Nelson Mandela Bay is an often-overlooked example of rampant gangsterism.

Watching over their turf. The Nice Time Bozzas are caught on camera in Helenvale, an urban area that is contested by some 20 gangs.

Photo: © Corinna Kern/laif

When the international media cover gang violence in South Africa, the focus is overwhelmingly on Cape Town. This is not without reason: using homicide rate as a proxy for general violence levels, Cape Town holds the title of most violent city in South Africa.1

However, it does not stand alone. Some suburban communities in South Africa are now regularly experiencing similar levels of violence, yet these do not necessarily receive the same levels of notoriety.

Nelson Mandela Bay metropolitan area – comprising Port Elizabeth and a number of surrounding towns in the Eastern Cape Province – is home to many of these communities. Traditionally a blue-collar port area with an economy centred around car assembly and manufacturing, in recent years Nelson Mandela Bay has been experiencing a steady increase in violence. Our research has examined the specific local factors that have driven Nelson Mandela Bay to become one of the most violent places in South Africa.

Violence in Nelson Mandela Bay

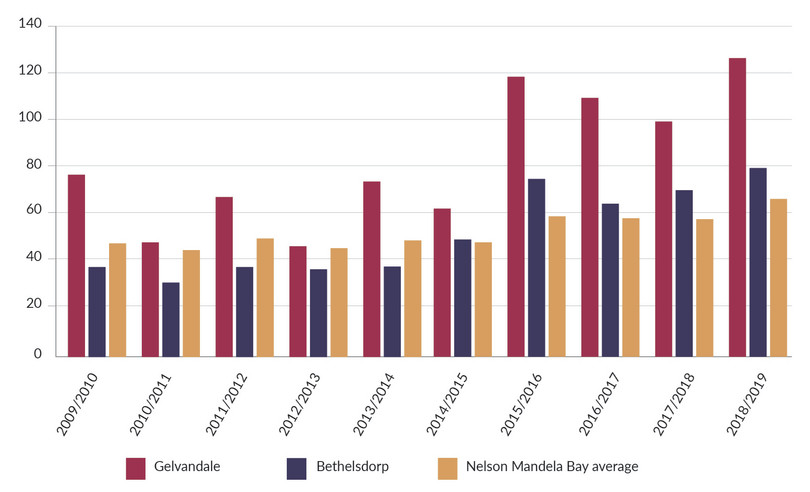

In 2017/2018, Nelson Mandela Bay had just over 500 recorded murders, with a homicide rate of just over 55 per 100 000 residents. Violence is concentrated in particular neighbourhoods to an even greater degree than Cape Town or Johannesburg. In Bethelsdorp and Gelvandale – two of the worst-afflicted areas – levels of reported homicide are staggeringly high. In 2018/2019, Bethelsdorp had 79 homicides per 100 000 people, while Gelvandale saw 124 homicides per 100 000. By comparison, no subnational area in Central America (considered by criminologists to be the most criminally violent region on Earth) exceeds 90 homicides per 100 000 of the population.2

In both Nelson Mandela Bay and parts of Cape Town, racial and economic marginalization, extreme poverty, high rates of youth unemployment, the presence of organized-crime groups and failing government responses shape communities’ lives and drive violence. There are, however, important differences between the two. While both cities’ murder rates peaked in 2006/2007 and then declined to 2010/2011, their trajectories then diverged. While violence in Cape Town spiralled upwards to around 70 deaths per 100 000 in 2017/2018, Nelson Mandela Bay’s stabilized at a high level for several years before increasing rapidly in 2015/2016, a period in which there was extensive gang-related violence in the city. The latest official figures (2018/2019) suggest that the city’s murder rate is now above 60 cases per 100 000 residents, edging closer to Cape Town.

Our research in Nelson Mandela Bay has found that specific patterns of gang activity and emerging patterns of misgovernance are crucial to understanding the violence in the metropolitan area, both how it has increased so dramatically and how it differs to gang violence in Cape Town and elsewhere in South Africa.

Figure 3 Comparative homicide rates for Bethelsdorp, Gelvandale and Nelson Mandela Bay, 2009/2010 to 2018/2019. Bethelsdorp and Gelvandale are two of the worst-affected areas for gang violence in the metropolitan area.

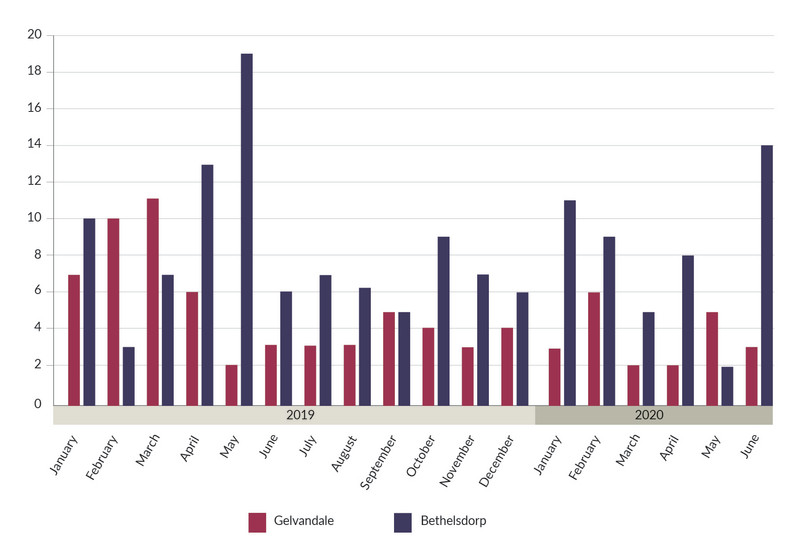

Figure 4 Gang-related murders in Gelvandale and Bethelsdorp, 2019 to June 2020.

Luchen Pieterse, 5, was killed, reportedly caught in the crossfire of a gang shoot-out, while flying his kite on the streets of Helenvale in March 2014.

Photo: GI-TOC

Gemors gangsterism and building legitimacy

One distinctive pattern of gang violence observed in Nelson Mandela Bay, particularly in the northern parts of the city, is what has become known as gemors (‘messy’ or ‘trashy’) gangsterism.3 This is violence directed indiscriminately at ordinary citizens, either for robbery or simply to spread fear.4 This subverts the traditional use of violence by gangs for instrumental purposes, such as consolidating territory, enforcing agreements between gangs or revenge killings.5

Many of the perpetrators of gemors gangsterism are young children between the ages of 9 and 14 who are paid for their actions with small quantities of drugs. Because the primary motive mainly seems to be the drugs,6 rather than any economic motive or the loyalty and belonging that attracts children to ‘traditional’ street gangs, child gang members can be hired with ease, with neither gang hierarchy nor a sense of loyalty keeping them in check.

However, while some gangs have spread violence and instilled fear in the community, others often provide income, protection and services that would usually be supplied by the state. Gangs in Nelson Mandela Bay have reportedly purchased school uniforms for people in the community, paid for electricity, medicines and diapers and distributed food parcels.7 By taking on the provision of such services, gangs seek to garner legitimacy at the expense of local government.

Criminal control over business: gangs, tenders and hits

There are persistent allegations that some gangsters in Nelson Mandela Bay have made moves to capture local government contracts as a means to extract ‘rents’ from state business.8 This practice brings armed and violent actors into the arena of local politics – actors who are prepared to use violence to maintain their business interests and who enter into corrupt arrangements with local politicians. It also affords some veneer of legitimacy to criminal enterprises which are presented as legitimate businesses and recipients of public funds.

One interviewee – a police detective with knowledge of gang activities – said: ‘Gang bosses have [registered] SMMEs [small, medium and micro-enterprises] and they have relationships with powerful politicians like ward councillors and maybe even high up … That gangster that is operating like a businessperson still is the head of the gang and has all of his minions that are ready to kill for him because those kids are armed to the teeth with guns.’9

A former gang member claimed that gang meddling in lucrative government contracts could be traced to the early years of South Africa’s democracy: ‘The gangsters found that they could extend their violent extortion rackets to manipulate control over council members by registering as SMMEs. … Politicians were forced to succumb to gang bosses under the threat of violence.’10

Violence and murders related to government tenders reached an all-time high in 2019, when several homicides were linked to a tender for cleaning storm-water drains in the Nelson Mandela Bay metropolitan area.11 Lungelo ‘Baba’ Ningi, the leader of the Eastern Cape Black Business Caucus (a group apparently committed to the development of black entrepreneurs and business interests in the province), and businessman Nkululeko Gcakasi were two of the victims.12 Ningi had been vocal in his support for local SMMEs but had also been accused (just weeks before his murder) of siphoning off money for himself.13 It is also alleged that the Black Business Caucus was influential in the irregular allocation of funds in the tender process of the contract for storm-drain cleaning.14

Gelvandale community residents gather during a march against violence and gangsterism in the area, August 2017.

Photo: © Gallo Images/Die Burger/Lulama Zenzile.

At the time of writing, some R4 million (US$260 000) from the storm-water project is still unaccounted for.15 The former mayor of the metropolitan area, Mongameli Bobani, had opposed a forensic audit into the project, feeding suspicions that there may be involvement from the top tiers of local government.16

Politicians may also look to benefit from the services offered by the gangs. As a police officer from Nelson Mandela Bay explained: ‘The ward councillor or the high-level politician that [arranged] a tender for the gang boss also can have his wish granted in terms of the gang boss doing him a favour. The ward councillor or politician maybe has an enemy in politics and then they go to the gang boss and say, “I helped you get this tender and I gave your people this and that, so sort out this rival councillor for me.”17

The result is a governance crisis whereby state functions at the local level are usurped by criminal actors while violence spirals on several fronts, from political hits to unpredictable gemors gangsterism. As a result, swathes of Nelson Mandela Bay’s population are living under conditions of criminal governance. Nelson Mandela Bay deserves urgent attention, but overshadowed by Cape Town, may struggle to receive it.

This report draws from research in a new GI-TOC ESA – Obs research report, A city under siege: Gang violence and criminal governance in Nelson Mandela Bay, which is the culmination of extensive interviews with community members, gangsters and government. The report highlights how Nelson Mandela Bay has been emerging as one of South Africa’s major centres of gangsterism for many years, even though this has received little attention from national and international civil society. We advocate for a more coherent strategy to break the cycle of violence, roll back criminal influence in local authorities and erode the barriers of exclusion that separate communities in the city.

In order to advocate for and discuss effective policy responses, on 4 November 2020, GI-TOC board member Vusi Pikoli, South Africa’s former National Director of Public Prosecutions, led a closed briefing in Nelson Mandela Bay with a high-level group including members of lawenforcement, prosecution and government departments in the Eastern Cape, as well as academics.

The closed briefing enabled all stakeholders to openly engage with the distressing issues raised by the report. These included, among others, corruption and misgovernance in the city’s administration, policing shortcomings and the prevalence of gemors gangsters.

Notes

-

In 2017/2018, Cape Town had a total of just under 2 500 murders, at a rate of about 70 murders per 100 000. In comparison, Nelson Mandela Bay had just over 500 recorded murders in that year, with a homicide rate per 100 000 residents of just over 55. Both cities are well above the average murder rate for South Africa as a whole, which stands at 33 per 100 000. The crime figures for each of the cities are drawn from official police figures but differ from them, as they have been recalculated taking into account both the boundaries and populations of the metros. Police figures are generally reported by police areas, which do not necessarily match the boundaries of local government. ↩

-

See Deborah J Yashar, Homicidal Ecologies: Illicit States and Complicit States in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. See also Maria Alejandra Navarrete and Anastasia Austin, Capital Murder: 2019 Homicide Rates in Latin America’s Capital Cities, Insight Crime, 5 March 2020, https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/2019-homicides-latin-america-capital/. ↩

-

Kim Thomas, Mark Shaw and Mark Ronan, A city under siege: Gang violence and criminal governance in Nelson Mandela Bay, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, November 2020, p 21, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Gang-violence-and-criminal-governance-in-Nelson-Mandela-Bay.pdf. ↩

-

Interviews with a community leader who serves as a mediator between gangs, Port Elizabeth, March 2019. ↩

-

See J Olivier and P W Cunningham, Gang violence in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, Commonwealth Youth and Development, 2, 1, 2004, 75–105. ↩

-

PE gang war could settle election score, Mail & Guardian, 15 July 2016, https://mg.co.za/article/2016-07-15-pe-gang-war-could-settle-election-score. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with a community member in Gelvandale, March 2019. ↩

-

Interviews with a police detective conducted in Cleary Park, Port Elizabeth, September 2018. ↩

-

Interview with a former gang member in Bethelsdorp, Port Elizabeth, September 2018. ↩

-

The tender was awarded in December 2018 and valued at R21 million. This equates to roughly US$1.15 million (calculated according to May 2020 exchange rates). See Mpumzi Zuzile, Stormwater drain tender sparks rash of killings in PE, Sunday Times, 24 February 2019, https://www.timeslive.co.za/sunday-times/news/2019-02-24-listen–stormwater-drain-tender-sparks-rash-of-killings-in-pe/. ↩

-

Hendrick Mphande, Eastern Cape Black Business Caucus leader shot dead during argument, Times Live, 28 January 2019, https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2019-01-28-eastern-cape-black-business-caucus-leader-shot-dead-during-argument/. ↩

-

Michael Kimberly and Nomazima Nkosi, ‘Give us the money’: SMME forum leader accused of living large while business owners wait to be paid, The Herald, 15 January 2019. ↩

-

Michael Kimberly and Nomazima Nkosi, Did this spark SMME killings?: Report shows millions unaccounted for in messy drain-cleaning deal, Herald Live, https://www.heraldlive.co.za/news/politics/2019-02-06-did-this-spark-smme-killings/. ↩

-

ANA Reporter, Place ‘coalition of corruption’ under administration – DA, The Citizen, 24 April 2019, https://citizen.co.za/news/south-africa/politics/2122628/place-coalition-of-corruption-nelson-mandela-bay-under-administration-da/. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with former SMME owner, August 2019, by phone. ↩