Drug pricing data: why the methodology matters.

Drug prices are some of the most widely used pieces of data about illegal drug markets. Almost any reporting and analysis on drug markets contains some estimate of the value of that particular market, and drug seizures by police are widely reported with estimates of their value.1 Price data is useful for journalists and analysts seeking to explain the drug trade and its impacts to their readers, law enforcement, and for researchers seeking to understand the drug market. It can have a real-world impact on the sentencing and prosecution of drugs offences.

However, up-to-date and publicly available data on drugs prices is scarce, and the methodologies used to collect this data also may present issues. The GI-TOC has been developing strategies to collect data on illicit economies, including drugs prices, which aim to take a different approach to improving this critical evidence base.

Drug pricing data in the courtroom

In at least three countries in East and southern Africa, the value of drugs has a direct impact on the classification of a criminal offence or on sentencing, Similar measures are also in place elsewhere, such as Slovakia and Ireland.2

In South Africa, sentencing guidelines view the value of drugs as an aggravating factor of an offence when the value of the drugs involved is more than ZAR50 000 (US$3 328), or ZAR10 000 (US$666) if the offence is committed by a criminal group.3

In Mauritius, under the Dangerous Drugs Act 2000, an offender is charged as a ‘trafficker’ when the street value of the drugs exceeds 1 million Mauritius rupees (US$24 464).4

Uganda’s Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (Control) Act 2016 likewise prescribes penalties based on drug value in possession cases. In addition to imprisonment, the act prescribes fines of UGX10 million (US$2 715) or three times the market value of the drug, whichever is greater. The act prescribes the same fine in cases of trafficking, in addition to life imprisonment.5

Interestingly, the Ugandan legislation states that the market value of the drug in question has to be certified by the proper officer of the court, and the certificate presented as a prima facie piece of evidence at trial. At least as recently as December 2019, this provision was creating problems in Uganda’s courts, particularly in cases where drugs were being trafficked through Uganda, due to debate as to whether the drug value was to be estimated for the value in Uganda itself or the destination country. The provision was also not being widely used in the courts, in part because the market value of drugs was not being properly certified for use at trial.6

Lighting up a homemade heroin pipe in Kampala, Uganda. Under Uganda’s drugs legislation, the value of the drugs seized has an impact on the penalty given in drugs possession and trafficking cases.

Photo: Michele Sibiloni

The collection of price data therefore has a very real-world implication for people convicted of possession and trafficking offences. It is therefore vital that the methodology used to create such data is reliable.

Taking a different approach to drug price data

The GI-TOC is in the process of conducting a series of price monitoring studies for illegal markets in East and southern Africa – the first of which, on heroin, has been published – as well as a wider initiative to develop domestic capacity to create and maintain a real-time heroin price index in the region.7

For these pricing studies, we have developed methodologies for collecting retail drug prices in partnership with organizations run by people who use drugs (PWUD) in the region, specifically with PWUD networks in South Africa and Tanzania.8 As far as possible, the pricing research has been conducted with and by PWUD.9

In each instance, information on drug retail prices was collected across a number of drug-selling areas. Extensive sampling was done through user interviews, in most cases conducted by other PWUD research partners. This data was then cross-referenced with similar price data collected from interviews with local dealers and drug suppliers. This approach, which aimed to bring together a high volume of data across many consumers and suppliers, aimed to involve people who participate in the drug market so as to minimize bias and create a more accurate picture of how the economics of the market work.

Figure 2 Comparison between GI-TOC heroin drug pricing data and estimates from government agencies.

NOTE: For each country listed, the estimate is for average national heroin price per gram, 2020. Currency conversions via Oanda.

SOURCE: Data shared by the South African Police Service, the Mauritius Anti-Drug and Smuggling Unit and the Agency for the Prevention of Drug Abuse and Rehabilitation.

One primary feature of this consumer-centred approach to drug pricing has been the revelation that the data collected from these studies can differ significantly from estimates collected by law enforcement. In Mauritius, the estimated average heroin price per gram shared with our research team by law enforcement was between three and four times higher than that calculated from survey data and interviews.

Similarly, in South Africa, our study published in May 2020 compared two different methods of collecting retail heroin prices.10 In the first, data was collected in partnership with a local civil society organization run by PWUD. The second method was done in collaboration with the South African Police Service (SAPS), with data collected by law enforcement personnel from informants and other sources at district-level throughout the country.11

The rough mean national price for one gram of heroin, as determined by SAPS data, was over twice that derived from PWUD data. Similarly in Madagascar, estimates of heroin prices shared in interviews with law enforcement were higher than estimates from our data collection, though the differences were less stark than in South Africa and Mauritius.

It could be argued that the differences between our PWUD-led data and police-collected data is because street-level retail drugs may be adulterated with other substances, and therefore differ in value from drugs seized by police. In the absence of purity testing, which would eliminate this possibility completely, it is unlikely on two key fronts.

First, our methodology has been developed, as far as possible, to mitigate influences on price estimates. Sampling was done extensively within and across a range of locations, through as many sources as possible, to create averages that took into account the variability in prices often seen in drug markets. This may be variability on the part of dealers, as they may change prices depending on whether the user is a trusted customer. It may be variability on the drug sample size, from a dose to gram to multiple grams. Our estimates, reviewed by users, aimed to produce an average that brings this variety into account.

Second, law enforcement estimates of drug pricing stem largely from two sources: seizure of drugs from users arrested for drug possession, and estimates derived informant users and undercover officers. There is little evidence that the personal caches of retail drugs seized by police from arrested users differ significantly in terms of purity from drugs that other users are widely purchasing and using in the same marketplace of our sampling; or that paid informants would be reporting street-based retail prices based on significantly different levels of purity.

Methadone distribution in the Seychelles. As the heroin-using population in the archipelago has exploded, authorities have implemented a large-scale methadone distribution programme.

Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP via Getty Images

However it is possible that data collection by law enforcement contains some biases. There may be, for example, an implicit bias in the filtering of drug price information through the law enforcement–informant relationship. Equally, it is possible that the political and professional structures within law enforcement institutions and their constituent drug interdiction units may lead to implicit reporting bias with respect to the price data and its place within the broader contexts that validate specific drug-based planning and action. In point of fact there are obvious political incentives for domestic law enforcement being seen to take high-value drugs off the streets, personal performance incentives for officers being seen to perform well and incentives within a policy of drug prohibition for offenders to be given the highest possible penalties, which may be predicated on the value of the drugs involved.

It is notable that the only instance found where official sources produced a lower price estimate than our data collection was in the Seychelles, where information on estimated drug prices was shared with us by the Agency for Prevention of Drug Abuse and Rehabilitation (APDAR). This is perhaps explained by the fact that APDAR is not a law enforcement agency, but works on drug-related public health. The agency conducts peer-to-peer outreach with a network of PWUD with whom they collaborate, and conduct studies estimating the size of the PWUD population with methods that include this network. As such, APDAR’s data differs from information collected by law enforcement personnel from informants.

Other uses and implications of drug price data

The possibility of bias in drug pricing data being used in prosecutions and sentencing is a cause for concern. Up-to-date, reliable pricing data also is useful in other ways. From a research perspective, drug prices are a useful metric in studying the characteristics of drug markets.12

When compared over time, drug prices can provide insight into the stability (or instability) of a drug market. For example, GI-TOC research in the Seychelles reported that heroin prices have dropped sharply since 2018. This suggests there has been a significant shift in the market, an insight that provided an avenue for our research to investigate. While some interviewees attributed the fall to the introduction of a widespread methadone programme in the Seychelles, the drop in price may also be linked to other factors, and may suggest that new lines of supply have opened up and flooded the market. 13

Drug prices can also give an insight into different drug supply chains and routes. Our research in Tanzania found that heroin was widely available, often at the same price for significantly different levels of purity to the same retail customers. This is a symptom of a domestic heroin market with several different routes of supply and different networks involved, and suggests there are few barriers to entry for aspiring traffickers and dealers.14

Drug prices can also be important metrics in examining the impact of drug policy and law enforcement actions. For example, in locales where police are aiming to disrupt the market, ascertaining whether prices fluctuate in response to interdiction operations can indicate whether the operation has had an impact.

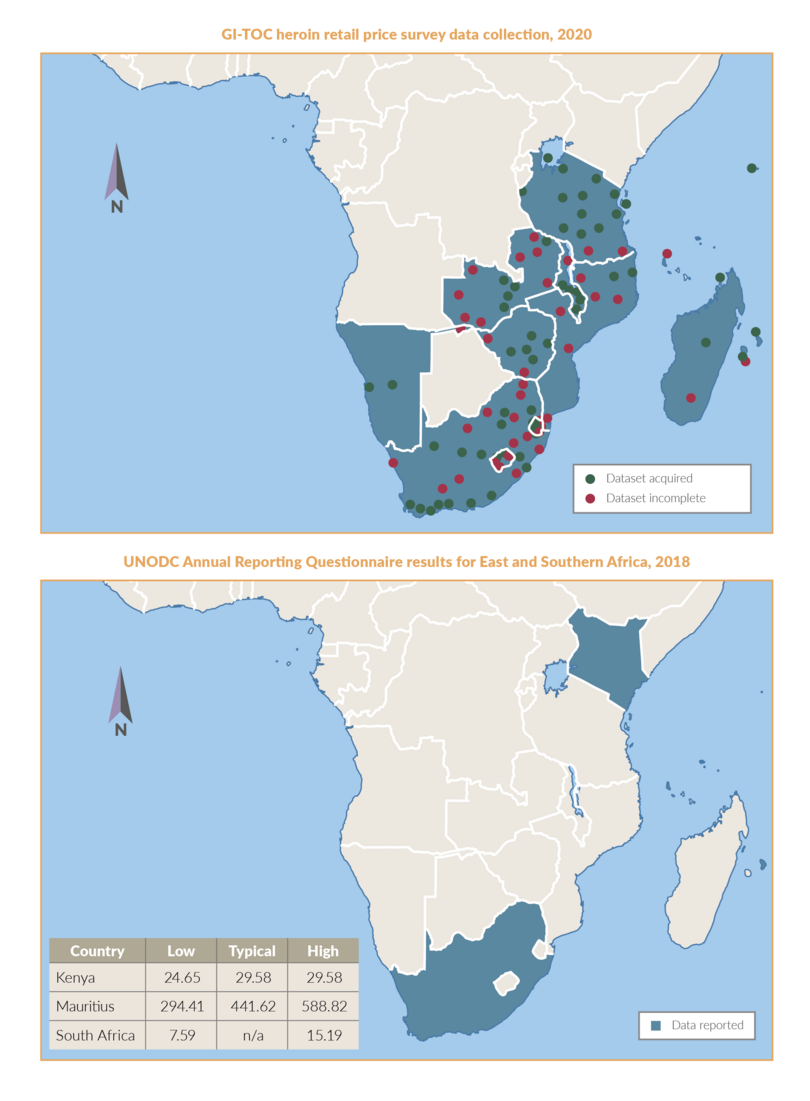

Important as this may be, up-to-date and publicly available information on drug prices is scarce. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) attempts to collect price data from member states in its annual reporting questionnaire, but completion rates are low. As shown in Figure 3, the only states in East and southern Africa that reported heroin price data for 2018 (the most recent year for which the data is currently available) are Kenya, South Africa and Mauritius.15 The data collection process also presents issues, as the UNODC receives data from member states with no independent verification. As we have highlighted, data collected by law enforcement may be subject to bias, which then is replicated in the UNODC data.

The inclusion of PWUD in the design and collection of data on drug markets is a political question, as well as a question of good research design and the elimination of bias. For years, civil society organizations and advocacy groups of PWUD have argued that drug-related policy should be created with PWUD having meaningful involvement and a voice. In its report ‘Don’t treat us as outsiders’, the Aids and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa draws together the input of PWUD groups in southern Africa to analyze the dehumanizing impact and stigma that PWUD experience as a direct result of drug policy.16 Therefore developing strategies such as drug pricing surveys that include meaningful involvement of PWUD is one small step towards more inclusive and less stigmatizing drug policy, as well as a step towards creating more reliable, up-to-date datasets for a type of data that has wide real-world impacts.

Figure 3 Retail heroin pricing data in East and southern Africa, showing results for per-gram heroin price, UNODC and GI-TOC.

NOTE: UNODC gather data on drug prices through its Annual Reporting Questionnaire. The above map and table illustrate the full data available on retail heroin pricing in East and southern Africa for the latest year available, 2018, in USD. Throughout 2020, the GI-TOC have also been developing methods of data collection on retail drug pricing with PWUD-run civil society groups. The first map highlights the countries and locations where this data collection has taken place.

SOURCE: UNODC

Notes

-

See Frontier Myanmar, Southeast Asia’s meth gangs making $60 billion a year: UN, 19 July 2019, https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/southeast-asias-meth-gangs-making-60-billion-a-year-un/; Dame Carol Black, Independent report, Review of drugs: phase one report, for the UK Home Office, February 2020, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-drugs-phase-one-report. ↩

-

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Penalties for drug law offences in Europe at a glance, accessed 17 February 2021, https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/topic-overviews/content/drug-law-penalties-at-a-glance_en. ↩

-

Republic of South Africa, Criminal Law Amendment Act 1997, schedule 2, part II; http://www.saflii.org/za/legis/num_act/claa1997205.pdf. Currency conversion via Oanda to US dollar value as of 2 March 2021. The same conversion has been used for subsequent US dollar values for monetary limits in legislation. ↩

-

Mauritius, Dangerous Drugs Act 2000 (subsequently amended in 2003 and 2008), http://www.fiumauritius.org/English/AML%20CFT%20Framework/Documents/Dangerous_Drug_Act_2000_upd.pdf. See also Library of Congress, Sentencing Guidelines, South Africa, https://www.loc.gov/law/help/sentencing-guidelines/southafrica.php. ↩

-

Uganda, The Narcotic Drugs And Psychotropic Substances (Control) Act, 3, 2016, https://www.fia.go.ug/sites/default/files/2020-06/The%20Narcotic%20Drugs%20and%20Psychotropic%20substances%20%28Control%29%20Act%202016.pdf. ↩

-

Interviews with law enforcement and lawyers in Uganda, December 2019. ↩

-

See Jason Eligh, A Shallow Flood: The diffusion of heroin in Eastern and Southern Africa, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, May 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/heroin-east-southern-africa/. This index would ideally would exist in an open source format with input from PWUD networks and civil society and law enforcement partners. ↩

-

See Jason Eligh, A Shallow Flood: The diffusion of heroin in Eastern and Southern Africa, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, May 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/heroin-east-southern-africa/ ↩

-

Lucia Bird and Julia Stanyard, The Political Economy of Drug Trafficking Markets in the Indian Ocean, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, forthcoming, 2021. ↩

-

See Jason Eligh, A Shallow Flood: The diffusion of heroin in Eastern and Southern Africa, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, May 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/heroin-east-southern-africa/. ↩

-

This is part of a programme of cooperation between the GI-TOC and SAPS for the purpose of building and maintaining a national drug-price monitoring database for the country. ↩

-

See Jason Eligh, A Shallow Flood: The diffusion of heroin in Eastern and Southern Africa, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, May 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/heroin-east-southern-africa/ and J Caulkins, Domestic geographic variation in illicit drug prices, Journal of Urban Economics, 37, 1995, 38–56. ↩

-

Lucia Bird and Julia Stanyard, The Political Economy of Drug Trafficking Markets in the Indian Ocean, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, forthcoming, 2021. ↩

-

See Jason Eligh, A Shallow Flood: The diffusion of heroin in Eastern and Southern Africa, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, May 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/heroin-east-southern-africa/. ↩

-

UN Office in Drugs and Crime, Retail drug price and purity level, https://dataunodc.un.org/data/drugs/Retail%20drug%20price%20and%20purity%20level. ↩

-

Aids and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa, ‘Don’t treat us as outsiders’: drug policy and the lived experiences of people who use drugs in Southern Africa, 2019, https://www.arasa.info/media/arasa/Resources/research%20reports/don-ttreatusasoutsidersfinal.pdf. ↩