The targeting of three women in South Africa shows how violence is shaping politics in the run-up to local elections.

Ward Councillor Nokuthula Bolitye, here pictured on the right during a community meeting in Cape Town, was assassinated in July 2021.

Photo: GCIS/South African government/Flickr

Babita Deokaran, acting chief financial officer at the Gauteng Department of Health, was a crucial witness in a corruption investigation, headed by South Africa’s Special Investigating Unit,1 into irregularities in a R332 million personal protective equipment deal at the department.2 Deokaran’s testimony would have allegedly implicated top-level officials.3

Deokaran was attacked outside her home on 23 August 2021. Hitmen opened fire as she returned home after dropping her child at school. She was transferred to hospital but died from her wounds.4 The hitmen had allegedly been monitoring her for over a month and had meticulously planned the operation, ensuring the nearby CCTV cameras were turned off at just the right time.5 However, thanks to evidence from a neighbour regarding the registration of the hitmen’s car, the police were able to arrest the hitmen within a few days.6 Investigations are ongoing, but the identity of those who ordered the hit have yet to be confirmed.

Just two days before, Ntobe Shezi, an African National Congress (ANC) candidate for ward councillor in Mid Ilovo in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands, survived an assassination attempt. Hitmen opened fire while she was returning home after a voting meeting.7 Six weeks earlier, on 12 July, Ward Councillor Nokuthula Bolitye was also gunned down outside her home.8 Bolitye was a ward councillor in Crossroads, a notoriously dangerous area of Cape Town. Like most other hits, there have been no reported arrests in either of these cases, but the modus operandi of attacking a victim outside their home is a common feature of assassinations carried out by organized crime groups. Our monitoring has found that there have been six other political hits in South Africa in the past two months.

Political assassinations in context

Political hits, like those on Deokaran, Shezi and Bolitye, have been a consistent feature of South African politics for at least two decades. The GI-TOC has been monitoring assassinations in South Africa since 2000 and has built a database to analyze the nature and extent of targeted killings. Between 2000 and 2020, our database recorded a total of 1 822 assassinations, of which 404 (22%) were political hits. Overall, recent years have been more violent, with the last six years of the 21-year data set accounted for 47% of the total number of assassinations.9 As can be seen in Figure 7, the number of cases steadily increased from 2015, peaking in 2018, followed by a decline in 2019 and 2020.

Figure 7 Assassination cases in South Africa recorded by the GI-TOC, 2000–2020, by category.

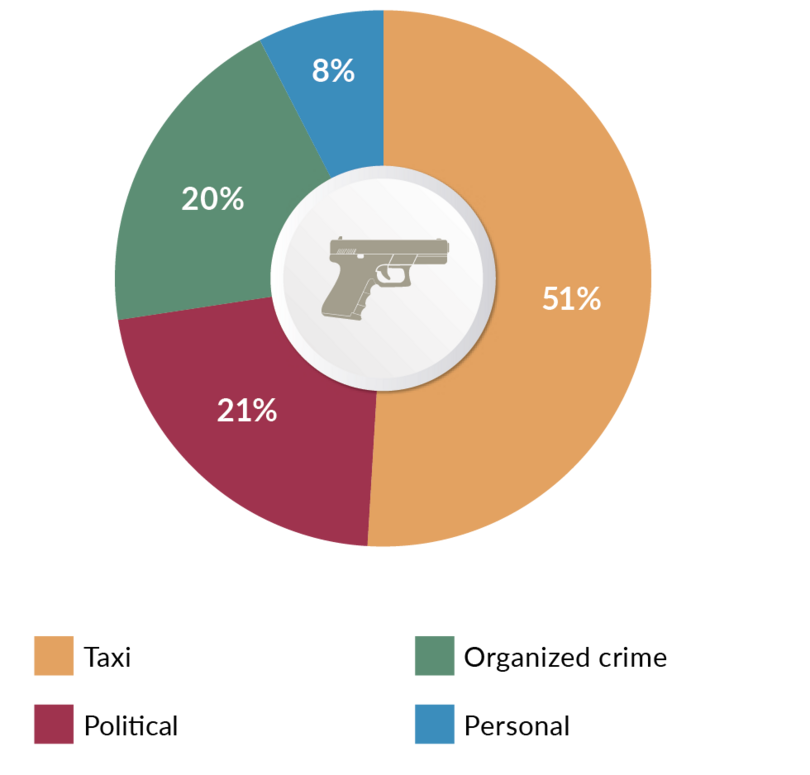

The number of hits classified as political, organized-crime related and personal have remained fairly stable through the 21-year period. Cases related to political motives and organized crime show a slight but steady increase over time (barring a decline in 2020), while cases related to personal gain remain consistently low. The major volatility in rates of assassinations over time have been caused by notable peaks and troughs in hits in the taxi industry. This was likely due to increases specifically in Gauteng and the Western Cape. This sector is the largest single source of assassinations in South Africa: for the period 2015–2020, taxi hits accounted for 51% to the total number of assassinations in South Africa (Figure 8). Hits associated with political motives and organized crime accounted for 21% and 20% of hits respectively, while 8% of hits were for personal gain.

Figure 8 Assassinations by category, 2015–2020.

Characteristics of political assassinations

The assassination of whistle-blowers (like Deokaran) and local government officials (such as Bolitye) are two of the most common types of politically motivated assassinations in our database.

The targeted killing of ward councillors, or candidates for councillors, leading up to local government elections is not new. Our database shows that in the lead-up to elections the increase in competition for ward council nominations often ends in violence as candidates ‘take out the competition’.10

The position of ward councillor provides not only status and connections within the community but also comes with a significant financial benefit: ward councillors for the municipality of eThekwini, KwaZulu-Natal, for example, are estimated to earn around R400 000 per year,11 almost 10 times the national minimum wage (around R45 000 per year).12 This financial incentive may in part drive the trend for eliminating the competition. Although councillors are barred from serving on any tender committees, they allegedly often have influence over the outcome through their connections. Being elected as a councillor is also considered one of the key first steps in climbing the political ladder.

Between 2015 and 2020, political assassinations were concentrated in KwaZulu-Natal (Figure 9), which matches trends shown by earlier data.13 The province accounted for 56% (103 deaths) of the total number of political hits in this period.14 This was followed by 22 cases (12%) in Gauteng, 20 cases (11%) in the Eastern Cape and 15 cases (8%) in the Western Cape.

Assassinations in KwaZulu-Natal peaked in 2016 and 2019. Both years were election years: 2016 saw municipal elections in August and national elections were held in 2019. The attempted assassination of Ntobe Shezi continues this trend of pre-election targeting of candidates.

In 2020, there was a drastic decrease in political hits in KwaZulu-Natal. This was probably due, at least in part, to the national COVID-19 lockdown, which meant that political branch meetings and conferences, which can be flashpoints for violence, did not take place. But the extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic means that the 2020 decline in political hits in KwaZulu-Natal is likely to be a temporary pause in violence rather than the start of a long-term trend.

The province has a long-standing history of political violence, both during apartheid and in the transition to democracy.15 Previously, violence was largely related to interparty conflict between the ANC and the Inkatha Freedom Party, and mostly linked to political ideology.16 However, the trend now seems to be that violence results from intraparty conflict particularly within the ANC; with targeted killings fuelled by power struggles and competition for lucrative government tenders.17

Figure 9 Assassinations by province, 2015–2020.

A candlelit vigil is held in memory of whistle-blower Babita Deokaran on August 2021 in Johannesburg, South Africa, after she was shot and killed in what investigators believed was a targeted hit.

Photo: Fani Mahuntsi/Gallo Images via Getty Images

The magnitude of political violence in the province resulted in an official government-appointed inquiry being established in 2016, headed by Advocate Marumo Moerane. The Moerane Commission’s report, released in 2018 and based on the testimony of 63 witnesses, including police, activists, academics and violence monitors,18 found that that ‘there was overwhelming evidence from the majority of witnesses that access to resources through the tender system is the main root cause of the murder of politicians’.19

The commission further found that ‘criminal elements are recruited by politicians to achieve political ends, resulting in a complex matrix of criminal and political associations that also lead to the murder of politicians’.20 Councillors have also allegedly been killed after publicly criticizing corruption.21 The report made valuable findings and it is hoped that the recommendations – if implemented – will lead to a long-term decrease in political violence in the province.

KwaZulu-Natal was also the epicentre of the violence that flared up following the imprisonment of former president Jacob Zuma. It was the worst episode of civil unrest since apartheid,22 coming after months of increased political tensions and violence during the first half of 2021. The unrest in the province, and to a lesser extent Gauteng, included widespread protests, looting, burning of buildings and violence, resulting in over 300 deaths.23 In this trying and volatile environment, some industries and corrupt officials have resorted to violence for political or financial gain.

The assassinations of Bolitye and Deokaran and the attempted assassination of Shezi have seen the number of recorded political hits rise to 15 in 2021 so far. With the current political tensions in South Africa and violent competition leading up to the local government elections due to be held on 1 November 2021, more councillors and candidates may fall victim to political hits. Likewise, the increase in whistle-blowing and corruption investigations could mean that more witnesses and whistle-blowers will meet the same fate as Deokaran before the year is over, especially given the lack of protection afforded to witnesses in such cases.24

This article draws on research from the GI-TOC’s recent report ‘Murder by contract: Targeted killings in eastern and southern Africa’. The report analyzes targeted killings in Kenya, Mozambique and South Africa for the period 2015–2020. It explores the impact of these killings on the respective countries’ society, economy and democracy, identifying causes and possible solutions to the phenomenon.

Notes

-

The Special Investigating Unit provides forensic investigation and civil litigation services to combat corruption, serious malpractices and maladministration to protect the interests of the State and the public in South Africa. For more see: https://www.siu.org.za/. ↩

-

Vincent Cruywagen, Police closing in on killers of corruption whistle-blower Babita Deokaran – sources, Daily Maverick, 25 August 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-08-25-police-closing-in-on-killers-of-corruption-whistle-blower-babita-deokaran-sources/. ↩

-

Vincent Cruywagen, Slain whistle-blower Babita Deokaran potentially unveiled a criminal syndicate at the Department of Health, Daily Maverick, 28 August 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-08-28-slain-whistle-blower-babita-deokaran-potentially-unveiled-a-criminal-syndicate-at-the-department-of-health/?utm_source=homepagify. ↩

-

Vincent Cruywagen, Slain whistle-blower Babita Deokaran potentially unveiled a criminal syndicate at the Department of Health, Daily Maverick, 28 August 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-08-28-slain-whistle-blower-babita-deokaran-potentially-unveiled-a-criminal-syndicate-at-the-department-of-health/?utm_source=homepagify. ↩

-

Vincent Cruywagen, Police closing in on killers of corruption whistle-blower Babita Deokaran – sources, Daily Maverick, 25 August 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-08-25-police-closing-in-on-killers-of-corruption-whistle-blower-babita-deokaran-sources/. ↩

-

Suthentira Govender, Corruption buster Babita Deokaran’s suspected ‘killers’ to appear in court, TimesLive, 30 August 2021, https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2021-08-30-corruption-buster-babita-deokarans-suspected-killers-to-appear-in-court/. ↩

-

Fanele Mhlongo, Two ANC councillors living in fear after being attacked in KZN, SABC News, 20 August 2021, https://www.sabcnews.com/sabcnews/two-anc-councillors-living-in-fear-after-being-attacked-in-kzn/. ↩

-

Unathi Obose, Murder investigated, News24, 15 July 2021, https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/local/city-vision/murder-investigated-20210714. ↩

-

There were 858 assassinations between 2015 and 2020. See: Kim Thomas, The rule of the gun: Hits and assassination in South Africa, 2000–2017, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, March 2018, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/The-rule-of-the-gun_AssassinationWitness.pdf. ↩

-

Mark Shaw, Hitmen for hire: Exposing South Africa’s underworld. Johannesburg and Cape Town: Jonathan Ball, 2017; and Kim Thomas, The rule of the gun: Hits and assassination in South Africa, 2000–2017, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, March 2018, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/The-rule-of-the-gun_AssassinationWitness.pdf. ↩

-

See the councillor salaries budgeted for in the eThwekwini municipality 2021–2022 budget, available at: http://www.durban.gov.za/Resource_Centre/reports/Documents/EthekwiniMunicipality2021_22MediumTermBudget.pdf. The city has 200 councillors, meaning the R80 million budget equates to a R400 000 salary average per councillor. ↩

-

Department of Labour, Employment and Labour Minister TW Nxesi announces minimum wage increases, 9 February 2021, http://www.labour.gov.za/employment-and-labour-minister-tw-nxesi-announces-minimum-wage-increases?platform=hootsuite. ↩

-

Kim Thomas, The rule of the gun: Hits and assassination in South Africa, 2000–2017, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, March 2018, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Therule-of-the-gun_Assassination-Witness.pdf. ↩

-

For consistency across the data set, the data is drawn from media reports of assassinations across the country and time period. Yet data collected by our research team in the province suggest that the media picks up only a portion of the cases (about 60–70%), and our database therefore does not reflect the full magnitude of political killings in the province. However, the general trends are in line with the data collected on the ground and therefore can be regarded as a useful barometer of the situation. ↩

-

Rupert Taylor, Justice denied: political violence in KwaZulu-Natal after 1994, African Affairs, 2002, 101, 405, 473; Jo Beall, Sibongiseni Mkhize and Shahid Vawda, Traditional authority, institutional multiplicity and political transition in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 2004, Development Research Centre, Working Paper No. 48, 2; Mario Kramer, Violence, autochthony, and identity politics in KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa): A processual perspective on local political dynamics, African Studies Review, 2019, 1; Report of the Moerane Commission of Inquiry into the underlying causes of the murder of politicians in KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, 2018, 417. ↩

-

Richard Carver, KwaZulu-Natal – Continued violence and displacement, 1996, WRITENET, https://www.refworld.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain?page=publisher&docid=3ae6a6bc4&skip=0&publisher=WRITENET&querysi=kwa-zulu%20natal%20continued%20violence&searchin=fulltext&sort=date; SR Maninger, The conflict between ANC and IFP supporters and its impact on development in KwaZulu-Natal, 1994, (unpublished), University of Johannesburg, 5; Maria Schuld, Voting and violence in KwaZulu-Natal’s no-go areas: Coercive mobilisation and territorial control in post-conflict elections, African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 2013, 13, 1. ↩

-

Report of the Moerane Commission of Inquiry into the underlying causes of the murder of politicians in KwaZuluNatal, Durban, 2018, 413. ↩

-

Greg Arde, War party: How the ANC’s Political Killings are Breaking South Africa, Tafelberg, 2020; Report of the Moerane Commission of Inquiry into the underlying causes of the murder of politicians in KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, 2018. ↩

-

Ibid., 418. ↩

-

Ibid., 415. ↩

-

Ibid., 66. ↩

-

Andrew Harding, South Africa riots: The inside story of Durban’s week of anarchy, BBC, 29 July 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-57996373. ↩

-

Loyiso Sidimba, Unrest death toll in KZN revised down by government, IOL, 23 July 2021, https://www.iol.co.za/news/politics/unrest-death-toll-in-kzn-revised-down-by-government-68557f9a-7b31-4d2c-aafc-e229da8d7a2d. ↩

-

Mark Heywood, Babita Deokaran: How not to get away with murder, Daily Maverick, 31 August 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-08-31-babita-deokaran-how-not-to-get-away-with-murder/. ↩