Somalia’s khat ban has led to the emergence of a contraband industry.

In response to the coronavirus pandemic, on 18 March the Somali Federal Government suspended all international commercial flights into and out of the country. Accompanying this measure was a temporary suspension of imports of khat leaf, a mild amphetamine-like stimulant typically consumed by men during lengthy communal chewing sessions. Somalia’s numerous autonomous regional administrations soon followed with bans of their own.

Although numerous medical hazards have been attributed to the drug (it is illegal in most developed countries),1 the rationale for its recent ban in Somalia stemmed from fears that khat could become a vector for the transmission of the coronavirus. The fact that khat leaf is picked, packed and transported by hand – as well as the social manner in which it is consumed – led Somali authorities to conclude that the health risks outweighed the significant tax revenue derived from the trade.

Miraa and hareeri

Growing conditions in Somalia are largely too hot and arid for the water-intensive crop, and consequently almost all the khat consumed in Somalia is imported from the highlands of Kenya and Ethiopia. Kenyan khat (known as miraa) is far more coveted than the Ethiopian variety (known as hareeri). Khat has a short shelf life, completely losing its potency within two days of being harvested, rendering the khat economy extremely sensitive to disruptions in the supply chain.

Mogadishu, where approximately one-quarter of the country’s population resides, is by far the largest market for khat consumption. On average, 50 tonnes of miraa are exported daily from Kenya to Mogadishu, with a retail value of approximately US$1 million.2 Kenyan miraa farmers – who rely on dozens of daily flights from Nairobi to deliver their product to Somalia – have been particularly hard hit by the ban on the drug.

Ethiopian hareeri is most popular in the northern breakaway republic of Somaliland. Hareeri largely enters Somalia across land borders, due to its closer proximity to the khat-growing regions in Ethiopia as well as its more developed road infrastructure. Consequently, the hareeri supply chain has been significantly more insulated from suspended commercial air transport.

Soaring prices

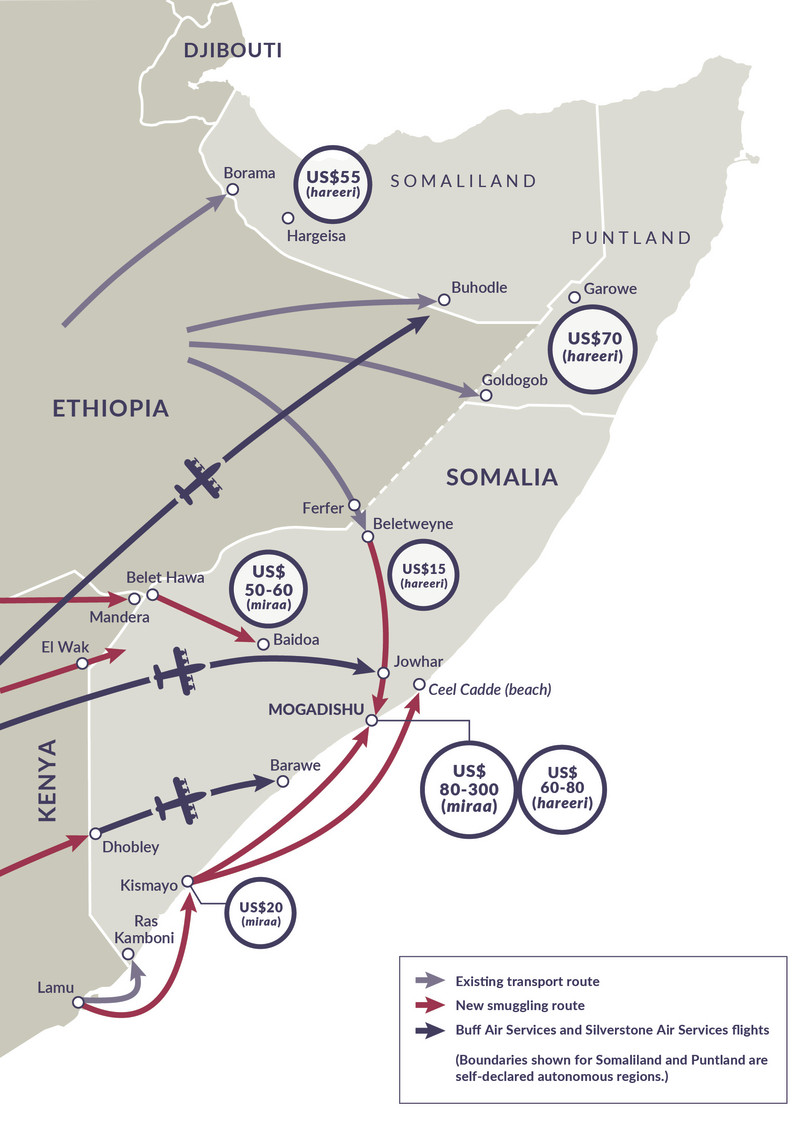

Kenyan miraa typically sold for US$20–US$25 per kilogram before the ban, but prices have since skyrocketed. In early April 2020, soon after the ban came into effect, Reuters news agency reported that one kilogram in Mogadishu fetched as much as US$300.3 However, GI-TOC research indicates that that prices had stabilized at between US$80 and US$120 as of early June 2020, depending on the freshness of the khat leaf. The drastic drop in price since the early days of the khat ban might signal the normalization of the illicit trade as smuggling routes and modalities become better established.

Regional administrations have also seen spikes in price, albeit less drastic. In Somaliland, Ethiopian hareeri khat that once fetched US$35 a kilogram reached a price of US$55 during the ban.4 In Puntland, Somalia’s northernmost regional administration, prices jumped to US$70 per kilogram.5 In Kenya’s capital of Nairobi, conversely, miraa prices have fallen as a result of the glut in supply caused by the Somali ban. The prices for some varieties of the drug have dipped by a third, or even halved.6

The creation of a contraband industry

Ethiopian khat (hareeri) in Beletweyne, a major entry and distribution point for the drug during the ban, June 2020.

© GI-TOC

To circumvent the new restrictions, a number of land and sea smuggling routes have emerged, while some existing routes have seen far higher volumes. Existing small-scale sea transport routes from northern Kenya into southern Somalia have expanded to reach the port city of Kismayo, as well as pushing onward to Mogadishu itself. According to the GI-TOC’s information, the primary entry points for seaborne khat are Mogadishu’s Jazeera beach and Ceel Cadde beach, which is located some 100 kilometres north-east of the capital.7 One Somali journalist told the GI-TOC that khat smugglers commonly conceal the leaf within containers marked as medical supplies.8

The ban has also caused importers and consumers to increasingly shift away from miraa towards the cheaper Ethiopian hareeri khat, the distribution of which has been less disrupted by the suspension of commercial flights. The town of Beletweyne, near the border with Ethiopia, has become a hub for the import and onward distribution of hareeri. As of early June, Beletweyne sees an average of 6 tonnes of hareeri transit through the city each day – before the ban, imports from Ethiopia were minimal.9 The retail price of the drug in the town has remained relatively stable at US$15 per kilogram, suggesting an elastic supply that has quickly scaled up to meet the increased demand. From Beletweyne, much of the cargo proceeds onwards to Mogadishu, a supply route that has only emerged as a result of the cessation of Kenyan khat flights to the capital.

Transporting the leaf by road is not without its perils. The Islamist militant group Al-Shabaab, which controls much of Somalia’s hinterland, is likely to execute any driver caught transporting the drug. It is therefore no surprise that hareeri transported from Beletweyne fetches exorbitant prices in Mogadishu – between US$60 and US$80 per kilogram.10

Figure 1 Transport routes used to circumvent Somalia’s khat ban, and local prices per kilogram under the ban.

SOURCE: GI-TOC/ Rift Valley Institute

Smuggling by air

Some air carriers have continued to operate in Somalia under special licences authorizing them to transport COVID-19 medical supplies and other necessities. On least three occasions, Kenya-registered aircraft have been found with shipments of khat concealed among medical supplies destined for Somalia.

On 26 May 2020, a flight operated by Silverstone Air Services delivered an illicit shipment of khat to Jowhar, the capital of the regional administration of HirShabelle. The shipment was received by the HirShabelle police commissioner before being transferred to two lorries destined for Mogadishu.11 While being escorted by Somali National Army and HirShabelle police vehicles, the convoy hit a roadside IED planted by Al-Shabaab militants approximately 60 kilometres north of Mogadishu. Nine soldiers were killed and four others injured.12

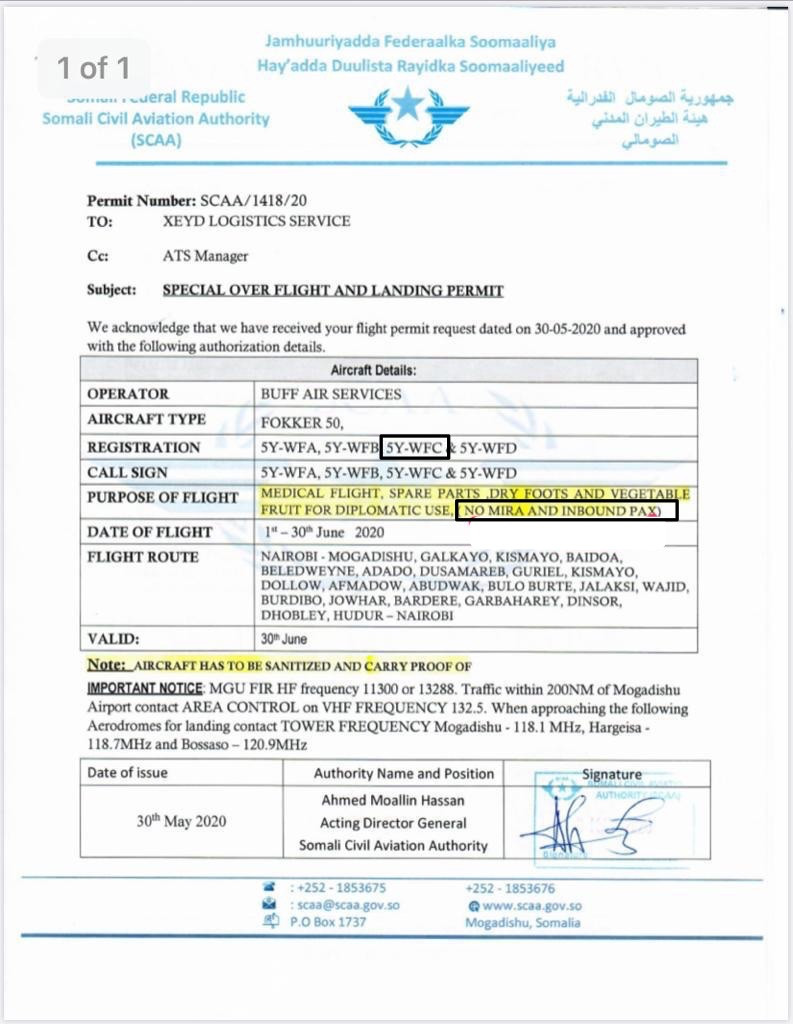

Five days later, an aircraft registered to Buff Air Services, was recorded delivering a shipment of khat in the northern town of Buhodle, on the border with Ethiopia. On 1 June, the Somali Federal Government suspended the operation licences of both Buff Air Services and Silverstone Air Services.13

On 19 June, a Silverstone-registered aircraft, leased to Mogadishu-based Maandeeq Air Logistics, was reported to have again transported a cargo of miraa concealed as medical supplies from the town of Dhobley, on the Somalia–Kenya border, to the southern littoral town of Barawe.14 Silverstone Air Services, Buff Air Services, and Maandeeq Air Logistics did not respond for comment.

Buff Air Services (registration 5Y-WFC) offloading miraa at Buhodle airstrip, 31 May 2020.

SOURCE: Social media

Buff Air Services’ June 2020 special operation licence, which specified that no passengers or Kenyan khat (miraa) were permitted on flights. The licence was cancelled on 1 June 2020, following a shipment of Kenyan khat to Buhodle airstrip aboard aircraft 5Y-WFC.

© GI-TOC

Silverstone Air Services/Maandeeq Air Logistics aircraft (5Y-SMS) on the apron at Dhobley airport with boxes of smuggled khat, 19 June 2020. On one box is scrawled ‘COVID aid’.

© Harun Maruf

Tokenistic enforcement

On 24 March 2020, the federal aviation minister publicly burned 40 kilograms of khat in a largely symbolic gesture accompanying the government’s announcement of the khat ban.15 Other ‘khat burnings’ have taken place across Somalia, most notably in Somaliland, where seizures in over five towns across the region were put to the torch.16 Smuggling routes have also been targeted: on 10 May, Somali federal police arrested a number of suspected illegal traders who had allegedly smuggled khat into Mogadishu by sea, while on 4 June, the Coast Guard seized a consignment of khat concealed in a fishing boat and subsequently burned the cargo.17

But aside from these public displays and arrests, enforcement of the khat ban has been piecemeal and largely tokenistic. As the legal custodian of Somalia’s airspace, it has been a relatively simple matter for the Somali Federal Government to suspend international air traffic. But with little ability to enforce its edicts outside of Mogadishu, stymying the land-based trade in the drug has proven a more difficult challenge, especially given that a large segment of the population is physically dependent on the drug. Enforcement of the ban has also been made difficult due to the fact that the security forces themselves are likely receiving bribes from khat smugglers.18

An unsustainable ban

Taxes levied on khat are an important source of revenue for the Somali Federal Government and are vital for regional authorities. In 2019, taxes on khat brought through Mogadishu airport raised US$16.6 million for the Somali Federal Government, making up about 15% of total customs and import duties and 5% of all federal revenue.19 In Somaliland, taxes on khat account for 30% of all revenue for the administration, or about US$35 million annually.20

At the household level, Somali women heavily rely on the income generated by the khat trade: while consumers of khat are predominantly men, the market sellers are almost entirely women. One khat seller in Mogadishu, a mother of six, told the GI-TOC that khat was the only source of income for her family, and the ban had left her unable to pay her rent or medical bills. ‘I personally appeal to the Federal Government with the strongest voice to ease the ban so that we can feed our children,’ she said.21

Despite spikes in COVID-19 cases, both the Somaliland and Puntland administrations ended their respective bans on khat prior to Eid al-Fitr (23 May 2020), the celebration marking the end of Ramadan. At the time of writing, the khat ban remains in place in southern Somalia. It is unclear, however, how much longer the Somali Federal Government will be able to maintain it. Drug bans are notoriously hard to enforce even in developed countries – in the case of a highly fragile state like Somalia, it will likely prove an impossible task. In addition, the ban deprives an impoverished state of a significant revenue source that could be directed towards mitigating the impact of the coronavirus crisis.

Moreover, signs that the security forces may already be involved in the illicit khat trade are worrying. Should the ban continue for a protracted period, there is a risk that the nascent criminal networks (including members of the police and army) which are currently facilitating the illicit trade will become entrenched. When the ban is eventually lifted, these networks may continue to operate, circumventing government taxation of khat imports. Land and sea smuggling routes developed during the coronavirus crisis may become permanent.

Notes

-

For a discussion of the medical risks associated with khat consumption, see Ahmed Al-Motarreb, Molham Al-Habori and Kenneth J Broadley, Khat chewing, cardiovascular diseases and other internal medical problems: The current situation and directions for future research, Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 132, 3, 540–548. ↩

-

Abdi Sheikh, Wives rejoice and traders despair as coronavirus halts khat supply to Somalia, Reuters, 2 April 2020, https://af.reuters.com/article/idAFKBN21K1JO-OZATP. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Sahra Ahmed Koshin, Khat and COVID-19: Somalia’s cross-border economy in the time of coronavirus, Rift Valley Institute, May 2020, http://riftvalley.net/sites/default/files/publication-documents/Khat%20and%20COVID-19%20by%20Sahra%20Ahmed%20Koshin%20-%20RVI%20X-border%20Project%20%282020%29.pdf. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interviews with four khat users in Nairobi, 14–15 June 2020. ↩

-

Information provided by a researcher in Mogadishu. ↩

-

Interview with a Somali journalist, 1 June 2020. ↩

-

Information provided by a researcher in Mogadishu. ↩

-

Interview with a khat merchant in Mogadishu, 16 June 2020. ↩

-

Information provided by a researcher in Mogadishu. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Goobjoog News, Illegal khat transport costs two Kenyan airlines licenses in Somalia, 2 June 2020, http://goobjoog.com/english/illegal-khat-transport-costs-two-kenyan-airlines-license-in-somalia/; and Garowe Online, Somalia revokes licenses for Kenyan airlines over alleged smuggling of khat, 1 June 2020, https://www.garoweonline.com/en/news/somalia/somalia-revokes-licenses-for-kenyan-airlines-over-alleged-smuggling-of-khat. ↩

-

Harun Maruf, ‘Hearing reports that a plane carrying boxes…,’ Twitter post, 11.15 p.m., 19 June 2020, https://twitter.com/HarunMaruf/status/1274073309999706114. An airport worker in Dhobley confirmed the report to GI-TOC on 25 June 2020. ↩

-

Amanda Sperber and Abdalle Ahmed Mumin, Khat traders, farmers take a hit amid coronavirus pandemic, Al Jazeera, 31 Mar 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/ajimpact/khat-traders-farmers-hit-coronavirus-pandemic-200331064458024.html. ↩

-

MENAFN, Somaliland: Khat chewing goes covert as state implements import ban, 2 May 2020, https://menafn.com/1100107047/Somaliland-Khat-Chewing-goes-Covert-as-State-Implements-Import-Ban. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Information provided by a researcher in Mogadishu. ↩

-

Federal Government of Somalia, Revenue Performance Report as of December 2019, internal report obtained by the GI-TOC. ↩

-

Sahra Ahmed Koshin, Khat and COVID-19: Somalia’s cross-border economy in the time of coronavirus, Rift Valley Institute, May 2020, http://riftvalley.net/sites/default/files/publication-documents/Khat%20and%20COVID-19%20by%20Sahra%20Ahmed%20Koshin%20-%20RVI%20X-border%20Project%20%282020%29.pdf. ↩

-

Interview with female khat merchant, Mogadishu, 6 June 2020. ↩