Iranian weapons supplied to the Houthis may end up in Somalia.

On 24 June 2020, Saudi-led coalition forces seized a dhow carrying Iranian weapons to Houthi insurgents in Yemen. The seized consignment included nearly 1 300 assault rifles, as well as sniper rifles, rocket-propelled grenade launchers, and anti-tank guided missiles.1 The June seizure was the latest in a number of similar naval interdictions dating back to late 2015.2 With the UN Security Council arms embargo on Iran scheduled to expire in mid-October, US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, used the June interdiction to urge the council to extend the measures.3

Such seizures provide compelling evidence for the established illicit movement of weapons from Iran to Yemen. However, evidence has emerged to suggest that some of these Iranian weapons may subsequently be trafficked by criminal networks into the Horn of Africa from Yemen (or even be diverted while en route to Yemen). GI-TOC research has indicated that there may be a plausible link between Iranian arms supplies to the Houthis and weapons smuggled into Somalia. In late June 2020, the GI-TOC contacted Jabir Al-Haadi, an arms dealer based in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. His name has been changed here. In approaching Al-Haadi, the GI- TOC assumed the persona of an Arabic-speaking Somali national who lived in Nairobi and went by the alias ‘Jama’.4 Jama told Al-Haadi that he was attempting to broker an arms deal on behalf of a (fictitious) South Sudanese client.

Between 27 June and 5 July, Al-Haadi and Jama exchanged dozens of recorded voice messages on the WhatsApp platform. Over the course of these exchanges, Al-Haadi shared detailed information about his operation, including his current weapons stocks, his associates and preferred means of receiving financial transfers. He also provided several photographs of weapons held at his storehouse in Sana’a, including one showing the serial number and related markings of a recently manufactured Chinese Type 56-1 rifle.

Based on this serial number, the GI-TOC subsequently determined that the rifle shared characteristics with weapons reportedly provided by Iran to the Houthi movement. Moreover, a Type 56-1 rifle with a highly similar serial number sequence had been documented in central Somalia in April 2019. The GI-TOC’s research tentatively indicates the existence of illicit-arms smuggling networks that see Iranian arms intended for Yemen end up in Somalia, and potentially beyond.

The history of the Yemen-Somalia arms trade

Somalia has been under a UN arms embargo since 1992, making all imports of military equipment into the country (outside of specified Security Council exemptions) violations of international law. Since that time, Somali arms importers have looked to Yemen as their primary source for illicit arms, drawing on the centuries-old cultural and commercial ties between the two countries as well as the widespread availability of small arms and ammunition in Yemen. (Even before the outbreak of the current civil war in 2015, Yemen had the second-greatest per capita ownership of weapons, after the US.)5

Puntland, a semi-autonomous region comprising most of the north-eastern corner of Somalia, is the primary point of entry for illicit arms into the country. Illicit-arms imports into Puntland typically consist of light weapons such as pistols, AK-pattern rifles, rocket-propelled- grenade launchers and Soviet-pattern machine guns, together with their respective ammunition.

Arms smuggling into Puntland typically takes one of two forms. The first and more common method involves small-scale shipments being brought by speedboat across the Gulf of Aden from the Yemeni coast, most often from the vicinity of the littoral towns of Mukalla, B’ir Ali, Balhaf and Ash Shihr. The second method is more convoluted and piggybacks off the Iran–Yemen arms connection, in which ocean-faring dhows transport larger weapons shipments – often including surface-to-air missiles and other sophisticated weaponry – from Iran’s Makran coast. Seizures of several Iranian dhows by international naval forces since late 2015 have yielded evidence that suggests it may be common practice for light weapons and ammunition to be transhipped to Somalia by criminal networks using smaller vessels before the dhows’ arrivals in Yemen.6

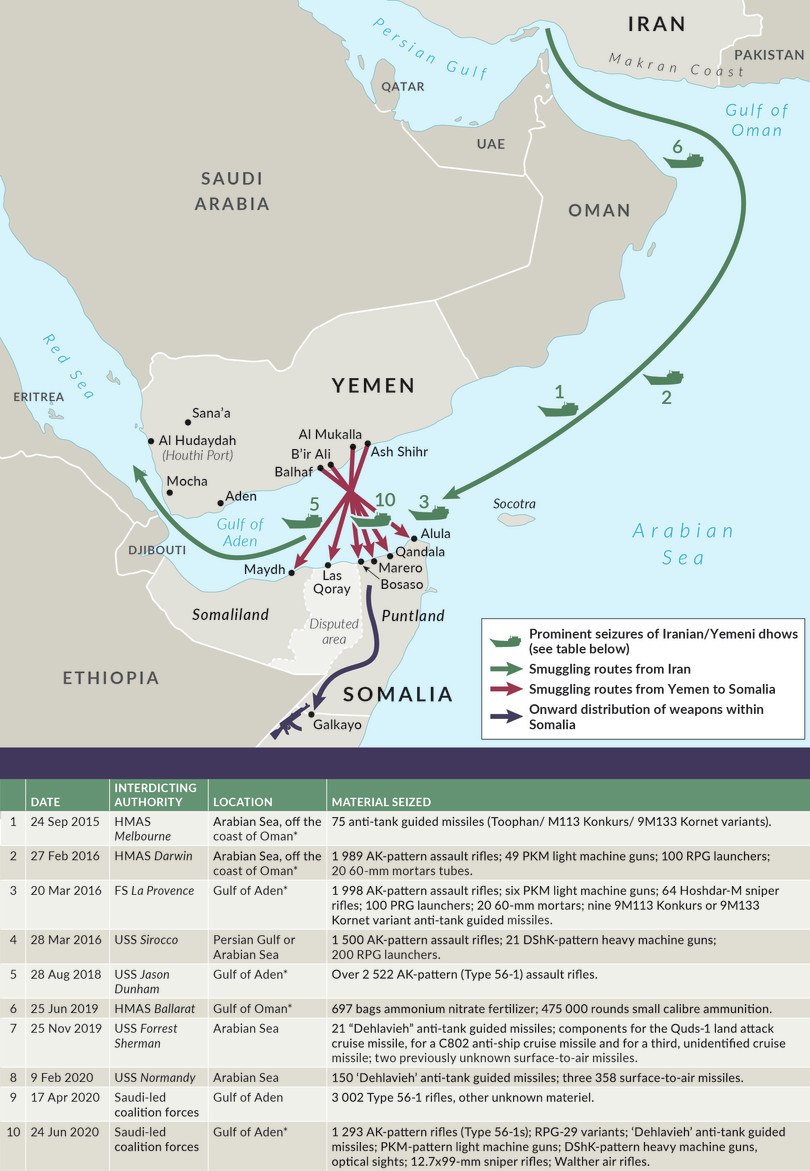

Figure 1 Arms smuggling routes to Somalia from Yemen and Iran, and approximate locations of prominent dhow seizures.

NOTE: * Indicates seizures shown on the accompanying map.

SOURCE: Reports of the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen, US Central Command, Australian Navy, the GI-TOC.

The anatomy of an (abortive) arms deal

Over the course of conducting research for a forthcoming study on the Yemen–Somalia arms trade, the GI-TOC found contact information for Jabir Al-Haadi, an arms dealer based in Sana’a. Using the fictitious identity ‘Jama’, in late June the GI-TOC contacted Al-Haadi with the aim of better understanding the modalities of the Yemen– Somalia arms trade. Following brief introductions, Al- Haadi proceeded straight to business. He began to inform Jama of the types of weapons in his possession and requested that Jama provide details on the requirements of Jama’s (fictitious) South Sudanese client.

In response, Jama sent Al-Haadi a list of small arms and ammunition supposedly requested by his South Sudanese client. The requested consignment – worth upwards of US$5 million – was calibrated to test whether a Yemeni arms dealer would be capable of scaling up his operation to meet higher-than-typical demand. Within two days, Al-Haadi replied with a list of prices for various assault rifles, light machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades and light ammunition. The GI-TOC’s research indicates that the figures he quoted were higher than typical wholesale prices in Yemen, though Al-Haadi insisted that he was willing to negotiate.

Hi Sheikh Jama, Italian or Israeli type [weapons], I have all that… Since you communicated with me, then it means you can trust me. We trust in God and we work together. Write for me what is required, the types and quantities in a list and I’ll bring you the prices in two days’ time. So if you trust me as a person and deal with me, just tell me the various types you want.

| Abir Al-Haadi’s price list | |

|---|---|

| Type 56-1 (AK-pattern) assault rifle. | US$1 900/unit AR-M9F assault |

| AR-M9F assault rifle | US$2 400/unit |

| PK-pattern light machine gun | US$6 000/unit |

| Type 69 rocket-propelled-grenade rounds | US$90/round |

| 7.62×39mm (AK-pattern rifle) ammunition | US$0.70/round |

| 7.62×54mm (PKM) ammunition | US$1.50/round |

| 12.7×108mm (DShk heavy machine gun) ammunition | US$2.30/round |

A network of small-scale suppliers

Al-Haadi told Jama that he did not personally have the capacity to fill the order and would have to source the materiel from various arms dealers located throughout Yemen:

Look, the quantities of the equipment are not available, but we can gather them. So, if you’re serious, and now that you have the prices, prepare yourself, and send me a deposit tomorrow afternoon… I’ll send you the name of the receiver and I’ll tell you the hawala [money broker] you’ll use to send, so that we can start going to the provinces and regions and gather from the traders, giving each of them some deposit, until we get all the quantities. You contact me and I’ll tell you where to transfer the money to…

Al-Haadi also told Jama that arms and ammunition were in such demand in Yemen itself that if he hesitated to finalize the order, it would no longer be possible to source the desired quantities. ‘Yemen needs weapons more than any other country in the world,’ he told Jama. ‘These weapons and ammunition are our breakfast, lunch and dinner. We consume them more than food.’

While this assertion may have been a negotiating tactic on the part of Al-Haadi, it is also possible that the ongoing civil war has reduced the excess supply of weapons in Yemen. If so, Al-Haadi’s assertion may belie the argument made in some quarters that the conflict has led to a glut of arms available for export.7

Type 56-1 rifles: a tentative link to Iran

Al-Haadi also provided Jama with several photographs of his available stock, including images from his storehouse of several AK-pattern rifles with characteristics consistent with Chinese-manufactured Type 56-1s.

Type 56-1 rifles photographed in Muriidi Ahmed’s Sana’a storehouse, July 2020.

© GI-TOC

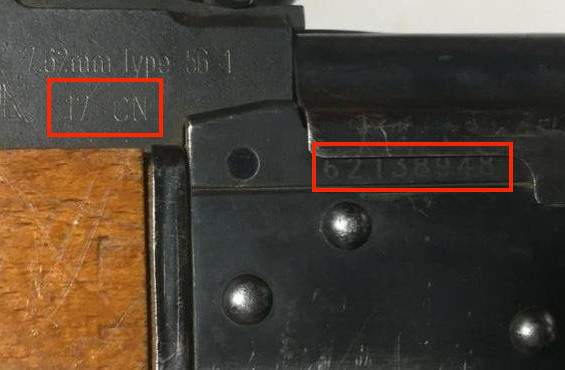

Detailed markings of one Type 56-1 rifle, including ‘17 CN’ (indicating a 2017 date of manufacture), and serial number 62138948.

© GI-TOC

The serial number on one of Al-Haadi’s rifles – 62138948 – allowed the GI-TOC to uncover a telling connection between Yemen and Somalia. In April 2019, a Type 56-1 rifle with a serial number also beginning with the sequence ‘621’ was documented in the possession of an arms dealer in the central Somali city of Galkayo.8 The identical three digits of the serial numbers strongly suggest that the two rifles had belonged to the same illicit consignment originating in Yemen.

A small seizure of smuggled weapons in the port city of Bosaso by the Puntland authorities, also in April 2019, provided another clue as to the provenance of the rifles. A photograph of the seizure, seen by the GI-TOC, shows a collection of 19 rifles that included weapons which appeared to be Type 56-1s. It is therefore plausible to speculate that that a certain quantity of Type 56-1 rifles that reached Somalia from Yemen in April 2019 may have may have entered the country at Bosaso before being traded onwards, reaching at least as far as an arms dealer in Galkayo.

Type 56-1 rifle seized from a dhow interdicted by the USS Jason Dunham in August 2018.

© UN Panel of Experts on Yemen

Markings of a Type 56-1 rifle seized by the USS Jason Dunham. The rifle bears an identical ‘17 CN’ marking, and a similar serial number, to the Type 56-1 photographed in Muriidi Ahmed’s storehouse, above.

© UN Panel of Experts on Yemen

How these rifles reached Yemen in the first place is also open to speculation, but there are strong indications that they may have been part of arms deliveries from Iran intended for Houthi insurgents. Type 56-1 rifles bearing the markings CN-17 and CN-18 – such as the one in the photograph provided by Al-Haadi – are frequently documented in Yemen and are believed to originate in Iran.9 Indeed, the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen, a Security Council body tasked with monitoring the arms embargo on the country, documented that similar Type 56-1 rifles had been seized from a dhow interdicted by the USS Jason Dunham in August 2018.10 Type 56-1 rifles with serial numbers beginning with the sequence ‘621’ were also seized aboard a Yemen-bound dhow interdicted by Saudi-led coalition forces in the Gulf of Aden on 17 April 2020.11

The Type 56-1 rifle in Al-Haadi’s storehouse in Sana’a provides compelling – albeit very preliminary – evidence of the diversion of Iranian arms supplies intended for Yemen to at least as far as central Somalia. Moreover, many arms smuggled from Yemen are also reported to be sold on by middlemen to countries such as Kenya, Mozambique, Tanzania, South Sudan and Central African Republic.12 It is therefore possible that spillover from the Yemen conflict may have wider security implications for the East Africa region.

The ‘arms deal’ falls through

Al-Haadi requested that Jama facilitate a transfer of US$100 000 from his fictitious South Sudanese client as a down payment for the order. He subsequently transmitted the name of an individual who would collect the funds at a hawala money-transfer bureau in Sana’a on his behalf. Over the course of their communications, Al-Haadi became increasingly frustrated that Jama had failed to transfer the down payment. ‘Jama… Frankly, we have worked and we got tired,’ he said. ‘We did our part. Now, the deadline for [the South Sudanese client] is 12 p.m. … if they don’t respond, tell them we will cancel and there will be no need to disturb us anymore.’

Ultimately, on 5 July 2020 Al-Haadi informed Jama that he was unable to supply the requested quantities and ceased his communications:

Assalamu aleikum Sheikh Jama. I tried to get the quantities. It was very difficult to get such large quantities. Very difficult to get these quantities in Yemen… So it’s impossible to provide your order. Moreover, I was very enthusiastic to work with you, but your people have some kind of fear or something like that and to add to that the quantities are not available. So frankly, we cancel this, the quantity is not available. I would have liked that we work together but I can’t. My greetings and may God be with you.

Al-Haadi’s willingness to communicate openly over a messenger application and furnish detailed information about the nature of his arms business to a new acquaintance was indicative of the environment of impunity in which he operates. From the GI-TOC’s exchanges with Al-Haadi, he appeared to be a small-scale supplier who primarily services domestic requirements in Yemen. However, his possession of assault rifles similar to those documented in Somalia provides an interesting window into the possibility of a common origin in Iran. While far more data is required before any definitive conclusions can be drawn, the Al-Haadi case study suggests interesting avenues for future research.

Notes

-

Confidential report seen by the GI-TOC, July 2020. ↩

-

On 9 February 2020, the USS Normandy interdicted a weapons-laden dhow in the Arabian Sea. The seized arms included Iranian-manufactured Dhelavieh anti-tank guided missiles, the 351 land-attack cruise missile, and the C802 anti-ship cruise missile. U.S. Central Command, U.S. Dhow Interdictions, 19 February 2020, https://www.centcom.mil/MEDIA/NEWS-ARTICLES/News-Article-View/Article/2087998/us-dhow-interdictions/. ↩

-

Jonathan Landay and Humeyra Pamuk, Pompeo says U.S. seized Iranian weapons on way to Houthi rebels in Yemen, Reuters, 8 July 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-iran-pompeo/pompeo-says-u-s-seized-iranian-weapons-on-way-to-houthi-rebels-in-yemen-idUSKBN2492AV. ↩

-

Alias has been changed. ↩

-

Michael Horton, Yemen: A dangerous regional arms bazaar, Terrorism Monitor, 17 June 2017, https://jamestown.org/program/yemen-dangerous-regional-arms-bazaar/. ↩

-

UN Panel of Experts on Yemen, Final report of the Panel of Experts in accordance with paragraph 6 of resolution 2266 (2016), 27 January 2017, https://www.undocs.org/S/2018/193; and United Nations Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea, Somalia report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea submitted in accordance with resolution 2317 (2016), 8 November 2017, https://www.undocs.org/S/2017/924. ↩

-

See, for instance, Michael Horton, Arms from Yemen will fuel conflict in the Horn of Africa, Terrorism Monitor, 17 April 2020, https://jamestown.org/program/arms-from-yemen-will-fuel-conflict-in-the-horn-of-africa/. ↩

-

Information provided to the GI-TOC by a confidential source, 14 July 2020. ↩

-

Interviews with two international arms experts, by text message, 14 July 2020. ↩

-

UN Panel of Experts on Yemen, Final report of the Panel of Experts in accordance with paragraph 6 of resolution 2402 (2018), 25 January 2019, https://undocs.org/en/S/2019/83. ↩

-

Interview with a confidential source by text message, 14 July 2020. ↩

-

Michael Horton, Arms from Yemen will fuel conflict in the Horn of Africa, Terrorism Monitor, 17 April 2020, https://jamestown.org/program/arms-from-yemen-will-fuel-conflict-in-the-horn-of-africa/. ↩