Gold and guns: audacious armed robberies at gold-smelting facilities in South Africa.

On 10 March 2020, a gang of 20 armed men stormed a gold plant 140 kilometres west of Johannesburg operated by Village Main Reef (VMR), a Chinese-owned mining company. Hijacking a front-end loader, the gang overturned an armoured vehicle and broke through the wall of a smelt house. According to industry sources, the gang made off with an undisclosed amount of calcine, the gold-bearing material from which bars of bullion are processed. VMR confirmed that the episode took place but declined to comment as the incident was under investigation.1

The attack was an audacious example of the spate of armed heists that have targeted gold smelters in South Africa since 2018. The gangs are armed with automatic assault rifles, with 15 to 30 gunmen typically involved in an attack. In the view of some security analysts, the gangs’ methods – including cutting power to take out CCTV cameras, the taking of hostages and the use of explosives in some cases to blow through perimeters – suggest that they have recruited former members of the police and armed forces or ex-private security personnel.2

Even unsuccessful attacks may be an indication of a highly tactical approach. ‘Some of the attacks are done to test the security, to see how the mine security reacts and the timing of their response,’ said Louis Nel, a mine-security consultant. ‘There is a reason behind their madness. [T]hey will launch an attack, they fail in their objective, then months later the successful one will happen.’18 A security executive with a Johannesburg mining house (who asked not to be named) said that this appeared to be the case with two failed assaults at his company’s operations in 2019. ‘The second time they clearly had a better understanding of our reaction times.’3

Both the mining companies and the gangs are constantly adapting their methods to outflank one another – the March assault was the first time that heavy machinery had been used to smash through a wall. ‘Companies are also learning and are no longer parking loaders by the smelter walls,’ said the mine- security manager.4

Wreckage of a mining-security armoured personnel carrier that was set alight by attackers at a Sibanye Gold facility.

Photo: Sibanye Gold Ltd

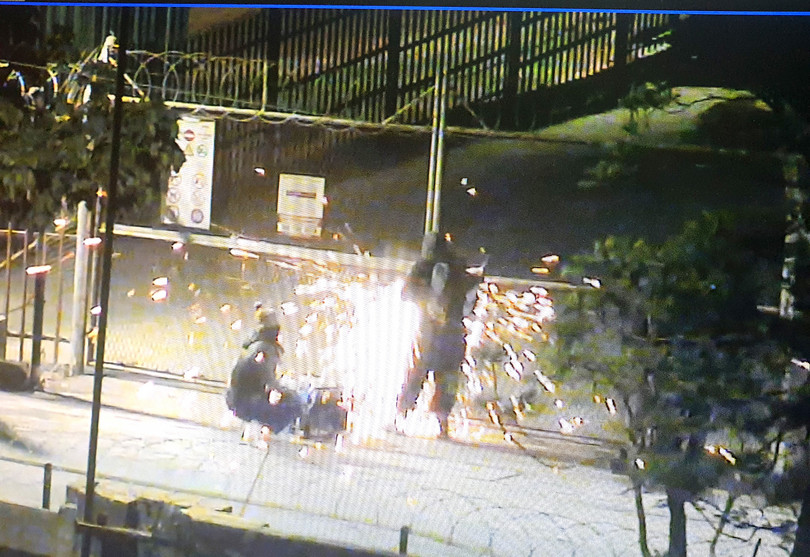

Thieves break open a security gate at a gold facility in South Africa.

Photo: Supplied

The 2019 surge

According to the Minerals Council South Africa, an industry group, there were 19 attacks on gold facilities in 2019, up from five in 2018 (attacks were sporadic before 2018). This may be an underestimate, as not all companies report such incidents to the council, particularly smaller producers who are not council members, according to Nel.5 The Minerals Council acknowledges the theft of more than 100 kilograms of gold, but not all companies have disclosed their losses.6 Companies are also unwilling to acknowledge publicly that attacks have taken place at their facilities.

Several notable attacks in late 2019 resulted in mining companies bolstering their security to dissuade gangs. In December 2019, global miner Gold Fields suffered an attack at its South Deep mine in Gauteng province.

Fifteen armed men stormed the operation and made off with gold worth about US$500 000 from the smelting plant.7 Gold Fields spokesperson Sven Lunsche said the company has subsequently put in place additional security measures at a cost of around US$2 million: ‘We are completely enclosing the mine with a perimeter wall and this should be in place by the end of the year.’8 Surveillance systems have also been upgraded.9

DRDGold, a mid-tier gold producer, was also hit in late 2019 and an employee was killed in the attack.10 In an emailed response to questions, the company said that ‘one arrest was made and the individual was charged with murder and armed robbery. About half of the 12–15kg of calcine concentrate stolen was recovered at the home of the individual who was arrested.’ DRDGold has since spent about US$700 000 on security enhancements, including the acquisition and application of surveillance and other technology.11

This is one of only three arrests that the GI-TOC have been able to confirm in connection with such incidents; Harmony Gold says that two suspects were arrested in connection with a heist at its Kalgold mine in December 2019.

The scarcity of arrests poses a problem for law enforcement, as intelligence gathered from arrests may help thwart other attacks.12 However, mining executives and security personnel believe the police forces in mining areas are compromised.13 Collusion includes tipping off illegal miners and the heist gangs to intelligence developments, turning a blind eye to their activities, ‘losing’ dockets so cases are thrown out and failing to act on information that could lead to arrests.14 ‘Getting intelligence from arrested suspects is very much crucial to preventing such attacks,’ said one mine security official. ‘Unfortunately the cops often don’t know how to gather more intelligence or they don’t act on it.’15

Mine-security consultant Nel likewise confirmed the shortfall in police capability: ‘The police are part and parcel of the problem. There was a gold and diamond unit formerly in the police but it no longer exists and so the police have lost that investigative capability.’16 But the mining companies are applying pressure to change the situation. According to one mining executive: ‘There are lots of allegations of corruption in the police in those areas and so the industry is talking with the South African Police Service to reinstate the specialized mine police unit.’17

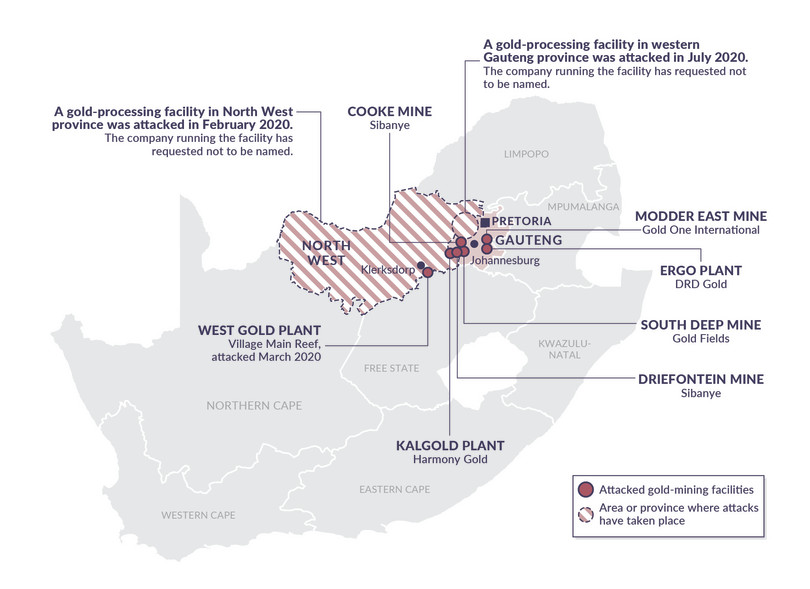

Figure 2 South African gold-processing facilities targeted by armed gangs, 2018–2020.

Figure 3 Comparison of frequency of reported incidents of cash-in-transit heists, bank robberies and robberies at gold facilities in South Africa.

Note: According to Minerals Council South Africa, robberies at gold facilities were sporadic prior to 2018. The GI-TOC have been able to confirm three robberies at gold-processing facilities in 2020, yet this may be an underestimate as mining companies are often unwilling to acknowledge that robberies have taken place at their facilities.

Source: South African Police Service

Armed gangs switch markets

The surge in 2019 has been attributed to a number of factors. Gold prices, in dollar terms, rose over 17% over the course of 2018 and 2019 to more than US$1 500 an ounce.18 The surge has also been associated with a decline in hits on armoured vehicles transporting cash – known as ‘cash-in-transit’ heists.19 Among other initiatives, security cooperation between affected businesses and new technologies that coat the vault of the vehicle with a fast-drying foam during an attack have been credited with the reduction in the number of cash-in-transit heists.20 In the 2018–19 financial year – when gold heists became a major phenomenon – cash-in-transit heists declined over 23% according to police statistics, from 238 to 183.21

Security experts believe that some of the cash-in- transit heist gangs subsequently turned their attention to gold. The same weapons are used in both kinds of heists (including the use of explosives to blow vaults open).22 Geographically, the cash-in-transit heists have also been concentrated in Gauteng province, South Africa’s industrial hub, near where the bulk of the gold attacks have taken place.23

‘It’s big groups [involved in cash in transit heists] just like the gold attacks with sophisticated weapons. We strongly suspect there is overlap between the gangs,’ said the Johannesburg mine-security official. He also said such gangs are suspected to have been involved in bank robberies, but the massive increase in security at banks – from CCTV cameras and increased security staff to marked notes and other initiatives – have gradually cut off that once-lucrative revenue stream. (There has been a dramatic decline in bank robberies in South Africa since 2010.)24 ‘They [the gangs] operate on a risk model like any other enterprise. High reward, low risk. Risk gets too high and the reward too low then it’s time to change their business model.’

The rise in gold attacks also followed drives in 2017 by gold producers to remove groups of illegal miners from their operations. Initially this yielded some success,25 which may have had the inadvertent consequence of forcing the illegal-mining networks to find new sources of revenue. The foot soldiers used in these two spheres of criminal activity are different: illegal miners, known as zama zamas (a Zulu term that roughly translates as ‘take a chance’), are often migrant workers from neighbouring countries such as Lesotho and Mozambique who have often previously worked in the mines, in contrast to the security background suspected for the heist gangs. The illegal miners require equipment and supplies as they can spend months underground, while the heist gangs require arms and vehicles. However, the buyers of the gold are the same and the groups funding these operations are suspected to have links with one another.26

‘The criminal gangs are diversifying. Twenty years ago a gang would target gold or diamonds but now they are involved in different commodities and different areas,’ said another mining-security official, remarking that there are now links between several illicit-commodity trades including gold, chrome, copper and rhino horn.27 Other security and industry sources interviewed for this article agreed that this was the case. ‘A gang might say, “We can do cash in transit but we can’t smelt gold. So let’s combine forces,”’ said one.28

The destination of South African gold

Regardless of its origin – be it pried from the ground by an illegal miner or stolen at gunpoint – gold flows through the same laundering channels, with Dubai, India and China the main destinations. ‘They [the gangs robbing gold in heists] take the concentrate, they process it to gold and then sell it through the normal channels, the same ones that the zamas [illegal miners] use,’ said Nel.29

These ‘channels’ include second-hand jewellery shops and gold dealers in South Africa where it becomes ‘legitimate’ for purposes of resale. According to a former police investigator, some vendors even use illicit gold to fraudulently claim Value Added Tax refunds: ‘The buyers purchase the illicit gold, it is unwrought and they need to get it in the system. They buy it, throw it into a big pot and melt it, and then they take it to a refinery and present it as second-hand gold. They then claim VAT and they often make more money on that than on the gold.’30

Alternatively, gold is simply smuggled out through South Africa’s airports and shipping ports. ‘We are convinced that through our airports and through our shipping ports these unrefined gold bars make their way to Dubai, China and India,’ said one mine-security official. ‘Two years ago, India strengthened its controls on gold coming into the country, and we are not sure how the criminals have got around that. But as far as China and Dubai are concerned, we are given to understand gold still flows quite freely into those jurisdictions where it is then laundered into the legitimate market.’31

Figure 4 Frequency of cash-in-transit heists in South Africa, 2019 and 2020. SOURCE: South African Banking Risk Information Centre.

Shifts caused by the pandemic

Security sources say the frequency of attacks on gold facilities has declined since South Africa imposed COVID-19 lockdown restrictions in late March. Interestingly, cash-in-transit heists have spiked again from July to October, according to data shared by the South African Banking Risk Information Centre. Whereas between March and June cash in transit heists had declined compared to 2019, from July there was a 69% increase compared to July 2019, which rose to a 122% increase on the previous year in the 1–23 October period. The increase has been particularly marked in Gauteng, where 102 incidents have been reported compared to October 23, compared, to 53 in 2019, a 92% increase.32

SBV Services, a company that provides security services to the cash-in-transit sector, also confirmed this was the case, saying it was ‘extremely concerned about the increase in frequency of these attacks’. The company also said technologies used to protect its employees on the road and the assets they protect was continually evolving. And the Times Live news site reported on 19 October that data from the South Africa Banking Risk Information Centre shows a 29% increase in cash van attacks between 2019 and 2020.33

‘You see a focus on one source of contraband, then a switch to another when obstacles are thrown up,’ said one security source. When cash-in-transit heists became more challenging because of the security measures employed, the focus turned to gold facilities. But then gold-mining companies ramped up their security, funded in part by the high price of gold.34 The GI-TOC has been able to confirm only three attacks on gold facilities in 2020: the VMR incident mentioned above, and two more in February and July. (In both these cases, the company involved has requested not to be named.)35 A security source with the company involved in the July incident described a sophisticated attack: ‘They took out the power so the CCTV went down. The intruders took a plant operator hostage [but] there was no gold in any form in the smelt house. Luckily there was no gold in the facility at the time.’36

But with gold’s price near record highs – hitting over US$2 000 an ounce in August 2020 – there are concerns that attacks on gold facilities could spike again, once the heist gangs have figured out how to bypass the new security measures.37 The developments seen in the relative frequency of gold heists, cash-in- transit heists and bank robberies since 2018 illustrate that these groups’ sophisticated tactics can be adapted to new vulnerable targets.

Notes

-

Interview with mining executive, Johannesburg, 5 October 2020; interview with mine-security executive, Johannesburg, 9 October 2020; email correspondence with Village Main Reef, 9 October 2020. ↩

-

Interview with mine-security executive, Johannesburg, 9 October 2020. ↩

-

Interview with mine-security executive, Johannesburg, 9 October 2020. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with Louis Nel, Johannesburg, 7 October 2020. ↩

-

Email correspondence with Minerals Council South Africa, 12 October 2020. ↩

-

Email correspondence with Gold Fields spokesman Sven Lunsche, 5 October 2020; Felix Njini, Gold mine gangs tote AK-47S to outgun South African police, Bloomberg, 2 February 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-02-02/gold-mine-gangs-tote-ak-47s-to-outgun-south-african-police. ↩

-

Email correspondence with Gold Fields spokesperson Sven Lunsche, 5 October 2020. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Email correspondence with DRDGold. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Email correspondence with Harmony Gold ↩

-

Interview with Louis Nel, Johannesburg, 24 July 2020; interview with Nash Lutchman, head of security, Sibanye- Stillwater, 18 September 2020, via Zoom. ↩

-

Ibid; interview with mine-security executive, 24 July 2020, via Zoom; Interview with mine-company executive, Johannesburg, 24 July 2020. ↩

-

Interview with mine-security executive, Johannesburg, 13 October 2020. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with mine-company executive, Johannesburg, 24 July 2020. ↩

-

World Gold Council data, https://www.gold.org/goldhub/data/gold-prices. ↩

-

Interview with mine-security executive, Johannesburg, 9 October 2020; interview with security executive at another mining company, 25 July 2020. ↩

-

Email correspondence with SBV Services, 13 October 2020; Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, https://www.csir.co.za/foiling-cash-transit-heists. ↩

-

South African Police Service, Crime Statistics: crime situation in Republic of South Africa twelve (12) months (April to March 2018_19), https://www.saps.gov.za/services/april_to_march2018_19_presentation.pdf. ↩

-

Interview with mine-security executive, Johannesburg, 9 October 2020. ↩

-

Ibid., and follow-up interview, 14 October 2020. ↩

-

Interview with mine security executive, Johannesburg, 9 October 2020. ↩

-

Ed Stoddard, Sibanye says clears most illegal miners 21 from gold shafts, Reuters, 26 February 2018, https://fr.reuters.com/article/us-sibanye-illegalminers-exclusive-idUSKCN1GA0I2. ↩

-

Interview with mine-security executive, Johannesburg, 9 October 2020; interview with security executive at another mining company, 25 July 2020. ↩

-

Interview with security executive at another mining company, 25 July 2020. ↩

-

Interview with mine-security executive, Johannesburg, 9 October 2020. ↩

-

Interview with Louis Nel, Johannesburg, 7 October 2020. ↩

-

Interview with unnamed former police investigator, 27 July 2020. ↩

-

Interview with mine-company executive, Johannesburg, 24 July 2020. ↩

-

Email correspondence with SABRIC, 26 October 2020. ↩

-

Email correspondence with SBV Services. ↩

-

Interview with mine-security executive, Johannesburg, 9 October 2020, and follow-up interview, 13 October 2020. ↩

-

Email correspondence with companies and interview with mine-security executive, 25 July 2020, via Zoom. ↩

-

Interview with mine-security executive, 25 July 2020. ↩

-

Interview with mine-security executive, Johannesburg, 9 October 2020. ↩