The use of gangs by politicians in election campaigns in Mombasa is just one aspect of the role gangs play in Kenyan politics.

Criminal gangs have an entrenched and insidious role in Kenya’s political landscape. This was clearly shown in the post-election violence in 2007, where more than 600 000 people were displaced and more than 1 000 killed across the country in inter-ethnic attacks, in which criminal gangs were key instigators of violence. Yet the gang phenomenon has a decades-long history and is still widespread today.

In Mombasa, as elsewhere in Kenya, gangs are used as an unofficial campaigning resource in the run-up to elections to intimidate rivals (and rivals’ voter bases), provide ‘security’ at rallies, and even eliminate rivals. The deployment of gangs around elections is just one aspect of the wider set of quid pro quo relationships between gangs and politicians across the country.

Bedzima and the elections

The role of ‘political figures’ in funding gangs is often discussed in Kenyan media and among civil society. However, it is rare that individual politicians are held accountable. The career of Rashid Bedzimba, former MP for Kisauni (a suburb of Mombasa), is a notable exception to this rule: allegations against Bedzimba have been publicly aired, and several gang members corroborated these allegations in interviews with the GI-TOC.

Bedzimba, 54, is a former police officer. He left the force in 1992 to enter politics as an election-campaign manager in Mombasa.1 After stints as a county councillor and a member of the County Assembly for Mjambere Ward, Kisauni, he won the parliamentary seat in 2013 after the incumbent, Hassan Joho, decided to run for the Mombasa governorship.2

In the 2017 general elections, Bedzimba lost his seat to businessman Ali Mbogo, whose campaign highlighted allegations that Bedzimba had used criminal gangs to secure his own election four years before, and used a slogan that referenced the gang in question. After the 2017 election, Joho employed Bedzimba as his political adviser, and Bedzimba remains a powerful individual in Kisauni.3

The allegations around Bedzimba claimed that he was linked to Wakali Kwanza, the most prominent criminal gang in Mombasa. As well as being associated with political thuggery, the gang is implicated in street robberies and burglaries, and is present across Mombasa in Kisauni, Nyali, Likoni and the north and south sides of Mvita (Mombasa’s central island). Wakali Kwanza – literally meaning ‘the first tough ones’ in Kiswahili – was initially a popular football club funded by an MP using Constituency Development Funds.4

A member of Wakali Kwanza told the GI-TOC that he had been recruited into the gang at the age of 15 during an election campaign and that recruits were each paid 1 000 Kenyan shillings (Ksh) – about US$10 – to disrupt the events of Bedzimba’s rivals, which included ‘causing chaos, stealing and beating people at events’.5 A senior figure in a major trade association with close links to the political elite claims that Bedzimba and two other politicians had adopted this tactic.6 In the run-up to the election, the then Coast Regional Coordinator, Nelson Marwa, said wealthy and influential individuals financed Wakali Kwanza, and that they were being paid Sh500 each (about US$5) ‘to go on operations.7

After being attacked at a funeral in 2016, Mbogo publicly linked Bedzimba to the Wakali Kwanza and Wakali Wao gangs.8 Bedzimba strongly denied these allegations: ‘If I hear anyone associating me with those gangs, I will require that they prove their allegations in court. As a leader, my focus is on serving my people … If the police have information about these gangs, they should arrest and take them to court.’9 In June 2017, Mbogo was again attacked by a gang and claimed that the men had been sent by a rival, but after Mbogo’s election win the situation turned on its head, with Bedzimba filing a petition in which he accused Mbogo of violence, voter bribery and intimidation of his agents.10

Beyond Bedzima: Gangs as part of Mombasa’s political landscape

The allegations surrounding Bedzimba’s use of gangs to intimidate his rivals seem to be typical of the use of gangs by politicians in Mombasa. One MP, who has hired gangs on several occasions to guard his rallies from rivals, described the situation: ‘Normally, in political areas where the election is too close to call, where the stakes are very high, violence during campaigns is apparent. My constituency is hot because we always have powerful people run. Here, tactics, and not necessarily ideology, matter. You have to defend your supporters from intimidation and thuggery.’11

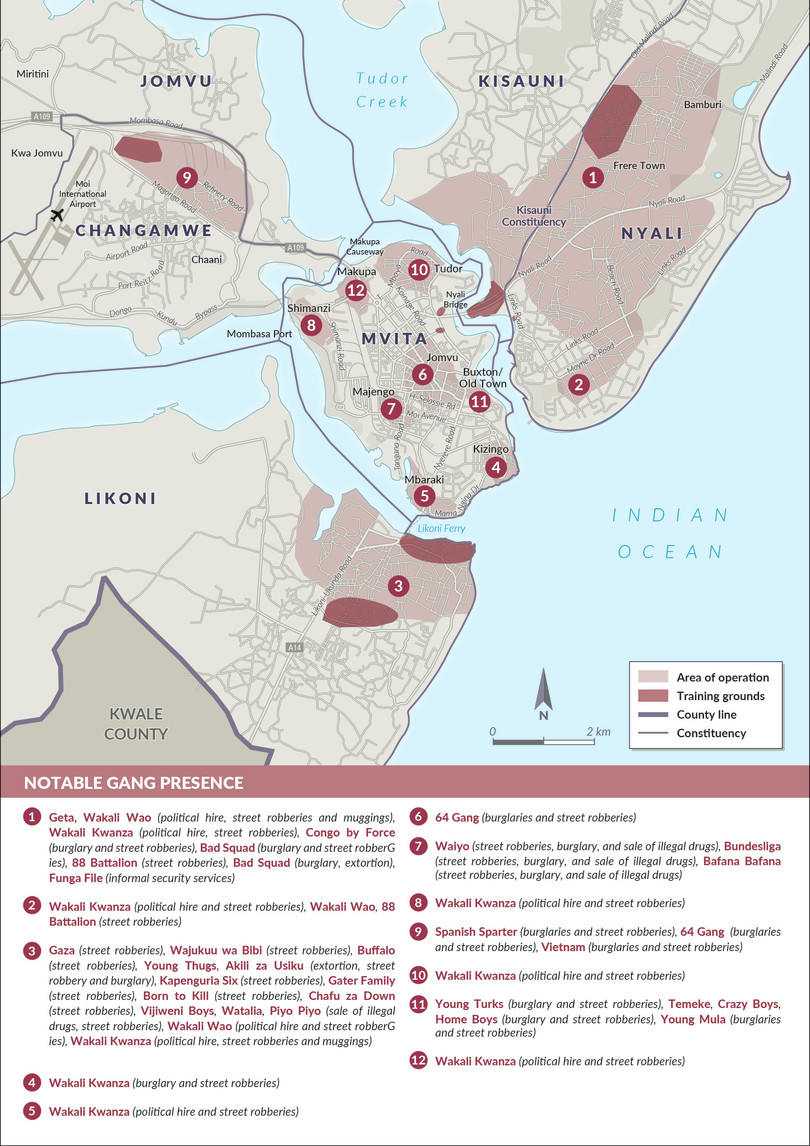

Figure 1 Gang presence in Mombasa County

Note: The gangs presented here represent some of the most notable gangs according to their level of influence and violence, and the scale of operations. These designations are derived from interviews with the police, gang members, media reports and state reports. The map is based on ward boundaries derived from government documents, as well as Google Maps where government sources were contradictory. We have tried to ensure constituency boundaries are as accurate as possible, but some borders may be inexact.

Mohamed Ali, MP for Nyali, an affluent suburb in Mombasa, also acknowledged the role of gangs in the political process: ‘Some of these criminal groups are sponsored by politicians to frustrate rivals. I do not support these stupid criminals.’12

Gangs appear to be trained and organized on behalf of the politicians who hire them. One man, who had once been in the Kenyan Defence Force and was later a member of a criminal group that stole cars and drove them over the border to Tanzania, described working as a trainer for Wakali Kwanza during the 2017 elections. He said he was hired, by a campaign manager of an MP, along with other men – a mix of gangsters and former police officers – to train gang members on a beach in the Mishomoroni area of Mombasa. He was also later hired to ‘cause trouble to show that the community suffers if his patron is not the MP’ after the MP lost the election. Although current Kisauni MP Ali Mbogo was not the MP hiring him for this work, he also accused Mbogo of establishing a gang.13

In return, gangs may be able to call upon their patrons for protection from arrest following the election. Francis Auma, a civil-society activist working in gang- affected areas and monitoring police stations, said ‘if anyone is arrested, the first person to be called is the local politician to have them released. It happens all the time, not just during the election period.’14 Some gang members have also been rewarded with positions in Mombasa County’s government, where they can draw salaries.

Generally, however, the relationship with political figures does not translate into material support outside of the election-campaign period. This means that violence often spikes in the periods between election years as gangs turn to attacking the public to finance themselves in lieu of political work. Hezron Awiti, a former MP for Nyali, and a former unsuccessful candidate for the Mombasa governor’s seat in the 2017 elections, argues that politicians fund criminal gangs during the election period to counter their rivals’ youth wings. ‘But thereafter the criminal gangs fund themselves by using any method to get money for their survival as most [of their members] are unemployed.’15

A wider spectrum: the political life of a gang

The use of gangs in election campaigns is a key part of their role in Kenyan politics. However, some gang members also work with politicians in other quid pro quo arrangements outside of the election period.

In the aftermath of elections, gangs may in some cases be hired to either suppress discontent over election results or to challenge them. Should their politician patron win office, gangs may also continue the work of intimidating and silencing rivals, targeting critical voices such as rival politicians, journalists or civil-society activists.

Politicians also come to mutually beneficial arrangements with gangs to wrest control of key resources and markets. This may be in the form of land grabbing or corrupt exploitation of municipal services. One key example of this is, perhaps surprisingly, waste collection. Gangs are widely involved in the waste sector in Kenya, from extorting residents in urban areas for waste-collection services to controlling dump sites. Gangs used in election campaigns may be rewarded with employment in the waste sector.

Cumulatively, the use of gangs by politicians can breed dysfunctional urban governance. Politicians contracting gangs – or in some cases, creating them – creates and sustains groups, which can then cause long-lasting damage to urban security. In turn, the gangs also sustain the type of political figures who will turn to violence and thuggery to maintain their power.

The failure to hold to account the individual politicians who engage in these practices is a problem, but understanding the role of gangs in specific politicians’ careers – as they have seemingly played a role in the career of Rashid Bedzimba – is one step towards accountability.

Notes

-

Telephone interview with a Mombasa-based journalist, 1 March 2020. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

This is a fund originally introduced in 2003 through an Act of Parliament. It was intended to be an independent source of development funds for MPs to meet the expectations of their constituents for grassroots development. It has since been challenged in court. Interview with a crime reporter, Mombasa, 14 February 2020. ↩

-

Interview with ‘Suleiman’, Mombasa, 4 December 2020. ↩

-

Interview with businessmen in a major trade association, 5 December 2019. ↩

-

Brian Otieno, Marwa slams Kisauni Wakali Kwanza gang, The Star, 16 July 2015, https://www.the-star.co.ke/counties/coast/2015-07-16-marwa-slams-kisauni-wakali-kwanza-gang/. ↩

-

Mohamed Ahmed, Kisauni MP Bedzimba denies financing Mombasa gangs, threatens to sue his accusers, Daily Nation, 4 May 2016, https://www.nation.co.ke/counties/mombasa/MP-deniesfinancing-Mombasa-gangs/1954178-3188488-format-xhtml-13q7f7pz/index.html. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Election Petition 2 of 2017, High Court of Kenya Mombasa, Rashid Juma Bedzimba (petitioner) vs Ali Menza Mbogo and others, http://kenyalaw.org/caselaw/cases/view/148408/. ↩

-

Interview, Mombasa, 11 February 2020. ↩

-

Interview, Mombasa, February 2020. ↩

-

Interview with ‘Salim’, Mombasa, 4 December 2019. ↩

-

Interview with Francis Auma, MUHURI programme officer in charge of rapid response, Mombasa, 4 December 2019. ↩

-

Interview, Mombasa, February 2020. ↩