Kidnappings continue to shake the business community in Mozambique

On 13 July 2020, businessman Álvaro Massinga, speaking on behalf of Mozambique’s main private business organization, told a press conference that ‘cases of kidnapping and abductions of businesspeople in our country are multiplying, which makes us think that the world of organized crime has directed its barbarous actions towards the business class’.1

Massinga’s statement was in response to the shooting of Agostinho Vuma – a prominent businessman, ruling party MP and president of the business association – in broad daylight in the capital Maputo, two days previously.2 Vuma was seriously injured in the attack. As Massinga’s response shows, the business community in Mozambique has both condemned Vuma’s shooting and seen it as part of a pattern, whereby businesspeople have become the targets of criminal groups in Mozambique, and the primary target for kidnappings. Few also expect the perpetrators to be brought to justice: Maputo, as one Mozambican commentator said on social media on the same day as Massinga’s statement, ‘remains the capital of impunity’.3

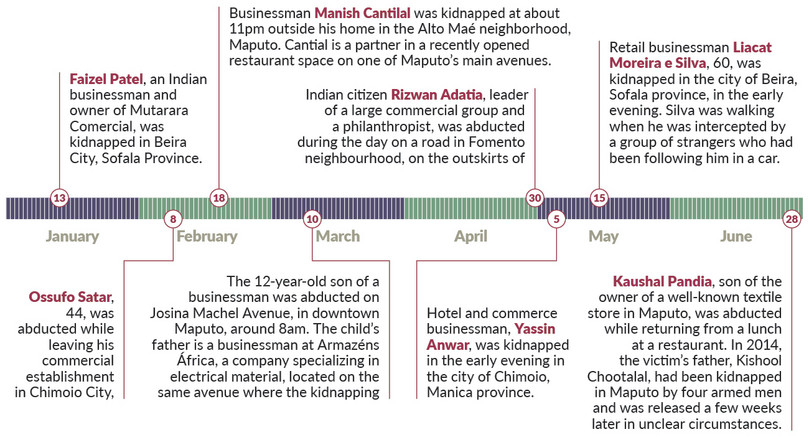

While statistics presented to the Mozambican parliament suggest that the national rate of kidnappings has in fact not so far increased in 2020,4 Massinga’s assertion that the business community is being targeted appears to be correct: the eight kidnappings that occurred in the first half of 2020 all involved prominent businesspeople or their family members.5 Since 2015, the government has repeatedly promised to bring the situation under control, but to little effect. The kidnapping phenomenon therefore looks set to continue in Mozambique.

Kidnappings in Mozambique

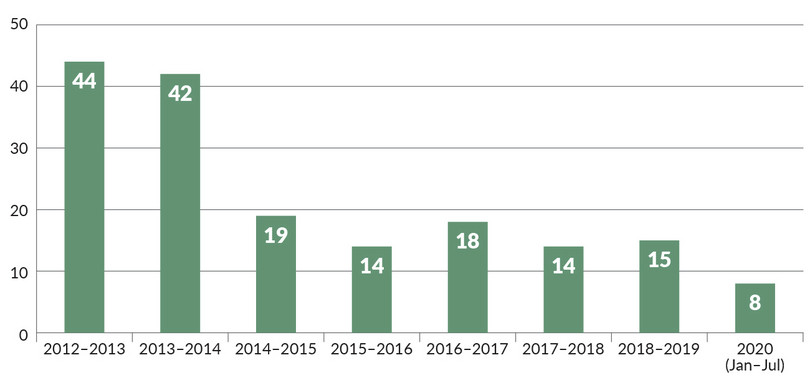

The first case of kidnapping for ransom in Mozambique was registered in 2008. A 55-year-old Dutch woman was held captive for 18 hours before her husband paid a US$20 000 ransom, negotiated down from US$100 000.6 After that time, the number of kidnappings grew steadily, from six attacks in 2011 to 17 in 2012 and 37 in 2013, according to official statistics.7 Kidnapping also spread geographically, starting in the cities of Maputo and Matola (which continue to be the main focus for kidnappers), before reaching other major Mozambican cities such as Beira, Chimoio and Nampula. Following the peak in 2013 and 2014, rates of kidnappings have since declined, ranging between 14 and 19 per year between 2015 and 2020 (measured from April to April each year, as visualized in Figure 5, below).8 While the figures do give an indication of prevailing trends, it is worth noting that many kidnappings may also go unreported to police.

Figure 4 Kidnappings of businesspeople in Mozambique, January to July 2020.

Source: Media reports.

The victims are typically abducted in daylight by armed and masked men driving vehicles without licence plates. The blindfolded victims are subsequently transferred to houses, typically in suburban areas, while the kidnappers negotiate the ransom. There have been instances of kidnappers torturing or threatening to torture their victim to encourage the immediate payment of ransoms. This was reported in the case of Manish Cantilal, who was rescued by police on 20 May 2020.9

In earlier years, the attackers communicated with victims’ relatives either through SMS texts or phone calls. The Attorney General’s Office accordingly told parliament in 2017 that the communications regulator should start enforcing the mandatory registration of SIM cards by mobile-phone companies.10 The law, which was passed in 2015, obligates users to register their ID when buying a SIM card. However, encrypted-messaging platforms such as WhatsApp, Signal or Telegram have made it difficult for the authorities to link kidnappers to particular phones.

Typically, kidnappings in Mozambique have targeted wealthy businesspeople or their family members. People who ‘show ostentatious signs of wealth, such as luxury cars, gold rings or top brand pens’ can become targets, according to Rodrigo Rocha, a lawyer and legal- and political-affairs analyst.11 Kidnappers have disproportionally targeted the Asian community, ‘as there is a perception that this community owns a lot of businesses and a lot of wealth revolves within it,’ said Maputo-based journalist and businessman Fernando Lima. There is a perception that the Asian community is ‘closed’, and that they live well due to their wealth. This view is shared even among educated people and those with senior positions in government, a businessman based in Maputo, who wished to remain anonymous, told the GI-TOC.12

Ransoms are negotiated according to the kidnappers’ estimate of what the victim’s family is able to pay, with the kidnappers sometimes gleaning inside knowledge through connections with the victim’s bank. Adriano Nuvunga, a professor and head of the Mozambican think tank Centre for Democracy and Development, says that ‘there are signs that bank workers give information about the victims’ balances and movements to kidnapping planners’.13

The ransoms demanded can be substantial, as shown by the case of businessman Rizwan Adatia, who was rescued by police on 20 May 2020. Benjamina Chaves, the director of National Criminal Investigation Service (SERNIC) in Maputo province, told the press that the kidnappers had initially demanded US$5 million.14 The kidnappers dropped their demands to US$2.8 million the following week after formal police investigations had begun, then lowered the ransom again to US$1 million when they realized that the authorities were close to tracking them down. They then lowered it again to US$300 000 the day before Adatia’s rescue. Three kidnappers were arrested during the operation.15

Figure 5 Year-on-year in kidnappings in Mozambique (April to April, with the exception of 2020).

Source: Annual reports from the Procuradoria-Geral da República de Moçambique to parliament (2014–2019); media reports.

However, such detail about a kidnapping is rare. While at least five of the eight individuals kidnapped in Mozambique in 2020 have been subsequently released or rescued, the fate of the detainees is not always publicly known. In addition, police and victims alike are often unwilling to publicly discuss ransom payments, and the authorities do not release much information regarding the arrests and prosecutions of kidnappers.

However, recent kidnappings suggest that similar groups of actors may be involved in multiple operations. Information obtained by police following the arrest of Adatia’s kidnappers led to the rescue of Manish Cantilal later the same day, indicating possible operational linkages between the two gangs. Furthermore, the group behind the November 2019 abduction of Shelton Lalgy (nephew of the owner of the Lalgy logistics company) is also reported to have kidnapped an Asian citizen named Balesh Moulal – a trader based in the city of Maxixe, in late 2019. One of the members of the group was arrested in Beira City while in the process of orchestrating another kidnapping.16

Signs of state and security involvement

There is evidence to suggest that state officials – including police and military officers – may be implicated in some kidnappings. According to Chaves, a senior official of the Municipal Council of Maputo City was implicated in the kidnapping of Adatia,17 while SERNIC stated that a member of the Mozambique Armed Defence Forces was one of three people arrested on suspicion of having kidnapped Shelton Lalgy in the city of Matola.18 (Lalgy was released in February after a ransom was paid.) SERNIC named the officer as the main suspect in the supply of arms and ammunition used by the group in its raids.

But according to Antonio Frangoulis, the lawyer and former director of the police-investigations branch which preceded SERNIC, those arrested by police are usually just ‘small fish,’ such as guards or domestic workers. ‘The real planners and principals of these crimes are in the offices commanding the actions and are untouchable,’ he said.

There are clear signs – such as repeated failures to investigate kidnappings and prosecute the perpetrators – that the Mozambican police and associated institutions are influenced by criminal networks, including groups that carry out kidnappings. ‘What we see is the criminalization of the state in which groups of bandits have the ability to manage decisions that should be taken against them, which is why you see this passivity and impunity towards them and their actions,’ Nuvunga said.19

This pattern of impunity was broken in the case of Rizwan Adatia. In the view of a Maputo-based businessman interviewed for the Risk Bulletin, intense pressure from the Indian government on the Mozambican authorities to find and release Adatia (an Indian citizen) brought about the rescue. ‘This time they had kidnapped the wrong person,’ he said.20

The same climate of impunity also surrounds other crimes in Mozambique, such as assassination. Mozambican police officers have reportedly formed so-called ‘death squads’ to carry out state-sponsored assassinations. As reported in a previous Risk Bulletin issue, the assassination of election observer Anastácio Matavel in October 2019 was carried out by agents of the Rapid Intervention Unit, which is linked to the Mozambican police.21 The weapons used in the crime had been sourced from state warehouses.22

While the trial of Matavel’s killers was a significant step in revealing the existence of the police death squads – six officers were sentenced to between three and 24 years in prison – the masterminds of the crime were not identified. The legal counsel for the general command of the Mozambican police argued that the officers had acted in their individual capacities, and not on behalf of the state.23

The July 2020 shooting of Vuma, the business leader, was also reportedly linked to the police. A security guard who witnessed the attack told the press that Vuma had identified the shooter as ‘Salimo’. Ongoing press investigations have identified ‘Salimo’ as a police officer who has been hired as a hitman by wealthy individuals.24

It remains unknown whether other groups could be involved in the kidnapping in Mozambique, such as other organized-crime groups or business rivals contracting kidnappings to be carried out on their competitors. Manish Cantilal, one of the kidnapping victims in 2020, had previously been arrested in 2014 on suspicion of involvement in several kidnappings, but was later cleared.25 This came after a judge, Dinis Silica, was gunned down the day he was due to make a ruling on Cantilal’s case.26 Investigations of comparable kidnappings of businessmen in the Pakistani and Indian communities in South Africa have raised suspicions of the involvement of Pakistan-linked mafia groups.27

State action and inaction

At the end of 2015 – President Filipe Nyusi’s first year in office and a year in which 19 people were kidnapped – the then-interior minister Jaime Basilio Monteiro assured the public that the police would get the situation under control.28 Since then, the authorities have attempted to encourage information-sharing to help trace the movements of kidnappers. Since the locations used by the kidnappers are generally rented houses, the Mozambican police and local authorities have called on the owners of short-term rented properties to register them with licensed real-estate agents. Landlords must also inform the local authorities of the identities of new tenants.

In addition, the Interior Minister Amade Miquidade told parliament in May that the financial sector should play more of a role in helping identify kidnappers, as the transfer of large sums of money to pay ransoms could be used to trace criminals.29 Banks do not currently have any specific measures in place to deal with this type of crime, according to the Mozambique Financial Information Office, a government financial watchdog.

But cooperation with private partners is likely to yield scant results if the state itself does not act. Sources have told the GI-TOC that, despite repeated pledges, the Mozambican authorities have not passed any reforms or visible measures to prevent kidnappings.30 This situation, combined with an apparent lack of will to investigate and prosecute kidnappers, may further empower the kidnappers to expand their operations. In the words of Alberto Ferreira, an academic and opposition parliamentarian: ‘as in southern Italy where the mafiosi control political power, here too the kidnappers are in control’. Looking to the future, Ferreira warns that impunity for kidnapping groups may invite other criminal groups to move into this business.

Notes

-

Luis Nhachote, Caso VUMA: “Reiteramos o nosso repúdio pessoal e colectivo deste crime bárbaro” - Álvaro Massinga, Moz24Horas, 15 July 2020, https://www.moz24h.co.mz/post/caso-vuma-reiteramos-o-nosso-rep%C3%BAdio-pessoal-e-colectivo-deste-crime-b%C3%A1rbaro-%C3%A1lvaro-massinga. ↩

-

Mozambique: CTA chairman Agostinho Vuma shot and hospitalised, Club of Mozambique, 12 July 2020, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/mozambique-cta-chairman-agostinho-vuma-shot-and-hospitalised-165415/. ↩

-

Tomás Queface, Maputo continua a ser a capital da impunidade…, Twitter post, 5.57 p.m., 11 July 2020, https://twitter.com/tomqueface/status/1281965762975019008. ↩

-

Luis Nhachote, Caso VUMA: “Reiteramos o nosso repúdio pessoal e colectivo deste crime bárbaro” - Álvaro Massinga, Moz24Horas, 15 July 2020, https://www.moz24h.co.mz/post/caso-vuma-reiteramos-o-nosso-rep%C3%BAdio-pessoal-e-colectivo-deste-crime-b%C3%A1rbaro-%C3%A1lvaro-massinga. ↩

-

Informação Anual do PGR à Assembleia da República, 2014-2019, http://www.pgr.gov.mz/por/Documentacao/Informacao-Anual-do-PGR-a-Assembleia-da-Republica. ↩

-

Informação Anual do PGR à Assembleia da República, 2014-2019, http://www.pgr.gov.mz/por/Documentacao/Informacao-Anual-do-PGR-a-Assembleia-da-Republica. ↩

-

Bebito Manuel Alberto, Entre O Silêncio E O “Lucro”: Um Estudo Sobre A Onda De Sequestros Nas Cidades De Maputo e Matola, em Moçambique, Período De 2011–2013, Masters dissertation, Universidade Federal Da Bahia Faculdade De Filosofia E Ciências Humanas, 2015, https://repositorio.ufba.br/ri/bitstream/ri/19017/1/DISSERTAÇÃO%20BEBITO%20MANUEL%20ALBERTO.pdf. ↩

-

Informação Anual do PGR à Assembleia da República, 2014-2019, available at, http://www.pgr.gov.mz/por/Documentacao/Informacao-Anual-do-PGR-a-Assembleia-da-Republica. ↩

-

Depois de Rizwan Adatia: Resgatado empresário Manish Cantilal, Notícias, 20 May 2020, https://www.jornalnoticias.co.mz/index.php/capital/maputo/97157-depois-de-rizwan-adatia-resgatado-empresario-manish-cantilal. ↩

-

Government of Mozambique, Informação Anual de 2017 do Procurador-Geral à Assembleia da República, March 2017, https://www.pgr.gov.mz/por/Documentacao/Informacao-Anual-do-PGR-a-Assembleia-da-Republica. ↩

-

Interview with Rodrigo Rocha, 8 June 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Interview with a Maputo-based businessman, Maputo, 4 June 2020. ↩

-

Interview with Adriano Nuvunga, 8 June 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Mozambique: Second kidnapped businessman rescued, Agência de Informação de Moçambique, via AllAfrica, 21 May 2020, https://allafrica.com/stories/202005210546.html. ↩

-

Depois de Rizwan Adatia: Resgatado empresário Manish Cantilal, Notícias, 20 May 2020, https://www.jornalnoticias.co.mz/index.php/capital/maputo/97157-depois-de-rizwan-adatia-resgatado-empresario-manish-cantilal. ↩

-

Mozambique: Police Arrest Alleged Kidnappers, Agência de Informação de Moçambique, via AllAfrica, 9 April 2020, https://allafrica.com/stories/202004090998.html. ↩

-

Raptos Em Maputo, Miramar, 22 May 2020, http://miramar.co.mz/noticias/raptos-em-maputo/. ↩

-

Última Hora: Raptado sobrinho do empresário Lalgy, O País, 28 November 2019, http://opais.sapo.mz/ultima-hora-raptado-sobrinho-do-empresario-lalgy; Curandeiro e militar no rapto do filho de Lalgy, Noticias, 8 April 2020, https://www.jornalnoticias.co.mz/index.php/sociedade/96597-curandeiro-e-militar-no-rapto-do-filho-de-lalgy. ↩

-

Interview with Adriano Nuvunga, by phone, 8 June 2020. ↩

-

Interview with a Maputo-based businessman, Maputo, 4 June 2020. ↩

-

Risk Bulletin of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa, 2, November 2019, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/GI-Risk-Bulletin-02-29Nov.v2.Web_.pdf. ↩

-

Boletim Sobre Direitos Humanos, The role of the Judicial Court of the Province of Gaza and of the Public Prosecutor in the pursuit of the public interest and the achievement of justice in the case of Anastácio Matavele, CDD Mozambique, 12 July 2020, https://cddmoz.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/The-role-of-the-Judicial-Court-of-the-Province-of-Gaza-and-of-the-Public-Prosecutor-in-the-pursuit-of-the-public-interest-and-the-achievement-of-justice-in-the-case-of-Anast%C3%A1cio-Matavele.pdf. ↩

-

Boletim Sobre Direitos Humanos, “Esquadrão de morte” condenado, mas Julgamento não esclarece o Crime!, CDD Mozambique, 19 June 2020, https://cddmoz.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/SENTEN%C3%87A-DO-%E2%80%9CCASO-MATAVELE%E2%80%9D_-%E2%80%9CEsquadr%C3%A3o-de-morte%E2%80%9D-condenado-mas-Julgamento-n%C3%A3o-esclarece-o-Crime.pdf. ↩

-

Raul Senda, Crime organizado instala terror, Savana, 17 July 2020, https://macua.blogs.com/files/savana1384-17.07.2020.pdf. ↩

-

Joseph Hanlon, Mozambique News Reports and Clippings, Open University, 17 March 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/held-to-ransom-an-overview-of-mozambiques-kidnapping-crisis/. ↩

-

Julian Rademeyer, Held to Ransom: An overview of Mozambique’s kidnapping crisis, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 20 December 2015, https://globalinitiative.net/held-to-ransom-an-overview-of-mozambiques-kidnapping-crisis/. ↩

-

Vincent Cruywagen, Abductors scrutinise businessmen’s financials before kidnapping them, IOL, 25 September 2019, https://www.iol.co.za/capeargus/news/abductors-scrutinise-businessmens-financials-before-kidnapping-them-33525739; and Graeme Hosken, Polish businesswoman kidnapped outside Sandton hotel, 17 April 2018, https://t.co/Y0wswVaRjE?amp=1. ↩

-

Lionel Matias, Cerco aos mandantes dos raptos em Moçambique, Deutsche Welle, 9 December 2015, https://www.dw.com/pt-002/cerco-aos-mandantes-dos-raptos-em-mo%C3%A7ambique/a-18908364. ↩

-

Ministro do Interior diz que setor financeiro é importante no combate aos raptos, Notícias, 27 May 2020, https://noticias.sapo.mz/actualidade/artigos/ministro-do-interior-diz-que-setor-financeiro-e-importante-no-combate-aos-raptos. ↩

-

Interviews with members of civil society based in Maputo, 8 June 2020, by phone. ↩