Is Afghanistan a new source for methamphetamine in eastern and southern Africa?

Though famed for its role at the heart of the global heroin trade, recent years have seen a huge increase in the production of methamphetamine in the mountains of Afghanistan. In a few short years, meth production in Afghanistan has grown to the extent that it may be supplying markets as far afield as South Africa and Australia.

Until recently, neighbouring Iran was home to the most mature regional market for the production and consumption of methamphetamine. Use of meth alongside heroin has become increasingly common in Iran over the past decade.1 However, as research from David Mansfield and Alex Soderholm of the London School of Economics has brought to light, increased law-enforcement pressure and regulation of precursor chemicals in Iran has curtailed large-scale meth production in the country.2 Meth producers from Iran appear to have maintained a level of production by passing on the skills and knowledge for meth manufacture to counterparts in Afghanistan.3 This was a natural development as the necessary precursor chemicals – such as ephedrine – are now more widely available in Afghanistan.

At the same time, the area of Afghanistan under opium-poppy cultivation dropped sharply in 2018 and the estimated opium production fell by 29% on the previous year.4 These decreases, in particular in the northern and western regions, were attributed mainly to the impact of a severe drought. For opium-poppy farmers reliant on the crop as a significant contributor to their agricultural livelihoods, the new methods of producing methamphetamine became a lucrative alternative. As a result, an abundance of artisanal ‘meth labs’ quickly emerged in these regions, large swathes of which previously had been dominated only by opium.

Yet the real breakthrough came when it became known that the ephedra plant – a common shrub known locally as oman that grows abundantly across northern and central Afghanistan – contained a naturally occurring form of ephedrine, one of the key precursor chemicals required to produce crystal methamphetamine.5 Ephedra has therefore become a game-changer for Afghan meth production as it provided a secure domestic supply of the necessary precursor and significantly shortened the production supply chain, therefore substantially lowering overall manufacturing costs.6 As a result, Afghanistan has seen a surge in meth production, distribution and use.7

In response to this sudden emergence of widespread meth production in Afghanistan, the United States (under the banner of the International Security Assistance Force) embarked on a bombing campaign in May 2019. The intention of this initiative was to destroy many of the so-called ‘meth labs’ which had spread throughout the poppy-growing region of the country and, unlike opium (an agricultural product), could remain an active, year-round security threat.8 The campaign was justified on the grounds that it aimed to deny a new revenue stream to the Taliban by preventing them from taxing these new drug-production facilities and their flows. However, this drew criticism from observers, who argued that the meth labs were not lawful military targets (and could in any case be reconstructed with relative ease )9 and that the estimated revenue denied to the Taliban had been vastly overstated. Opposition to the strikes also mounted after it was revealed that they had resulted in the deaths of at least 30 civilians.10

Low-purity crystal methamphetamine, worth less than US$3, photographed in Afghanistan.

© Kern Hendricks

Markets for Afghan meth

Still from a video purportedly showing heroin being packaged on the Pakistan– Afghanistan border. The heroin is scooped from the central pile (middle right) into one-kilo bags (such as that placed on the scale in the centre). Similar packaging and drug texture were subsequently seen in a sample of heroin by GI-TOC researchers in Durban.

SOURCE: GI-TOC

An extraordinary volume of methamphetamine is now being produced in Afghanistan, supplanting the dominance of opium, which has long been the country’s primary illegal narcotic.11 One of the major unanswered questions about this nascent meth production however surrounds the consumption markets for the drug.12 Though domestic meth use has reportedly risen sharply in Afghanistan, and Iran and Pakistan do provide neighbouring consumption markets that may absorb some portion of this new production, it is estimated that the volume currently produced in Afghanistan far outstrips the totality of this domestic and neighbouring demand. The bulk of this production must be destined for markets further afield, but the question is: where?

Ongoing research by the GI-TOC appears to shed some light on this issue. As we know, heroin is bulk-produced from Afghan opium and packaged in Pakistan before being shipped by dhow along the so-called ‘southern route,’ departing from ports along the Makran coast of Pakistan en route to African and European markets. There is emerging evidence to suggest that Afghan meth shipments are being ‘piggybacked’ with this heroin along the pre-existing routes used for international distribution.

International naval forces operating as part of the Combined Task Force 150 (CTF 150) have reported a significant increase in meth seizures in their area of operations in 2019 (which encompasses a wide swathe of the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Aden).13 As of late December 2019, the force had seized 257 kilograms of meth – including one seizure in the Arabian Sea from a dhow carrying 94 kilograms of heroin and 76 kilograms of crystal meth in October 2019 – compared to only 9 kilograms of meth seized in 2018.14

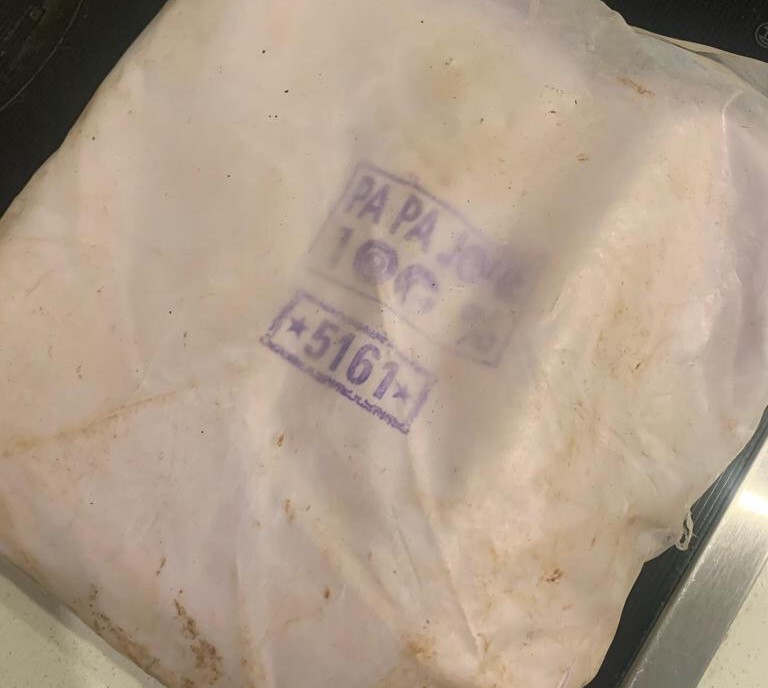

1) A one-kilogram bag of heroin offered for sale in Durban, August 2020, showing the distinctive stamps also seen on samples seized elsewhere, which appear to be shipments of Afghan heroin packaged in Pakistan. 2) The interior of the same bag of heroin shown (left). The consistency and packaging is consistent with the heroin being processed in the footage reportedly from Peshawar, Pakistan.

SOURCE: GI-TOC

Figure 3 Trafficking routes of methamphetamine from Afghanistan to southern Africa.

Men smoke crystal methamphetamine in Fayzabad, in the northern province of Badakhshan.

© Kern Hendricks

Heroin seized from a truck crossing into South Africa from Mozambique at the Komatipoort border point in May 2020.

© South African Police Service

A shard of crystal meth – not visually dissimilar from samples pictured in Afghanistan – for sale in Cape Town and confirmed by local distributors to originate from a new ‘South Asian’ supply channel that first appeared in South Africa in late 2019.

SOURCE: GI-TOC

Similarities found between different seizures appear to suggest an interlinked supply chain for meth and heroin. In December 2019, a Pakistani-crewed dhow was intercepted off the coast of Pemba, Mozambique, carrying a mixed cargo of both heroin and 299 kilograms of methamphetamine.15 Pemba is known to be a major port of entry on the East African coast for dhows – predominantly from the coast of Iran and Pakistan – carrying heroin, yet this mixed shipment of meth was the first of its kind in Mozambique. Several months later, in May 2020, a cargo truck was intercepted by the South African Police Service attempting to cross the Mozambican border into South Africa at the Komatipoort border post while carrying a large shipment of heroin and methamphetamine.16

Elsewhere, Sri Lankan naval forces intercepted two trawlers in international waters carrying 400 kilograms of heroin and 100 kilograms of crystal methamphetamine in February 2020 – Sri Lanka’s biggest-ever drug bust at sea.17 Eight Pakistani nationals were detained in the operation, and investigations suggested the boats came from Pakistan’s Makran coast, with the drugs presumed to have originated in Afghanistan. The vessel was allegedly headed to a transit stop in Penang, Malaysia, for onward transfer of the cargo to Australia, where meth prices are very high.

Heroin and methamphetamine seized by the Sri Lankan Navy from two Pakistani fishing trawlers in February 2020. The heroin bricks, on the left, share numerous characteristics with the heroin seized in Durban.

© Sri Lankan Navy

A Pakistani-crewed dhow was seized by Mozambican authorities off the coast of Pemba, Mozambique, in December 2019, carrying methamphetamine and heroin.

© National Criminal Investigation Service (SERNIC)

In July 2020, a GI-TOC research team took images of a heroin shipment that had just been delivered in Durban, South Africa. Similar images were taken of a joint heroin and meth shipment that had arrived in Cape Town, South Africa. Each of these shipments were in the process of being unbundled in advance of their contents’ preparation for the local retail market. Wrapped in thick whitish plastic bags of one-kilo denominations, the packaging was stamped with distinctive blue markings reading ‘Pa Pa Jone 100%’ and ‘5161’. These markings are consistent across each of the dual-commodity seizures mentioned above: the drugs seized from the dhow in Mozambique in 2019, those seized at the Komatipoort border crossing and those seized by the Sri Lankan Navy, suggesting a common origin for these shipments.

Interviews by GI-TOC researchers with local meth users and distributors in Cape Town in August 2020 saw informants from both groups confirm that a new source of meth had entered the South African market ‘in the past eight to ten months’.18 Described by both groups as ‘Pakistani meth,’ this new supply appears to be provided through local South Asian syndicates based in South Africa and Mozambique, connecting with suppliers in Pakistan. The purity of this new supply of ‘Pakistani meth’ is seen by South African users as being quite high, ‘just as good’ as the Mexican-produced crystal meth arriving from Nigeria and better than the Chinese-produced meth that is manufactured in locations around Johannesburg.

Altogether, this combination of factors may help us towards understanding where Afghanistan-produced meth is ultimately headed. Pre-existing infrastructure and flow channels along traditional heroin routes – the dhow crews involved in trafficking, the ports whereby shipments can be landed without detection and the connections to distributors in southern Africa – have enabled this supply chain to emerge, while recent seizures provide strong circumstantial evidence that suggests Afghan meth is transiting Mozambique and has now become an emergent commodity option in the growing South African meth market. New high-quality crystal meth flows which seem to be appearing recently in Malawi, Tanzania and Kenya may suggest this new development is also a regional phenomenon.

Notes

-

David Mansfield and Alex Soderholm, Long Read: The unknown unknowns of Afghanistan’s new wave of methamphetamine production, LSE US Centre, 30 September 2019, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2019/09/30/long-read-the-unknown-unknowns-of-afghanistans-new-wave-of-methamphetamine-production/. ↩

-

David Mansfield and Alex Soderholm, New US airstrikes obscure a dramatic development in the Afghan drugs industry – the proliferation of low cost methamphetamine, LSE US Centre, 28 May 2019, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2019/05/28/new-us-airstrikes-obscure-a-dramatic-development-in-the-afghan-drugs-industry-the-proliferation-of-low-cost-methamphetamine/. ↩

-

Ali M Latifi and Morteza Pajhwok-Karimi, How narcos brought meth labs to Afghanistan, TRT World, 17 December 2018, https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/how-narcos-brought-meth-labs-to-afghanistan-22562. ↩

-

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Sharp drops in opium poppy cultivation, price of dry opium in Afghanistan, latest UNODC survey reveals, 19 November 2018, https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2018/November/sharp-drops-in-opium-poppy-cultivation–price-of-dry-opium-in-afghanistan–latest-unodc-survey-reveals.html. ↩

-

Afghan drug barons are branching out into methamphetamines, Economist, 5 September 2019, https://www.economist.com/asia/2019/09/05/afghan-drug-barons-are-branching-out-into-methamphetamines. ↩

-

Kern Hendricks, The wild shrub at the root of the Afghan meth epidemic, Undark, 20 May 2020, https://undark.org/2020/05/20/afghanistan-meth-ephedra/. ↩

-

UN News, Synthetic drugs are making headway in Afghanistan, 14 February 2017, https://news.un.org/en/story/2017/02/551452-synthetic-drugs-are-making-headway-afghanistan-un-agency-reports. ↩

-

BBC News, US meth lab strikes in Afghanistan killed at least 30 civilians, says UN, 9 October 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-49984804; David Mansfield and Alex Soderholm, New US airstrikes obscure a dramatic development in the Afghan drugs industry – the proliferation of low cost methamphetamine, LSE US Centre, 28 May 2019, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2019/05/28/new-us-airstrikes-obscure-a-dramatic-development-in-the-afghan-drugs-industry-the-proliferation-of-low-cost-methamphetamine/. ↩

-

David Mansfield, Despite claims to the contrary, US air raids against Afghanistan’s drugs labs have had little to no impact, LSE US Centre, 25 April 2019, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2019/04/25/despite-claims-to-the-contrary-us-air-raids-against-afghanistans-drugs-labs-have-had-little-to-no-impact/. ↩

-

Ibid; see also BBC News, US meth lab strikes in Afghanistan killed at least 30 civilians, says UN, 9 October 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-49984804. ↩

-

UN World Drug Report: Meth market grows while opiate production same in Afghanistan, Reporterly, 25 June 2020, http://reporterly.net/latest-stories/un-world-drug-report-meth-market-grows-while-opiate-production-same-in-afghanistan/. ↩

-

David Mansfield and Alex Soderholm, Long Read: The unknown unknowns of Afghanistan’s new wave of methamphetamine production, LSE US Centre, 30 September 2019, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2019/09/30/long-read-the-unknown-unknowns-of-afghanistans-new-wave-of-methamphetamine-production/. ↩

-

Brett Sampson, Combined Maritime Forces: Update, May 2017, https://www.ukmto.org/-/media/ukmto/mievom-notes-pdf/indian-ocean/2017/may/cmf-presentation.pdf. ↩

-

HMS Defender seizes record haul of crystal meth, Combined Maritime Forces, 23 December 2019, https://combinedmaritimeforces.com/2019/12/23/hms-defender-seizes-record-haul-of-crystal-meth/. Ministry of Defence, $1m drug bust in the Arabian sea: HMS Montrose, Medium, 14 October 2019, https://medium.com/voices-of-the-armed-forces/1m-drug-bust-in-the-arabian-sea-hms-montrose-726e1dceb753. ↩

-

Joseph Hanlon, Speculation: Are the heroin routes shifting?, Club of Mozambique, 10 March 2020, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/speculation-are-the-heroin-routes-shifting-by-joseph-hanlon-154706/. ↩

-

Ntwaagae Seleka, 2 arrested for trying to smuggle drugs worth R10 million into SA from Mozambique, News24, 25 May 2020, https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/2-arrested-for-trying-to-smuggle-drugs-worth-r10-million-into-sa-from-mozambique-20200525. ↩

-

Devesh K. Pandey, Seizure of Afghan meth on high seas triggers concern, The Hindu, 22 March 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/seizure-of-afghan-meth-on-high-seas-triggers-concern/article31136531.ece; Devesh K. Pandey, Haul points to Pak-based cartels’ role in drug trafficking via sea routes, The Hindu, 2 April 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/haul-points-to-pak-based-cartels-role-in-drug-trafficking-via-sea-routes/article31237497.ece. ↩

-

Information acquired from interviews undertaken in Cape Town, August 2020. ↩