Criminal plasticity: the growing threat of 3D-printed weapons in South Eastern Europe.

3D printing has revolutionized manufacturing across industries, bringing innovation to medicine, aerospace and consumer products. But there is a darker side to this technological marvel. Criminals and extremists are exploiting 3D printing to create untraceable, fully functional weapons known as ‘ghost guns’. As 3D printers become more affordable and sophisticated, the potential for criminal use grows exponentially. Without strict oversight and regulation, anyone with a printer and an internet connection could produce deadly firearms, greatly complicating efforts to prevent violence and crime. The problem is already significant and growing in a number of South Eastern European and neighbouring countries, particularly Greece and Türkiye, with an alarming potential to spread throughout the Balkan peninsula.

The technology behind 3D-printed weapons

3D printing creates objects by layering materials such as plastic, metal or polymers according to precise digital designs. While this method has gained popularity in various industries for its speed and accuracy, it has also opened a Pandora’s box of security concerns, particularly regarding the illegal production of weapons and other dangerous items.1

A pivotal moment came in 2013, when Defense Distributed, a Texas-based manufacturing and design facility, released digital files for the Liberator, the first almost entirely 3D-printed gun. This breakthrough sent shockwaves through security agencies worldwide, demonstrating that a working firearm could be produced by anyone with basic technological access. Unlike conventional weapons, these 3D-printed guns have no serial numbers, making them virtually untraceable and alarmingly easy to distribute. As technology advances and access becomes more universal, the risk of criminals and extremists covertly printing lethal weapons is rapidly escalating, posing a serious threat to public safety.2

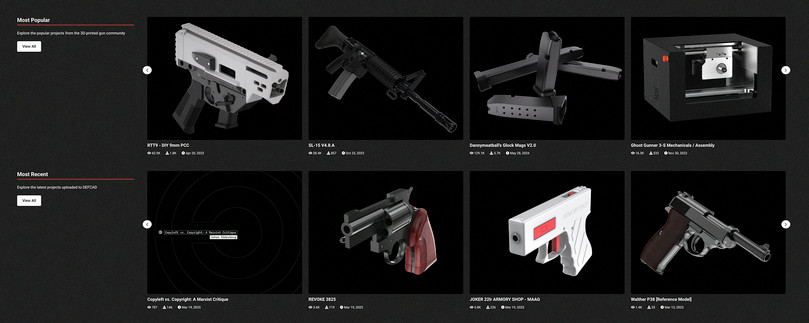

Defense Distributed’s ‘wiki weapon’ repository, DEFCAD.

Photo: Screenshot from DEFCAD

The landscape of 3D-printed firearms has developed swiftly since 2013, with multiple models of varying specifications emerging (see Figure 1). More complex designs have followed the Liberator, such as the AR15 lower receiver, a critical component of a semi-automatic rifle, and the FGC-9, a sophisticated 9mm submachine gun developed in 2020. The capabilities of these weapons showcase the terrifying potential of additive manufacturing technology when applied to the production of firearms, particularly as these weapons are able to effectively bypassing traditional gun control measures.3

| Gun model/part | Designer | Type | No. of 3D-printed parts | Approximate printing time | Material | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberator | Cody Wilson | Pistol | 14 | 20 hours | ABS | 2013 |

| AR15 lower receiver | Cody Wilson | Part of AR-15 semi-automatic rifle | 1 | 9 hours | ABS | 2013 |

| 1911 DMLS 9mm | Solid Concepts | 9mm pistol | 33 | 34 hours | Stainless steel, Inconel 625, PA12 | 2013 |

| Glock body | Deterrence Dispensed | Glock 9mm pistol body | 1 | 11 hours | ABS | 2016 |

| Rapid Additively Manufactured Ballistics Ordnance (RAMBO) | Armament Research, Development and Engineering Center (ARDEC) | 40mm grenade launcher pistol | 30–40 | 48 hours | 4340 steel, aluminium, ABS, PL12 | 2016 |

| FGC-9 | Jacob D/Deterrence Dispensed | 9mm submachine gun | 17 | 90 hours (for all parts) | PLA+ | 2020 |

Figure 1 Types of 3D-printed guns and parts available worldwide.

Source: Samu Rautio and Mika Broms, Security scenarios: 3D printed firearms, Security and Defence Quarterly, 48, 4 (2024).

Law enforcement agencies worldwide are increasingly confronted with this escalating threat, as criminal actors are now able to manufacture fully functional firearms in their own homes, circumventing background checks and avoiding serial number registration. Europol has issued stark warnings, with police forces across Europe reporting increasing seizures of 3D-printed firearms and their use in crimes.4 In 2019, a deadly attack in Halle, Germany, was carried out with a firearm made using 3D-printed components, claiming two lives. In 2021, Spanish police shut down an illegal workshop in the Canary Islands where criminals were making 3D-printed weapons.5 In October 2022, British police raided a suspected gun factory in north-west London and uncovered a large cache of 3D-printed firearms and ammunition in one of the most significant seizures of these weapons in the United Kingdom to date.6 Around the same time, Icelandic authorities arrested four people for plotting to use 3D-printed firearms in attacks on politicians.7

The Balkan powder keg

The Western Balkans are particularly vulnerable to this emerging threat. The legacy of past conflicts has already resulted in the widespread circulation of illegal firearms,8 providing fertile ground for the proliferation of these new untraceable weapons. Although evidence of significant production of 3D-printed weapons in the Western Balkans remains limited, countries in and adjacent to South Eastern Europe, such as Greece and Türkiye, are increasingly confronting the issue.

In Greece, authorities dismantled an illegal operation on the island of Samos in February 2024.9 A group of four young men had established a clandestine manufacturing network, producing and selling 3D-printed semi-automatic weapons to local buyers. When police raided their operation, they discovered a 3D printer actively generating firearm parts, detailed weapon blueprints and a stockpile of components ready for assembly. The group were not only selling guns, but were part of a growing underground network using encrypted online platforms to connect with others looking to make their own weapons. This case revealed a disturbing new reality: with minimal equipment and internet access, even small, isolated groups can turn ordinary spaces into illegal weapons factories.10

Neighbouring Türkiye represents another critical point of vulnerability. A key transit point between the Balkans and the Middle East, Türkiye is already a hotspot for arms trafficking, with an extensive black market supplying both organized crime networks and paramilitary groups. The country has already seen models such as the FGC-9 appear on its black market.11 Since mid-2022, these semi-automatic firearms, which can largely be produced with a 3D printer, have been listed for sale in Istanbul for between 18 000 and 20 000 Turkish liras (€470–€530).12 Some sellers even claim to have modified these weapons for fully automatic fire, although these assertions remain unverified.13 While no major incidents involving 3D-printed firearms have been publicly reported in Türkiye, the growing risk raises concerns about potential spillover into adjacent regions.14

Bulgaria presents another avenue for this looming threat. Although there is no public evidence that these weapons are being produced or widely used in Bulgaria, journalist briefings indicate that some are being manufactured and sold on black markets across the Balkans.15 Despite being subject to the European Union’s Firearms Directive, which regulates all firearms, including those manufactured using 3D-printing technology, the lack of significant police operations specifically targeting 3D-printed weapons raises concerns about potential gaps in monitoring and enforcement.16

Regional and global implications

The ongoing conflict in Ukraine has further complicated the region’s security landscape, fuelling instability and accelerating weapon proliferation. A recent study by the South Eastern and Eastern Europe Clearinghouse for the Control of Small Arms and Light Weapons (SEESAC) warned of an increasing security risk across the region and the European Union, linking these weapons to expanding criminal activity.17 With recent indications that the war may be nearing a resolution, there remains uncertainty about how unresolved issues will affect organized crime, particularly the influx of new types of weapons into Europe.18

Recognizing these complex challenges, the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime hosted a conference in Brussels in January 2025, specifically designed to examine the potential trajectories of the Ukraine conflict and their impact on arms trafficking.19 Experts used scenario modelling to assess how changes in the conflict could shape smuggling patterns and what measures could help mitigate emerging risks. Echoing the recommendations of the SEESAC report, the conference discussion emphasized the need for strengthened regional cooperation and intelligence-sharing, improved monitoring and data collection, and proactive engagement.

The proliferation of 3D-printed weapons is a dynamic and evolving security challenge for South Eastern Europe, with clear warning signs already visible in Greece, Bulgaria and Türkiye. As 3D-printing technology becomes more accessible and refined, the Western Balkans, with its history of conflict and with established illicit arms networks, risks becoming the next frontier for these untraceable weapons.20

While there have not yet been any significant incidents involving 3D-printed weapons in the Western Balkans, the increasing availability of digital blueprints and 3D-printing technology makes it is only a matter of time before the region faces similar challenges to its neighbours. Preventative action now could help prevent a wave of untraceable firearms from entering the black market,21 and contain a threat that has the potential to reshape the security landscape of an already fragile region.

Notes

-

Andrew Philip Hunter, Asya Akca and Emma Bates, Achieving an additive manufacturing breakthrough, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, 22 June 2021; GI-TOC, Tomorrow’s fire: Future trends in arms trafficking from the Ukraine conflict, February 2025. ↩

-

Yannick Veilleux-Lepage, Ctrl, hate, print: Terrorists and the appeal of 3d-printed weapons, International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 13 July 2021. ↩

-

3D-printed weapons are generally considered illegal in European countries, but there are differences in how these laws apply in practice, and the ready availability of digital blueprints makes it difficult for authorities to police. ↩

-

Europol, Printing insecurity: Tackling the threat of 3D printed guns in Europe, 27 May 2022. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Margaret Davis, Haul of 3D-printed gun parts and bullets one of largest in UK, The Independent, 12 October 2022. ↩

-

Daniel Boffey, Icelandic police arrest four people over alleged terror attack plans, The Guardian, 22 September 2022. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Samos: criminal organization made guns with 3D printer, 4 arrests, Tovima.com, 23 February 2024. ↩

-

Ibid ↩

-

3D-printed ‘FGC-9’ firearms emerge on black market in Turkey, Militant Wire, 1 September 2022. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with a journalist in Ankara, Türkiye, 11 December 2024. ↩

-

Interview with a journalist in Sofia, Bulgaria, 14 October 2024. ↩

-

European Commission, Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, 27 October 2021. ↩

-

SEESAC, SEESAC releases comprehensive study on the emerging threat of 3D-printed firearms, 30 October 2024. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

GI-TOC, Tomorrow’s fire: Future trends in arms trafficking from the Ukraine conflict, February 2025. ↩

-

Interview with a police officer in Athens, Greece, 8 December 2024. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩