Stricter measures targeting remittance companies risk driving financial flows to Somalia underground.

Remittance companies provide a critically important mechanism for transferring cash to Somalia, where the fledgling formal financial sector remains largely isolated. Despite improvements, Somalia still struggles with weak financial management, a climate of impunity regarding government corruption and the destabilizing threat posed by the homegrown Islamist militant group, Al- Shabaab. As a result, commercial banks in Somalia remain largely cut off from global financial flows and are unable to accept or initiate international transfers.

For the vast majority of individuals and entities living or operating in Somalia, international financial transactions require the use of remittance providers, often, and increasingly misleadingly, referred to as hawalas.1 While traditional hawala operations in the UK still exist, major remittance providers serving Somalia are now closely affiliated or have partnered with the recently established Somali domestic banks. As such, the major remittance providers in the UK are increasingly attempting to implement anti-money laundering and counter-terror financing (AML/CTF) protocols and know-your-customer (KYC) measures to meet basic international regulatory requirements and integrate their services into the regional and global economy. However, major challenges remain.

UK regulators crack down on payment service providers (PSPS)

The majority of remittances received in Somalia are sent from countries with significant Somali diaspora communities. In the UK – which hosts by far the largest Somali diaspora community in Europe – there remain concerns regarding the strength of AML/CTF and KYC systems in place for many authorized Payment Service Providers (PSPs), including all remittance providers. On 9 July 2020, the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) published a ‘Dear CEO’ letter addressed to all PSPs that outlined a plethora of weaknesses in the industry and concluded with the stark warning that it would ‘act swiftly and decisively’ if the companies failed to meet their expectations.2 These weaknesses ranged from a failure to establish sufficient safeguarding measures and implement effective AML procedures to simple record- management and reporting deficiencies.

At the heart of these weaknesses lie the issues of cash, identity and agent integrity. The traditional remittance model depends on a network of multiple agents who are located throughout the UK and deal exclusively in cash, which is collected from customers for processing and onward transfer. The use of cash means that financial flows are difficult to trace, leaving the system open to abuse from those engaging in money laundering or terrorism financing. While senders of remittances are required to provide identity documents, which are then stored in the providers’ transfer systems, the process still ultimately depends on the integrity of the agents involved. A 2019 investigation by the Norwegian Financial Supervisory Authority into an Oslo-based agent of a major Somali remittance provider, Taaj, found several customers had had their identity documentation misused to transfer funds on behalf of other customers seemingly keen to conceal their identities.3

‘Lack of risk appetite’ among UK banks

According to UK FCA regulations, PSPs (including hawala remittance providers) which process more than €3 million (US$3.5 million) a month are required to safeguard client funds. This first involves segregating the funds provided by clients for transfer from any associated fees and then securing them, either in a dedicated bank account and/or through insurance. Remittance providers serving Somalia, however, are struggling to achieve either.

Since the early 2010s, starting with the high-street brands and gradually extending to smaller private and specialist institutions, UK banks have withdrawn the provision of many remittance providers’ standard business banking facilities and refused to open new accounts, with banks almost always citing ‘a lack of risk appetite’. As the time of writing, only one UK-based insurance broker openly offers safeguarding insurance, but they too have reportedly demonstrated a reluctance to work with remittance providers serving Somalia.

Customers wait to collect money at a branch of the Juba Express money transfer company in Mogadishu, Somalia.

© Mohamed Abdiwahab/AFP via Getty Images

This situation initially prompted the growth of a new industry of consultants and consulting firms offering to leverage their established networks of friendly banks to establish the necessary account facilities. However, according to the manager of one such entity, their options are now also drying up, particularly following the July letter sent by the FCA, which prompted a rapid acceleration of account closures among the last few formal banking institutions willing to serve remittance companies.4 Banks increasingly present remittance providers with convoluted application processes, which for certain African states ultimately amount to a denial of services.5

There have been two major consequences of banks’ disengagement from the remittance sector. The first is the inability for many operators to meet FCA requirements of segregating and securing client funds. This inability is ultimately forcing institutions either to cease operations or to spread their operations among a network of Small Payment Institutions (SPIs), which maintain turnovers below the threshold of larger companies. These SPIs each use the original institution’s transfer system but are held to lower regulatory and accountability standards.

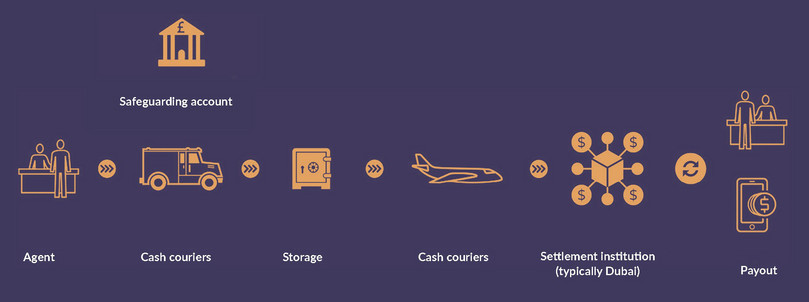

The second consequence of banks’ de-risking is the entrenchment of the cash model. As a result, cash has to be physically transported from agent to courier and onwards to overseas settlement institutions, often based in the Gulf.6 During the coronavirus pandemic, the suspension of flights by cash couriers to Gulf countries has put particular strain on the ability of remittance companies to maintain financial flows.

The receiving end of remittances

Unsurprisingly, the receiving end of remittances represents the most challenging environment for regulation and the monitoring of effective AML/CTF measures. In theory, the growing prevalence in Somalia of mobile-money platforms – where a mobile phone and associated electronic account is used to transfer funds and make payments – should make it easier to trace the digital path from sender to recipient compared to other cash-dependent economies.

Officially, measures are already in place to register users of mobile-money platforms, but such measures are often ineffective. UN monitors investigating mobile money in 2016 found that accounts with EVC+ (most likely to be the largest mobile-money platform in Somalia, and closely associated with the Taaj remittance platform) could be opened remotely, ‘with no physical presence of the user required, nor photo ID’.7 More recent reporting by the monitors in 2018 demonstrated the extent to which Al-Shabaab relies on the EVC+ platform for its own domestic financial transfers, highlighting the vulnerability of mobile-phone platforms to terrorism financing.8

Figure 3 The mechanics of typical remittance transfers from Europe to Somalia.

Source: GI-TOC

There are legitimate grounds for maintaining a flexible approach to KYC policies and engagement and cooperation with domestic regulatory bodies in Somalia, where there is a humanitarian imperative to maintain the flow of remittances. Remittance-service providers operating throughout rural parts of southern and central Somalia cite the safety of their staff from Al-Shabaab militants – who do not wish to leave a financial footprint – as their rationale for limited compliance and cooperation with domestic regulatory bodies.

KYC procedures in Somalia are also dependent on customers both possessing identity documents and being willing to present them, as well as the willingness and ability of financial agents to verify such documentation. This remains some way off in Somalia, not least because of the scarcity of identity documents among the population and the widespread availability of falsified documents (including passports).

But despite the imperative to keep the remittances flowing, it is inarguable that the lack of a functioning financial-regulatory and national-identification system in Somalia has long made the system vulnerable to abuse by organized-crime groups. A forthcoming study by the GI-TOC will detail how the remittance system underpins the Yemen–Somalia arms trade.

Implications of restrictions on remittance providers

The increasingly restrictive environment for remittance providers serving the Somali community comes at a time when many are already facing challenges, with a recent fall in business prompted in large part by the coronavirus pandemic. Lockdown measures in the UK led to the temporary closure of many agents’ premises and made customers reluctant to venture out, withdraw cash and physically carry it to the nearest agent.

The permanent closure of remittance providers serving Somalia would have a significant and immediate humanitarian impact.9 Somalia is facing its own coronavirus crisis, with among the world’s least-prepared health sectors.10 Somalia has also experienced severe flooding along river basins and an invasion of desert locusts, raising the prospect of food insecurity and famine conditions which could ultimately claim many more lives than COVID-19.

The economic impact of the restrictions may also have longer-term repercussions. The formal financial sector remains in the early stages of revival in Somalia and trust in it remains limited among the general population. Given the interconnectedness of banks, mobile-money platforms and remittance providers, the collapse of one component is likely to dent faith in the others, and could ultimately result in a cash run on financial institutions.

In the UK, the closure of remittance providers is likely to undermine the broader aims of financial regulation. One foreseeable outcome is that financial flows from the UK to Somalia will be driven futher underground, and that in the absence of affordable formal and regulated remittance services, an informal market for the physical transportation of cash across borders will flourish.

For different reasons – to do with over-regulation at the receiving end – this is already largely the case for remittances sent globally to Eritrea. According to some estimates, at least two-thirds of remittances sent to Eritrea are now made informally. Individuals face severe risks when importing cash for family and friends in suitcases through Asmara International Airport. Yet they are willing to do so to avoid being forced to accept government fees and the official exchange rate, which almost halves the money’s purchasing power once converted into local currency.11

A way forward?

UK-based remittance providers serving Somalia are dangerously close to being permanently shut down, which would leave a vacuum for informal actors to fill. Creative solutions need to be found to protect remittance providers while also strengthening the accountability of transactions.

A shift away from cash to digital transactions – requiring debit/credit card transactions or bank transfers to send remittances – would reduce opportunities to exploit existing weak systems and the loopholes among agents in the UK to send funds anonymously, while strengthening traceability of cross-border financial flows. This would require the re-structuring and modernization of the Somali remittance business model. But it would also require facilitation by UK banking institutions which currently have little, if any, incentive to risk engaging with remittance providers serving Somalia.

Notes

-

Over the past decade or so, the larger Somali remittance providers have been keen to disassociate themselves from the term hawala, which is often considered to imply an informal transaction process based on trust between the sending and receiving agents. ↩

-

UK Financial Conduct Authority, Portfolio strategy letter for payment services firms and e-money issuers, 9 July 2020, https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/correspondence/payment-services-firms-e-money-issuers-portfolio-letter.pdf. ↩

-

Finanstilsynet, Tilsynsrapport og tilbakekall av konsesjon, 6 February 2020, https://www.finanstilsynet.no/contentassets/f9ac0d2c986b4fdaada2270b36932ea5/tilsynsrapport-og-tilbakekall-av-konsesjon-ttc-finans-as.pdf. ↩

-

Author interview, July 2020. ↩

-

In some instances, remittance firms have found creative solutions to adhering to safeguarding regulations, using layers of affiliated institutions with varying levels of FCA authorization to eventually establish the requisite account in their name with a bank that is then ostensibly several steps removed. While currently considered legitimate, this method is vulnerable to changing FCA regulations and/or bank policies, and may well prove unsustainable in the long term. ↩

-

Done properly, the practice remains entirely legitimate and several internationally recognized security firms provide fully insured international cash couriering services. ↩

-

United Nations Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea, Somalia report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea submitted in accordance with resolution 2244 (2015), 31 October 2016, https://www.undocs.org/S/2016/919. The report cites interviews with detained members of Al-Shabaab in Mogadishu in 2016. ↩

-

United Nations Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea, Somalia report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea submitted in accordance with resolution 2385 (2017), 9 November 2018, https://undocs.org/S/2018/1002. ↩

-

Sherine El Taraboulsi-McCarthy, The challenge of informality: Counter-terrorism, bank de-risking and financial access for humanitarian organisations in Somalia, Overseas Development Institute, June 2018, https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12258.pdf. ↩

-

The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, Civil Society Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin, Issue 9, June–July 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Civil-Society-Observatory-of-Illicit-Economies-in-Eastern-and-Southern-Africa-Risk-Bulletin-9.pdf. ↩

-

Berhane Tewolde, Remittances as a tool for development and reconstruction in Eritrea: An economic analysis, Journal of Middle Eastern Geopolitics, 1, 2. ↩