The pandemic has driven unprecedented shifts in human-smuggling patterns to Mayotte.

The measures taken by states to slow the spread of the coronavirus pandemic have disrupted human-smuggling dynamics across the globe, including the smuggling route to Mayotte, part of the Comoros archipelago in the Indian Ocean and the poorest French overseas department.

The roots of human-smuggling to Mayotte date back to 1975, when the Union of the Comoros gained independence, but Mayotte voted to remain French. Since then – and fuelled by ongoing diplomatic conflict – France has imposed ever more restrictive immigration controls that have disrupted long-standing, often circular, migration trends based on cultural and ethnic ties. This situation, together with the higher standard of living in Mayotte, has driven many Comorian migrants to seek the services of human smugglers to reach the French department.

Mayotte has also become increasingly attractive to Malagasy and Central African migrants and refugees, with authorities reporting a spike in asylum claims by Central African nationals in 2019.1 The increase on this route is partly as a consequence of the ‘northern route’ to Europe through Libya turning more hazardous. These continental African migrants employ human smugglers to reach Mayotte, where they hope to obtain visas or asylum status, and thereby gain legal access to Europe.

Fears of the coronavirus, however, brought an almost complete stop to typical migration flows during several weeks at the onset of the crisis. The impact of the coronavirus on smuggling routes to Mayotte – including the temporary reduction in human smuggling following border closures, the almost complete disruption of air-smuggling routes, and the use of smugglers by migrants wishing to return home – exemplifies the regional trends explored in the April 2020 GI-TOC policy brief titled ‘Smuggling in the time of Covid-19’.2

Human smuggling between Anjouan and Mayotte

Every year, between 22 000 and 25 000 people are smuggled across the 70-kilometre stretch of sea that separates Anjouan, the main island in the Comoros archipelago, and Mayotte.3 NGOs working in Mayotte note that the number of migrants using this route has been increasing year on year.

Smugglers take circuitous routes to evade authorities, typically travel at night and often overload their kwassa kwassa (small fishing boats used to transport migrants). The short crossing is consequently extremely dangerous, with the French Senate estimating that 7 000 to 10 000 Comorians died making this journey irregularly between 1995 and 2012.4 Unofficial estimates, as well as statements made by Comorian authorities, suggest the figure is far higher.5 In 2015, Anissi Chamsidine, the governor of Anjouan, publicly stated that as many as 50 000 had died, labelling the thin channel between the islands ‘the world’s largest marine cemetery’.6

The coronavirus pandemic, and the prevalence of the virus on Mayotte in particular, significantly disrupted this pattern of movement. COVID-19 was perceived to hit Mayotte first – by 30 April, when the Union of the Comoros announced its first cases,7 Mayotte had already reported 460 cases.8 In an attempt to limit contagion, Comoros closed its borders on 23 March; an unprecedented move that disrupted not only informal crossings, but also the large number of deportations from Mayotte. It also triggered a temporary lull, and partial reversal, in the long-standing smuggling flow from Anjouan to Mayotte. Between 15 March and 6 April, authorities in Mayotte detected no arrivals of kwassa from the Comoros,9 although Andry Rakotondravola, editor-in-chief for radio production at Mayotte Premier, suggests that irregular crossings continued, albeit in drastically smaller numbers.

Placard in Moroni, the capital of Comoros, stating ‘Mayotte is Comorian and will remain so forever’.

© GI-TOC

Locally constructed fishing boats, known as ‘kwassa kwassa’, docked in the port of Moroni, Comoros.

© GI-TOC

According to the GI-TOC’s research, this decrease can be attributed to enhanced surveillance by authorities in Mayotte and Comoros, as well as reduced demand due to fears of contracting the virus in Mayotte. French naval patrols have been turning back any migrant vessels they intercept en route to Mayotte, rather than the typical practice of detaining the migrants onshore. Additionally, Comorian law-enforcement officials have been closely monitoring known disembarkation points across the coast of Anjouan to prevent smugglers returning with migrants from Mayotte, whom authorities fear may be infected with the virus. This enhanced vigilance marks a significant shift from Comoros’ typically lax position on irregular emigration, and puts the country’s authorities in the awkward position of policing a national border they do not officially recognize.

The suspension of deportations from Mayotte also drove a new need for human-smuggling services. In March and April, Comorian authorities intercepted a small number of smugglers returning with Comorians who were fleeing the virus in Mayotte.10 This situation marked a reversal in typical human-smuggling patterns: prior to the outbreak of the pandemic, Comorian migrants only risked using human smugglers for the outward journey to Mayotte. (Many Comorians return home after a period in Mayotte, and typically effect their homeward journey by presenting themselves to the Mayotte authorities to be deported.) The closure of the Comoros border, and consequent suspension of deportations, meant that Comorians were forced to hire smugglers to facilitate their journey home; a trend that has been seen across southern and East Africa since the pandemic reached the region.11

Migrants in search of healthcare

The lull in Comorians travelling to Mayotte, and the small reverse flow in migration, proved to be only temporary. From 6 April, French authorities began tracking a sharp rise in the number of kwassa arriving in Mayotte, and by 20 April arrivals had reportedly returned to normal levels for that time of year.12

Since early June, however, Julien Kerdoncuf – the sub-prefect of Mayotte and coordinator of the response to the coronavirus crisis – has noted a surge beyond pre-pandemic levels in Comorians arriving irregularly, many of whom are in urgent need of medical attention. The disruption to human movement to Mayotte caused by the pandemic interrupted the long-standing practice of Comorians seeking medical treatment on the island. Having been forced to wait in Comoros for weeks, many are now arriving in Mayotte in dire condition.

While benefiting from a higher standard of medical care than Comoros, Mayotte nonetheless has scarce health resources compared to the rest of France, with only 80.7 doctors per 100 000 inhabitants in 2019.13 The coronavirus pandemic, together with the dengue fever epidemic currently sweeping across Mayotte, is heightening fears among impoverished communities in Mayotte that increasing numbers of migrants will compromise their ability to access medical treatment.14

Disrupted movement of Central African migrants to Mayotte

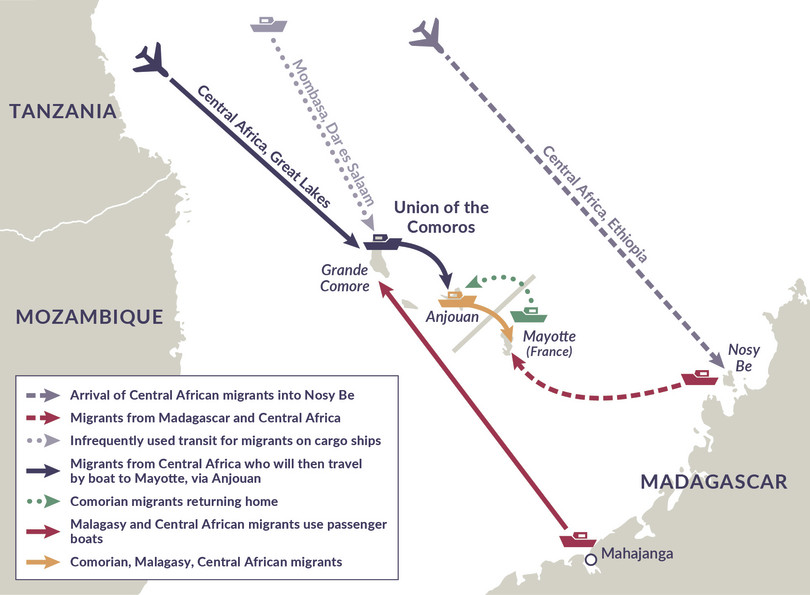

Prior to the pandemic, most migrants from Central Africa flew from their country of origin to the Comorian capital of Moroni, where they could obtain a tourist visa. They then travelled via legal channels to Anjouan, where they employed the services of smugglers to travel onward to Mayotte.

A far smaller but growing number of continental African migrants flew to Madagascar, taking advantage of a similarly generous tourist visa regime. From Madagascar, there were two principal routes by which Malagasy and Central African migrants reached Mayotte: travelling by regular passenger boat from Mahajanga (on the west coast of Madagascar) to Moroni, from where they were brought by smugglers to Mayotte; or hiring human smugglers to travel by kwassa from Nosy Be, an island off the northwest coast of Madagascar, directly to Mayotte. The rough seas, long journey times (24–30 hours), night-time departures and use of small kwassa make the journey between Nosy Be and Mayotte even more hazardous than that between Anjouan and Mayotte. Local radio director Rakotondravola notes that capsizing is common, with one boat full of migrants sinking off the coast of Nosy Be in January.

Daniel Silva y Poveda, Chief of Mission for the International Organization for Migration Mission to Madagascar and the Union of the Comoros, attributes a 2019 spike in Central African migrants travelling from Nosy Be to the opening of a direct Ethiopian Airways flight from Addis Ababa to the island.15

Figure 3 Shifting dynamics of human-smuggling routes to Mayotte.

Since March, the almost complete suspension of commercial flights due to the coronavirus pandemic has rendered air travel from Central Africa to Comoros or Madagascar impossible. Authorities in Mayotte have recorded only two arrivals of kwassa carrying Central African migrants from Madagascar since 20 March.16

Some African migrants who would previously have flown to Comoros or Madagascar may instead resort to overland routes to Mozambique or Tanzania, which are far more dangerous. In addition, the movement restrictions imposed to tackle the coronavirus have made such overland travel even riskier, as smugglers seeking to evade increased border controls use longer, more hazardous routes and more dangerous transport methods. In particular, movement restrictions have accelerated the trend of smugglers disguising migrants in commercial vehicles, which are permitted to cross borders. This tactic was used by smugglers moving migrants into Mozambique from Malawi in late March 2020, with tragic consequences. Mozambique immigration authorities at the border discovered the bodies of 64 Ethiopian migrants who had asphyxiated in a lorry container, along with 14 survivors.17

Migrants who successfully reach East Africa’s coastal states on their journey to Mayotte would then need to cross the Mozambique Channel. In a pre-existing but little utilized and risky route, smugglers transport migrants on cargo vessels from Mombasa or Dar es Salaam to Moroni. According to Daniel Silva, these routes may increase in popularity due to the suspension of air travel.18

Figure 4 Migration to and deportations from Mayotte.

SOURCE: Préfet de Mayotte (Operation Shikandra 2019 official statistics, and as reported in Le Journal de Mayotte in February 2020)

Looking forward

As of early June, the smuggling of Comorians to Mayotte has resumed, with arrivals reportedly exceeding pre-pandemic levels. Although ongoing disruption of air travel has resulted in fewer arrivals of Malagasy and Central African migrants in Mayotte, this is also likely to be only a temporary reduction, lasting only as long as the suspension of flights.

The pandemic has not changed the underlying drivers of human movement. If anything, vanishing livelihoods in the wake of the pandemic are likely to drive migration. Already irregular migration to Mayotte is reportedly exceeding pre-pandemic levels. Once controls on movement are relaxed and fear of the virus diminishes, numbers may increase further. This is in line with the GI-TOC’s predictions with respect to human-smuggling trends across the region, as well as globally.19

For migrants, both in transit and in irregular status at destination, growing anti-migrant sentiment, prolonged irregularity, and riskier journeys are swelling protection risks. The human-smuggling industry appears set to become yet more pivotal to migration mechanics in the post-pandemic landscape.

Notes

-

Anne Perzo, Forte hausse des demandes d’asile: interview du directeur de l’OFPRA en mission à Mayotte, 20 September 2019, Le Journal de Mayotte, https://lejournaldemayotte.yt/2019/09/20/forte-hausse-des-demandes-dasile-interview-du-directeur-de-lofpra-en-mission-a-mayotte/ ↩

-

Lucia Bird, Smuggling in the time of Covid-19: The impact of the pandemic on human-smuggling dynamics and migrant-protection risks, The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, April 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/smuggling-covid-19/. ↩

-

Interview with Julien Kerdoncuf, Prefecture de Mayotte, 9 June 2020. ↩

-

Sénat, Rapport D’information Fait au nom de la commission des lois constitutionnelles, de législation, du suffrage universel, du Règlement et d’administration générale à la suite d’une mission effectuée à Mayotte du 11 au 15 mars 2012, July 2012, https://www.senat.fr/rap/r11-675/r11-6751.pdf. ↩

-

Al Jazeera, Island of Death, 3 February 2016, https://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/aljazeeraworld/2016/02/island-death-160203115053532.html; Edward Carver, Mayotte: the French migration frontline you’ve never heard of, The New Humanitarian, 14 February 2018, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/feature/2018/02/14/mayotte-french-migration-frontline-you-ve-never-heard. ↩

-

Elise Wicker, France’s migrant ‘cemetery’ in Africa, BBC World Service, 19 October 2015, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-34548270. ↩

-

Al Jazeera, Comoros verifies first confirmed coronavirus case, 30 April 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/comoros-verifies-confirmed-coronavirus-case-200430155748926.html; WHO Health Emergency Dashboard, Covid-19, Comoros, https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/km. ↩

-

WHO Health Emergency Dashboard, Covid-19, Mayotte, https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/yt. ↩

-

Interview with Julien Kerdoncuf, Prefecture de Mayotte, 9 June 2020. ↩

-

Bruno Minas, 6 personnes en provenance de Mayotte ont été arrêtées ce lundi matin à Domoni par les gendarmes comoriens, leur Kwassa a été détruit, Radio France, 30 March 2020, https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/mayotte/6-personnes-provenance-mayotte-ont-ete-arretees-ce-lundi-matin-domoni-gendarmes-comoriens-leur-kwassa-ete-detruit-817886.html. ↩

-

Lucia Bird, Smuggling in the time of Covid-19: The impact of the pandemic on human-smuggling dynamics and migrant-protection risks, The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, April 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/smuggling-covid-19/. ↩

-

Interview with Julien Kerdoncuf, Prefecture de Mayotte, 9 June 2020. ↩

-

Ouest France, À Mayotte, l’épidémie de dengue s’ajoute au coronavirus, 7 May 2020, https://www.ouest-france.fr/mayotte/mayotte-l-epidemie-de-dengue-s-ajoute-au-coronavirus-6827943. ↩

-

Ouest France, À Mayotte, des entraves au secours de malades provenant des Comores inquiètent l’ARS, 9 June 2020, https://www.ouest-france.fr/sante/virus/coronavirus/mayotte-des-entraves-au-secours-de-malades-provenant-des-comores-inquietent-l-ars-6863310. ↩

-

Interview with Daniel Silva y Poveda, Chief of Mission for the International Organization for Migration Mission to Madagascar and the Union of the Comoros, 5 June 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Interview with Julien Kerdoncuf, Prefecture de Mayotte, 9 June 2020. ↩

-

The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, Civil Society Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin, Issue 6, March–April 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/esaobs-risk-bulletin-6/. ↩

-

Interview with Daniel Silva y Poveda, Chief of Mission for the International Organization for Migration Mission to Madagascar and the Union of the Comoros, 5 June 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Lucia Bird, Smuggling in the time of Covid-19: The impact of the pandemic on human-smuggling dynamics and migrant-protection risks, The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, April 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/smuggling-covid-19/. ↩