Violence surges as criminal networks spread to new territories amid economic downturn in Jos, Nigeria.

The central Nigerian city of Jos and its surrounding areas have been experiencing a resurgence of violence since 2021. A spike in criminal activity in Jos, partly attributable to increases in unemployment and economic hardship,1 is one key driver behind this explosion in violence, with fatal incidents linked to illicit markets, including cattle rustling, arms and drug trafficking, and kidnapping for ransom, doubling between 2020 and 2021.2

An increase in inter-communal clashes, driven partly by the growing operations of rural based militias in peri urban areas of Jos, has further contributed to escalating violence. In the most recent episode, at least four people were killed in two separate incidents involving Christians and Muslims in February 2022.3 These incidents are part of a cycle of attacks and reprisals that have intensified over the past year.

Like the rural based militias, criminal networks have also expanded their territories of operation, and have spread throughout urban Jos. One community leader noted that ‘ten years ago we didn’t have many criminal groups in this area but today they are too many for me to count.4 During election periods, these criminal work on behalf of political actors to disrupt rallies, fuel violent protests, and intimidate or even kill opponents. For example, the Jos East local government chairperson of the Action Democratic Party was shot dead on 2 November 2017 in what was generally believed to be a politically motivated murder.5 In a more recent incident, also believed to be politically motivated, on 31 May 2021, the aid of Governor Ortom of Benue State was shot and killed in Jos.6

Jos first emerged as a hub for illicit markets, and became notorious for its rampant communal violence, between 2001 and 2018. Large-scale violent clashes between Christian and Muslim communities escalated,7 and Boko Haram terrorists targeted the city between 2010 and 2015, with a series of bombings sparking reprisals and further polarizing Christian and Muslim communities. Although violence was ameliorated through government and community responses, which contributed to a decrease in conflict- and crime-related deaths in the city between 2018 and 2020, this proved to be a temporary lull.8

Violence is likely to escalate further in the lead-up to the 2023 elections, as political actors instrumentalize criminal networks to intimidate, threaten or harm political opponents. Criminal network composition maps onto Jos’ religiously segregated social and political landscape – political instrumentalization therefore risks feeding into longstanding conflicts and escalating communal tension.

Violence and crime experience a resurgence in Jos

The spread of criminal networks to a greater number of the city’s neighbourhoods has caused a major spike in violent crime since 2021. The Emani National Crime Survey, a crime-perceptions survey commissioned by the GI-TOC in November 2021, found that respondents ranked Jos North as the local government area (LGA) with the highest levels of criminal activity in Plateau State, and fourth highest in the country.9 All of the residents of Jos North LGA who participated in the Emani survey reported that violence has increased in the city in the last five years.

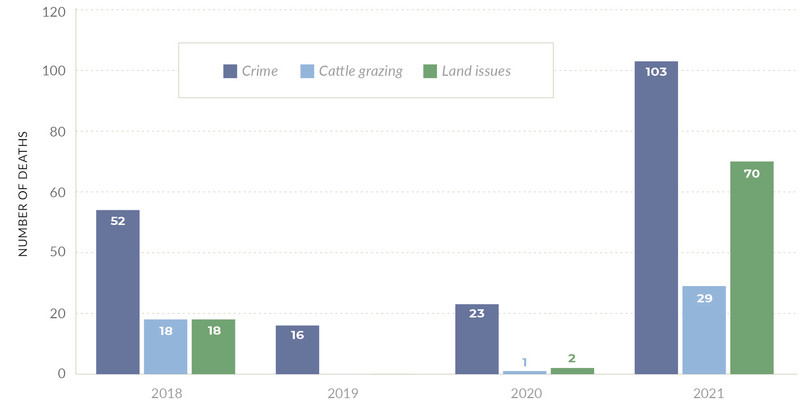

Data from Nigeria Watch, a civil-society organization that tracks violence in Nigeria, illustrates the spike in crime-related violence in Nigeria since 2020. According to Nigeria Watch, there were 68 crime-related deaths in Jos North between 2018 and 2019. The number of crime-related deaths has increased significantly, almost doubling over the last two years, with 126 deaths recorded between January 2020 and December 2021. Similarly, the number of people killed in incidents involving cattle grazing and land-related issues almost tripled between 2018 and 2021, from 36 to 99.10

Figure 5 Deaths related to crime, land issues and cattle grazing in Jos North, 2018–2021.

NOTE: ‘Crime-related deaths’ are defined as deaths that result from violence perpetrated while committing a criminal activity.

Nigeria Watch

The resurgence in violence in Jos since 2021 is due primarily to the fact that many members of the communities have resorted to joining street gangs, cult groups and armed militias that engage in myriad illicit economies from drug trafficking, arms trafficking and armed robbery to cattle rustling and kidnap for ransom.11 The increase in the prevalence and spread of criminal networks in Jos is to a large extent a result of the recent countrywide rise in poverty levels, unemployment and inflation.12 COVID-19 lockdowns, as well as the significant hit to the economy as a result of the oil price slump, were a contributing factor to Nigeria’s deepest recession in two decades in 2020.13

Urban criminal gangs spread to new territories

The sharp increase in the volume of illicit activities carried out by criminal networks, in addition to their geographic expansion, has been notably felt by members and leaders of the community in Jos, who testify to the heightened instability in the city and surrounding areas.14 One resident of Gada Biyu, a Christian suburb south-west of the city centre with a strong presence of cult groups, observed that ‘ten years ago we only used to hear about cultism from a distance, but now there are many of them living among us.’15

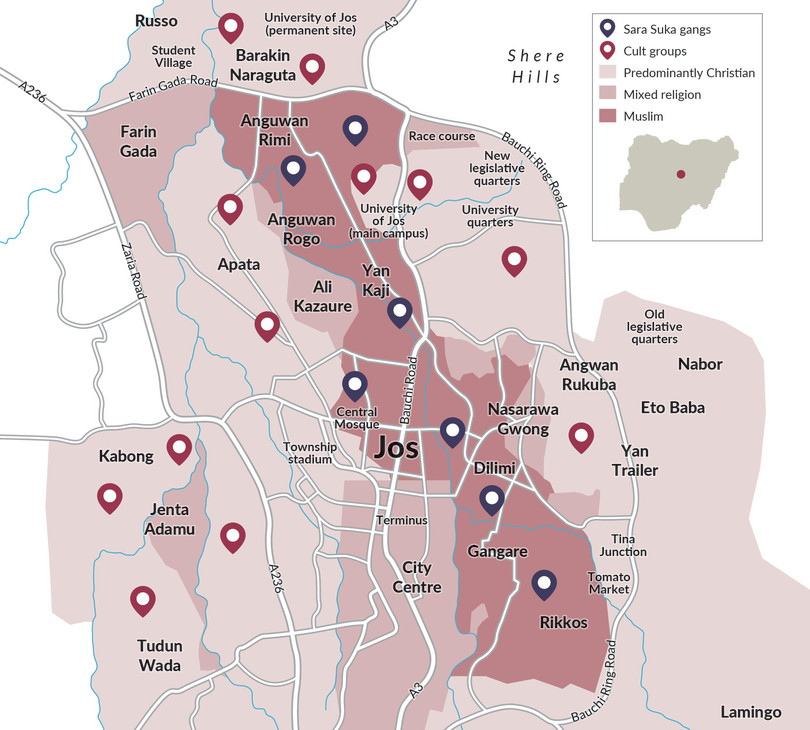

Figure 6 Religious divisions and criminal group territory in Jos.

K L Madueke, Routing ethnic violence in a divided city: walking in the footsteps of armed mobs in Jos, Nigeria. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 56(3), (2018), 443–470, supplemented by GI-TOC interviews with community leaders, vigilantes and members of criminal networks in Jos between November 2021 and February 2022, and media reports

Two criminal networks play a prominent role in recent incidents of violence in Jos: cult groups, which are found mainly in Christian neighbourhoods, and Sara Suka street gangs, which are typically embedded within predominantly Muslim communities.16 The composition of most criminal networks reflects the religious segregation of neighborhoods in Jos, and groups are typically religiously homogenous (see Figure 6).

Sara Suka gangs originated in Bauchi, a city 100 kilometres north of Jos, but gained popularity in Jos between 2011 and 2013, and have since spread to most of Jos’s predominantly Muslim neighbourhoods.17 While Sara Suka gangs are largely made up of boys and men between the ages of 13 and 25, some women are associated with the gangs; according to a vigilante leader, the women help in concealing drugs and weapons when security forces are on a gang’s trail.18 Some of them live in brothels, which Sara Suka members use as hideouts and for peddling drugs.19

In predominantly Christian neighbourhoods, on the other hand, cult groups are the dominant criminal organizations. The cult groups that operate in Jos, including Black Axe, Vikings, Aye and Buccaneers, were traditionally based on university campuses, recruiting members primarily from student populations. Over the last ten years, however, cult groups in Jos have decentralized, starting to operate beyond university campuses and spreading to the streets.20 According to a police officer, ‘many cult members are non-educated individuals who have never seen the four walls of a university classroom, and some are as young as 13.’21

While originally mainly involved in armed robbery, burglary and petty theft, since 2020, Sara Suka gangs have engaged in the trafficking of drugs (including tramadol, codeine and cannabis), which has brought them into conflict with long-established trafficking networks, occasionally resulting in violence.22 Like Sura Suka gangs, cult groups were also originally known for armed robbery and extortion rather than drug trafficking. However, over the last five years, they have been increasingly involved in the trafficking of cannabis, tramadol and codeine.

There are varying explanations given for this shift in operations. A vigilante leader explained that ‘cult groups have become involved in drug trafficking because levels of poverty have increased over the last five years, and they are not getting as much as they used to through armed robbery.’23 A former cult member has explained that cult groups now engage in drug trafficking because it has become much more lucrative than it was five years ago.24

Rural-based violence expands to peri-urban areas

The expansion of criminal networks’ operations in the city is not the only worrying trend currently being experienced in Jos, however. Conflict and crime dynamics in Jos are currently in a period of flux, with long-standing divides between the nature of urban and rural conflict in the city breaking down. Between 2010 and 2019, the violence in the rural areas involved well-coordinated attacks and massacres by heavily armed rural-based militias, while the violence in urban Jos involved sporadic clashes between armed mobs in Christian and Muslim communities. Since 2021, however, rural-based militias have expanded their attacks to Jos’ peri-urban areas. These militias are also involved in organized-criminal activities, including cattle rustling, kidnapping for ransom and arms and drug trafficking. The expansion of their operations to peri-urban areas is thus expected to have a significant impact on the dynamics of criminality in Jos.

Though urban and rural violence in Plateau State is often conflated, they are two distinct phenomena. While it is often the case that an escalation in rural conflict can cause tension in urban Jos, and vice versa, the issues, actors and level of sophistication of the attacks differ. Urban conflict predominantly takes place between Christian and Muslim communities, while conflict in the rural areas is typically between pastoralists and farming communities. Moreover, whereas violence in urban Jos typically takes the form of clashes between spontaneously mobilized mobs armed with cutlasses, machetes, sticks, Molotov cocktails and a few firearms, rural-based violence is in the form of well-coordinated attacks and massacres perpetrated by heavily armed militias.

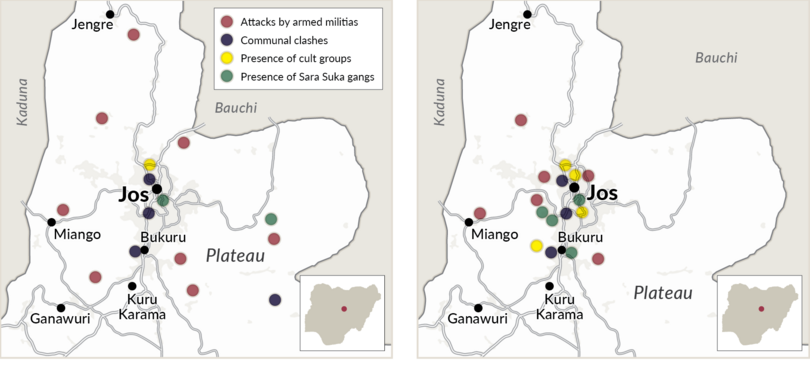

However, these dynamics have been changing since 2020, as shown in Figure 7. The well-coordinated attacks that were once restricted to the rural areas have increasingly moved to peri-urban areas, and towards the city centre. Recent incidents of violence in peri-urban areas have sparked clashes in the city centre, where urban criminal networks with religious overtones play a prominent role, suggesting an increasing blurring of the spatial boundary between the well-coordinated attacks once restricted to the rural areas and the relatively more spontaneous Christian–Muslim clashes in the city.

Figure 7 Attacks by rural-based militias and communal clashes in Jos.

GI-TOC interviews with community leaders, vigilantes and members of criminal networks in Jos between November 2021 and February 2022

The expansion of rural-based violence towards the city started just over three years ago when in September 2018, an attack by a rural militia left 11 dead in Lopandet Dwei, a peri-urban settlement at the southern border of the city.25 A similar attack three weeks later left 12 people dead in Rukuba Road.26 The deadly attacks by urban criminal networks in the Rukuba Road area on 14 August 2021, which killed 22 passengers, largely Muslim Fulanis, marked a key turning point, as it appeared to position Fulanis at the centre of the clashes for the first time. It triggered lethal reprisals by rural-based militias, who are predominantly Fulani, in Yelwa Zangam that month, as well as the killings by Fulani herdsmen in Bida Bidi and retaliatory attacks by Christian youth in February 2022. Cumulatively these have blurred the boundary between urban- and rural-based violence in Jos, all occurring within a few kilometres of the city centre.

A house that was destroyed in the attack on Yelwa Zangam community.

Photo: Nanmwa Golok

This blurring may have implications for the actors involved in violence and crime in Jos and the weapons used, particularly because urban criminal networks have also been spreading to more rural neighborhoods. The growing overlap in operational territories of rural-based militias and urban criminal networks could enable alliances to be built between the two, which would allow urban networks access to the more sophisticated weapons of rural-based militias. Moreover, as mentioned above, rural-based militias are involved in crimes that have not historically been features of urban Jos, such as cattle rustling and kidnap for ransom. Were these crimes to spread into the city centre, this would mark a further sharp escalation in violence associated with urban criminal markets.

Instrumentalization of criminal networks by political actors

To compound the issues of criminal groups and violence is the prospect of the instrumentalization of these criminal networks by political actors. Election years see upticks in political violence across Nigeria, but particularly in Jos, which was listed as one of six areas with a high potential for violence during the 2019 elections.27 Much of this election-related violence is perpetrated by criminal networks.28 The proliferation of street gangs and cult groups in Jos has already increased the level of violent crime over the past year, and this is only likely to escalate further in this upcoming election year as political actors recruit these groups to attack or intimidate their opponents.

The co-option of criminal groups by political actors has been a source of violence and instability in Jos for the past 15 years. In 2008, violent post-election protests led, according to a security expert, by ‘party loyalists who were essentially criminals and hoodlums working for politicians’ spiralled into large-scale clashes that lasted two days and resulted in 700 deaths.29 The 2015 elections were also marred by large-scale violence, in which 800 people were killed.30

The 2019 elections marked a contrast to precedent in the absence of deadly clashes. However, the atmosphere was very tense with a visible presence of members of cult groups and Sara Suka harassing residents to vote a particular candidate in several communities, including Gada Biu, Angwan Rukuba, Angwan Rogo and Nasarawa.31

In the lead-up to the 2023 elections, this intertwining of criminality and religious affiliation risks feeding intergroup violence. Moreover, the religious homogeneity of Sara Suka and cult groups, enables politicians to use religious affiliation to enlist their support and loyalty. In turn, criminal networks working for political interests use their religious affiliation to gain local legitimacy and enjoy a high degree of impunity in their illicit activities.

Conclusion

The resurgence of violence in Jos since 2021 is due in large part to a spike in criminal activity, in turn triggered by a significant economic hit suffered by the population. However, not only have the illicit operations of criminal networks in urban Jos intensified, but rural-based militias have also shifted their attacks towards peri-urban areas of the city. The case of Jos demonstrates that economic downturns have a particularly consequential impact on conflict-affected areas and can contribute to escalating crime and violence by further destabilizing livelihoods and forcing more people into illicit activities, including involvement in criminal networks. Moreover, in settings characterized by conflict-induced segregation, criminal affiliation can map onto group identities, feeding into longstanding conflicts, driving instability and blurring the boundary between criminality and conflict. In the run up to the 2021 elections, criminal networks with ethnic and religious overtones risk being instrumentalized to intimidate, threaten or harm political opponents. To be effective, responses to violence and crime ought to take into account the manner in which economic shifts, organized crime, violence and politics intertwine in conflict-affected settings.

Notes

-

In 2020, Nigeria experienced its worse economic depression in two decades. The inflation-induced increase in food prices which occurred between June 2020 and June 2021 increased the percentage of Nigerians living below the poverty line from 40.1 percent to 42.8 percent. ↩

-

Between January and December 2021, there were 215 deaths related to violence and crime: 114 of these deaths were in crime-related incidents, 30 were caused by altercations related to cattle grazing and 71 resulted from violence emanating from land disputes; see the Nigeria Watch database at http://www.nigeriawatch.org/index.php?urlaction=evtMap. ↩

-

Ado Abubakar Musa and Dickson Adama, Four travellers killed in Jos, Daily Trust, 17 February, 2022, https://dailytrust.com/4-travellers-killed-in-jos. ↩

-

GI-TOC interview with community leader, 17 December 2021. ↩

-

Adesola Ayo-Aderele, Plateau ADP chairman, Josiah Waziri Fursom, assassinated, Punch, 4 November 2017, https://punchng.com/plateau-adp-chairman-josiah-waziri-fursom-assassinated. ↩

-

Johnson Babajide, How Gunmen Killed Ortom’s Aide In Jos, Tribune, 3 June 2021, https://tribuneonlineng.com/how-gunmen-killed-ortoms-aide-in-jos. ↩

-

The city experienced clashes in 2001, 2004, 2008, 2010 and 2011. ↩

-

Over the last 10 years, both the federal government and the Plateau State government have established various security taskforces and agencies to tackle instability, including Operation Safe Haven, Operation Rainbow and the Plateau Peace-Building Agency. In addition, international NGOs and grassroots civil-society organizations have implemented various peacebuilding and reconciliation initiatives. ↩

-

GI-TOC, Emani National Crime Survey, 2021, https://datastudio.google.com/reporting/dc0ccf1d-f94d-4834-a789-b372b658e861/page/PZzTC. ↩

-

See the Nigeria Watch database at http://www.nigeriawatch.org/index.php?urlaction=evtMap. ↩

-

GI-TOC interview with journalist, 23 March 22. Phone. ↩

-

The inflation-induced increase in food prices which occurred between June 2020 and June 2021 increased the percentage of Nigerians living below the poverty line from 40.1 percent to 42.8 percent ↩

-

The COVID-19 pandemic and the crisis of lockdowns in Nigeria: The household food security perspective, APSDPR, https://apsdpr.org/index.php/apsdpr/article/view/484/800 ↩

-

GI-TOC interview with community leader in Jos, 2 February 2022. ↩

-

GI-TOC interview with resident of Gada Biu, 8 February 2022. ↩

-

Interviews with security experts and community leaders, 17–18 February 2022. ↩

-

GI-TOC interview with Angwan Rogo youth in Jos, 26 November 2021. ↩

-

Interview with vigilante leader, 6 November 2021. ↩

-

Interview with former member of Sara Suka, 18 February 2022. ↩

-

GI-TOC interview with former cultist in Jos, 14 February 2022. ↩

-

GI-TOC interview with security officer in Jos, 12 December 2021. ↩

-

These trafficking networks continue to operate in Jos, but do not feature in the escalating urban violence to the extent that the cults and Sara Suka gangs do. ↩

-

GI-TOC interview with vigilante in Jos, 6 March 2021. ↩

-

GI-TOC interview with former cultist in Jos, 14 February 2022. ↩

-

Gyang Bere, Gunmen kill 11, injure 12 persons in Plateau, The Sun, https://www.sunnewsonline.com/gunmen-kill-11-injure-12-persons-in-plateau. ↩

-

Tension In Jos As Gunmen Kill 12, Including Nine Family Members, Sahara Reporters,http://saharareporters.com/2018/09/28/tension-jos-gunmen-kill-12-including-nine-family-members ↩

-

International Crisis Group, Nigeria’s 2019 Elections: Six States to Watch, Africa Report No. 268, 21 December 2018, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/268-nigerias-2019-elections-six-states-watch. ↩

-

Hilary Matfess, Power, elitism and history: Analyzing trends in targeted killings in Nigeria, 2000 to 2017, GI-TOC, December 2018, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/analyzing-trends-in-targeted-killings-in-nigeria. ↩

-

GI-TOC Interview with security expert in Jos, 17 February 2022. ↩

-

Andrew Ajijah, Youth set ablaze PDP leader’s house, Premium Times, 29 March 2015, https://www.premiumtimesng.com/regional/north-central/179993-breaking-youth-set-ablaze-pdp-leaders-house.html. ↩

-

GI-TOC Interview with journalist, 1 March 2021, by phone. ↩