Why did two major ivory trafficking cases in Tanzania collapse, with one conviction quashed and the other resulting in only a small fine?

Developments in two major ivory trafficking cases in Tanzania are not what conservationists might have hoped for. The conviction of Boniface Mathew Malyango, known as ‘Shetani Hana Huruma’ (‘the Devil has no mercy’ in Kiswahili), was hailed by conservation organizations as a victory in 2017,1 with Shetani described as one of the ‘biggest ever illegal ivory traders’.2 However, his conviction was quietly overturned in mid-2020: a development that went largely unreported in the press.

Likewise, Mateso ‘Chupi’ Kasian was extradited from Mozambique to Tanzania in 2017 to face prosecution in what was, at the time, seen as a major victory for regional cooperation against wildlife trafficking. However, his prosecution only led to a TZS 500 000 (US$215) fine – a small sum compared to the enormity of the trafficking operation he supposedly controlled. 3

Both cases highlight the significant challenges that major wildlife trafficking investigations often face, including corruption, delays in prosecution and poor evidence handling. Support and political pressure from international partners and NGOs have primarily focused on arrests and initial prosecutions, rather than on the follow-up to legal cases.

The Shetani case

Shetani became globally infamous as a result of the Leonardo DiCaprio-produced documentary The Ivory Game and was reputed to have killed or ordered the killing of up to 10 000 elephants, and to have controlled poaching gangs in Tanzania, Burundi, Mozambique, Zambia and southern Kenya. He was arrested with his two brothers in October 2015 in Tanzania and convicted in 2017 on charges of ‘leading organized crime’ and ‘unlawful dealing in government trophies’.4 The particulars of the case charged Shetani with collecting, transporting and selling 118 elephant tusks worth almost US$1 million. He and his brothers were sentenced to 12 years in prison.5

Conservation NGOs welcomed Shetani’s conviction as a sign that Tanzania was taking a stance on ivory trafficking. ‘This prosecution sends out a strong message that Tanzania’s authorities are taking [poaching] seriously and are working to eliminate poaching in the country’, said Amani Ngusaru, WWF-Tanzania country director, in a statement at the time.6

However, in a judgment on 18 June 2020, the Court of Appeal of Tanzania in Dodoma quietly quashed the convictions of Shetani and his brother, Lucas Mathayo Malyango.7 There was almost no media coverage of the appeal case.8

Boniface Mathew Malyango, known as ‘Shetani’, was alleged to be one of the major ivory traffickers operating in East Africa.

Photo: Terra Mater Factual Studios / The Ivory Game

The initial prosecution had relied on three key pieces of evidence: 1) a confession that Shetani made to police officers upon his arrest that he was involved in the ivory trade; 2) a caution statement where he again confessed to police and described how he used special compartments in his modified cars to transport pieces of ivory; and 3) physical evidence taken from Shetani’s car, in which a whitish substance had been found that was determined by a sniffer dog and then by chemical analysis to be ivory shards.

In an appeal to the High Court, the first appeal judge had expunged the caution statement, on the grounds that it was not properly determined that it was given voluntarily. In the Court of Appeal hearings, the State attorney conceded that this caution statement was presented by the prosecution in the hope that it would prove that Malyango dealt in the 118 ivory tusks in question. It was, in short, a key piece of evidence connecting Malyango to a criminal enterprise.

The Court of Appeal judge then found that the physical evidence from the sniffer dog and chemical analysis, showing ivory shards found in the car, would also have to be discounted. The chain of custody of the car had been broken since it was searched only several hours after the car was seized, after it had been driven to a police station in Dar es Salaam.

The Court of Appeal judge also ruled that, while Shetani’s oral confession to police was admissible evidence, it was not enough for a conviction by itself. Without the physical evidence from the car, the judge found that there was insufficient proof that Shetani was part of an organized crime group involved in the collection and sale of the ivory in question.

According to Shamini Jayanathan, a Kenya-based criminal barrister working on illegal wildlife trafficking, the appeal judgment points out several major evidential problems: a lack of forensic examinations, issues with chains of custody in key evidence and the over-reliance on confessions. ‘The basics of “points to prove” seem to have been missed, with no evidence adduced of key elements of the offence’, such as transport, collection or sale of the ivory, says Jayanathan.9

In her view, this stems from issues with police training. ‘In my experience, there is very little training done on interviews of suspects and the need to build a case regardless of what a suspect may say. There are no measures of recording of interviews or codes of practice regarding treatment of suspects (and ideally, video recording of their interviews in police detention) to contradict allegations of mistreatment or pressure.’ Where international support and mentoring is provided for wildlife trafficking cases, this is primarily focused on wildlife agencies and not the national police.

Other experts monitoring wildlife trafficking cases in East Africa also argued that the other elements of the case that posed problems – such as presenting testimony from sniffer dog handlers or maintaining proper chain of custody over physical evidence – also indicate issues with police training.

‘Shetani’ has since been released from custody, as his conviction has now been quashed by the highest court in Tanzania.

The Mateso case

In late November 2020, a judgment was made in an appeal case in the High Court of Tanzania at Mtwara, a small port city near the Mozambique border.10 The appeal was filed by Tanzania’s Director of Public Prosecutions against Mateso Kasian (also known as ‘Chupi’ which means ‘underwear’ in Kiswahili), with the aim of increasing the penalty of his 2019 conviction on ivory trafficking charges.

Mateso had been sentenced to pay a fine of TZS 500 000 (US$215) and to forfeit two houses in Dar es Salaam and Liwale. This, the prosecutors argued, was insufficient, since the guidelines for sentencing this offence under Tanzania’s wildlife crimes legislation recommend a fine of no less than twice the value of the ‘trophy’ or wildlife product involved: in this case, TZS 777 600 000 (US$335 000).

The judge disagreed: the ruling stated the prosecution’s case was baseless, since (despite Mateso’s long, documented history of arrests and involvement in wildlife trafficking) he had no previous wildlife trafficking convictions, he had pled guilty and because the ‘recommended fine’ is not a mandatory sentence. Not only that, but the judge found that the original order for forfeiture of Mateso’s houses did not properly specify the properties, and so was quashed. As such, the TZS 500 000 fine remained the only penalty. The judgement did not describe the reasons why the penalty imposed differed so much from the recommended fine, even if such a fine is not ‘mandatory’.

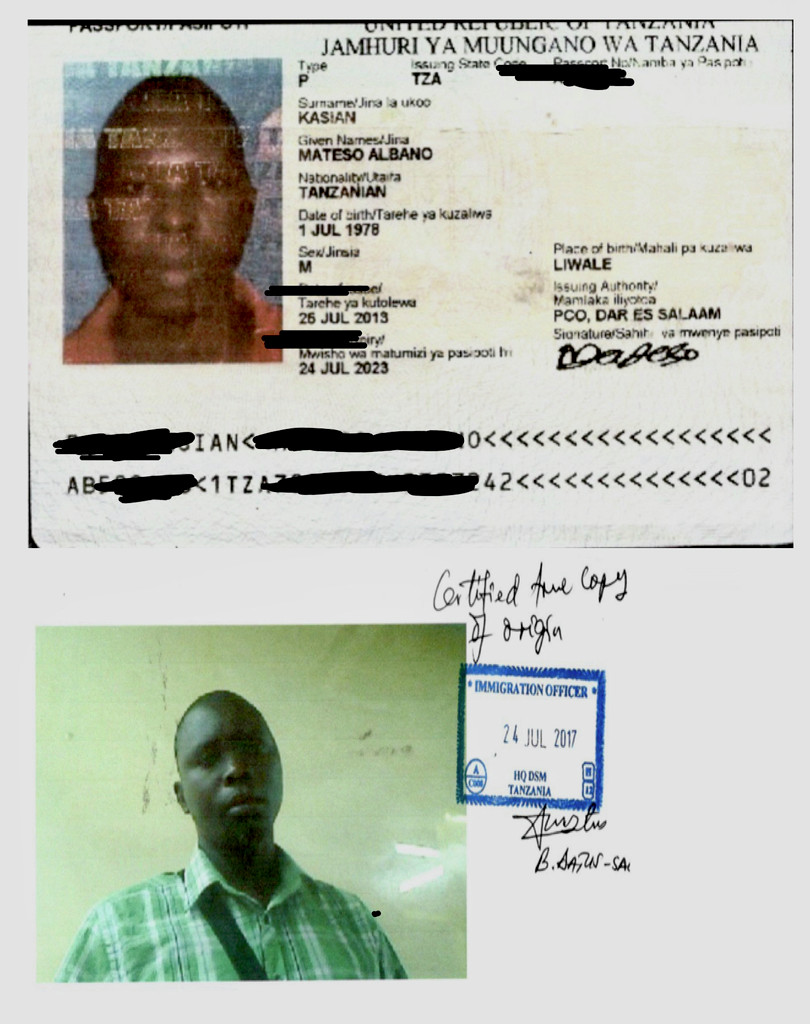

Ivory trafficker Mateso ‘Chupi’ Kasian’s passport, certifying that he is a Tanzanian citizen. He was deported from Mozambique after serving a short sentence relating to a fraudulently acquired Mozambican identity card.

Photo: Supplied

Mateso ‘Chupi’ Kasian after his deportation to Tanzania, where he was then taken into custody on ivory trafficking charges in 2017.

Photo: Supplied

The prosecution brought against Mateso was the product of years of work on behalf of Tanzanian and Mozambican investigators and conservation NGOs,11 investigating him for orchestrating the slaughter of hundreds, possibly thousands, of elephants in southern Tanzania and Mozambique since 2012.12

Mateso, a Tanzanian national, was reportedly originally running elephant-poaching gangs in southern Tanzania. According to coverage of his trial in 2018 in Lindi, Mateso was arrested in 2008 in possession of elephant ivory in Liwale, southern Tanzania, before evading capture and escaping over the border to Mozambique.13

Mateso then shifted his operation to Mozambique, reportedly in order to evade investigations by Tanzania’s National and Transnational Serious Crimes Investigation Unit (NTSCIU), between 2013 and 2014. Having fraudulently obtained a Mozambican identity card, he settled in northern Mozambique and allegedly directed numerous elephant-poaching gangs in Niassa Special Reserve at the height of the elephant-poaching crisis in the area.14

In September 2014, a poaching gang was arrested near Niassa Special Reserve in possession of a notebook detailing Mateso’s name in connection with a 300-kilogram shipment of ivory. Interviews with suspects suggested that he was running up to five poaching gangs in the park, which were highly organized and well-equipped. Mateso was reportedly supplying ivory to both Chinese and Vietnamese trafficking syndicates moving ivory out of Mozambique.15

These developments were followed by over two years’ work by Mozambique’s National Criminal Investigation Service (SERNIC), Mozambique’s National Administration of Conservation Areas and Tanzania’s NTSCIU, and conservation organizations including the Wildlife Conservation Society, the PAMS Foundation and Luwire Conservancy. Mateso was taken into custody by SERNIC in northern Mozambique on 11 July 2017.16

During these investigations it apparently became clear that Mateso was well protected by corrupt police and local government officials.17 The decision was made by the Mozambican authorities that, due to the risk of corruption impeding a wildlife trafficking prosecution, Mateso would only be charged in Mozambique over his fraudulently acquired identity card. Following a short spell in prison in Mozambique on the identity fraud charges, Mateso was deported to Tanzania, where he then faced wildlife trafficking charges.

At the time, this was seen as a major victory for regional cooperation, for conservation NGOs supporting wildlife trafficking prosecutions and for circumventing corruption issues. The enormity of the work involved in prosecuting Mateso, and the extent of the wildlife offences he has reportedly been responsible for, are at odds with the ultimate result of his prosecution. He remains in custody pending the decision of the Court of Appeal, and the outcome of another pending case with the Resident Magistrate Court at Lindi.

From 2009 to 2014, Mozambique lost nearly half its elephants – including this one in Niassa Special Reserve – to poaching. Mateso ‘Chupi’ Kasian was accused of running several poaching gangs operating within the reserve.

Photo: Alastair Nelson

Figure 1 Highlighted ivory trafficking cases in Tanzania, 2015–2020.

NOTE: The arrests of Boniface Mathew Malyango, Mateso ‘Chupi’ Kasian and Yang Feng Glan were hailed as some of the most significant arrests of ivory traffickers in East Africa.

Lessons learned from the Mateso and Shetani cases

Both Shetani and Mateso were landmark cases challenged by corruption – a challenge that continues to bedevil wildlife trafficking investigations in the region and globally. Corruption of key officials in Mozambique was the reason Mateso was deported to Tanzania rather than facing trafficking charges, but this left the Tanzanian authorities facing the quandary that Mateso’s most recent ivory-poaching activities were in Mozambique, outside their jurisdiction. Corruption was also key in enabling ‘Shetani’ to run his alleged smuggling operation at such a large scale.18

The problems of evidence-gathering (which brought down the Shetani prosecution) have also been seen in other major cases in the region, including several in Kenya.19 As Jayanathan’s assessment of the Shetani appeal suggests, this may be linked to systemic issues of police training.

Both cases faced long delays in prosecution proceedings, with judgments made years after the initial arrest for criminal activity that stretched back many years. Similar delays have been seen in other significant ivory trafficking cases in East Africa.20 These delays pose a serious challenge to prosecutors bringing credible evidence and reliable witnesses to trial.

Questions can also be raised in both cases about the penalties applied. In Tanzania, offences relating to dealing in ivory (for which both Shetani and Mateso were convicted) not only fall under wildlife conservation legislation but are also treated as ‘economic crimes’, following amendments to Tanzania’s Economic and Organized Crime and Control Act (EOCCA). The penalty under the EOCCA for such offences is between 20 and 30 years imprisonment, yet this was not applied in either case.21

It should be noted that other sentences in major ivory trafficking cases in Tanzania have been upheld. A judgment on an appeal of Malyango’s ivory trafficking network, judged in the same week as his own appeal, upheld the charges against his associates.22 Similarly, an appeal in the case of Yang Feng Glan – a notorious ivory trafficker known as ‘the Ivory Queen’ – and her associates was struck down in its entirety in December 2019.23

These cases highlight the challenges in investigating and successfully prosecuting cases against suspected organized wildlife criminals in countries with weak rule of law and entrenched corruption. The efforts required to overcome the corrupt environment and build a case that leads to an arrest and successful prosecution are immense. Yet more can be done to build the capacity of investigators and the prosecutors to build the cases more effectively, on meaningful charges, to ensure that they do not later collapse in court or on appeal. Support, observation and political pressure by civil society, throughout the full legal process, also plays a role.

Notes

-

Shreya Dasgupta, Notorious elephant poacher, ‘The Devil’, sentenced to 12 years in jail, Mongabay, 9 March 2017, https://news.mongabay.com/2017/03/notorious-elephant-poacher-the-devil-sentenced-to-12-years-in-jail/. See also this obituary of PAMS Foundation founder Wayne Lotter (who was assassinated in connection with his work) which describes the Malyango case as one of his greatest achievements): Ben Taylor, Obituary, Tanzanian Affairs, 119, 1 January 2018, https://www.tzaffairs.org/category/obituaries/. ↩

-

See Peadar Brehony, Turning the Tide Against Poaching: Lessons from Tanzania, The Courant, 17 November 2016. ↩

-

Mateso’s sentence was to a TZS 500 000 fine, or in default of payment of the fine a twenty (20) years term of imprisonment. The fine has since been paid in full, meaning Mateso is not liable to the imprisonment. Conversion of currency via Oanda. ↩

-

Boniface Mathew Malyango & Another vs Republic (Criminal Appeal No.358 of 2018) [2020] TZCA 314; (18 June 2020), https://tanzlii.org/tz/judgment/court-appeal-tanzania/2020/314-0. Leading Organized Crime—contrary to Paragraph 14 (1) (a) of the First Schedule to and section 57 (1) and 60 (2) of the Economic and Organized Crime Control Act, Cap. 200); and (2) Unlawful Dealing in Trophies— contrary to section 80 (1) and 84 (1) of the Wildlife Conservation Act No. 5 of2009 read together with paragraph 14 (b) of the First Schedule to and section 57 (1) of the Economic and Organized Crime Control Act, Cap. 200). ↩

-

Shreya Dasgupta, Notorious elephant poacher, ‘The Devil’, sentenced to 12 years in jail, Mongabay, 9 March 2017, https://news.mongabay.com/2017/03/notorious-elephant-poacher-the-devil-sentenced-to-12-years-in-jail/. ↩

-

WWF, Tanzania’s most wanted elephant ivory trafficker sentenced to 12 years in prison, 3 March 2017, https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?293990/ivory_trafficker_sentenced. ↩

-

Boniface Mathew Malyango & Another vs Republic (Criminal Appeal No.358 of 2018) [2020] TZCA 314; (18 June 2020), https://tanzlii.org/tz/judgment/court-appeal-tanzania/2020/314-0. ↩

-

Faustine Kapama, Court acquits two once jailed suspect poachers, Daily News, 31 July 2020, https://www.dailynews.co.tz/news/2020-07-315f23c9bd2f7eb.aspx. This is the only press coverage found on this acquittal. ↩

-

Shamini Jayanathan, email correspondence, 18 February 2021. ↩

-

Director of Public Prosecutions versus Mateso Albano Kasian@Chupi (Criminal Appeal No.29 of 2020) [2020] TZHC 4205; (18 November 2020), https://tanzlii.org/tz/judgment/high-court-tanzania/2020/4205-0. ↩

-

Information on the investigation into Kasian provided by Alastair Nelson, senior analyst at the GI-TOC, former Regional Coordinator for the Wildlife Conservation Society, an NGO involved in building the prosecution against Kasian. ↩

-

Ivory kingpin arrested in Mozambique, WCS Newsroom, 27 July 2017, https://newsroom.wcs.org/News-Releases/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/10414/Ivory-Kingpin-Arrested-in-Mozambique.aspx. ↩

-

‘Chupi’ matatani Lindi, East Africa TV, 21 January 2018, http://www.eatv.tv/news/current-affairs/chupi-matatani-lindi. ↩

-

See Civil Society Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa: Risk Bulletin 5, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, February–March 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/esaobs-risk-bulletin-5/. ↩

-

Tanzanian elephant poaching kingpin detained in Mozambique, Club of Mozambique, 25 July 2017, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/tanzanian-elephant-poaching-kingpin-detained-in-mozambique/; Estacio Valoi, East Africa’s ivory smuggled out of Mozambican ports, Oxpeckers, 2017, https://oxpeckers.org/2017/11/ivory-smugglers/; Tanzanian elephant poaching kingpin detained in Mozambique, Club of Mozambique, 25 July 2017, http://clubofmozambique.com/news/tanzanian-elephant-poaching-kingpin-detained-in-mozambique/. ↩

-

Ivory kingpin arrested in Mozambique, WCS Newsroom, 27 July 2017, https://newsroom.wcs.org/News-Releases/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/10414/Ivory-Kingpin-Arrested-in-Mozambique.aspx. ↩

-

Estacio Valoi, East Africa’s ivory smuggled out of Mozambican ports, Oxpeckers, 2017, https://oxpeckers.org/2017/11/ivory-smugglers/. ↩

-

Mike Gaworecki, Most wanted elephant poacher and ivory trafficker in Tanzania arrested, Mongabay, 5 November 2015, https://news.mongabay.com/2015/11/most-wanted-elephant-poacher-and-ivory-trafficker-in-tanzania-arrested/ ↩

-

The most prominent among these is the acquittal of Feisal Mohamed Ali in August 2018. He had originally been convicted in July 2017 for being in possession of 2 152 kilogrammes of ivory and sentenced to 20 years in jail and a KSH 20 million fine. See On the brink of acquitting another ivory trafficker, SeeJ-AFRICA 10 April 2019, https://www.seej-africa.org/on-the-brink-of-acquitting-another-ivory-trafficker/. ↩

-

In Kenya, Abdurahman Mohammed Sheikh and his two sons were charged in 2015 with exporting over 3 tonnes of ivory to Thailand. Prosecution remains ongoing, with the latest hearings resulting in a postponement to 7 April. Nation Kenya, judge now freezes the assets of seven ivory case suspects, 26 August 2015, https://nation.africa/kenya/news/judge-now-freezes-the-assets-of-seven-ivory-case-suspects-1122864; information shared by Daniel Stiles, present at the latest hearing of Sheikh’s case. ↩

-

Tanzania Investigation and Prosecution of Wildlife and Forestry Crime, a Rapid Reference Guide for Investigators and Prosecutors, Volume 1, version 4, February 2018, developed by UNODC and the Tanzanian Director for Public Prosecutions. ↩

-

Mwinyi Jamal Kitalamba @ Igonza & Others vs Republic (Criminal Appeal No.348 of 2017) [2020] TZCA 307; (16 June 2020), https://tanzlii.org/tz/judgment/court-appeal-tanzania/2020/307-0. ↩

-

Salivius Francis Matembo & Others vs Republic (Misc. Crim Appl. No.206 of 2019) [2019] TZHC 189; (20 December 2019), https://tanzlii.org/tz/judgment/high-court-tanzania/2019/189-0. ↩