New findings on the supply of methamphetamine from Afghanistan to South Africa.

Meth consumption has long been ignored as a domestic drug problem in East and southern Africa. However, new GI-TOC research has found that the drug is far more embedded across the region than previously understood.1

South Africa is home to the largest and most established meth consumption market in East and southern Africa. A new flow of meth to South Africa appears to have emerged out of Afghanistan, with the aim of feeding the growing base of southern African users. These growing international flows, and the scale of southern African meth consumption, may have longstanding impacts on urban governance in the region.

The rise of meth consumption in South Africa

Meth consumption has a long history in South Africa, dating back to the early days of the democratic transition (and with roots in the apartheid period). The first meth laboratory was seized in South Africa in 1998, shortly after the use of meth was first detected in Cape Town.2 By 2005, eight years after its appearance, meth became the primary substance of use among all people who use drugs (PWUD) in the Western Cape province,3 surpassing methaqualone, cannabis and even alcohol.4 Today, meth is still the most common drug of choice in the Western and Eastern Cape provinces and the second most common in the Northern Cape, North West and Free State provinces.

South Africa’s three major meth supply chains

Today, South African meth is sourced from three major supply chains. The first originates in Nigeria and is imported by Nigerian syndicates, although since 2016 these syndicates appear to have been producing meth in Nigeria itself, allegedly in cooperation with at least one of the Mexican cartels.5 High-quality Nigerian-made crystal meth has flooded the South African market and is known among PWUD as ‘Mexican meth’ due to the alleged Mexican connection.

Figure 4 Tracking meth and alcohol as reported primary substances of use (by percentage) in Western Cape province, South Africa, 2000–2018.

SOURCE: Siphokazi Dada et al., Monitoring alcohol, tobacco and other drug use trends in South Africa (July 1996 to December 2018), South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU), 22, 1, 2019, 15

Figure 5 Dominance of methamphetamine use by province in South Africa, 2019.

SOURCE: Data derived from SACENDU regional reports for July to December 2018 and 2019. Most recent figure available was used for each province.

A second, locally manufactured supply also serves domestic and regional markets. This supply is linked to Chinese syndicate interests and originates in the greater Johannesburg area. However, the number of clandestine domestic meth laboratories detected by the South African Police Force has decreased significantly over the past six years. This appears to correspond with information from suppliers in Gauteng and Western Cape who indicate that Chinese-supported meth production has declined in South Africa in recent years. (This gradual decrease in domestic South African meth manufacture, and the rise of industrial production locations in West Africa that are supplying the South African meth market, is a finding also supported by UN, INTERPOL and US sources.6)

A third international flow of meth to South Africa came to light in South Africa’s domestic meth markets in late 2019, particularly in the Western Cape region. This is a meth supply chain that originates in the Afghanistan–Pakistan border region, with interviewees calling the product ‘Pakistani meth’.7 The emergence of this new source of meth follows a significant shift to the production of meth in Afghanistan’s opium-poppy-growing south-west provinces along the borders with Iran and Pakistan.8

As we reported in Issue 12 of this bulletin, the existence of this new ‘Pakistani meth’ supply was confirmed by several Cape Town users and distributors during research conducted in August 2020.9 Mixed seizures of meth and heroin shipments along the ‘southern route’ – usually used to traffic heroin from the Pakistan coast to East and southern Africa – also suggested that this route was increasingly being used for meth trafficking.10

The emerging picture of the ‘Pakistani meth’ supply chain to South Africa

Since our first report,11 more than a dozen informants, including both intermediate and high-level meth importers as well as rival (Nigerian) importers, have now confirmed the existence of a Pakistani-controlled meth flow. Eight distributors in the Western Cape area made (unprompted) claims that a new Pakistan-based meth supply chain was feeding the South African market.12 One informant stated that this Pakistani meth supply had ‘hit the Cape big time’.13 Another South African-based importer confirmed that he placed his Afghan meth orders by phone directly with intermediaries in Pakistan.14

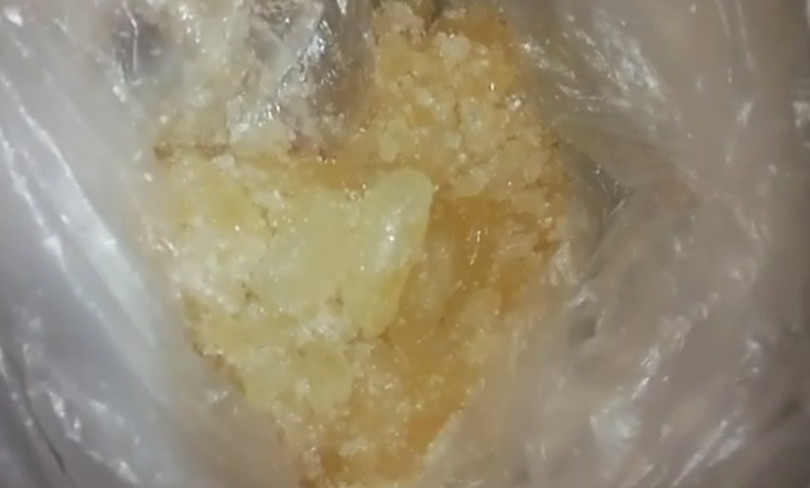

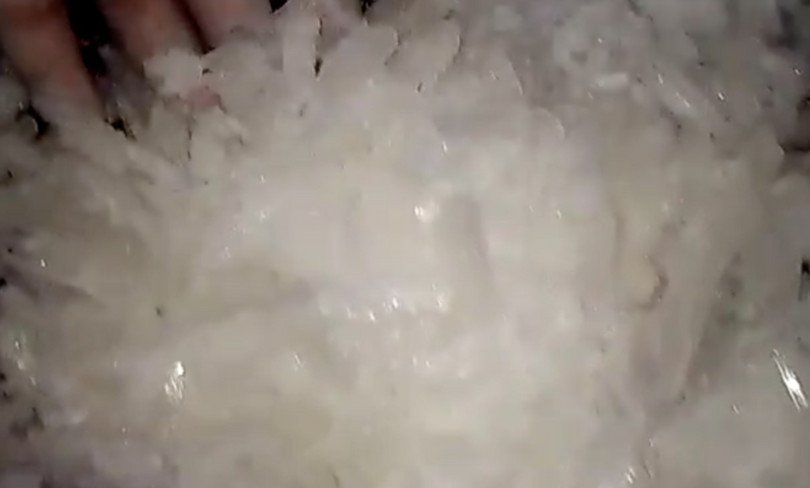

Afghan meth shipments that have arrived in South Africa. A South African- based importer confirmed that he placed his Afghan meth orders by phone directly with intermediaries in Pakistan.

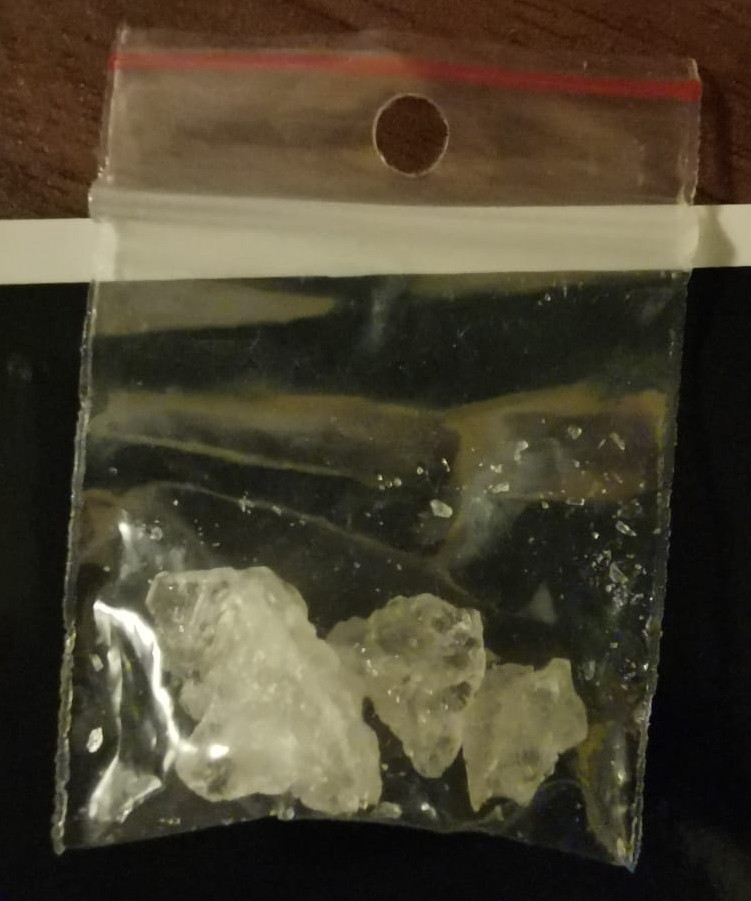

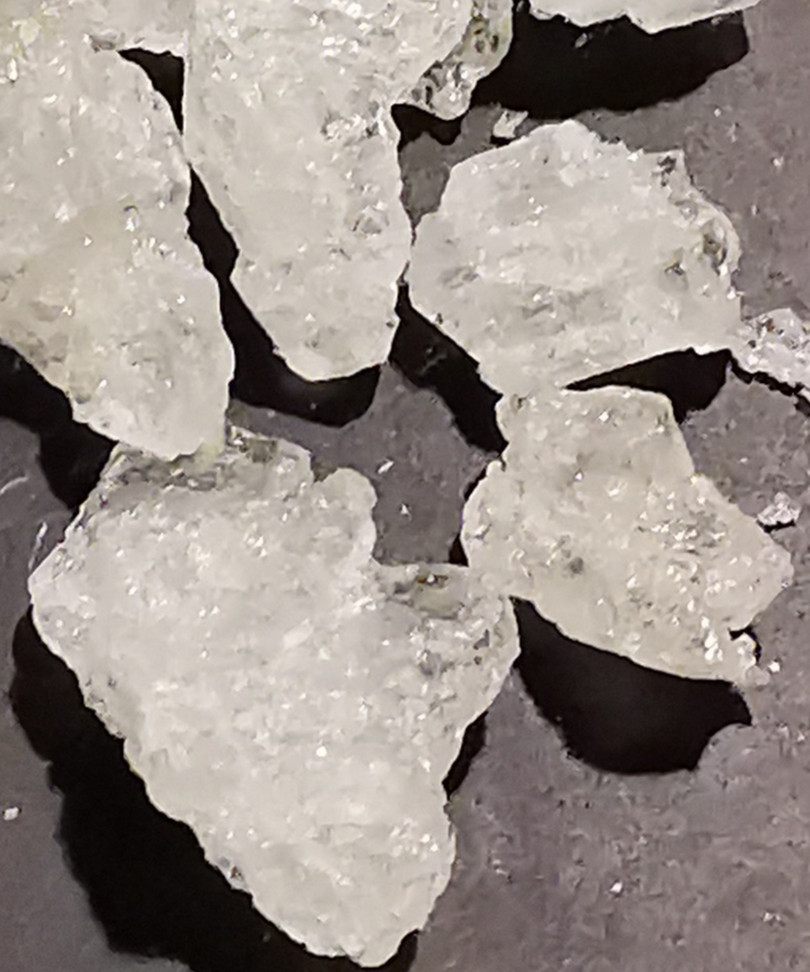

‘Mexican meth’, produced in Nigeria and imported by Nigerian distributors, has been available in South Africa for the last three to four years. This quality of meth is distinguishable by its large crystalline shards.

Dozens of PWUD in South Africa have confirmed that this ‘new’ meth is clearly different in texture, purity and synthesis base (in that this type of meth is derived from the ephedra plant, which grows widely in Afghanistan, rather than other common chemical precursors) to other supplies. No other meth supply chain was ever identified in any of the interviews throughout the research period (May to November 2020) other than the three described above: domestic meth (Chinese-supported), Mexican meth (Nigeria-based) and the new Afghani meth.15

The types of meth are visually distinct: Mexican meth appears to be consistently clean, translucent and pure. Pakistani meth, which is ephedra based, appears in the marketplace in both large crystalline shards, similar to those of Mexican meth, as well as in batches of smaller ‘crushed ice’ crystals that can be oily and often retain a yellow or brown hue (i.e. unrinsed meth). The quality of this new meth can be variable, according to PWUD in South Africa, but normally is comparable to the best Mexican meth – an attribute that has increased demand for the new supply. Locally produced South African meth is distinguished by its generally smaller (‘crushed ice’) crystal size, a more regular white-ish or duller, cloudy appearance and the irregular presence of large crystalline shards. This is perceived to be of lower quality and there is a strong belief among PWUD that some of the local meth often is adulterated with an external agent.

Our research found two Pakistani meth supply chains into South Africa. The first runs by sea (via dhows, Indian Ocean fishing vessels) to a Middle Eastern nation, from which it then transits via a popular air hub onboard a regularly scheduled passenger flight. The first routing appears to involve the supply of small amounts at a time (perhaps in the low tens of kilograms), most likely destined for a single local Cape Town syndicate.

The second route is by sea (by both dhow and container ship) to the Angoche–Pemba coastline area in the north of Mozambique, then overland to Johannesburg and Cape Town in South Africa. This route sees meth supplied in volumes of hundreds of kilograms, as evidenced by increased meth seizures in the western Indian Ocean region, including off the coast of eastern and southern Africa and of combined shipments of meth and Afghan heroin, primarily by the international naval force CTF 150.

In October 2020, the CTF 150 seized 450 kilograms of meth from a dhow heading for the East African coast – a record for the amount of meth seized in a single instance.16 In November 2020, the Yemeni Coast Guard, with assistance from the Arab coalition forces, seized a dhow off the Mahra coast carrying 216 kilograms of meth.17 Another large seizure of heroin, meth and hashish was made in the Arabian Sea in February 2021.18 No seizures of similar shipments were reported before late 2019.19

Pakistani meth is also being reported in other regions. Sri Lankan, Indonesian and Australian authorities have confirmed seizures of Afghan meth shipments, while reports of meth importation by Pakistani and Iranian crews have been verified in Tanzania and Mozambique. In Mozambique, chemical analysis conducted on samples of this new meth supply have confirmed its origin to be Afghanistan.20

The future of southern Africa’s meth market

With the establishment of the new Pakistani meth supply chain, southern Africa is now a node in the global meth supply chain connecting both the cartels of Mexico in the west (via the Nigerian syndicates) and the Taliban-controlled provinces of Afghanistan in the east, where the meth imported via Pakistan is originally produced.

This evolution should not be a surprise. South Africa’s synthetic drugs market has a long history and has grown to be one of the largest meth consumer markets in the country – and is still growing. In the region as elsewhere, meth markets have been driven, among other factors, by urban decay and criminal governance in communities that have long been marginalized. The repercussions of the coronavirus pandemic and the economic consequences of lockdown may push these communities further to the margins.21 This confluence of factors looks set to sustain and increase the market for synthetic drugs, including meth, across East and southern Africa in the near future.

The research presented in this article is drawn from ‘A synthetic age: The evolution of methamphetamine markets in eastern and southern Africa’, a new research report by Jason Eligh for the GI-TOC’s Observatory of Illicit Economies in East and Southern Africa, due to be published in March 2021.

Notes

-

Jason Eligh, A Synthetic Age: The Evolution of Methamphetamine Markets in Eastern and Southern Africa, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, March 2021 (forthcoming). ↩

-

United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention (UNODCCP), South Africa country profile on drugs and crime: part 1: drugs, 1999. ↩

-

The drug primarily emerged on the Western Cape coast due to a barter arrangement between Cape gangs and Chinese crime syndicates exchanging cheaply acquired precursor chemicals for poached abalone. This arrangement is described in detail in Jason Eligh, A Synthetic Age: The Evolution of Methamphetamine Markets in Eastern and Southern Africa, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, March 2021 (forthcoming). ↩

-

SACENDU reports indicate that meth surpassed alcohol as the primary substance of use in the Western Cape in the second half of 2005. Siphokazi Dada et al, Research brief: Monitoring alcohol, tobacco and other drug use trends in South Africa (July 1996–December 2018), SACENDU, Pretoria, 22, 1, 2019, 15. In the latest figures available, SACENDU reports that methamphetamine (39%), cannabis (39%) and alcohol (33%) remain the most used substances in the Western Cape. SACENDU, Monitoring alcohol, tobacco and other drug abuse treatment admissions in South Africa, Phase 45, South Africa Medical Research Council, October 2019, 8. It is important to note that this data is based upon metrics grounded in information gathered from the subset of PWUD who entered treatment services during the reporting period. Whether these SACENDU numbers are an accurate representation of wider drug market consumption characteristics is a point for consideration. ↩

-

Interviews with Nigerian and other local distributor informants. ↩

-

United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime, Transnational organized crime in West Africa: a threat assessment, 2013, p 23; US Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement, International narcotics control strategy report: Volume 1: Drug and chemical control, March 2020, p 201; INTERPOL, Operation targeting drug trafficking nets couriers in Latin America and Africa, INTERPOL press release, 8 October 2015, https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2015/Operation-targeting-drug-trafficking-nets-couriers-in-Latin-America-and-Africa. ↩

-

‘Pakistani meth’ is a misnomer of sorts. The meth is more likely supplied by a syndicate composed of South Asians who share a common language and religion. While Pakistanis do appear to make up a sizeable cohort of this group, the group should not be viewed as being exclusively Pakistani in nationality. It could include individuals of Indian, Iranian and Afghani origin, as well as several other nationalities. ↩

-

Subsequent analysis by David Mansfield on behalf of the European Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) has concluded that ‘the ephedrine and methamphetamine industry has emerged in Afghanistan and there are now indications of international exports suggesting that the country is beginning to penetrate international markets’. EMCDDA, Emerging evidence of Afghanistan’s role as a producer and supplier of ephedrine and methamphetamine, EU4MD special report, November 2020. See also Under the shadow: Illicit economies in Iran, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, October 2020. ↩

-

Civil Society Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa: Risk Bulletin 12, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, September–October 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/GI-TOC-ESAObs-RB12.pdf. ↩

-

Dan Meyer, Truck driver caught with R30 million drug cargo at Mozambique border, South African, 25 May 2020, https://www.thesouthafrican.com/news/drug-bust-mozambique-heroin-meth-cocaine/. ↩

-

Since our initial reporting on the existence of a Pakistan-based meth supply chain, additional follow-up interviews were conducted in an attempt to validate these claims through unrelated sources. These included interviews with meth importers and high-level distributors, conducted through October and November 2020. ↩

-

Interviews conducted in October 2020. ↩

-

Informant C, personal communication, June 2020. ↩

-

Interview, October 2020. ↩

-

Malaysia was identified as a meth source by a distributor in Cape Town; however, no additional information to support the plausibility of this claim could be identified prior to the writing of this article. Research continues. ↩

-

Combined Maritime Forces, Combined maritime forces seizes over 450kg drugs in its largest methamphetamine drug bust, 21 October 2020, https://combinedmaritimeforces.com/2020/10/21/combined-maritime-forces-seizes-over-450kg-drugs-in-its-largest-methamphetamine-drug-bust/. ↩

-

Saeed Al-Batati, Boat carrying 1 000 kg of drugs seized by Yemeni Coast Guard, Arab News, 14 November 2020, https://www.arabnews.com/node/1763121/middle-east. ↩

-

Combined Maritime Forces, HMS Montrose seizes over $15 million worth of narcotics in Arabian Sea, 17 February 2021, https://combinedmaritimeforces.com/2021/02/17/hms-montrose-seizes-over-15-million-worth-of-narcotics-in-arabian-sea/. ↩

-

International naval forces operating as part of the Combined Task Force 150 (CTF 150) reported a significant increase in meth seizures in 2019 in their area of operations, which encompasses a wide swathe of the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Aden. ↩

-

Senior law enforcement source in Mozambique, January 2021. ↩

-

See Jason Eligh, A Synthetic Age: The Evolution of Methamphetamine Markets in Eastern and Southern Africa, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, March 2021 (forthcoming). ↩