The evolution of the illicit economy in northern Mozambique.

The conflict in Cabo Delgado, northern Mozambique, has changed dramatically in the past year. The sophistication and scale of attacks staged by the insurgent group known as Ahlu-Sunna Wa-Jama’a (ASWJ), which has been staging attacks in Cabo Delgado since late 2017, have increased significantly. The attack on the coastal town of Palma that began on 24 March 2021, in which dozens are reported to have been killed, is another sign that the insurgency is maintaining its momentum.1

The ongoing fighting has had a knock-on effect on the illicit trafficking routes that have long been deeply entrenched in Cabo Delgado, but not in the ways that many observers expected.

Atrocities and a bloody escalation

UN refugee agencies have warned that the number of people displaced by the conflict in Mozambique is expected to reach 1 million by June 2021: currently almost 700 000 are displaced, a tenfold rise in the past year.2 Data from the Armed Conflict and Location Data Project estimates that 2 600 people have been killed in the conflict between October 2017 and March 2021.3

Horrific human rights abuses, from kidnappings and sexual abuse to mass beheadings of civilians,4 including children,5 have been documented. Human rights organizations have accused all sides of the conflict of committing war crimes, including the Mozambican military and the Dyck Advisory Group (DAG), a private military contractor employed by the Mozambican government to provide an aerial response to the insurgency.6 DAG has disputed the claims.7 The Mozambican government has also been widely criticized for blocking media and humanitarian access to the conflict.8

There was a sharp rise in the number of insurgent attacks until the rainy season started in late 2020, together with a shift in tactics adopted by the insurgents.9 ASWJ moved from conducting guerrilla raids on towns and villages – which included looting for supplies and money as well as terrorizing residents – to attacking ever-larger targets and taking control of the town of Mocímboa da Praia in late August.10

The security forces have allegedly been attempting to regain control of Mocímboa da Praia and drive the insurgents from key transportation routes. Helicopters operated by DAG with support from the Mozambican government have been deployed offshore from Mocímboa da Praia in order to cut off supply vessels reaching the insurgents by sea. As a result, local boat traffic along the northern Mozambique coast has fallen sharply.

However, with only four helicopter gunships based at Pemba (the capital of Cabo Delgado province) and a large active conflict area, this blockade has been intermittent. Supplies and new recruits are understood to be reaching the insurgents in Mocímboa de Praia from Mtwara in southern Tanzania by dhows travelling mostly at night to avoid detection and possible helicopter fire.11 According to a local source, there are rumours that a temporary logistics staging base for this supply route has been established among the islands of the Rovuma estuary.12 Small amounts of supplies are also reportedly smuggled overland, both from southern Tanzania and across the front lines in northern Mozambique itself.13 The front lines have been described as very porous.14 However, the fighters were reportedly experiencing food shortages.15

Residents of Palma are evacuated following an insurgent attack in late March 2021 that claimed dozens of lives and has left many unaccounted for. Thousands of people were rescued from the area by vessels, in what some described as a mini-Dunkirk, including ferries such as this one.

Photo: Twitter

A Dyck Advisory Group (DAG) helicopter conducts a rescue operation for people fleeing the insurgent attack on Palma. DAG is a private military company contracted by the Mozambican government to combat the insurgents, particularly through the use of helicopters.

Photo: DAG

Reports of renewed fighting have emerged in recent weeks.16 Insurgents began an assault on the coastal town of Palma on 24 March 2021, just hours after oil and gas giant Total announced that it considered the security situation to have improved enough to resume work on its gas plant on the Afungi Peninsula, very close to Palma.17 Dozens are estimated to have been killed in the fighting and thousands of residents have been forced to flee into neighbouring districts.18

Local residents and foreign gas workers were also evacuated from Palma by DAG helicopters and a collection of volunteer vessels including ferries to the port of Pemba to the south.19 The attack on Palma – which has been claimed by Islamic State (as have previous attacks by ASWJ) – has been seen as another major escalation in the conflict. At the time of writing, Mozambican security forces have announced that they regained control of Palma town after several days of insurgent occupation. Media reports have shown the widespread damage caused to the town.20

The growing scale of the conflict has brought with it international pressure on the Mozambican government to accept military support.21 On 10 March 2021, the US government designated ASWJ as a ‘foreign terrorist organization’, describing it as an affiliate of Islamic State.22 US special forces have also begun a training programme for the Mozambican military. Portugal is also finalizing a bilateral agreement with Mozambique to provide military training,23 and French naval forces are patrolling the Mozambican Channel.24

Predictions vs. Reality

These developments in the conflict have had impacts across the region, including a knock-on effect on the various trafficking routes – for heroin, rubies, gold, timber, wildlife – and migrant-smuggling routes – which have been entrenched in Cabo Delgado for decades. However, this has not taken the form that many analysts, including the GI-TOC, expected.

When the conflict first broke out in 2017 and in its early stages, many observers issued warnings about the potential for the insurgents to capitalize on trafficking routes.25 A year ago, in a previous issue of this Bulletin, we published analysis that the insurgents’ strategy may have been aimed at taking control of trafficking routes and transport hubs so as to make money from the illicit economy.

Our research at the time found that the insurgents’ links to organized crime were largely ad hoc, and trafficking routes did not form a major part of the funding streams for the organization. The links between criminal markets and insurgency at the time were more reflective of the fact that illicit economies made up a large part of economic activity in Cabo Delgado.

For example, we found that there were possible overlaps between the insurgents and drug-trafficking networks (using the same dhows for local transport, and operating in the same vicinities), and that there were opportunities for them to capitalize on other commodities such as the smuggling of rubies and gold.26 The insurgents reportedly recruited from the gemstone and gold artisanal-mining communities in Cabo Delgado and Niassa provinces at the outset of the conflict.27

The fact that the profits from both licit and illicit markets in Cabo Delgado were being channeled to a narrow political and military elite left people in the region impoverished and angry and contributed to the growing insurgency.28 For example, some early recruits into the organization were reported to be drawn from the communities of artisanal miners operating in Montepuez.29 Initial recruits from this area were attracted by ASWJ’s rhetoric of rejecting a predatory government that they felt was excluding them from mineral resources on their land.30

However, our assessment in 2020 also warned that insurgent control of trafficking routes was a risk: ‘If territorial control were achieved – along the coast from Quissanga to Palma as well as on the key inland transport corridor along the N380 road and the town of Macomia – this could vastly change the dynamics of the insurgency. Control over key sea and land routes would allow the insurgents to “tax” licit and illicit economies in the region more systematically. While there may already be some protection of heroin trafficking and involvement in the gold and ruby trade, this could expand to include human smuggling, timber trafficking and possibly a share of the illegal wildlife trade. The locations of recent attacks – which include coastal landing sites, transport hubs and the sites of natural resources – suggest that the insurgents may be targeting the illicit economy as a more substantial source of future revenue.’31

Contrary to these perceptions and predictions, our research in northern Mozambique in January and February 2021 has found that there is little evidence to suggest that illicit economies have in fact become a major source of income for the insurgents. In fact, the insurgent-controlled area and the highly militarized surrounding region have become extremely logistically difficult for trafficking networks to move contraband through. Damage to road infrastructure,32 the risks of the violence and the presence of government forces have meant that trafficking routes in the region have dramatically changed from those mapped a year ago.

However, perceptions that the insurgents are profiting from trafficking still persist. On 11 March this year, John Godfrey, a US counterterrorism envoy, referred to ‘a nexus between terrorism finance and narcotics trafficking in Mozambique that’s particularly problematic’ in relation to the US designation of ASWJ as a foreign terrorist organization.33

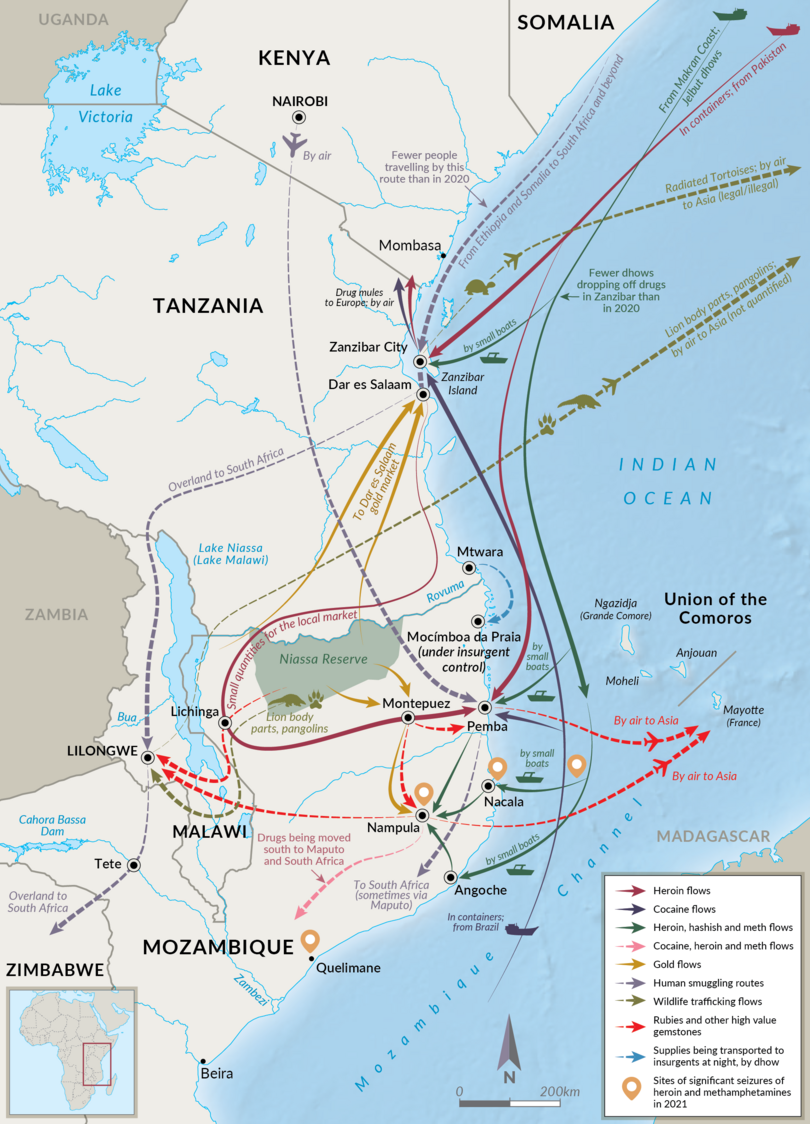

Figure 1 Illicit flows through northern Mozambique as of February 2021.

NOTE: In comparison to our research findings from 2020, several key illicit flows have shifted so as to avoid the area of insurgent activity in Cabo Delgado. Several illicit flows marked on the 2020 map below – such as flows of drugs to Comoros and Mayotte, and some goods flows out of Zanzibar – are not marked on the 2021 map above. This is not to suggest that such flows are not ongoing, but that our latest research did not confirm their continued viability.

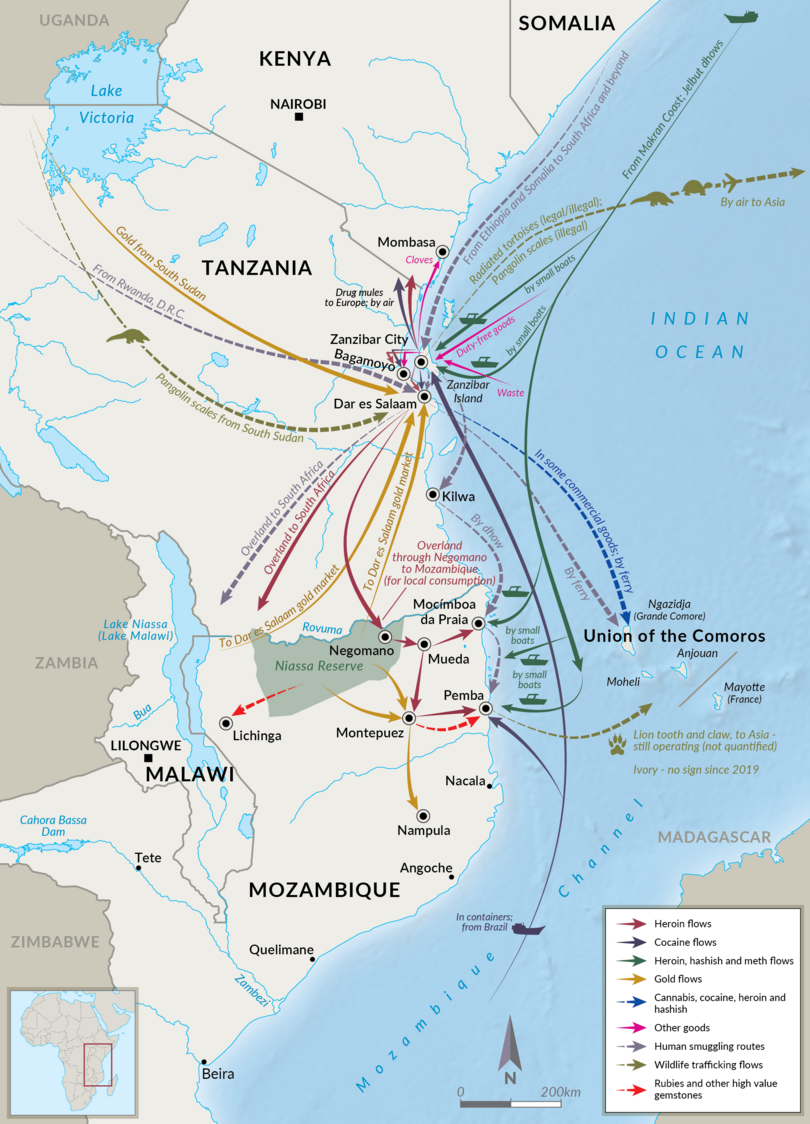

Figure 2 Illicit flows through northern Mozambique as of June 2020.

Source: Alastair Nelson, A triangle of vulnerability: changing patterns of illicit trafficking off the Swahili coast, GI-TOC, June 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/triangle-vulnerability-swahili-coast/.

The evolution of criminal economies

Although the group may not have taken control of trafficking routes, ASWJ has still had a large impact on trafficking through Cabo Delgado. The impact has been larger than that caused by travel restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had a significant impact on trafficking routes around East and southern Africa and globally.34

Drugs

Drug shipments into Cabo Delgado take place via three main methods. The best known is the trafficking of heroin and methamphetamine via dhows travelling from the Makran coast of Pakistan and Iran. Multiple law enforcement sources confirmed that dhows continued to travel to Mozambique during the pandemic.35

From a dhow that can carry up to a tonne of heroin and meth, smaller shipments are offloaded onto smaller fishing boats to be brought into harbours and beaches. A system of numbers written on each shipment corresponding to the drop-off point reportedly helps the trafficking networks deliver each shipment to the right recipients.36

In previous years, these drugs shipments were primarily heroin. Methamphetamine is a newer addition to this trafficking route, and has been detected since the beginning of 2020.37 The incidence of methamphetamine on this route has increased to such an extent that more than 50% of these shipments are now made up of meth. As we have covered in previous issues of this Bulletin, a rise in meth production in Afghanistan has led to meth being trafficked alongside heroin to southern Africa. Law enforcement sources in Mozambique reported that laboratory analysis done on meth seized in Mozambique confirmed that this was meth produced in Afghanistan.38

A small fishing dhow on the shore of Pemba, Cabo Delgado, Mozambique, reportedly one of the local vessels used to land drugs shipments.

Photo: Supplied.

Drug shipments from dhows were previously offloaded onto beaches around Mocímboa da Praia, Quissanga and Pemba in Cabo Delgado. However, drop-offs are now made at points further south, including Pemba, but also Nacala and Angoche.39 After extensive field research in early 2021, including interviews with law enforcement officers, local sources connected to the drugs trafficking routes, local drug couriers and local journalists, no evidence was found linking the ASWJ with the dhow-based drugs supply route. It appears that safety concerns over landing along the insurgent- held coastline, as well as the potential increased costs of having to move goods south through two front lines, have meant that these drugs trafficking networks have moved to the relatively safer coast of Nampula district (Nacala and Angoche).40

Large drugs seizures, made up of heroin and methamphetamines, made in Mozambique in 2021 support the conclusion that trafficking networks have moved further south.

- On 24 March, 356 kilograms of crystal meth and heroin were seized by police on Numa beach in Nacala while being offloaded from a boat. The crew escaped arrest via sea.41

- On 19 March, the Serviço Nacional de Investigação Criminal announced that they had seized 440 kilograms of heroin in Quelimane, a town on Mozambique’s central coast.42 A well-connected local source has confirmed that this seizure was made up of heroin, cocaine and cannabis.43

- On 7 March, 95 kilograms of heroin and methamphetamines were seized in Murrupula, Nampula Province, at a checkpoint on the main road south to Maputo, hidden inside a trailer.44

- In February, 6 kilograms of drugs were seized at the port of Nacala (shortly after these disappeared from the authorities’ safe keeping).45

- On 23 January, 61 kilograms of heroin and 5 kilograms of methamphetamine were seized in Nacala. According to the person arrested with the drugs, they were due to be transported to South Africa by road.46

- On 24 January, a French navy frigate seized 417 kilograms of methamphetamines and 27 kilograms of heroin from a dhow in the Mozambican Channel.47

Heroin seized in Nacala, Mozambique, in January 2021. The packaging has also been seen on other drugs shipped into Mozambique and Zanzibar. A Mozambican national was arrested in connection with the drugs.

Photo: SERNIC

One heroin trafficker known to the GI-TOC who had previously been based in Mocímboa da Praia had since moved south to Nacala, suggesting that their trafficking operation had also shifted.48

Conversely, the ASWJ insurgency has seen drug networks move out of Zanzibar into northern Mozambique. Interviews with former and current drugs mules based in Zanzibar suggested that delivery of heroin by dhows into Zanzibar has slowed, due to increased military surveillance off the Tanzanian coast due to the insurgency.49 There has also been active recruitment among the youth of Zanzibar, and some young people are known to have travelled to Mtwara to join ASWJ.50 This may have increased general security surveillance on Zanzibar, negatively impacting the smaller drugs trafficking networks.

With the increased security surveillance in and around Zanzibar, some lower-level ‘entrepreneurial’ networks appear to have shifted operations out of Zanzibar to northern Mozambique, from where they are trafficking the drugs to South Africa, and possibly back up to Zanzibar for mules to carry to Europe via air.51

Several suspects arrested in Pemba in January 2021 in connection with drugs trafficking, likely in connection with the same dhow seized by the French navy, are known to be Zanzibari.52 The suspects named a Zanzibari woman as the trafficker they were working for. This woman had previously worked as a drugs mule trafficking heroin, built up capital and now directs her own trafficking operation moving drugs from the coastal landing sites to South Africa.

The second means of trafficking drugs into northern Mozambique is inside containers that arrive on cargo ships from Pakistan carrying heroin or from Brazil carrying cocaine into the container port in Pemba. This route appears to have been unaffected by both the insurgency (as insurgent control has not stretched as far south as Pemba) and the pandemic.53 It is understood that the networks in control of heroin trafficking via container differ from those involved in the dhow trade, with these high-volume traffickers reputedly enjoying support from senior party and government officials.54 While these networks used to receive heroin via dhows from the Makran coast, they have now transferred to the more controlled and secure system of trafficking via containers.55

Third, heroin destined for local consumption is imported to Mozambique overland from Tanzania. In 2020 we reported how heroin was packaged into trucks in Dar es Salaam inside foodstuffs for export to shops in northern Mozambique, then being trucked across the Mozambique border at the Unity Bridge, in the far north-west of Cabo Delgado province.56 Now, however, the route has shifted much further west, crossing into the north-west of Niassa Province, then heading south to Lichinga and along the poor road linking Niassa and Cabo Delgado provinces. This avoids the conflict zone and still allows for heroin to be delivered to users in towns such as Montepuez and Pemba.57

Human smuggling

For years, the Swahili coast has been part of a human- smuggling route for migrants moving from the Horn of Africa to South Africa. People moving from Ethiopia and Somalia travelled south to Zanzibar, from where many would take a coastal route via dhow, which would make landing at Mocímboa da Praia and on the beaches near Pemba, typically on moonlit nights. These same dhows have also been used to transport other illicit products, including ivory and heroin, and very likely were also used by the spreaders of extremist ideologies from the Kenyan coast.58

However, this coastal movement of people has ceased, due to a combination of the insurgency, increased surveillance of the coasts and COVID-19. Thanks to COVID-19 restrictions, fewer migrants have arrived to Zanzibar in the past year, and arrivals by sea have remained low.

Instead, the passage of Ethiopian migrants via Malawi and then into Mozambique’s southern Tete province has increased. The horrific deaths of 64 migrants found dead in a cargo truck in Tete province in March 2020 turned the spotlight onto this emerging smuggling route.59 Reports of the arrest of smuggling facilitators in the region further suggests that this is an established route for movement of migrants and not an ad hoc crossing point.

As investigations in the Mozambican media have also reported, migrants are also smuggled by air from Nairobi into Pemba airport.60 Initial GI-TOC investigations into this route have found this to be a sophisticated arrangement whereby migrants are boarded in Nairobi using tickets that are issued to them only once the number of free seats on the flight is known, and without being registered on Mozambique Airlines’s (LAM) booking system. On arrival in Pemba, the migrants are held on the plane until after the crew has disembarked, whereupon all of their passports are taken to a ‘trusted’ immigration official by a facilitator. The migrants are then accommodated in houses of known smuggling facilitators in Pemba until they begin their onward journeys – some by air to Maputo and then overland to South Africa, and some overland all the way from Pemba. Our research suggested that this is a long-standing smuggling route that has only recently come to light.61

Gems

There are two major regions for sourcing gemstones in northern Mozambique. First among these are the mining sites near Montepuez in Cabo Delgado. Our research looked for evidence directly linking gemstone trafficking from the illicit mining operations with ASWJ, but no direct relationship was found. However, we heard from multiple sources that some artisanal miners sympathetic to ASWJ, or just to family members who had joined, may be supporting ASWJ financially, although none of our interviews directly confirmed this link. Thus, there is little evidence to suggest a systemic link of either gems or large-scale financial support flowing to the insurgents.

The second major area for gemstone mining is from the Msawise site within Niassa Special Reserve. Currently, our research suggests that gemstones mined in this region are primarily smuggled to Malawi, where traders are able to obtain official paperwork claiming the gems to be Malawian-mined, before being exported to Asia. Reports also suggest that this gem smuggling route is connected to the illicit wildlife trade, primarily in carnivore body parts such as lion teeth and claws, and also live pangolins from Niassa Reserve. We found no evidence of ivory trafficking in northern Mozambique, either out of Pemba or into Malawi.

The role of the insurgency

Contrary to expectation, it seems that ASWJ does not currently play a major role in any illicit flows through northern Mozambique. Instead, their presence has reshaped the criminal landscape of Cabo Delgado and caused trafficking routes to reconfigure.

This is not to definitively say that the insurgents are not benefiting from the criminal economy. It is possible, for example, that they may be benefiting from small amounts of artisanal gold mining that occur within the no man’s land south-west of Mocímboa da Praia. While helicopter and naval surveillance along the coast precludes the trafficking of bulky goods such as timber, small amounts of gold smuggled to the gold market in Dar es Salaam could provide a form of income. However, it is not currently possible to say definitively whether the insurgents are involved in this low-level gold trade.

What seems more certain is that the Palma attack has benefited the insurgents financially. They reportedly targeted banks and humanitarian supplies, which suggests that this is the current mechanism they are using to fund and supply themselves. The date of the Palma attack – just before many workers would be due to receive monthly salaries – further suggests that the insurgents’ strategy was aimed at financial gain.

Much remains unknown, and the dynamics of the conflict remain highly volatile, as the recent fierce fighting around Palma has shown. As countless other conflicts have shown in the past, armed groups can quickly adapt to engage in criminal activity and play a role in trafficking routes. As such, the relationships between ASWJ and trafficking networks may also be expected to shift in future.

Notes

-

Gersende Rambourg and Susan Njanji, Palma jihadist attack turning point in Mozambique crisis, Yahoo News, 30 March 2021, https://news.yahoo.com/palma-jihadist-attack-turning-point-174423653.html. ↩

-

UN News, Mozambique: Cabo Delgado displacement could reach 1 million, UN officials warn, 22 March 2021, https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/03/1087952. ↩

-

ACLED, Zitamar News and Mediafax project Cabo Ligado, weekly brief 15-21 March 2021, https://www.caboligado.com/reports/cabo-ligado-weekly-15-21-march-2021. ↩

-

Andrew Harding, Hungry, angry and fleeing the horrors of war in northern Mozambique, 13 March 2021, BBC News, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-56373651. ↩

-

Save the Children, Children as young as 11 brutally murdered in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique, as conflict intensifies, 16 March 2021, https://www.savethechildren.org.uk/news/media-centre/press-releases/children-as-young-as-11-brutally-murdered-in-cabo-delgado–mozam. ↩

-

Amnesty International, “What I Saw Is Death”: War crimes in Mozambique’s forgotten cape, 2 March 2021, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr41/3545/2021/en/ ↩

-

13 Defence Web, Dyck Advisory Group to investigate after Amnesty says it shot at civilians in Mozambique, 2 March 2021, https://www.defenceweb.co.za/security/national-security/south-african-company-to-investigate-after-amnesty-says-it-shot-at-civilians-in-mozambique/. ↩

-

Andrew Harding, Hungry, angry and fleeing the horrors of war in northern Mozambique, 13 March 2021, BBC, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-56373651. ↩

-

For a summary, see Emilia Columbo, The long-term humanitarian costs of Mozambique’s insurgency, World Politics Review, 18 March 2021, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/29504/in-mozambique-violence-from-isis-affiliate-takes-a-devastating-toll. ↩

-

Rebels seize port in gas-rich northern Mozambique, Al Jazeera, 13 August 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/8/13/rebels-seize-port-in-gas-rich-northern-mozambique. ↩

-

Interview with local source connected to drugs trafficking, Zanzibar, 29 January 2021; WhatsApp message from local source in Maputo, 25 March 2021; information from local source in Tanzania connected to Tanzania coastal drugs traffickers, 10 March 2021. ↩

-

Interview with local source, Pemba, 24 January 2021. ↩

-

Interview with local source, Pemba, 24 January 2021. 19 Interview with retired law enforcement officer, Pemba, 25 January 2021. ↩

-

Interview with local source, Nampula, 20 January 2021. 21 Five girls arrive in Macomia after being freed by starving insurgents, Zitamar News, 16 February 2021, https://zitamar.com/five-girls-arrive-in-macomia-after-being-freed-by-starving-insurgents/. ↩

-

Five girls arrive in Macomia after being freed by starving insurgents, Zitamar News, 16 February 2021, https://zitamar.com/five-girls-arrive-in-macomia-after-being-freed-by-starving-insurgents/. ↩

-

Peter Fabricius, As the conflict rages on, ordinary Mozambicans suffer while officials continue to benefit, Daily Maverick, 28 February 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-02-28-as-the-conflict-rages-on-ordinary-mozambicans-suffer-while-officials-continue-to-benefit/. ↩

-

Mozambique News Reports & Clippings, 530, 24 March 2021, bit.ly/mozamb, accessed 24 March 2021. ↩

-

OCHA, Flash Update, Attacks in Palma District Flash Update No.2, 30/3/21, https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/mozambique/flash-update/yJjRgLZc7DCGXBD7RBHfE/. ↩

-

BBC NewsHour, Mozambique attacks: ‘Insurgents have the upper hand’, 31/3/21, https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p09c4z63; Peter Fabricius, Northern Mozambique: Volunteer ships help to evacuate 1,000 from Palma after insurgent attack, Daily Maverick, 28 March 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-03-28-northern-mozambique-volunteer-ships-help-to-evacuate-1000-from-palma-after-insurgent-attack/. ↩

-

Club of Mozambique, Government forces ‘completely’ in control of Palma – Army, 5 April 2021, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/mozambique-government-forces-completely-in-control-of-palma-army-watch-188551/; Alex Crawford, Mozambique: Bodies in the street and hospital vandalised – Sky News first to see devastation left by extremists, Sky News, 6 April 2021, https://news.sky.com/story/mozambique-bodies-in-the-street-and-hospital-vandalised-sky-news-first-to-see-devastation-left-by-extremists-12266659; Gersende Rambourg and Susan Njanji, Palma jihadist attack turning point in Mozambique crisis, Yahoo News, 30 March 2021, https://news.yahoo.com/palma-jihadist-attack-turning-point-174423653.html; BBC Newshour, Mozambique attacks: ‘Insurgents have the upper hand’, 31 March 2021, https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p09c4z63. ↩

-

For discussion of the geopolitics underlying the strategy of international military engagement in Cabo Delgado, see Mozambique News Reports & Clippings, 516, 18 January 2021, http://www.open.ac.uk/technology/mozambique/news-reports-clippings-2021, accessed 24 March 2021. ↩

-

Declan Walsh and Eric Schmitt, American Soldiers Help Mozambique Battle an Expanding ISIS Affiliate, New York Times, 15 March 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/15/world/africa/mozambique-american-troops-isis-insurgency.html. ↩

-

Christopher Giles and Peter Mwai, Mozambique conflict: Why are US forces there?, 21 March 2021, BBC News, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-56441499 France24, Portugal to send troops to Mozambique after brazen Palma attack by Islamic insurgents, 30/3/21, https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20210330-portugal-to-send-troops-to-mozambique-after-brazen-palma-attack-by-islamic-insurgents?ref=tw_i. ↩

-

Mozambique News Reports & Clippings, 519, 28 January 2021, bit.ly/mozamb, accessed 24 March 2021. ↩

-

See, for example, Joseph Hanlon, How Mozambique’s smuggling barons nurtured jihadists, BBC, 2 June 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-44320531. ↩

-

GI-TOC, Risk Bulletin of Illicit Economies in East and Southern Africa, issue 7, April–May 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/esaobs-risk-bulletin-7/. ↩

-

Interview with former law enforcement officer, Pemba, 53 24 January 2021; Interview with senior NGO worker from Niassa Province, Pemba, 22 January 2021. ↩

-

Civil Society Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa, Risk Bulletin 7, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, April–May 2020, 54 https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/esaobs-risk-bulletin-7/. ↩

-

Interview with former law enforcement officer, Pemba, 24 January 2021. ↩

-

Two further events contributed to ASWJ recruitment in this area: firstly, in 2016 artisanal mining without a 56 licence was criminalized, and secondly, in February 2017, Mozambican police undertook a large-scale operation 57 to clamp down on illegal miners and 3 600 people were arrested. Around two-thirds of those arrested were foreigners, mostly Tanzanian, who were then deported. This led to recruitment from this Tanzanian group in particular. See News24, Ruby rush brings gangland turf war to Mozambique, 29 March 2017, https://www.news24.com/Africa/News/ruby-rush-brings-gangland-turf-war-to-mozambique-20170329. ↩

-

Civil Society Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa, Risk Bulletin 7, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, April–May 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/esaobs-risk-bulletin-7/. ↩

-

Mozambique News Reports & Clippings, 522, 9 February 2021, bit.ly/mozamb, accessed 24 March 2021. ↩

-

US Department of State, Digital Press Briefing on U.S. Efforts to Combat Terrorism in Africa, 11 March 2021, https://www.state.gov/digital-press-briefing-on-u-s-efforts-to-combat-terrorism-in-africa/. ↩

-

See work under the CovidCrimeWatch initiative, by the Global Initiative Against Organized Crime, https://globalinitiative.net/initiatives/covid-crime-watch/. ↩

-

Interview with international law enforcement source 61 Maputo, 11 January 2021; interview with international law enforcement source Zanzibar, 28 January 2021. ↩

-

Interview with former law enforcement officer, Pemba, 24 January 2021. ↩

-

Jason Eligh, A Synthetic Age: The Evolution of Methamphetamine Markets in Eastern and Southern Africa, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized 63 Crime, March 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/meth-africa/. ↩

-

Interview with law enforcement source, Maputo, 15 January 2021. ↩

-

Mozambique News Reports & Clippings, 522, 9 February 2021, bit.ly/mozamb, accessed 24 March 2021 (also via Zitamar News); interview with local source connected to drugs trafficking, Zanzibar, 29 January 2021; interview with local source knowledgeable of the northern 65 Mozambique drugs trade, Maputo, 12 January 2021. ↩

-

Mozambique News Reports & Clippings, 522, 9 February 2021, bit.ly/mozamb, accessed 24 March 2021. ↩

-

Information and pictures received from a local source in Maputo with connections to the National Criminal Investigations Service (SERNIC), 25 March 2021. ↩

-

Polícia moçambicana apreende quantidade milionária de heroína, DW, 20 March 2021, https://www.dw.com/pt-002/pol%C3%ADcia-moçambicana-apreende-quantidade-milionária-de-hero%C3%ADna/a-56937863. ↩

-

Signal conversation with local source knowledgeable of the northern Mozambique drugs trade, 20 March 2021. ↩

-

Mozambique: PRM seizes 95 kg of hard drugs in Nampula, Club of Mozambique, 10 March 2021, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/mozambique-prm-seizes-95-kg-of-hard-drugs-in-nampula-watch-186418/. ↩

-

Droga desaparece em Nacala poucas horas após a sua apreensão, Carta de Moçambiwue, 26 February 2021, https://cartamz.com/index.php/politica/item/7337-droga-desaparece-em-nacala-poucas-horas-apos-a-sua-apreensao. ↩

-

Mozambique News Reports & Clippings, 522, 9 February 2021, bit.ly/mozamb, accessed 24 March 2021. ↩

-

DefenceWeb, French frigate Nivoes seizes half a ton of drugs off Mozambique, 28 January 2021, https://www.defenceweb.co.za/security/maritime-security/french-frigate-nivose-seizes-half-a-ton-of-drugs-off-mozambique/. ↩

-

Interviews with a local source familiar with northern Mozambique drugs trafficking networks, Pemba, January 2020 and January 2021. ↩

-

Interview with local source connected to drugs trafficking, Zanzibar, 29 January 2021. ↩

-

Interview with local source connected to drugs trafficking, Zanzibar, 29 January 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with former and active drugs mules, Zanzibar, 29 January 2021; Signal conversation with local source knowledgeable of the northern Mozambique drugs trade, 25 March 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with former and active drugs mules, Zanzibar, 29 January 2021; Signal conversation with local source knowledgeable of the northern Mozambique drugs trade, 24 January 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with a local source familiar with northern Mozambique drugs trafficking networks, Pemba, January 2020 and January 2021; interview with former law enforcement officer, Pemba, 24 January 2021. ↩

-

Simone Haysom, Peter Gastrow and Mark Shaw, June 2018, The heroin coast: A political economy along the eastern African seaboard, ENACT, https://globalinitiative.net/the-heroin-coast-a-political-economy-along-the-eastern-african-seaboard/. See also Joseph Hanlon, The Uberization of Mozambique’s heroin trade, Working Paper Series 18-190, London School of Economics and Political Science, July 2018, http://www.lse.ac.uk/international-development/Assets/Documents/PDFs/Working-Papers/WP190.pdf. ↩

-

Interview with former law enforcement officer, Pemba, 24 January 2021. ↩

-

Alastair Nelson, A triangle of vulnerability: Changing patterns of illicit trafficking off the Swahili coast, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 15 June 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/triangle-vulnerability-swahili-coast/. ↩

-

Interviews with a local source familiar with northern Mozambique drugs trafficking networks, Pemba, January 2020 and January 2021; interview with a SERNIC officer, Montepuez, 23 January 2021. ↩

-

Alastair Nelson, A triangle of vulnerability: Changing patterns of illicit trafficking off the Swahili coast, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 15 June 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/triangle-vulnerability-swahili-coast/. ↩

-

Sally Hayden, Deaths of 64 migrants in Mozambique turns spotlight on intra-Africa smuggling, Irish Times, 26 March 2020, https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/africa/deaths-of-64-migrants-in-mozambique-turns-spotlight-on-intra-africa-smuggling-1.4213321. ↩

-

Mozambique: Cabo Delgado again registers influx of illegal immigrants – O País, Club of Mozambique, 16 December 2020, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/mozambique-cabo-delgado-again-registers-influx-of-illegal-immigrants-o-pais-180179/; ACLED, Zitamar News and Mediafax project Cabo Ligado, weekly brief 18–24 January 2021, https://www.caboligado.com/reports/cabo-ligado-weekly-18-24-january. ↩

-

Interview with a source who has close contact with an LAM ground staff member in Nairobi, 31 January 2021; interview with Migration Services official, Pemba, 17 January 2021. ↩