How informal miners in Mozambique bear the brunt of criminalization while elites seize more control of mining concessions.

Artisanal miners stand above a site where they search for rubies on the outskirts of the mining town of Montepuez, northern Mozambique.

Photo: Emidio Josine/AFP via Getty Images

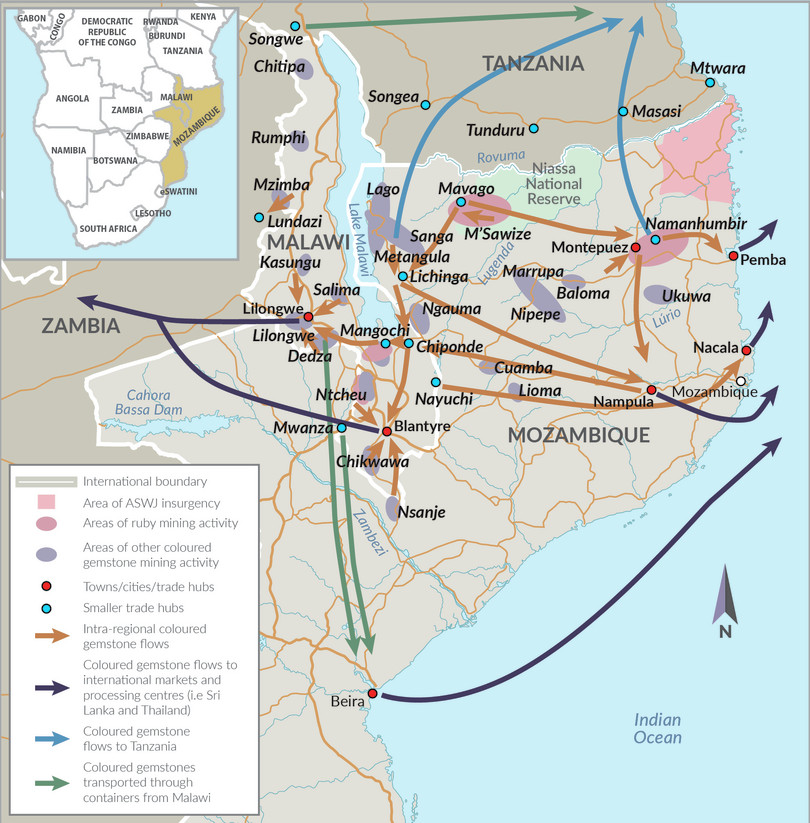

Mozambique is estimated to produce as much as 80% of the world’s ruby supply.1 In northern Mozambique, most ruby mining is concentrated around Namanhumbir, east of Montepuez in the Cabo Delgado province, and to a lesser degree around M’Sawize in the Niassa Special Reserve, a protected wildlife area along Mozambique’s border with Tanzania.

Many of these rubies are extracted by artisanal and small-scale mining operations. However, much of this activity is illegal, either because it is unlicensed – following the Mozambican government’s introduction of compulsory mining licences in 2016 for artisanal miners – or because it takes place in protected areas or private mining concessions owned by large-scale mining companies. 2

Pushing informal mining into the illegal sphere means that these miners – typically referred to as garimpeiros – have to operate clandestinely and often negotiate with corrupt security forces for access to mining areas. Their precarious and criminalized position also puts them at risk of abuse from security forces.

Meanwhile, new investigations into the ownership of mining concessions have found that political elites have been tightening their hold over mining rights in Cabo Delgado, even as a fierce insurgency has raged in northern part of the province.

The experiences of the garimpeiros

In GI-TOC fieldwork in early 2021 in Montepuez, M’Sawize and surrounding mining areas, miners and gem traders described how corrupt police – nominally charged with securing the mine concessions – and the Associação dos Combatentes, a mining association controlled by former independence fighters in Lichinga that holds the licence to mine at M’Sawize3 act as gatekeepers to the informal miners in the respective locations.4 As one middleman put it: ‘There is no law that protects artisanal miners in Mozambique. As such, the police monopolize everything.’5 It was reported that police officers may allow access to mining areas for a small bribe.6 Officers stationed near mine sites will often bribe their superior officers to ensure that they are not redeployed. In other cases, police officers enter into profit-sharing agreements with miners or run mining operations themselves.7

In Montepuez, at the large-scale ruby mining concession controlled by Montepuez Ruby Mining (MRM) – a joint venture between Mozambican company Mwiriti and global gemstone-producing giant Gemfields – miners continue to illegally mine the concession, often bribing police to gain access at night,8 typically for a slot of two to four hours, before the police or security guards signal that it is time to leave. Miners then take excavated soil with them for washing and processing,9 before selling their rubies to Thai, Sri Lankan and West African buyers in Montepuez.10 There are reports that local gemstone buyers fund excavation teams and, in some cases, provide miners with the money to pay the necessary bribes.11

On 10 June 2021, three police officers, three members of MRM security contractor GardaWorld and one MRM employee were found guilty of facilitating illegal mining at the MRM concession by the Montepuez district court.12 Other police officers have also allegedly been funding teams of garimpeiros to mine in the concession.

Figure 10 Northern Mozambique ruby flows.

Some female mine workers report that law enforcement officers have demanded sex in exchange for allowing them to enter the MRM concession. Often these women are Tanzanian who, because of their status as undocumented migrants in Mozambique, frequently do not report cases of sexual assault to the police, fearing that their complaints will not be investigated, or worse, that they will suffer reprisals such as being forced to pay bribes to avoid being arrested because of their illegal residency status. Some female miners form sexual relationships with law enforcement officers to protect themselves from other predatory officers.13

While allegations of misconduct by local law enforcement persist, there are also reports that an increasing number of officers are no longer accepting payments in return for access to the concession. As a result, gaining access to the concession has become more difficult for artisanal miners,14 cutting them off from the livelihood they had previously been (illegally) able to negotiate access to.

There has been tension between police and private security around mining concessions and artisanal miners for many years. Since 2012, there have been allegations of land clearances and violent removals being carried out by police units around the MRM concession.15 After the government changed the regulations governing artisanal mining in 2016, introducing the requirement for artisanal miners to be licensed by forming registered associations, state and private security forces forcibly removed thousands of artisanal miners digging in the ruby fields near Montepuez.16

In Niassa Special Reserve, in addition to the Associação dos Combatentes controlling access to mine sites, miners made similar allegations that police officers are involved in the sector themselves,17 controlling and extorting miners through the threat of violence and facilitating illegal mining through bribes.18 Allegations of punitive measures such as forced expulsions, lengthy imprisonment and extrajudicial beatings to control and reduce illegal mining were also made against police in Niassa Special Reserve following the introduction of compulsory licences.19

In 2019, Gemfields settled a case – including agreeing to pay US$7.6 million compensation – to a group of artisanal ruby miners and residents in the local vicinity of the MRM concession.20 The claimants alleged that the mine’s security forces had committed serious human rights violations, including shootings, beatings, rapes and degrading treatment. The group of claimants included families of artisanal miners who were allegedly killed on the mine, either shot, beaten or buried alive in mine shafts. The company did not admit liability for the violence but did acknowledge that violence had taken place on its mining area.21

As the insurgency in Cabo Delgado has advanced, increasing numbers of displaced people – estimated to be as many as 10 000 – have arrived at the mining concession in Montepuez, fleeing the violence around their homes further north. Desperate for an income source, many have sought illegal mining work on the MRM concession.22 This has resulted in intensified clashes between mine security and artisanal miners.23

Control of mining concessions by the Mozambican political elite

In July 2021, Maputo-based NGO the Public Integrity Centre (CIP) published an analysis finding that attributions of mining concessions have shot up since the start of the Cabo Delgado conflict.24 From 1992 to 2016, the year before the start of the armed conflict in Cabo Delgado, 67 mining concession licenses were attributed in the province. However, from 2017 to February 2021, after the start of the conflict, 46 licenses were attributed in only four years: a rise from an average of five per year to an average of 12. This runs counter to what one would expect: that investors would be unwilling to take on new assets in a region currently gripped by a violent insurgency.

The study went on to investigate the owners of these new concessions using data obtained from the National Mining Institute and other government sources, revealing the extent to which some of the richest resources in Mozambique are concentrated in the hands of a privileged few.

The CIP analysis found that ‘the ownership of a good portion of the concessions is owned by politically exposed people or directly linked to influential individuals from the Frelimo party’. Many owners remained unidentifiable, as many companies involved are registered outside Mozambique, including several based in Mauritius, which is considered a tax haven.

The biggest single holder of concessions in the province is Mwiriti, owned by retired general Raimundo Domingos Pachinuapa and his business partner Asghar Fakhraleali. Mwiriti owns MRM in partnership with Gemfields, and owns 7% of mining concessions in the province (according to CIP analysis).

Pachinuapa, a former independence fighter and the first governor of Cabo Delgado, is a senior figure in the ruling Frelimo party.25 He is a member of the Makonde ethnic group to which President Filipe Nyusi belongs.26 Pachinuapa’s son Raime is MRM’s director of corporate affairs and MRM is chaired by Samora Machel Jr, son of Mozambique’s independence-struggle leader.27

Economic exclusion and radicalization

Resentment among local communities at elite capture of the economic benefits of the natural resources of northern Mozambique – including the ruby fields and the natural gas resources –, which lie beneath the land they farm and which they rely on for their livelihoods, is something that many analysts view as a factor that has fuelled the radicalization across the region and brought fighters to the Islamist insurgency.28

Analysis published in June by the International Crisis Group argued that the violent expulsions from the mine areas deprived ethnic Mwani of an income stream, and that several farmers joined the militants in a reaction against the control of ethnic Makonde over the mining concession in Montepuez.29

João Feijó at the Mozambique-based think tank Observatório do Meio Rural has published information on what is known about the leaders of the insurgency. One key leader, Maulana Ali Cassimo, has reportedly protested against the harsh treatment and detention of artisanal miners working in Niassa Reserve, arguing that mining was one of the few economic options available to these miners.30

MRM has refuted claims that the impact of its project may have fed community feelings of exclusion that have fed into the insurgency, telling The Continent newspaper that its own investigations have found this suggestion to be ‘absurd and misleading’.31

What is the impact of framing informal mining as a criminal issue?

Informal mining is a large part of the local economy in northern Mozambique, a region with exceptionally high levels of poverty and few legitimate economic opportunities. As people have been displaced from the northern area of Cabo Delgado, the clashes between security forces and informal miners have intensified.

While these clashes with informal miners are framed as an issue of criminality, mining in northern Mozambique is much more complex. It is an issue of justice and land rights over the richest resources available in a deeply impoverished region. It is also an economic issue, because mining – even while risky and criminalized – is one of the few livelihood opportunities available in the region. Finally, it is a health and environmental issue due to the impact of mining activities on the health of local populations and ecosystems.

There is a stark contrast between the experiences of the garimpeiros, negotiating a corrupt system that can turn brutal, and the Mozambican political elite tightening control of natural resources amid a violent insurgency.

This article draws on research from the upcoming GI-TOC report ‘Scratching the Surface: Tracing coloured gemstone flows from northern Mozambique and Malawi to Tanzania, Thailand and Sri Lanka’ by Marcena Hunter, Chikomeni Manda and Gabriel Moberg.

Notes

-

Jason Boswell, Mozambique’s lucrative ruby mines, BBC, 10 February 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/av/business-38934307. ↩

-

In 2003, artisanal mining licences and permits were created for Mozambican citizens. More recently, there has been a push to get artisanal miners to register as associations. In 2016, this policy became law, rendering what was previously merely ‘informal’ mining illegal. Built into this initiative have been efforts to exclude non-Mozambican nationals from artisanal and small-scale mining, with artisanal mining associations required to consist solely of local stakeholders. However, compliance with the new rules has been limited due to lack of state capacity, corruption, high levels of bureaucracy and artisanal mining zones lacking sufficient deposits. As a result, much of the coloured gemstone artisanal and small-scale mining in northern Mozambique today is illegal. ↩

-

Interviews with Mozambican and Tanzanian dealers, Mavago and Lichinga, January 2021. ↩

-

The study followed a mixed-methodology approach, taking advantage of primary research carried out by field investigators, complemented by a literature review. Remote interviews were also conducted by telephone. Researchers visited trading centres, including Lichinga, Mavago, M’Sawize, Montepuez, Namanhumbir and Nampula in Mozambique in January 2021, and Lilongwe and Mangochi in Malawi in February 2021. Interviews were carried out with government officials, police officers, civil society actors, industry experts, private sector actors and security officials, gemstone dealers, brokers and miners. ↩

-

Interview with gemstone middleman, January 2021. ↩

-

Interview with NSR conservationist, Niassa, January 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with miners and dealers, Mavago, January 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with Tanzanian buyers, brokers and miners, Montepuez, January 2021. ↩

-

Interview with Tanzanian miner and dealer, Montepuez, January 2021. ↩

-

Roundtable interview with industry experts, June 2021, by teleconference. ↩

-

Interview with Tanzanian female miner and dealer, Montepuez, January 2021. ↩

-

Mozambique: six sentenced for facilitating illegal ruby mining, Club of Mozambique, 10 June 2021, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/mozambique-six-sentenced-for-facilitating-illegal-ruby-mining-194205/. ↩

-

Interview with Tanzanian female miner and dealer, Montepuez, January 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

The business interests of General Raimundo Pachinuapa, Centro de Jornalismo Investigativo, 13 April 2020; Estacio Valoi, The blood rubies of Montepuez, Foreign Policy, 3 May 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/05/03/the-blood-rubies-of-montepuez-mozambique-gemfields-illegal-mining/. ↩

-

David Matsinhe, Mozambique: the forgotten people of Cabo Delgado, Daily Maverick, 29 May 2020, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-05-29-mozambique-the-forgotten-people-of-cabo-delgado/. ↩

-

Note that only the Association of Former Combatants of Lichinga has the right to mine in Niassa Special Reserve, and that other local communities and foreign miners operate in the reserve illegally. ↩

-

Marcena Hunter, Pulling at golden threads, ENACT, April 2019. ↩

-

See for example Gemmological Institute of America, Conservation, rubies and gold mining in Mozambique [video], YouTube, 2018, https://youtu.be/TBXdnma7QBQ. ↩

-

Cecilia Jamasmie, Gemfields to pay $7.8m to settle human rights abuses claims in Mozambique, mining.com, 29 January 2019, https://www.mining.com/gemfields-pay-7-8m-settle-claim-human-rights-abuses-mozambique/. ↩

-

Leigh Day statement on the Gemfields case, 2019, https://www.leighday.co.uk/latest-updates/cases-and-testimonials/cases/gemfields/. ↩

-

Roundtable interview with industry experts, June 2021, by teleconference. ↩

-

Joseph Hanlon, Special report: Evolution of the Cabo Delgado war, Club of Mozambique, 27 February 2020, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/special-report-evolution-of-the-cabo-delgado-war-by-joseph-hanlon-153785/. ↩

-

Public Integrity Centre (CIP), Requests for mining concessions increase as armed conflict in Cabo Delgado intensifies – Who are the owners of mining licences in Cabo Delgado?, 20 July 2021, https://www.cipmoz.org/en/2021/07/20/8153/. ↩

-

Luis Nhachote, Cabo Delgado is a warzone, but profiteers strike it rich, Mail & Guardian, 4 September 2021, https://mg.co.za/africa/2021-09-04-cabo-delgado-is-a-warzone-but-profiteers-strike-it-rich/. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Estacio Valoi, The deadly rubies of Montepuez, Oxpeckers, 15 March 2016, https://oxpeckers.org/2016/03/the-deadly-rubies-of-montepuez/. ↩

-

Joseph Hanlon, Special report: Evolution of the Cabo Delgado war, Club of Mozambique, 27 February 2020, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/special-report-evolution-of-the-cabo-delgado-war-by-joseph-hanlon-153785/; Joseph Hanlon, Mozambique’s jihadists and the ‘curse’ of gas and rubies, BBC, 18 September 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-54183948. ↩

-

International Crisis Group, Stemming the Insurrection in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado, 11 June 2021, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/southern-africa/mozambique/303-stemming-insurrection-mozambiques-cabo-delgado. ↩

-

João Feijó, From The “Faceless Enemy” To The Hypothesis Of Dialogue: Identities, Pretensions And Channels Of Communication With The Machababs, OMR, 10 August 2021, https://omrmz.org/omrweb/wp-content/uploads/DR-130-Cabo-Delgado-Pt-e-Eng.pdf. ↩

-

Luis Nhachote, Cabo Delgado is a warzone, but profiteers strike it rich, Mail & Guardian, 4 September 2021, https://mg.co.za/africa/2021-09-04-cabo-delgado-is-a-warzone-but-profiteers-strike-it-rich/. ↩