In Somalia, COVID-19 opens up new avenues for corruption.

Preparations for the emergency response to the coronavirus outbreak were already underway prior to Somalia confirming its first case on 16 March 2020. Since then, the level of external support has been unprecedented. On 24 March, Somalia received its first donation of medical supplies and protective equipment, including 100 000 face masks, from the Jack Ma Foundation.1 Following Jack Ma’s lead in ‘mask diplomacy’, multiple donors – including the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Qatar and even neighbouring Ethiopia – have scrambled to airlift medical supplies in bulk to Somalia. Photos of officials receiving the donations have been routinely posted on Somali government websites and social-media accounts in appreciation.

But the rapid influx of international donations intended to prop up a weak healthcare sector has also presented new opportunities for self-enrichment among corrupt officials. While progress has been made in public financial management, Somalia remained at the bottom of Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index in 2019. An April investigation into the apparent systemic misappropriation of donor funds (allocated pre-COVID-19) by multiple government officials, including representatives of the Federal Ministry of Health, demonstrates that corruption remains widespread. GI-TOC research has confirmed that supplies donated to tackle the coronavirus outbreak have also been misappropriated for private gain.

A healthcare system in crisis

Somalia is among the least-prepared countries when it comes to managing the outbreak of a highly infectious disease. An estimated 2.6 million internally displaced persons reside in more than 2 000 mostly squalid informal settlements throughout the country; 4.1 million people are categorized as food insecure; and at least 1 million children are thought to be malnourished.2 The country has the second-highest mortality rate attributed to unsafe water, unsafe sanitation and a lack of hygiene (after Chad), and among the lowest ratios of physicians to population in the world.3 When the coronavirus arrived, the country was already facing severe flooding along its rivers, prompting fears of outbreaks of cholera and watery diarrhoea, and the worst desert locust infestation in recent history.

A May 2020 report co-published by the Heritage Institute for Policy Studies (HIPS) – a Somali think-tank – and City University of Mogadishu (CU) paints a grim picture of the state of the healthcare system. According to the report, both public and private services are ‘ill equipped to meet even the primary health service needs of the bulk of the population’.4 The report lists donor dependence and an absence of government oversight as two of several major challenges even before the coronavirus outbreak. Data aggregating external aid to Somalia between 2018 and 2020 reveals that more than US$330 million had been disbursed throughout the country targeting the health sector.5 (The Federal Ministry of Health was allocated a little over US$9.3 million in the 2020 budget.) The HIPS/CU report also lists the domination of ‘unaffordable and substandard’ private-sector services as a major challenge, though it concedes that in the almost total absence of public-health facilities, the private sector remains a ‘critical healthcare player’, despite the lack of regulation.6

Corruption within the Federal Ministry of Health?

On 25 March 2020 – the day before the second case of coronavirus was confirmed in Somalia – Kasim Ahmed Jimale, the international health regulations national focal point of the Federal Ministry of Health, announced his resignation after almost 10 years of service.7 The timing of his resignation prompted speculation on Somali social media over the state of affairs in the Ministry of Health. GI-TOC sources in Mogadishu assert that he left the ministry amid a burgeoning corruption scandal, and subsequently informed officials in the office of the prime minister of what he had uncovered.

On the night of 4 April, Mohamud Mohamed Bulle, the director of administration and finance for the Ministry of Health, was arrested and detained by police.8 On 6 April, the director general at the ministry was also arrested and detained.9 Somalia media outlets, and subsequently a Foreign Policy article,10 cited the alleged misappropriation of COVID-19 donations as the reason for the arrests. However, the GI-TOC’s sources in Mogadishu, who are close to the investigation, suspect that corruption had been going on for years before the outbreak of the pandemic.

On the morning of 4 April, following a tip-off, Somali security forces raided a compound in central Mogadishu and seized a large volume of materials used to mass produce falsified accounting paperwork, including invoice books, receipt books and more than 60 fake stamps for commercial companies. According to the GI-TOC sources, the paperwork was used to falsely demonstrate the supply of goods and services to government ministries that had been paid for with international donor funds (allocated prior to the COVID-19 pandemic), while in fact government officials were diverting the funds for private use.

On 27 April, a letter from the federal office of the auditor general was sent to various development partners notifying them of a ‘forensic audit’ underway in the Ministry of Health to investigate the suspected fraud scheme that had diverted donor funds. The audit would cover, among others, funds allocated for medical supplies, medical equipment, office supplies and equipment, conference facilities and air ticketing.11 The director general and director of administration and finance of the Ministry of Health were both listed in the letter as having been arrested in connection with the scheme which, it suggested, may have been going on for several years and likely involved several other government institutions.

The actions taken by the auditor general against the individuals suspected to be involved in the scheme may well represent a positive step in addressing an entrenched culture of impunity among government officials in Somalia. Several GI-TOC sources have indicated, however, that the unprecedented step of launching a public investigation into government officials for the misappropriation of donor funds at that time may also have been intended to justify the transfer of managing the coronavirus response from the Ministry of Health. On 28 March – after the resignation of Jimale, but before the raid on the compound and arrest of his former colleagues – a letter from the permanent secretary to the prime minister informed the UN that two colleagues within the prime minister’s office would serve as focal points ‘responsible for coordinating all assistance related to Covid-19’ on behalf of a national coordination committee.12

Diversion of donor assistance

Consignment of medical supplies, including items purchased by the local business community, unloaded at Adado airport in Galmudug State, 26 May 2020.

SOURCE: Social media

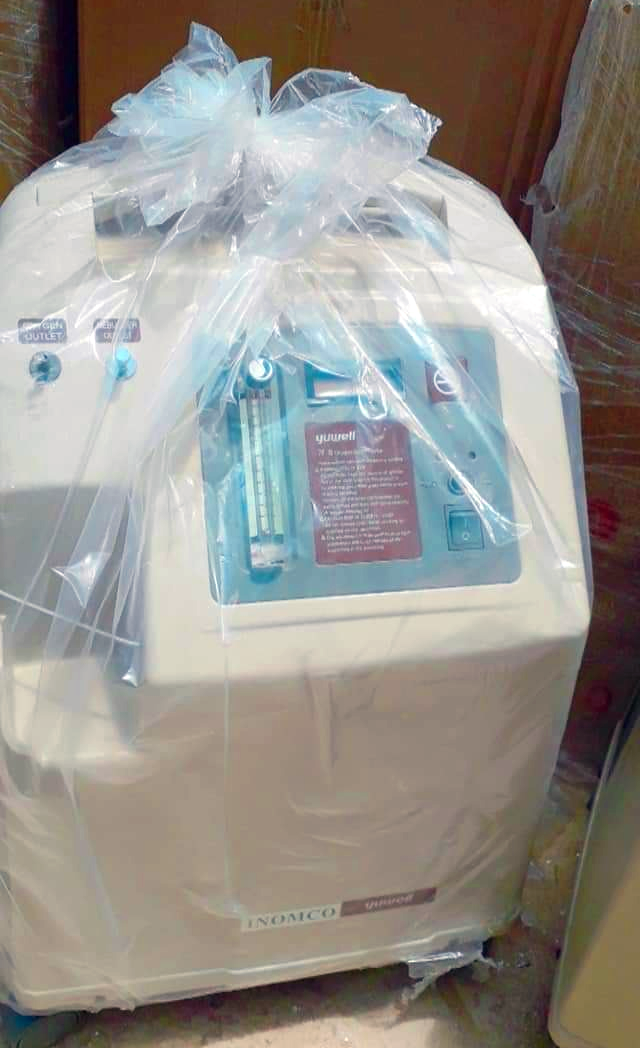

An oxygen concentrator, reportedly purchased at a private pharmacy in Mogadishu by Galmudug-based businessmen.

© GI-TOC

A lack of transparency over the management and distribution of some donor assistance has fuelled concerns regarding the diversion of medical supplies. The GI-TOC has been able to establish that some COVID-19 supplies donated by international partners have been diverted by officials tasked with coordinating and managing the response for private gain.

In late April, when asked by a GI-TOC source about the diversion of donated items, an official within the Federal Government response coordination structure confirmed the disappearance of many items donated by Jack Ma (received on 24 March) and the UAE (on 14 April). This assertion was supported by former Somali president Sheikh Sharif Ahmed’s statement on 25 May that medical aid had found its way to markets in Mogadishu.13

On 27 May, medical supplies were flown to Adado, a town in the regional Galmudug State, to equip the local hospital. According to multiple independent GI-TOC sources, the consignment included some international donations distributed by the Federal Government to Galmudug State. However, additional supplies donated by international partners — including an oxygen concentrator — had been purchased by the Galmudug business community from markets in Mogadishu.14 A dedicated Adado COVID-19 social media account praised several Galmudug businessmen for their donations, including a ventilator, to the hospital.15

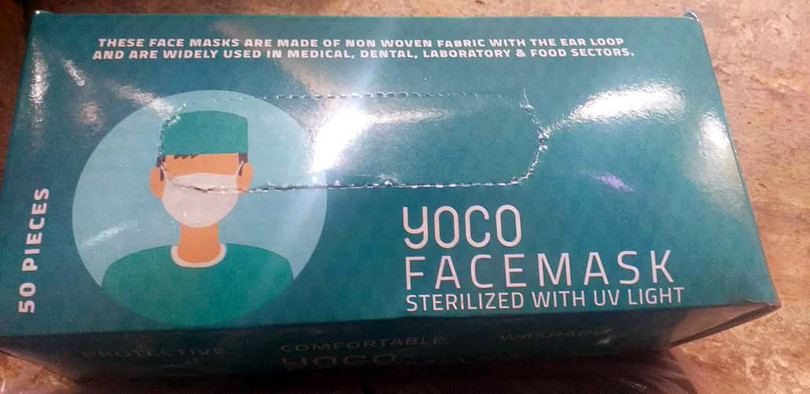

On 3 June, images of what appeared to be donated items adorned with the flags of Qatar and Turkey (including soap, hand sanitizer and breathing aids) available for purchase in a Mogadishu pharmacy were widely shared on social media and subsequently published on several Somali news websites.16 According to the GI-TOC sources, National Intelligence and Security Agency agents were subsequently deployed to remove any further evidence of the goods in marketplaces in Mogadishu. The GI-TOC, however, subsequently found evidence of donated items – particularly face masks – for sale in pharmacies throughout the city.17 One GI-TOC source claimed that a consignment of face masks earmarked for a regional Somali administration had even been returned to Mogadishu, from where it then found its way to pharmacy shelves.18

Undermining the coronavirus response

An extraordinary effort, involving numerous government institutions, non-government institutions and external partners, is being made to stem the coronavirus crisis in Somalia. Considering the formidable healthcare challenges facing Somalia, the response to date has been remarkable and will likely have already saved many lives.

However, the recent exposure of a suspected criminal network involving the Ministry of Health indicates the extent to which a culture of corruption remains pervasive within Somalia and how international aid remains susceptible to misappropriation. The rapid influx of sorely needed medical supplies has presented new opportunities for self-enrichment, which some public servants have clearly exploited.

Left: Face masks photographed by the GI-TOC in a pharmacy in Mogadishu, 18 June 2020. Right: Medical donations to the Somali government, including boxes of face masks identical to those documented by the GI-TOC, alongside aid from Turkey and China, 28 May 2020.

SOURCES: © GI-TOC & Social media

Notes

-

The Jack Ma Foundation was founded by Chinese businessman Jack Ma, the co-founder and chairman of Alibaba Group. As of late June 2020, the Jack Ma Foundation had made three rounds of donations of medical equipment and supplies to all 54 states on the African continent. ↩

-

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Humanitarian Bulletin: Somalia 1 May–2 June 2020, https://www.unocha.org/somalia. ↩

-

World Health Organization, Global Health Observatory Data Repository, https://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main. ↩

-

Ali A Warsame, Somalia’s Healthcare System: A baseline study & human capital development strategy, Heritage Institute for Policy Studies and City University of Mogadishu, May 2020, http://www.heritageinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Somalia-Healthcare-System-A-Baseline-Study-and-Human-Capital-Development-Strategy.pdf. ↩

-

Federal Republic of Somalia, Aid Flows in Somalia: Analysis of Aid Flow Data, April 2020, https://somalia.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/Aid%20Flows%20in%20Somalia%20-%202020.pdf. The Federal Ministry of Health has been both the recipient and implementing agency for many external donor projects. ↩

-

Ali A Warsame, Somalia’s Healthcare System: A baseline study & human capital development strategy, Heritage Institute for Policy Studies and City University of Mogadishu, May 2020, http://www.heritageinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Somalia-Healthcare-System-A-Baseline-Study-and-Human-Capital-Development-Strategy.pdf. A 2015 Al Jazeera investigation found that many private clinics and pharmacies were dispensing counterfeit and expired medicines. Hamza Mohamed, Counterfeit medicine endangering Somali lives, Al Jazeera, 3 July 2015, https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2015/06/counterfeit-medicine-endangering-somali-lives-150625100645962.html. ↩

-

Kasim Ahmed Jimale, ‘To night I have decided to resign…’, Twitter post, 8.04 p.m., 25 March 2020, https://twitter.com/KJimale/status/1242905163922321409. ↩

-

Abdi Weriye Ahmed, Sarkaal ka tirsan Wasaaradda Caafimaad oo lagu xiray Muqdisho, kaddib markii lala xiriiriyay, HalQaran News, 5 April 2020, https://www.halqaran.com/index.php/2020/04/05/sarkaal-ka-tirsan-wasaaradda-caafimaad-oo-lagu-xiray-muqdisho-kaddib-markii-lala-xiriiriyay/. ↩

-

Radio Dalsan, Agaasime kale oo ka tirsan Wasaaradda Caafimaadka oo la xiray, 6 April 2020, https://www.radiodalsan.com/agaasime-kale-oo-ka-tirsan-wasaaradda-caafimaadka-oo-la-xiray/. ↩

-

Subban Jama and Ayan Abdullahi, ‘We Are Used to a Virus Called Bombs’, Foreign Policy, 12 May 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/12/coronavirus-pandemic-somalia-al-shabab/. ↩

-

Goobjoog News, Auditor General probes Ministry of Health over donor funds diversion, 2 May 2020, https://goobjoog.com/english/auditor-general-probes-ministry-of-health-over-donor-funds-diversion/. A copy of the letter from the Federal Office of the Auditor General was obtained by the GI-TOC. ↩

-

A copy of the letter from the permanent secretary was obtained by the GI-TOC. ↩

-

Radio Dalsan, Former president accuses government of squandering COVID-19 fund, 25 May 2020, https://www.radiodalsan.com/en/2020/05/25/former-president-accuses-government-of-squandering-covid-19-fund/. ↩

-

Images of the cargo arriving in Adado posted to social media demonstrate that a private company, Maandeeq Air Logistics flight (registration 5Y-SMS), delivered the consignment, whereas most other distribution flights have been carried out by UN agencies. Somalia Covid19, ‘Dowladda FS ayaa qalab caafimaad oo lagula tacaalo #COVID19…’, Twitter post, 2:58 p.m., 28 May 2020, https://twitter.com/SomaliaCovid19/status/1265975805957550081. ↩

-

See Cadaado Covid19, ‘MAHAD-CELIN. Waxaan u mahadcelinynaa Ganacsade…’, Twitter post, 4:49 p.m., 28 May 2020. ↩

-

See, for example, Asad Abdullahi Mataan, Sawirro: Musuq-maasuqii uu Shariif ku eedeeyey DF oo bannaanka usoo baxay, Cassimada Online, 4 June 2020, https://www.caasimada.net/sawirro-musuq-maasuqii-uu-shariif-ku-eedeeyey-df-oo-bannaanka-usoo-baxay/. ↩

-

Using photos posted by the Ministry of Health, the GI-TOC was able to match particular brands of donated face masks to those found in pharmacies. ↩

-

Interview with GI-TOC source on 18 June 2020, by phone. ↩