The abalone connection: Marine-mollusc smuggling continues to play a part in the South African meth industry.

It is one of the stranger quirks of crime history that a marine snail became one of the key drivers in the development of the South African synthetic drugs market from the 1990s onwards, as well as forming a lucrative illicit market in its own right. Over two decades, the illegal market for South African abalone (Haliotis midae, also known as perlemoen) has grown to the point where over 2 000 tonnes are being poached from South African waters annually, according to 2018 estimates from wildlife monitoring group TRAFFIC.1

The growth of this poached abalone market helped fuel the rise in trafficking of synthetic drugs and their precursors to South Africa. Although much has changed since the 1990s, according to interviews with abalone poachers and middlemen, many of the same dynamics that established the abalone–synthetics connection still remain in place today.

The emergence of abalone poaching and the politics of fishing quotas

Large-scale abalone poaching is a relatively recent phenomenon in South Africa. Quotas restricting the maximum catch of species, including abalone, were introduced in South Africa in the late 1960s, but poaching remained at low levels for decades.2

This began to change during South Africa’s democratic transition in the early 1990s.3 In an effort to transform the coastal fishing industry, the new post-apartheid government tried to create a more equitable licensing and catch quota scheme. As a result, enforcement efforts against poaching were significantly expanded, penalties were increased and special environmental courts were established to prosecute offenders.4

Abalone is prepared for cooking at Hangberg, a poaching hotspot on the Western Cape coast.

Photo: Shaun Swingler

The new policies had unintended consequences, favouring newcomer commercial fishing operators and further marginalizing local operators who had relied of small-scale fishing for their livelihoods.5 As a result, poaching increased.

The changes also delegitimized the efforts of state authorities in the eyes of coastal Cape communities.6 Illicit catches of abalone and crayfish grew as fishers undertook to operate outside the confines of a system that they saw as being both corrupt and prejudiced.7

Access to marine resources (including abalone) as dictated by the fishing quotas remains a deeply political issue today. Those who poach and transport abalone often point to the limitations on the legal market as the reason they feel forced into the illegal trade.

‘The quotas forced people to go and dive for perlemoen and it’s unfair, because it makes an honest man trying to provide for his family into a criminal who is now smokkeling [illegally trafficking] with perlemoen’, said Junaid, a 53-year-old transporter of abalone in the Cape Agulhas area in the Western Cape, who is also a former diver for abalone.8 (Names of interviewees have been changed).

Granwil, a fisherman and gang member in Hawston, on the Western Cape coast, agreed. ‘The government is forcing the fishermen and the communities into illegal trade … they sell our shores to China and to other fishing countries and as a result they reduced our quotas … obviously then, we are forced to mine for abalone illegally at night or any time.’9

A diver returns to the surface with a haul of poached abalone, and the shucking tool used to prise the abalone from their shells.

Photo: Shaun Swingler

The development of the meth-abalone connection

In the space of a few years in the 1990s, the poaching of abalone became a lucrative, organized criminal enterprise, with Cape gangs moving in to dominate what had become a multi-million-dollar illicit trade.10 Gang control of the trade continues today. Ernie ‘Lastig’ Solomon, the late leader of the Terrible Josters street gang, was a prominent figure in the Western Cape abalone trade in recent years, monopolizing the abalone trade along a large swathe of coastline until his assassination in November 2020.11 This has reportedly left a power vacuum in the market and led to competition between different underworld figures for Solomon’s position.

Darryl, an abalone smuggler in Hawston, which was Solomon’s territory, said ‘Ernie Lastig played a big part in the fishing industry, because he regulated it in a way that the government didn’t’. Darryl viewed Solomon’s thuggery almost as a necessary evil. ‘Ernie Lastig was like a warm beer, in that it doesn’t taste that good, but at least it’s still a beer … Ernie taxed us on perlemoen and crayfish, but he also protected the community from other unscrupulous gangsters that would have caused a lot of havoc here for us.’12

Chinese syndicates, which had been embedded in the country since at least the early 1970s, became the dominant buyers for illegally harvested abalone from Cape gangs.13 The abalone, so easily harvested and acquired by the Cape gangs, was a high-priced Asian delicacy that could be smuggled out along existing routes in neighbouring countries and sold by the Chinese syndicates at a significant profit in Hong Kong.14

Today, meth is the most commonly used drug in the Eastern and Western Cape provinces in South Africa

Photo: Shaun Swingler

A sample of crystal meth on sale in Cape Town. This is the type of meth known in South Africa as ‘Pakistani meth’, imported from Afghanistan via Pakistan.

A barter economy arose between the gangs and their Chinese buyers, eliminating the need for exchanges of large amounts of cash. Chinese syndicates traded the precursor chemicals necessary to produce methaqualone in return for abalone from the Cape gangs. Commonly known as ‘Mandrax’ in South Africa, or Quaalude or ‘ludes’ in North America and Europe, methaqualone has a long history of use in South Africa. Subsequently, the Chinese networks also bartered with precursors for crystal methamphetamine, which is commonly known as ‘tik’. These chemicals – difficult and expensive to obtain in South Africa – were unregulated in China, and easily and cheaply obtained by the Chinese gangs.

It was a mutually beneficial arrangement that contributed both to the expansion of methaqualone in – South Africa as well as the introduction of domestic methamphetamine production, which was first documented in South Africa in the late 1990s.15 Domestic production and use quickly expanded alongside the growth in the illicit trade in abalone and precursors between South African gangs and Chinese organized criminal groups.16 In March 1998, a Chinese shipment containing 20 tons of ephedrine (a meth precursor) bound for South Africa was seized by Chinese law enforcement authorities.17 In the previous year the total amount of ephedrine seized globally was only 8 tonnes. This seizure was significant – 20 tons of ephedrine could have produced a staggering 13 tons of methamphetamine – and showed that industrial production of South African meth had begun.

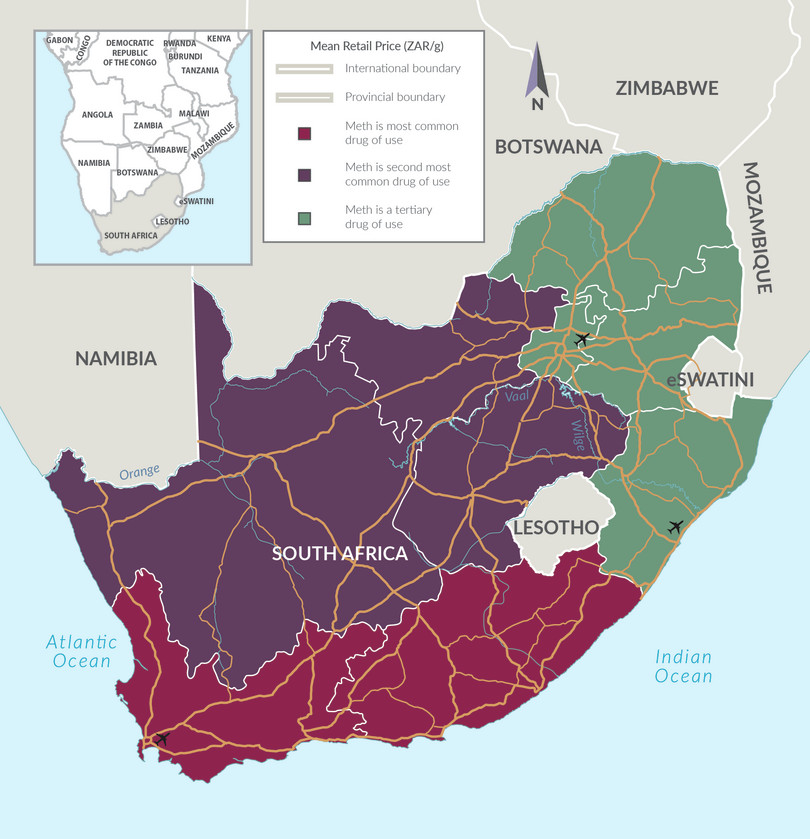

By 2005, meth had become the primary substance of use among all people who use drugs in the Western Cape province, surpassing methaqualone, cannabis and even alcohol.18 Today meth is the primary substance of use in the Western and Eastern Cape provinces, the secondary substance of use in the Northern Cape, North West and Free State provinces, and the third most commonly used substance in the rest of the country.19

Evolution of the methamphetamine and abalone trades in South Africa

Source: Jason Eligh, A Synthetic Age: The Evolution of Methamphetamine Markets in Eastern and Southern Africa, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, March 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/meth-africa/.

Figure 3 Dominance of methamphetamine use in South Africa by province, 2019.

Source: Data derived from SACENDU regional reports for July to December 2018 and 2019. Most recent figure available was used for each province.

The meth and abalone market today

The South African methamphetamine market of today is very different to its early years. Domestic production now appears to be in decline, and much is sourced from Nigerian syndicates producing methamphetamines in Nigeria, with assistance from Mexican cartels.20 As we have covered in previous issues of this Bulletin, a new supply chain has also now emerged transporting Afghan-produced methamphetamine via routes used for many years to traffic heroin to East and southern Africa. 21 However, the barter system whereby abalone are traded for drugs or their precursors still persists. Several poachers and smugglers interviewed confirmed the trade is ongoing. Junaid, the abalone transporter, put it this way: ‘They [the Chinese networks] have the gold that the gangsters want and that gold is drugs … in that type of exchange, it’s onetrading gold for another’s gold, perlemoen is gold to Chinese and drugs is gold to gangsters who have drying facilities.’22

Other abalone smugglers said that today the Chinese do not only offer drugs and precursors in this barter system. Darryl, the abalone smuggler in Hawston, said property can become part of the deal. ‘I know of a couple times that rich Chinese customers would buy a house and put it in your name just so they can get abalone from you for five years without any trouble’ he said.23

Denver, a 56-year-old boss in the Terrible Josters gang, agreed that properties sometimes formed part of abalone deals with Chinese groups. He also claimed that abalone is sometimes exchanged for the service of hitmen in the Chinese groups’ employ. However, it was not possible to verify this claim from other sources.24

Police raid an abalone-drying facility in Soshanguve, north of Pretoria, on 20 January 2018.

Photo: Julian Rademeyer

Samantha, a 60-year-old drug dealer and abalone smuggler, described how Chinese buyers can become involved at different stages of the abalone trade. Some approached the divers to source abalone directly in exchange for tik and precursors (which the divers in turn sell to gangs) and set up their own facilities to dry the abalone before exporting. Others, she said, source abalone from gang-controlled drying facilities.25

All poachers and smugglers interviewed agreed that the wheels of the trade are greased by widespread corruption. Franklin, a senior member of the 28s gang, said that ‘we must pay a lot of people so that the shipment reaches its destination and that will include wildlife people, obviously police and sometimes politicians as well that can clear the way for our shipment to get where it’s going … corruption works good here in the Western Cape.’26

The South African meth market has gone through many changes since the 1990s: new international streams of supply have emerged, use has become widespread across the country and domestic meth production has declined. Despite these changes, the illicit markets in abalone and meth have continued their unlikely symbiotic relationship.

This article draws on research from ‘A Synthetic Age: The Evolution of Methamphetamine Markets in Eastern and Southern Africa’, a new report by Jason Eligh for the GI-TOC’s East and Southern Africa Observatory. The report presents groundbreaking new research into the extent of the regional meth market. Available at: https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/meth-africa/.

Notes

-

Nicola Okes, Markus Bürgener, Sade Moneron and Julian Rademeyer, Empty Shells: An assessment of abalone poaching and trade from southern Africa, TRAFFIC, 18 September 2018, https://www.traffic.org/publications/reports/empty-shells/. ↩

-

Jonny Steinberg, The illicit abalone trade in South Africa, Institute for Security Studies, ISS paper 105, April 2005, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/99200/105.pdf; Kimon de Greef and Serge Raemaekers, South Africa’s illicit abalone trade: An updated overview and knowledge gap analysis, TRAFFIC, 2014, https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/8469/south-africas-illicit-abalone.pdf. ↩

-

Jonny Steinberg, The illicit abalone trade in South Africa, Institute for Security Studies, ISS paper 105, April 2005, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/99200/105.pdf. ↩

-

Jonny Steinberg, The illicit abalone trade in South Africa, Institute for Security Studies, ISS paper 105, April 2005, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/99200/105.pdf. ↩

-

Anthony Minnaar, Leandri van Schalkwyk and Sarika Kader, The difficulties in policing and combatting of a maritime crime: the case of abalone poaching along South Africa’s coastline, Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 14, 1 (2018), 71–87, p 80. ↩

-

Kimon de Greef and Serge Raemaekers, South Africa’s illicit abalone trade: An updated overview and knowledge gap analysis, TRAFFIC, 2014, https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/8469/south-africas-illicit-abalone.pdf. ↩

-

See the discussion of the struggle around traditional fishing rights and the impact on Cape communities as outlined in Annette Hübschle and Kimon de Greef, An exploration of the socioeconomic impacts of two drug markets in South Africa, USAID technical report, Management Systems International, 9 May 2016, pp 29–31, and Jonny Steinberg, The illicit abalone trade in South Africa, Institute for Security Studies, ISS paper 105, April 2005, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/99200/105.pdf. ↩

-

Interview, Cape Agulhas, March 2021. Note that the names of interviewees have been changed. ↩

-

Interview, Hawston, March 2021. ↩

-

Khalil Goga, The illegal abalone trade in the Western Cape, ISS paper 261, August 2014. ↩

-

Civil Society Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa, Risk Bulletin 14, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, December 2020– January 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/GI-TOC-RB14.pdf. ↩

-

Interview, Hawston, March 2021. ↩

-

Anthony Minnaar, Leandri van Schalkwyk and Sarika Kader, The difficulties in policing and combatting of a maritime crime: the case of abalone poaching along South Africa’s coastline, Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 14, 1 (2018), 71–87, p 80. ↩

-

Anthony Minnaar, Leandri van Schalkwyk and Sarika Kader, The difficulties in policing and combatting of a maritime crime: The case of abalone poaching along South Africa’s coastline, Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 14, 1 (2018), 171–87; Jonny Steinberg, The illicit abalone trade in South Africa, Institute for Security Studies, ISS paper 105, April 2005. ↩

-

Methamphetamine use is thought to have emerged in the Western Cape in volume in 1997. The first meth laboratory was seized in South Africa in 1998, barely a year after the use of meth was first detected in Cape Town. United Nations, South Africa country profile on drugs and crime, Part 1: Drugs, United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention (UNODCCP), Pretoria, 1999. ↩

-

Siphokazi Dada et al., Monitoring alcohol, tobacco and other drug use trends in South Africa (July 1996– December 2018), SACENDU Research Brief, 22, 2019; Mark Schoofs, As meth trade goes global, South Africa becomes a hub, Wall Street Journal, 21 May 2007, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB117969636007508872. ↩

-

United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention (UNODCCP), South Africa: country profile on drugs and crime: Part 1: Drugs, 1999, p 15, https://www.unodc.org/documents/southafrica/sa_drug.pdf. ↩

-

SACENDU (South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use) reports indicate that meth surpassed alcohol as the primary substance of use in the Western Cape in the second half of 2005. Siphokazi Dada et al., Monitoring alcohol, tobacco and other drug use trends in South Africa (July 1996–December 2018), SACENDU Research Brief, 22, 2019. ↩

-

Reporting from the South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU). ↩

-

Jason Eligh, A Synthetic Age: The Evolution of Methamphetamine Markets in Eastern and Southern Africa, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, March 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/meth-africa/. ↩

-

Civil Society Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa, Risk Bulletin 14, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, December 2020–January 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/GI-TOC-RB14.pdf; Civil Society Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa, Risk Bulletin 8, May–June 2020, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/esaobs-risk-bulletin-8/. ↩

-

Interview, Cape Agulhas, March 2021. ↩

-

Interview, Hawston, March 2021. ↩

-

Interview, Western Cape, March 2021. ↩

-

Interview, Western Cape, March 2021. ↩

-

Interview, Western Cape, March 2021. ↩