The new administration in the Seychelles fought the election on corruption issues. Are they addressing drug-related corruption?

In October 2020, a landmark presidential election took place in the Seychelles. Opposition candidate Wavel Ramkalawan unseated the incumbent, Danny Faure, in what was described as a ‘political earthquake’: the first victory for an opposition party in a presidential election since the Seychelles’ independence from the UK over four decades ago.1

Tackling corruption and illicit drugs markets were major themes in the election campaign. The Seychelles is home to a booming illegal drugs market, principally for heroin. The small island nation reports the highest rate of per capita heroin consumption in the world,2 and there is a common public perception that corruption is widespread, which underpins the flourishing drugs market.

Several months into the new administration’s term, questions remain as to whether they are taking action on corruption, and whether the new approach to addressing the drugs market is effective or rather doing harm to PWUD.

People queue to receive methadone at a mobile clinic in the Seychelles, November 2019.

Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP via Getty Images

PWUD participating in the Seychelles methadone programme receive medication on Mahe island, Seychelles, November 2019.

Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP via Getty Images

Corruption has moved up the political agenda

Countering corruption has long been a prominent issue in newly elected president Ramkalawan’s political campaigning. As opposition leader, he pledged to eliminate corruption, nepotism and drug trafficking3 and accused the former president, James Michel, of inaction against known drug traffickers.4 Following the opposition’s majority win in parliament in 2016, the Finance and Public Accounts Committee (FPAC), led by Ramkalawan, revealed several anomalies in public spending, which helped put corruption on the political agenda.5

The FPAC revealed irregular payments amounting to 90 million rupees (US$6.2 million) that involved the Financial Intelligence Unit and the National Drugs Enforcement Agency, now called the Anti-Narcotics Bureau (ANB). The payments were made to two offshore companies based in Mauritius.6 The Irish nationals managing these agencies at the time left the Seychelles among accusations of misconduct prior to these revelations.7

The 2020 election manifesto of Ramkalawan’s party, LDS (the Linyon Demokratik Seselwa or Seychelles Democratic Alliance), argued ‘it is clear that corruption has undermined government and society in our country. It has betrayed good governance principles, the rule of law and justice, and fairness in access to opportunity.’ The party consequently pledged to investigate cases of corruption and implement new policies for combatting drug trafficking.8

These campaigns are thought to have resonated with the Seychelles electorate. ‘The new government campaigned on eradicating corruption in the last election. They probably won because of these promises,’ said Andy Labonte, a member of the now-ruling LDS party in the National Assembly.9

Clive Camille, a journalist with the Seychelles broadcast network, TéléSesel, agreed: ‘[Since] the revelations by FPAC in parliament, corruption has been the talk in the country. Many people are angry about these allegations and want to see justice done.’10 Corruption and drugs markets have become high-priority policy issues in discussions on social media platforms among Seychelles’ voters. In 2017, a survey by the Seychelles Anti-Corruption Commission found that 82.8% of the 15 000 participants considered corruption to be very high in the Seychelles.11

Luciana Sophola, chairperson of the Seychelles civil society organization Association for Rights Information and Democracy, argued that investigations into corruption – relating not only to drugs but also to public-sector corruption as a whole – were often met with resistance. ‘Before, with the old government, there were lots of laissez faire [approaches to corruption issues]. I am not blaming the president, but human beings who could not care less’. She added that, in her experience, there had been many cases when people had reported corruption where the investigation would reach a certain level of seniority before being blocked with no action taken.12

The roots of this corruption can be traced back decades. Former president France Albert René, who came to power in a 1977 coup, reportedly ruled through systems of patronage and cronyism. René was accused of illegally confiscating land and property to put it into the hands of powerful families connected to his party, and of jailing and assassinating political rivals at home and in exile.13

René’s strategies for maintaining power included illegal land grabbing from political opponents and misusing public money for political campaigns. The legacy of this era continues to shape political life in the Seychelles. Commenting on the recent election, Seychelles journalist Patrick Muirhead argued that the incumbent president ‘was unable to distance his party’s campaign from mounting evidence of past political murders, torture and corruption when Seychelles was still a one-party state’.14 Restricted media freedom in the Seychelles has, however, rendered it difficult for corruption to be widely discussed publicly and for journalists to investigate allegations of corruption.15

‘Corruption is part of this national history, ingrained in the culture,’ said Labonte. ‘It will take some time to make people realize that this is not good practice and should stop.’ Now that he is in office, Ramkalawan has reiterated pledges that his government will take firm action on drug trafficking and corruption.16

The Seychelles’ drugs markets are a significant driver of corruption

Heroin is the most significant illegal market in the Seychelles.17 The number of heroin users has grown rapidly in recent years, with the Agency for the Prevention of Drug Abuse and Rehabilitation (APDAR) having estimated the number of users at 5 000–6 000 by November 2019, equivalent to around 10% of the island’s working-age population.18 Other drugs, such as crack cocaine, are now also becoming more commonly used.19

PWUD interviewed by the GI-TOC in 2020 made repeated allegations that corruption is widespread among law enforcement structures. Some reported incidents of drug dealers being arrested but then released after a payoff was made;20 others reported instances of seized drugs being resold by police officers.21 According to interviewees from the Seychelles prison authority, street-level corruption among law enforcement officers has become increasingly brazen and ‘normalized’, with police officers having been witnessed taking bribes openly in front of colleagues and the public.22 Several interviewees – including former ANB officers and representatives of the prison service – specifically identified the ANB as being affected by corruption issues, and the problem extending to a high level.23

Several months after the election, PWUD in the Seychelles report that these trends continue. ‘Drug dealers are highly protected by government officials and police, as well as the drugs community. We know them,’ said John. ‘If the law enforcement and government official say they don’t know who the big dealers are, they are telling you lies because those people are in their circle.’24

‘Brother, dealers are well protected by the police. Even if you know them, you cannot say anything,’ agreed Thomas, another PWUD. Many PWUD echoed these statements, noting that certain traffickers benefit from police protection while investigations are targeted at their rivals.25

Representatives of the Drug Utilization Response Network Seychelles (DURNS), a civil society organization run by current and former PWUD, support these claims.26 DURNS representatives asked: ‘Are you telling me the government cannot trace or do not know these people [major drug traffickers]? The small country that we are? No way.’27

Raymond St. Ange, Superintendent of Prisons, acknowledged that corruption is also an issue among prison staff and that entrenched corruption may take a long time to change. ‘Some people do not want to let go of the benefits of their corrupted activities,’ he said. Given the cost of living in the Seychelles, he argued that the incentive to make money from corrupt activities is high and noted that ‘[many staff] are used to selling cigarettes [and] lighters and smuggling drugs inside the prison’. ‘This is also the case for other government officials,’ he noted. ‘Many law enforcement officers let themselves get trapped in these activities.’28

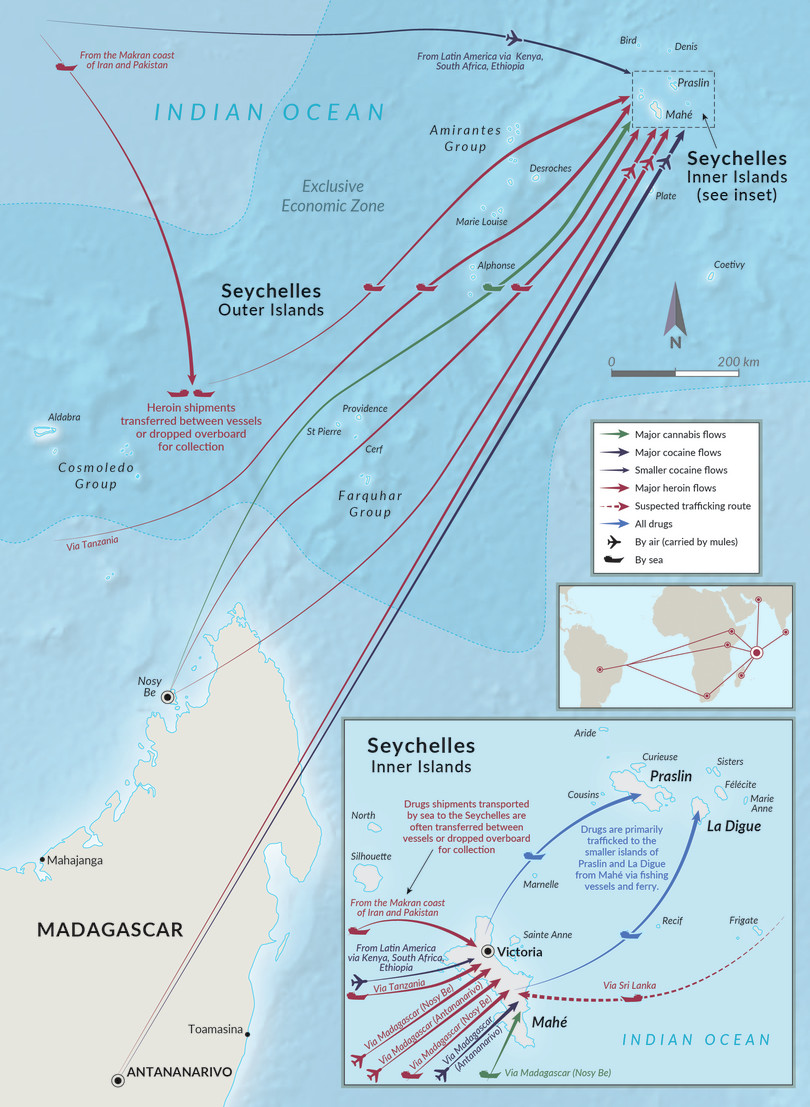

Figure 4 Drug flows in the Seychelles, 2020.

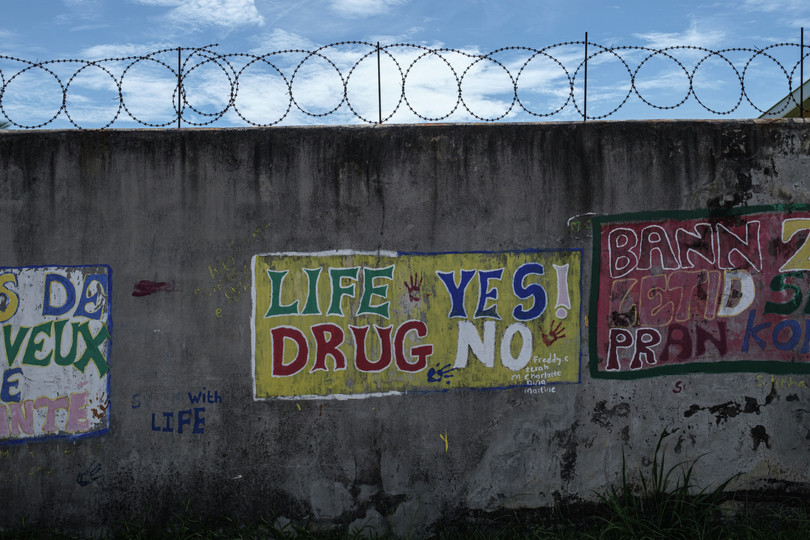

An anti-drug message daubs a wall in Mahe island, the largest in the Seychelles. A sharp rise in heroin use in the past decade means that, today the Seychelles has some of the highest rates of heroin use in the world, equivalent to nearly 10% of the national workforce.

Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP via Getty Images

The Seychelles’ response to reported corruption

Reports of drug-related corruption and rising public frustration about corruption in government have not yet translated into criminal investigations and prosecutions. The Anti-Corruption Commission of the Seychelles reported to the GI-TOC that, as of March 2021, no cases of corruption have yet been criminally prosecuted or passed to the attorney general for criminal investigation.29 The commission was created following new anti-corruption legislation that was passed in 2016. However, they report that to date no cases active under their mandate have picked up corruption allegations relating to drugs issues.30

According to Clive Camille of TéléSesel, the lack of prosecutions does not reflect well on the new administration’s claims to be acting on corruption. ‘As a journalist I see this as a political tactic used by the political party in power to get more credibility and discredit the previous administration,’ he said. ‘We are just hearing “corruption, corruption”, and yet no one has been prosecuted and sentenced.’31

But other commentators, including Sophola, pointed out that the new administration is in its infancy. ‘Most people [expect action on corruption] to happen overnight. It is to be remembered that it has been only five months since the change in government,’ she noted. Sophola argued that the new administration has been taking steps in the fight against corruption that would not have been politically possible before. For example, the president has encouraged greater freedom of information and transparency with the media by ministers, which is hoped to bring about a culture change in government.32

The Eastern and Southern Africa Anti-Money Laundering Group report published in 2018 identified a number of deficiencies in the Seychelles’ financial sector, which led to the country being included on the EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions in 2020.33 Although the country remains on the list following an update in February 2021,34 the new administration has passed amendments to several pieces of legislation to address these deficiencies. The amendments include legislation to promote transparency about beneficial ownership of companies and to facilitate information sharing between enforcement agencies investigating corruption and money laundering.35 These changes have been welcomed by Transparency International Seychelles, which stated that such legislation has ‘a defining role in strengthening efforts to prevent, curb and penalise corrupt activities’.36

PWUD report more police harassment

Although it may be too early to fully assess the new administration’s action on corruption, one change was consistently reported since the new administration took office. PWUD and DURNS representatives report that police patrols at street level have increased and police behaviour towards PWUD has become more aggressive.

‘Now you see them [police] three to four times a day in the ghetto [area where drugs are used]’, said Thomas. ‘They come to harass us, taking away our syringes, which have just been given to us by APDAR, legally. They are more aggressive and abusive in their approach’ he said.37

Jane, another PWUD, agreed. She noted that ANB officers have become particularly aggressive towards the drug-using community. According to her, the situation has become ‘worse than before’, with officers confiscating and throwing away syringes used for injecting heroin, and using tear gas on PWUD.38

These reports suggest that the new administration’s tough stance on corruption and trafficking has driven a parallel law enforcement crackdown on PWUD. This follows claims in the LDS manifesto to ‘eliminate’ drug use in the country.39 PWUD feel that they are being used for ‘political mileage’ by the new administration, in pursuit of policies that will increase the harm of drug use.40

DURNS representatives said that PWUD they work with ‘have expressed concern about the new way of doing things by the police: harassment and abusive behaviour. There is the fear that the policy would regress to zero tolerance like before.’41 ‘Like before’ refers to the period before 2016, when reforms were made to the Misuse of Drugs Act, and the subsequent establishment of APDAR. With these reforms, the Seychelles shifted towards a drug-use policy focused more on ‘harm reduction’ and established initiatives such as an extensive methadone programme. Before this shift, however, a ‘zero tolerance’ approach criminalized drug use. Jane concluded: ‘Drug users are political tools, like pieces on a chessboard.’42

It remains to be seen whether investigations and prosecutions into drug-related corruption will gain any traction under the new administration. In contrast, aggressive actions targeted at PWUD, such as confiscating syringes, undermine harm-reduction work by agencies such as APDAR, and do not address the links between drug trafficking and corruption.

Notes

-

Seychelles election: Wavel Ramkalawan in landmark win, BBC News, 25 October 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-54681360. ↩

-

Figures for 2019 reported by APDAR and cited by the BBC: Kanika Saigal, Why Seychelles has the world’s worst heroin problem, BBC, 21 November 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-50488877; Addiction in paradise: Seychelles battles heroin crisis, France 24, 20 February 2020, https://www.france24.com/en/20200220-addiction-in-paradise-seychelles-battles-heroin-crisis. ↩

-

Response to the State of the Nation Address on 16 February 2017. Salifa Magnan, Sharon Ernesta and Betymie Bonnelame, Seychelles’ National Assembly leaders reply to State of the Nation address, Seychelles News Agency, 16 Fabruary, 2017, http://www.seychellesnewsagency.com/articles/6780/Seychelles+National+Assembly+leaders+reply+to+State+of+the+Nation+address. ↩

-

In a televised debate in 2018 with former president James Michel, Ramkalawan stated: ‘President Michel said he knows who the Escobar/drug dealers are, but why don’t the police arrest them? Is he involved, or are some government officials or some of his friends involved? This cannot go on.’ Broadcast on the Seychelles Broadcasting Corporation programme Tet a Tet, 22 January 2018, available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7fxiIzZfY8. ↩

-

National Assembly, Finance and Public Account Committee Report, 2017, available at: https://www.nationalassembly.sc/publications/reports/fpac-report-report-auditor-general-2015. ↩

-

REGXSA, Seychelles, 5.6 million euros of misappropriated public funds, 23 August 2017, https://www.regxsa.com/ml-tf-updates/seychelles-5-6-million-euros-of-misappropriated-public-funds/. See also: Today in Seychelles, Inquiry into FIU/NDEA payments, 7 September 2017, available at: https://web.facebook.com/todayinsey/posts/thursday-7-september-2017inquiry-into-fiundea-paymentsfpac-to-summon-james-miche/1435217789849360/?_rdc=1&_rdr. ↩

-

Seychelles Weekly, Irish police to depart: Another of President Michel’s schemes falls through, 17 September 2010, http://www.seychellesweekly.com/September%2026,%202010/top5_irish_police_to.html. ↩

-

LDS 2020 General Elections Manifesto, p. 8 and p. 17, available at: https://lds.sc/images/2020/PDF/Manifesto–LDS-25th–September-2020–Web-version.pdf. ↩

-

Andy Labonte, interview, Mahé, Seychelles, 23 March 2021. ↩

-

Clive Camille, telephonic interview, 18 March 2021. ↩

-

Anti-Corruption Commission Seychelles, Public Opinion Survey on Corruption in Seychelles, 2017. Available at: https://www.accsey.com/filing/prevention/Seychelles%20First%20Public%20Opinion%20Survey.pdf. ↩

-

Luciana Sophola, interview, Victoria, Seychelles,12 March 2021. ↩

-

Daniel Kunzler, The ‘socialist revolution in the Seychelles: continuities and discontinuities in economic and social policies; SozialPolitik.Ch, 1, ARTICLE 1.7, http://doc.rero.ch/record/322665/files/2018_1_Kuenzler.pdf. See also Matthew Shaer, Michael Hudson and Margot Williams, Sun and shadows: How an island paradise became a haven for dirty money, International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, 3 June 2014, https://www.icij.org/investigations/offshore/sun-and-shadows-how-island-paradise-became-haven-dirty-money/. ↩

-

Seychelles election: Wavel Ramkalawan in landmark win, BBC News, 25 October 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-54681360. ↩

-

Opposition candidate wins Seychelles presidential election, Africanews, 25 October 2020, https://www.africanews.com/2020/10/25/opposition-candidate-wins-seychelles-presidential-election/. The 2020 World Press Freedom Index ranked Seychelles 63rd out of 180 countries. The report highlighted that ‘media pluralism and funding is limited by this small archipelago’s size and population. The self-censorship reflexes inherited from decades of communist single-party rule and close control of the media is gradually dissipating and giving way to a broader range of opinion and more editorial freedom.’ Reporters Without Borders, 2020 World Press Freedom Index, https://rsf.org/en/seychelles. ↩

-

Patsy Athanase, President Wavel Ramkalawan sworn in after sea-change election for Seychelles, Seychelles News Agency, October 26, 2020, http://www.seychellesnewsagency.com/articles/13768/President+Wavel+Ramkalawan+sworn+in+after+sea-change+election+for+Seychelles. ↩

-

See the assessment of the Seychelles on the ENACT Organised Crime Index for Africa, 2019, https://ocindex.enactafrica.org/country/Seychelles. ↩

-

Figures for 2019 reported by APDAR and cited by the BBC: Kanika Saigal, Why Seychelles has the world’s worst heroin problem, BBC, 21 November 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-50488877; Addiction in paradise: Seychelles battles heroin crisis, France 24, 20 February 2020, https://www.france24.com/en/20200220-addiction-in-paradise-seychelles-battles-heroin-crisis. ↩

-

Interview with Yvana Theresine, APDAR representative, Providence, Seychelles,12 March 2021; phone interview with Dereck Samson, ANB spokesperson, 10 March 2021; interview with representatives of DURNS, March 2021. ↩

-

Interview with former drug user and member of DURNS, 16 June 2020. ↩

-

Interview with an opposition party activist, 14 July 2020. ↩

-

Interviews with: Mr. Raymond Saint-Ange, superintendent of prison services; Mr. Samir Ghislain, deputy superintendent; and Ms. Elsa Nourrice, principal probation officer and head of prison rehabilitation service, 26 May 2020. ↩

-

One higher-level former officer described a culture within the ANB of falsely reporting on officers who are not corrupt to obstruct their career progression, interview with a former army and police officer, 26 June 2020. The ANB was uniquely identified in this respect by other sources in the Seychelles criminal justice system: Interview with Mr. Raymond St. Ange, superintendent of prison services, Mr. Samir Ghislain, deputy superintendent; and Ms. Elsa Nourrice, principal probation officer and head of prison rehabilitation service, 26 May 2020; interview with representatives of the Anti-Corruption Commission Seychelles, 16 June 2020; interview with a former police officer, Victoria, Mahe, 16 June 2020. ↩

-

Interview with PWUD, John (name has been changed), Seychelles, March 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with PWUD, Seychelles, in June–August 2020 and March 2021. ↩

-

See DURNS Facebook page for more information on the organization: https://web.facebook.com/527853034001307/posts/1686112008175398/?_rdc=1&_rdr. ↩

-

Interview with representatives of DURNS, March 2021. ↩

-

Interview with Raymond St. Ange, Victoria, Seychelles, 11 March 2021. ↩

-

Created in response to the Anti-Corruption Act passed in 2016, the ACCS is mandated to investigate and prevent corruption in the public sector. The commission reported that preparations are under way to hand over the first cases to the attorney general for prosecution. ↩

-

Information shared by ACCS, by email, March 2021. A spokesperson for the ANB declined to comment on whether the new administration was putting an increased focus on corruption (telephonic interview with Dereck Samson), 10 March 2021. ↩

-

Telephonic interview with Clive Camille, 18 March 2021. ↩

-

Luciana Sophola, Citizen Engagement Platform (CEPS) office, Orion Mall, 12 March 2021. ↩

-

The EU now lists 12 nations owing to concern that their policy environments support tax fraud or evasion, tax avoidance and money laundering. The EU’s decision followed that of France adding the Seychelles to its own list some months before. Seychelles named to EU’s tax-haven ‘blacklist’, Africa Times, 20 February 2020, https://africatimes.com/2020/02/20/seychelles-named-to-eus-tax-haven-blacklist/. ↩

-

Council of Europe, Taxation: EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions, accessed 17 March 2021, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/eu-list-of-non-cooperative-jurisdictions/. ↩

-

The amended legislation includes: Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters (Amendment) Act 2021; Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism (Amendment) Act, 2021; International Trust (Amendment) Act, 2021; Prevention of Terrorism (Amendment) Act, 2021; Beneficial Ownership (Amendment) Act, 2021. Available at: https://www.gazette.sc. ↩

-

Statement on the Transparency International Seychelles Facebook page, 17 March 2021, https://web.facebook.com/tiseychelles/posts/1576367302562499. ↩

-

Interview with PWUD, Thomas (name has been changed), Seychelles, March 2021. ↩

-

Interview with PWUD, Jane (name has been changed), Seychelles, March 2021. ↩

-

LDS 2020 General Elections Manifesto, p. 8 and p. 17, available at: https://lds.sc/images/2020/PDF/Manifesto–LDS-25th–September-2020–Web-version.pdf (accessed 13 April 2021). ↩

-

Interview with representatives of DURNS, March 2021. ↩

-

Interview with representatives of DURNS, March 2021. ↩

-

Interview with PWUD, Jane (name has been changed), Seychelles, March 2021. ↩