development and political power deficits often arise, which can perpetuate the cycle of crime and conflict.7 The metrics for criminality that the Index provides point to a statistical underpinning for this relationship, demonstrating a strong negative correlation between criminality and peacefulness, as measured by the Global Peace Index (GPI) (see Figure 8). In other words, the less peaceful a country, the more likely it is to be plagued by high levels of organized crime. 8

Figure 8 Relationship between criminality and peacefulness.

Organised Crime Index Africa 2021; Vision of Humanity (Institute for Economics and Peace); Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project

What is the Organised Crime Index?

The Organised Crime Index, now in its second iteration, captures levels of organized crime (‘criminality’) and levels of resilience to organized crime (‘resilience’) in 54 countries across Africa.

The Index draws on expert assessments to create two headline scores: criminality and resilience, each measured on a scale of 1 to 10 (where 1 is good and 10 is bad for criminality, and vice versa for resilience).

The criminality score is based on two sub-components: criminal markets and criminal actors. There are 10 criminal markets assessed under the first sub-component: human trafficking, human smuggling, arms trafficking, flora crimes, fauna crimes, crimes related to non-renewable resources, the cocaine trade, the heroin trade, the cannabis trade and the synthetic-drugs trade. Four types of criminal actor are also captured in the Index: mafia-style groups, criminal networks, state-embedded actors and foreign actors.

The resilience component comprises 12 ‘building blocks’ of resilience: political leadership and governance, government transparency and accountability, international cooperation, national policies and laws, judicial system and detention, law enforcement, territorial integrity, anti-money laundering, economic regulatory capacity, victim and witness support, prevention, and non-state actors.

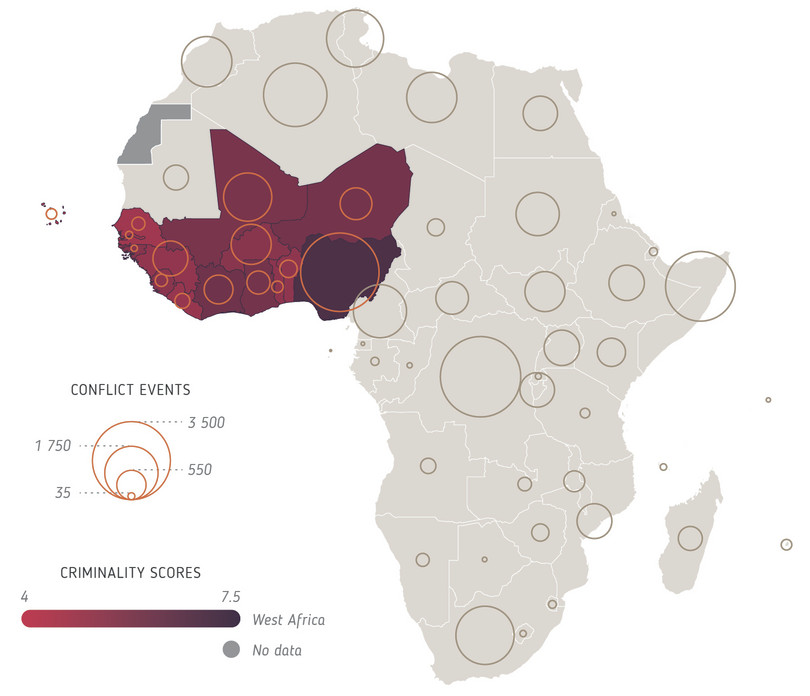

Figure 9 Conflict events and country criminality scores across West Africa.

Organised Crime Index Africa 2021 and Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project

The relationship between illicit-market types and conflict

Not all criminal markets have the same relationship to conflict and instability. Although certain forms of organized crime have clear and unambiguous links to instability, the impact of other illicit economies on conflict dynamics may be more indirect; and in the case of some illicit markets, there may be no discernible link at all.

The global results of the Index show that most criminal markets have some negative correlation with peace and stability, as measured by the GPI. However, arms trafficking (-0.68) and human trafficking (-0.64) stand out as markets with particularly strong relationships with conflict and instability. This becomes even more marked when considering only the 54 African countries included in the Index, in which arms trafficking and human trafficking illustrate particularly strong negative correlations with peace (-0.82 and -0.69, respectively). However, while it is clear that a relationship exists between the two illicit markets and instability, the nature of this relationship differs significantly between countries.

Accelerant illicit markets: Arms trafficking

The arms-trafficking market is a prime example of an accelerant illicit market – i.e., a criminal market that fuels armed violence and conflict, contributes to the fragmentation of conflict, increases the number of criminal groups involved, and heightens the role of violence as a vehicle for market control.9 Reflecting this, the West African countries that scored highest for arms trafficking are all epicentres of violence in the region.

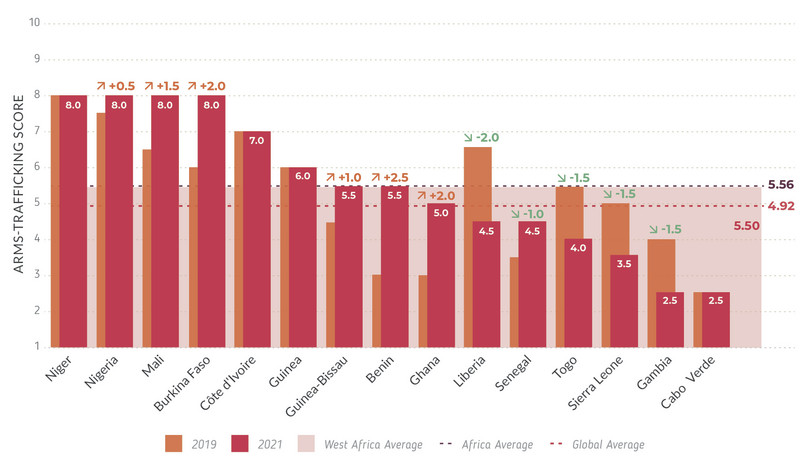

Figure 10 Arms-trafficking scores by country, West Africa.

Organised Crime Index Africa 2021

There is a pervasive arms-trafficking market across West Africa, which has an average Index score of 5.50 (above the global average score of 4.92).10 While low scores for arms trafficking in many of West Africa’s coastal states – including Gambia, Cabo Verde and Sierra Leone, for example – bring down the regional average (East Africa, Central Africa and North Africa all have average arms-trafficking scores greater than the West African average), the nevertheless elevated score is driven overwhelmingly by Nigeria and the Sahelian states of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, all of which scored 8 on the arms-trafficking indicator.

Arms trafficking both exacerbates conflict and grows as a consequence of conflict, rising insecurity and the increase in the number of armed actors involved. In Mali, since 2016, as armed groups (including jihadist groups, armed militias and other non-state and state actors) have proliferated throughout the country, the arms-trafficking market has expanded markedly.11 This is reflected in the Index rankings, with Mali scoring 6.5 for arms trafficking in 2019 and 8 in 2021. Weapons stock circulating throughout the country is replenished by new materials looted from military supplies, leaked by corrupt elements of the Malian armed forces or smuggled into the country. The influx of a number of new weapons from Libya in 2021, tracked in the northern town of Ber (which operates as an important hub in the trade), put paid to the growing theory that new weapons were no longer being trafficked from Libya.12

In Nigeria, rising insecurity has also fuelled demand for arms – both by criminal and conflict actors involved in banditry, kidnapping, robbery and oil-related violence, and by communities and vigilante groups who use them for self-protection. Index scorings show a more minor increase in the arms-trafficking market in Nigeria – from 7.5 in 2019 to 8 in 2021 – than in Mali. Many weapons in circulation in Nigeria are legitimately procured but diverted into the illicit market from national stockpiles.13 Heightened demand has driven the expansion of a burgeoning local arms-manufacturing market, further swelling the stocks of weapons in circulation.14

Conflict expands some illicit markets: Human trafficking

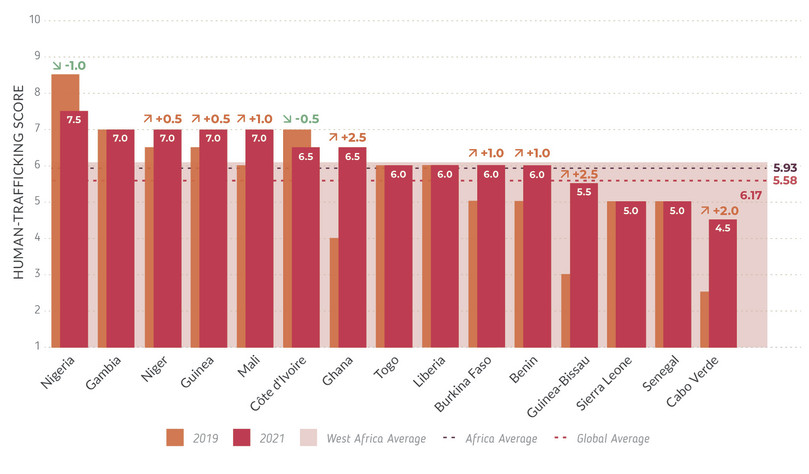

Human trafficking, the highest-scoring criminal market in West Africa (at 6.17),15 typically grows in conflict areas, as people displaced by conflict experience heightened vulnerability to exploitation in contexts that constitute trafficking, including forced labour, sexual exploitation and forced marriage.16 Human trafficking experienced an overall, albeit minor, increase across West Africa between 2019 and 2021 (+0.33), according to the Index. In Niger, which is among the highest-scoring countries for human trafficking in West Africa, the Index marked a minor increase (+0.5) between 2019 and 2021 as trafficking networks consolidated their operations regionally.

Figure 11 Human-trafficking scores by country, West Africa.

Organised Crime Index Africa 2021

Conflict zones often provide an opportunity for market expansion and diversification as transnational actors identify easier routes through conflict areas or find a rising demand for new products. In the context of human trafficking, conflict acts as an amplifier of pre-existing trafficking practices, and only to a lesser extent does it create new forms of demand for the services of trafficked persons.

The trafficking of children into combatant roles, or into service roles to conflict actors, as has occurred in relation to some armed groups operating in northern Mali, is often highlighted as a ‘new form’ of trafficking in conflict contexts.17 However, the recruitment of children into combatant roles typically builds on practices that preceded conflict. For instance, in the Central African Republic (CAR) – which is estimated to have one of the highest levels of human trafficking globally (the market ranked 7 in 2019 and 7.5 in 2021, according to the Index) – all armed groups use children in their ranks. However, long before the outbreak of the civil war in 2012, several thousand children were present not only in rebel groups but in the CAR state army. The intensification of the conflict triggered armed groups to massively escalate the recruitment of children; however, this was a pre-existing practice perpetrated not only by armed groups but by the state, which built on long-standing practices of child labour in non-combatant contexts.18

Tenuous relationships between instability and illicit markets

While there are numerous different forms of organized-criminal activity with strong links, whether direct or indirect, to conflict and instability across West Africa and the wider continent, the Index demonstrates no obvious connection between some criminal markets and conflict dynamics.

Two criminal markets for which the Index shows no statistically significant relationship to the GPI are the cannabis trade and the illicit wildlife trade.19 Cannabis is cultivated across large parts of West Africa, including in countries such as Sierra Leone and Gambia which are relatively peaceful states in the African context, ranking respectively 39th and 46th continentally on the GPI.20 Likewise, the illegal wildlife trade is highly pervasive in a number of comparatively stable countries, such as Senegal and Ghana (and to a somewhat lesser extent, Togo and Liberia).21

There are clear cases where both markets have been clearly linked to the financing of armed groups or to otherwise perpetuating instability – such as between the illicit wildlife trade and armed groups in the DRC, or the cannabis markets and separatist rebels in the Casamance region of Senegal. However, when Index scores for these two markets are analyzed across West Africa, or indeed across Africa as a whole, there is no clear correlation with instability.

While the nature of the relationship between illicit markets and instability is dependent on a wide array of factors, the high degree of legitimacy typically enjoyed by both cannabis and illicit wildlife markets among local communities is likely to be one contributing element.

Conflict and resilience to organized crime

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Index results show that those African countries facing significant levels of conflict, violence or other political, security and social pressures have far lower levels of resilience to organized crime, as evidenced by the moderately strong correlations between resilience and state fragility (-0.63) and resilience and peace (+0.51).22

In conflict settings, it could be the case that state attention is diverted to war efforts, which inevitably leaves social, economic and security institutions weakened. Similarly, in conflict settings, when there is a dispute over territory or resources, territorial control and social cohesion are likely to be diminished. All of these circumstances can lead to an overall decline in resilience to organized crime. In West Africa, four of the five lowest-scoring countries for resilience (Mali, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and Niger) are all experiencing conflict or political upheaval.23 Indeed, since 2020, all four countries have experienced either coups or attempted coups. In Burkina Faso, which experienced one of the steepest decreases in resilience between 2019 and 2021, as shown in the indexes, the state lost control of swathes of territory to violent-extremist groups.24

Figure 12 Relationship between conflict and resilience to organized crime.

Organised Crime Index Africa 2021; Vision of Humanity (Institute for Economics and Peace); Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project

Conclusion

The results of the 2021 Organised Crime Index provide a new lens for analysing the relationship between criminality, violence, conflict and instability. The findings support existing research tracking the myriad ways in which criminal markets and conflict can feed into each other, but also underscore the importance of distinguishing between markets. Narratives surrounding the nexus between crime and conflict are often oversimplified, pointing to a clear linear correlation. Instead, it is important to recognize that not all illicit flows have the same relationship to conflict, and that even where the two phenomena grow in parallel, causality differs and should not be assumed. Stabilization responses, in turn, must be crafted accordingly and should prioritize addressing those illicit economies that are particularly destabilizing, such as arms trafficking.25

Notes

-

GI-TOC, Global Organized Crime Index 2021, https://ocindex.net/assets/downloads/global-ocindex-report.pdf. ↩

-

ENACT, Organised Crime Index Africa 2021: Evolution of crime in a Covid world, A comparative analysis of organized crime in Africa, 2019–2021, https://africa.ocindex.net/assets/downloads/enact_report_2021.pdf. ↩

-

‘High criminality’ is defined as a score greater than or equal to 5.5. ↩

-

The average Global Peace Index score in West Africa increased by 0.05 between 2018 and 2020, reflecting a deterioration in levels of peace. Vision of Humanity, 2020 Global Peace Index, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/#/. ↩

-

An important point to consider when analyzing how scores have changed since the 2019 Index is that the fluctuations should be approached with caution. Scores for Africa in the 2021 Index have been calibrated for global comparisons, significantly expanding the tool’s comparative scope from the 2019 iteration, which was limited to a continental analysis of 54 countries. ↩

-

ENACT, Organised Crime Index Africa 2021: Evolution of crime in a Covid world, A comparative analysis of organized crime in Africa, 2019–2021, https://africa.ocindex.net/assets/downloads/enact_report_2021.pdf. ↩

-

Summer Walker and Mariana Botero Restrepo, Illicit Economies and Armed Conflict: Ten dynamics that drive instability, GI-TOC, January 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/GMFA-Illicit-economies-28Jan-web.pdf. ↩

-

ENACT, Organised Crime Index Africa 2021: Evolution of crime in a Covid world, A comparative analysis of organized crime in Africa, 2019–2021, https://africa.ocindex.net/assets/downloads/enact_report_2021.pdf. ↩

-

Summer Walker and Mariana Botero Restrepo, Illicit Economies and Armed Conflict: Ten dynamics that drive instability, GI-TOC, January 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/GMFA-Illicit-economies-28Jan-web.pdf. ↩

-

GI-TOC, Global Organized Crime Index 2021, https://ocindex.net. ↩

-

Peter Tinti, Whose Crime is it Anyway? Organized crime and international stabilization efforts in Mali, GI-TOC, February 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Whose-crime-is-it-anyway-web.pdf. ↩

-

GI-TOC, Global Organized Crime Index: Mali, https://ocindex.net/assets/downloads/english/ocindex_profile_mali.pdf. ↩

-

GI-TOC, Global Organized Crime Index: Nigeria, https://ocindex.net/assets/downloads/english/ocindex_profile_nigeria.pdf. ↩

-

GI-TOC, The crime paradox: Illicit markets, violence and instability in Nigeria, forthcoming. ↩

-

This high regional score is not driven by a few extremely high-scoring outliers, but rather by relatively high scores across a large number of countries in the region. ↩

-

Summer Walker and Mariana Botero Restrepo, Illicit Economies and Armed Conflict: Ten dynamics that drive instability, GI-TOC, January 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/GMFA-Illicit-economies-28Jan-web.pdf. ↩

-

ENACT, Organised Crime Index Africa 2021, https://africa.ocindex.net/assets/downloads/2021/ocindex_summary_mali.pdf. ↩

-

Interviews with NGO representatives, CAR, July 2018. ↩

-

Under the Index, ‘illicit wildlife trade’ refers to both flora and fauna markets. Analyzing the global index (193 countries) reveals a positive but considerably weak correlation between fauna crimes and the GPI, and no correlation between the latter and flora crimes. Analyzing the Africa index (54 countries) reveals no correlation between fauna and flora crimes and the GPI. ↩

-

Vision of Humanity, 2021 Global Peace Index, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/#/. ↩

-

ENACT, Organised Crime Index Africa 2021, https://africa.ocindex.net. ↩

-

ENACT, Organised Crime Index Africa 2021, https://africa.ocindex.net/assets/downloads/enact_report_2021.pdf. ↩

-

Liberia, which scored the fifth lowest for resilience, is a post-conflict context where stabilization programming has had mixed effects on improving state resilience. ↩

-

ENACT, Organised Crime Index Africa 2021: Burkina Faso, https://africa.ocindex.net/assets/downloads/2021/ocindex_summary_burkina_faso.pdf. ↩

-

Peter Tinti, Whose crime is it anyway? Organized crime and international stabilization efforts in Mali, GI-TOC, February 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Whose-crime-is-it-anyway-web.pdf. ↩