The fight against illegal gold mining in South Africa faces new (and old) challenges.

Illegal gold mining has been on the rise for the past decade in South Africa. Worsening ore grades, rising costs (as shafts have been sunk ever deeper), bouts of labour and social unrest and falling investment in new mines have all contributed to a sharp decline in the gold mining sector. Widespread layoffs saw the number of workers in the industry fall from 190 000 in 2018 to just 95 000 in 2019.1

As large mining operations have shuttered, the abandoned shafts have become ready targets for growing numbers of illegal miners. Commonly referred to as ‘zama zamas’ – a Zulu term that roughly translates as ‘take a chance’ – many are from neighbouring countries such as Lesotho, eSwatini, Mozambique and Zimbabwe who have often previously worked in the mines.

Zama zamas will often spend months underground without surfacing and depend heavily on outside support for food and other necessities. It is arduous and dangerous work. Some carry pistols, shotguns and semi-automatic weapons to protect themselves from rival gangs of miners.2

‘The length of time they spend underground depends on the depth of the mine and access to it,’ explained Lyle Pienaar, an executive for risk and security at Pan African Resources, a mid-tier gold producer. He continued:

We had one guy who told us when he came up that he had been underground for up to 18 months. In deeper mines, they spend months underground, tapping into the mine’s electricity supply. And they’ll take everything down with them: food, booze, fridges, little DVD players, mining drills, phendukas [crushers]. Biltong [a dried cured meat] is hugely popular. It is almost a staple food. Often it is boiled with water to make a soup. I know of a number of butchers near mines that sell thousands of dollars’ worth of the stuff every month.3 In some cases, there is literally an underground economy where gold is sold to corrupt mining staff who then take it up and smuggle it out above ground. Conversely, money is smuggled back down.

Photographs of the illegal miners arrested taken as they emerge from the mines attest to the physical effects of spending months underground, manifested in a ghostly pallor around the eyes.

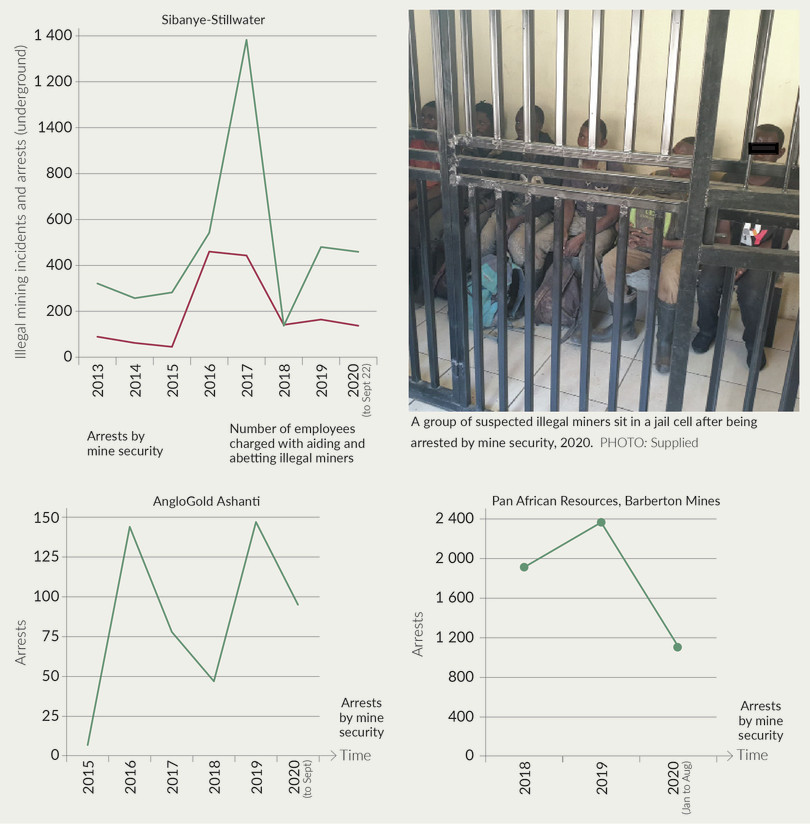

In 2017, Sibanye-Stillwater (Sibanye), one of South Africa’s largest gold producers, began attempting to clear illegal miners from its mines through its operation named Zero Zama,4 resulting in 1 400 arrests carried out by mine security. By Sibanye’s own assessment, a decrease in arrests the following year testified to the success of this operation.5

A group of suspected illegal miners armed with firearms. There are reportedly violent clashes between illegal mining groups which have resulted in four deaths in 2020.

PHOTO: Supplied

Figure 2 These graphs represent data shared by three mining companies in South Africa: Sibanye-Stillwater and AngloGold Ashanti are two of the largest gold mining operators in South Africa, while Pan African Resources is a mid-tier mining company. While these do not represent the entirety of illegal activity in the gold mining sector in South Africa, collectively the data demonstrates the scale of the issue.

However, in late 2018, Sibanye’s gold operations were hit hard by a strike by the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union. The strike, which lasted for five months until April 2019, also saw violence erupt between rival miners’ unions.6 The halt in operations provided an opportunity for illegal miners. ‘The 2018 strike caused a bit of a setback to us. The illegal miners took the gap to start going back underground which put us on the back foot,’ said Nash Lutchman, head of protection services at Sibanye.7

Corruption and collusion

The challenge to tackling illegal mining goes beyond labour disputes. Over the past decade, criminal networks involved in illegal mining have exploited the decline in the state’s law-enforcement capacity and rise in corruption that largely took place during the tenure of former President Jacob Zuma to grow in sophistication and influence.

‘What happened during the Zuma years was that there was a systematic disempowering and dismantling of state organs such as the National Prosecuting Authority and eroding expertise in serious economic offences and metals-related offences, which gave the syndicates the wind in their sails,’ says Lutchman. ‘They have always been sophisticated and what the Zuma years did was make them better. This is a big driver behind illegal mining activity.’

To fill the void left by police, mining companies have had to establish their own parallel investigative capacity. ‘We can’t go to the local police station near a mine with information about syndicate activity because of corruption,’ says Pienaar. He continues:

The police have warned us about this themselves. Instead, we have handed over a lot of information to the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation, Crime Intelligence, Provincial and National police structures. But nothing ever transpires and you can literally see the syndicates getting bigger and bigger and starting to legitimize themselves, laundering money into lodges, taxi businesses, liquor stores and guest houses.

At one of our mines we have arrested more than 4 000 illegal miners in the last two years. We account for about 85% of the crime statistics at that police station. But not a single detective or police vehicle has been assigned to deal with this. We have to gather the evidence, we write the police docket, and make a copy in case it goes missing, we have to transport the people we have arrested to the police station because the police won’t come and fetch them. Then we have to track the dockets and the prosecution.

Three suspected illegal miners equipped with flashlights in a mineshaft, 2020.

PHOTO: Supplied

Suspected illegal miners attempt to access a blocked-off area of a mineshaft deep underground. South Africa has some of the deepest gold mines in the world, some reaching over 3 kilometres deep. Even at this level, mine security have installed surveillance cameras to monitor illegal activity.

PHOTO: Supplied

Police data for illegal mining offences is not available because there is no specific law forbidding the activity, according to Louis Nel, a security consultant and analyst. People can be charged for illegal possession of gold-bearing material, but according to Nel, this route is seldom taken as it requires lab work which can take months or even years. Typically, those involved in illegal mining are charged with trespassing or immigration offences.8

‘The criminal justice system treats it as a misdemeanor,’ says Pienaar. ‘Even if they are caught with tools, generators, mining equipment going down into a mine, it is trespassing. These cases are not treated as organized crime cases and they should be. These are people who are part of a syndicate.’ Reportedly, those in control of the syndicates pay for legal representation for miners who are arrested, suggesting that illegal mining is highly organized.

Corruption within the mining industry has also had a damaging effect on efforts to root out illegal miners and, in some ways, poses a much bigger long-term threat. Sibanye’s data shows that the number of its employees or contractors charged with aiding and abetting illegal miners rose from 141 in 2018 to 184 last year.9 So far this year, 137 of the company’s staff have been arrested.10

Communities rally to support the zama zamas

Aside from the lack of effective policing and prevalence of rampant corruption, Pienaar argues that the criminal economy created by illegal mining has become deeply entrenched in communities around mines, and as a result, the ‘neighbourhoods that depend on the illegal mining economy will support it 100 per cent’.

This was demonstrated when in 2017 Sibanye attempted to cut off supplies to illegal miners underground and force them to the surface at its Cooke operation, 50 kilometres west of Johannesburg. The company arrested several employees suspected of collusion with the zama zamas and began providing meals for its employees before and after shifts, thereby preventing them from smuggling food down to the illegal miners. ‘The fact that we restricted supplies of food initially really throttled the illegal mining activities,’ says Lutchman.

But Sibanye’s efforts triggered a strike among its employees and an angry community response. ‘It related to the kind of investment the illegal mining syndicates were doing in the communities around the Cooke operation,’ Lutchman said. ‘They were providing food parcels, they were stocking libraries, stocking clinics, removing waste and providing water tanks. They were seen as bringing benefits to the community. They were seen to be delivering services whereas the government wasn’t.’

Mining under and after lockdown

The ‘hard lockdown’ imposed by the South African government from 27 March 2020 brought mining operations to an abrupt halt across the country, but they were gradually allowed to restart in May as South Africa relaxed its restrictions.

Sources with links to zama zamas in Free State province described the lockdown as a double-edged sword for the illegal miners. While the shutdown allowed them to continue mining relatively undisturbed, it also deprived them of vital sources of support from corrupt mine employees above ground. Without an ability to communicate with the surface, many zama zamas would have been oblivious to the pandemic raging on the surface until they were literally starved out of the mines. ‘Some of the guys who were underground were forced to come out because they could not get their supplies. This happened at Harmony and Sibanye mines in the Free State,’ a mining industry source said.11

However, global gold prices have soared during the pandemic – topping US$2 000 an ounce for the first time – as traders look for secure investment options amid economic uncertainty precipitated by the pandemic.12 There are concerns that syndicates are on a recruiting drive to send more illegal miners underground. According to Sibanye’s Lutchman: ‘We just thwarted an attempt the other day [16 September] at Driefontein mine where they tried to get 15 or 18 Zamas underground. There are greater numbers, they are more brazen, so what we are thinking is that the prices at the moment mean the syndicates are trying to get more people underground to get more product on the market.’

Analysts generally expect gold prices to remain robust for the rest of the year and beyond, so the profit incentive is likely to remain strong at a time when South Africa’s unemployment rate is widely believed to have soared to over 40% because of pandemic-triggered economic contraction. ‘We prevent an attempt this week, and next week they try again,’ said Lutchman.

Should South Africa witness a surge in illegal mining, the heady mixture of community support, closed, dormant and vacated mine shafts, corruption and lack of state capacity and political will to act on illegal mining will make it difficult for the gold sector to roll back the tide.

A group of illegal miners on-site after being arrested by mine security, 2020.

PHOTO: Supplied

Simple equipment for processing gold ore. The cylindrical pieces of equipment are known as phendukas, which along with the ball bearings (pictured in the bucket), are used to break up the rock before processing and extracting the gold.

PHOTO: Supplied

Notes

-

Minerals Council South Africa, Facts and Figures 2019 pocketbook, p 22, https://www.mineralscouncil.org.za/industry-news/publications/facts-and-figures; Ed Stoddard, South Africa’s east platinum belt hit by over 400 social unrest incidents since 2016, Reuters, 10 April 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-safrica-mining-unrest/south-africas-east-platinum-belt-hit-by-over-400-social-unrest-incidents-since-2016-idUSKBN1HH20R; Statistics South Africa, http://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=1854&PPN=P0441&SCH=7804. ↩

-

Tankiso Makhetha, Ten people arrested in connection with zama zama killings, Sowetan Live, 12 February 2020, https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/south-africa/2020-02-12-ten-people-arrested-in-connection-with-zama-zama-killings/. ↩

-

Interview with Lyle Pienaar, Johannesburg, 23 September 2020. ↩

-

Ed Stoddard, Sibanye says clears most illegal miners from gold shafts, Reuters, 26 February 2018, https://fr.reuters.com/article/us-sibanye-illegalminers-exclusive-idUSKCN1GA0I2. ↩

-

Email correspondence with Sibanye-Stillwater, 22 September 2020. ↩

-

Tim Cohen, Five-month strike at Sibanye-Stillwater gold mines has ended after Amcu decided to cut its losses, Daily Maverick, 17 April 2019, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-04-17-five-month-strike-at-sibanye-stillwater-gold-mines-has-ended-after-amcu-decided-to-cut-its-losses/. ↩

-

Interview with Nash Lutchman, head of security, Sibanye-Stillwater, 18 September 2020, via Zoom. ↩

-

Interview with Louis Nel, security consultant, Johannesburg, 21 September 2020. ↩

-

Data provided by Sibanye-Stillwater, 22 September 2020. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with a source in the mining industry, September 14 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Gold price rises above $2,000 for first time, BBC News, 5 August 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-53660052. ↩