Cannabis trafficking and endangered-tortoise trade drive corruption in Madagascar

The mountainous Andriry region near the town of Betroka in south-eastern Madagascar is an inhospitable area: remote, difficult to access and with a reputation for danger due to long-standing banditry and armed cattle-rustling groups. It is also one of Madagascar’s two main cannabis-producing regions, and home to organized groups of traffickers who control exports of the drug.

Hery (not his real name), the leader of one of these groups and a key cannabis supplier, described how his business works. He and his lieutenant reportedly control hundreds of young men in their trafficking organization,1 a claim backed up by a police officer who spoke anonymously and is tasked with a mission to arrest Hery and bring him to justice. This officer estimates that Hery has around 150 people in his gang.2

They control the cannabis shipments to exchange points on the outskirts of Betroka, from where transporters then take the shipments by road to drug bosses based in the capital, Antananarivo, and other towns, including Toliara, Antsirabe, Ihosy and Fianarantsoa.3

The Gendarmerie Nationale carry out an operation to destroy cannabis fields in Analabe, a district of Ambanja, in July 2020. More than a hundred hectares of cannabis were burned in the operation.

SOURCE: Gendarmerie Nationale, Ambanja, Madagascar.

A businessman and nightclub owner in Betroka explained how cannabis is brought from the mountain regions by transporters on foot, and left in clandestine drop-off places outside the city.4 Rehetse, an inmate in Betroka prison, who was arrested for acting as a cannabis transporter, described his own experience on this route. Working on behalf of a dealer based in Ihosy, he travelled with a group into the mountain region to collect a cannabis shipment. After paying his cut to Hery’s gang in order to move cannabis freely, his group were intercepted by police on their way back to Betroka. As the oldest member of the group, Rehetse was not able to flee in time.5

How Betroka became a major cannabis production hub has links to cattle rustling. One ex-politician, also a former cattle rustler, reported that many of the major players have, in recent years, switched their focus from cattle rustling to cannabis.6 Hery said that some in his gang were once cattle rustlers, but were now concentrating on drugs and looking to invest in artisanal mining. According to Hery, his gang recently reached a pact with regional law enforcement, whereby they would surrender any arms from cattle-rustling operations in return for being able to trade cannabis with impunity.7

The way Hery operates, and those like him, relies on complicity and protection. He reports that grands patrons ‘big bosses’ in Antananarivo ensure their protection and cover their activities.8 In Betroka, he claims that his group and their 30 or so subgroups pay annual fees to regional civil servants to ensure their collaboration.9 Other interviewees, from former politicians to public prosecutors, businessmen and police, also corroborated that corruption linked to the cannabis trade is widespread in the area.10

The World’s Rarest Reptiles

The south-west of Madagascar is the home range of the radiated tortoise, one of the world’s rarest reptile species. Along with the ploughshare tortoise – also native to Madagascar and even more endangered, as only a few hundred specimens are known to remain in the wild – radiated tortoises have in the past decade become highly sought after by reptile collectors in the international pet trade,11 as a forthcoming GI-TOC study explores.12

In the radiated tortoises’ home ranges, a large proportion of people depend on rural subsistence livelihoods. For centuries, tortoises have been part of the local diet as an important source of protein. Herilala Randriamahazo, a conservationist with the Turtle Survival Alliance, working on tortoise protection, told us that poaching for bushmeat remains a primary danger to tortoise populations.13

Theft of young radiated tortoises for international sale has grown significantly in the past decade. In 2018, two seizures of unprecedented scale – numbering over thousands of tortoises – were made in the island’s south-west.14 One of the experts interviewed believes that the buyer of the seized tortoises will be waiting for this order to be fulfilled, meaning that the pressure remains for thousands of more tortoises to be taken from the wild.15

Tortoise traffickers – predominantly Malagasy and Asian nationals resident in Antananarivo – use intermediaries who approach communities to conscript locals to poach live tortoises for a cash income.16 In this impoverished region, in which tortoises have traditionally been a food source to exploit, and not an endangered species to protect, this proves a strong incentive. The intermediaries then make payment on collection and arrange transport for the tortoises.

Different Markets, Similar Dynamics

The markets for cannabis and radiated tortoises may initially seem to be quite different: very different commodities, originating in different regions of Madagascar, and operating in very different social and political contexts.

However, in both cases, one of the challenges inherent in governing these markets is a lack of local-government legitimacy and a local acceptance of these trades. Conservationists try to integrate anti-poaching edicts into local law systems in a bid to encourage community compliance with national-level efforts to counter the tortoise trade.17 In the cannabis trade, Hery and his gang argued that producers and traffickers in the region are simply trying to find a source of income in a difficult environment, and that they saw cannabis as a legitimate way of making a living.

Both trades rely on the complicity of officials in source regions and along trafficking routes. Just like the multitude of officials on Hery’s gang’s payroll, officials in the south-west are encouraged to turn a blind eye to the tortoise trade, and trafficking intermediaries reportedly have strong links to law enforcement.18

Radiated tortoises seized in Maputo, January 2020. The distinctive radiated markings can be seen across their shells.

SOURCE: National Administration of Conservation Areas (ANAC), Mozambique.

Police inspection points along the main roads in Madagascar are widespread. Moving tortoises from the south-west to Antananarivo may entail passing up to 20 checkpoints. However, there are few reports of seizures at these checkpoints, implying that low-level corruption is common.19 The transport of large shipments of cannabis uses the same trunk roads leading to Antananarivo as those used for tortoise trafficking. These flows may be relying on the same modalities of corruption to move illegal goods, and their establishment along transport routes paves the way for multiple types of trafficking.

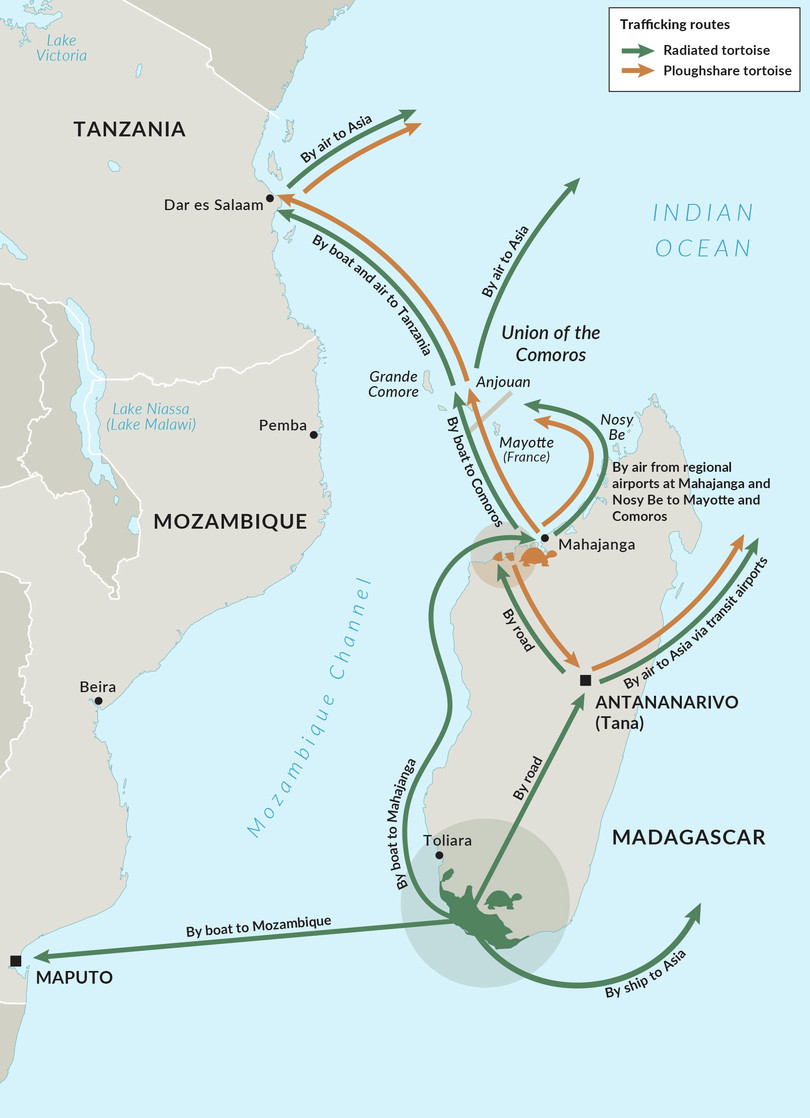

Shipments of tortoise and drugs other than cannabis also pass through many of the same transport hubs and regional destinations. Tortoises are transported overland to Antananarivo, and thence to Asian destination markets by air from Ivato airport. Alternatively, some traffickers ship radiated tortoises from the south-west by boat to Mahajanga for export to the Comoros islands.20 Similarly, international law-enforcement sources identified Mahajanga as a major hub port for drug shipments entering Madagascar,21 and previous Risk Bulletins have documented smuggling of migrants c.22

Secondary routes include regional flights from smaller airports to Comoros, Mayotte or Reunion. More recently, there have been reports of radiated tortoises going directly from south-west Madagascar on ships to China, or by fishing boat to Mozambique.23

Cannabis from Betroka is primarily shipped to Antananarivo and also services regional consumption markets across southern Madagascar. Cannabis from Madagascar’s other major production area, the northern Analabe Ambanja, is also shipped to Comoros via Nosy Be, an island off the north-west coast of Madagascar.24 Nosy Be is also an important hub for heroin shipments from Madagascar to other Indian Ocean island states, after heroin is brought into the country through other ports (particularly Toamasina) and consolidated, cut and repackaged in Antananarivo.25

Conclusion

Neither the illegal tortoise trade nor the cannabis market in Madagascar is a major priority for national or international law enforcement. However, our research into both shows similar dynamics of local corruption and acceptance of the illegal market at the community level. In the case of cannabis trafficking in Betroka, where our research has been centred, the reported corruption is significant and endemic. In illicit markets, corruption in source regions and along transport routes undermines the rule of law and also acts as a gateway for other forms of organized crime to operate through the same routes.

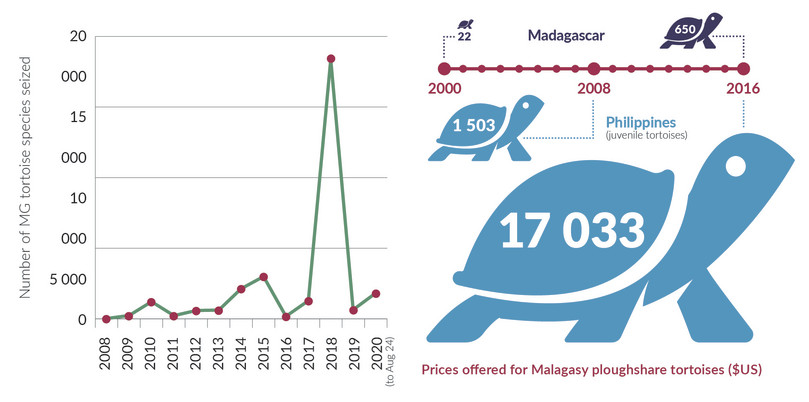

Figure 2 The graph on the left shows the trend in the number of trafficked tortoises seized globally. Two seizures involving thousands of radiated tortoises in 2018 were by far the largest on record. The timeline on the right shows the change in asking prices for ploughshare tortoises over time, both in Madagascar (the source country) and the Philippines (a market country). In both cases, there has been a marked price increase.

SOURCE: J Morgan et al, Ploughing towards extinction: An overview of the illegal international ploughshare tortoise trade, TRAFFIC (unpublished), thereafter compilation of media reports drawing on pricing surveys conducted by the authors over several years.

Figure 3 Major trafficking routes for ploughshare and radiated tortoises within and out of Madagascar.

SOURCE: GI-TOC fieldwork.

Figure 4 Major cannabis production areas and trafficking routes in Madagascar, both national and regional.

SOURCE: GI-TOC fieldwork.

Notes

-

Interview with Hery, leader of a cannabis trafficking organization, Betroka region, 3 July 2020. ↩

-

Interview with a police officer based in Betroka, 5 July 2020. ↩

-

Interview with Hery, leader of a cannabis trafficking organization, Betroka region, 3 July 2020. ↩

-

Interview with a businessman based in Betroka, 5 July 2020. ↩

-

Interview with an inmate of Betroka prison and former cannabis trafficker, 5 July 2020. ↩

-

Interview with ex-deputy mayor of Betroka, Betroka, 1 July 2020. ↩

-

Interview with Hery, leader of a cannabis trafficking organization, Betroka region, 3 July 2020. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with former politician in Betroka, 1 July 2020; interview with a guard at Betroka prison, 30 June 2020; interview with a police officer based in Betroka, 5 July 2020; interview with a businessman based in Betroka, 5 July 2020; interview with Ramarasota Jesse, public prosecutor in Betroka, Betroka, 2 July 2020. Jesse voiced suspicions of corruption among regional civil servants and politicians, but denied accusations of judicial corruption. ↩

-

Susan Lieberman et al, The ploughshare tortoise’s countdown to extinction, National Geographic, 20 September 2016, https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2016/09/26/the-ploughshare-tortoises-countdown-to-extinction/; John R Platt, Two years to ploughshare tortoise extinction?, Scientific American, 27 September 2016, https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/extinction-countdown/two-years-ploughshare-tortoise/; J Morgan et al, Ploughing towards extinction: An overview of the illegal international ploughshare tortoise trade, TRAFFIC (unpublished). ↩

-

Alastair Nelson, Exposing vulnerabilities in the Western Indian Ocean: The trafficking of Malagasy tortoises, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, forthcoming. ↩

-

Interview with Herilala Randriamahazo, Turtle Survival Alliance, Madagascar, Zoom call, 9 July 2020. ↩

-

Jani Actman, Stench leads to home crawling with stolen tortoises—10,000 of them, National Geographic, 20 April 2018, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2018/04/wildlife-watch-radiated-tortoises-poached-madagascar/; John C. Cannon, Thousands of radiated tortoises seized from traffickers in Madagascar, Mongabay, 31 October 2018, https://news.mongabay.com/2018/10/thousands-of-radiated-tortoises-seized-from-traffickers-in-madagascar/. ↩

-

Interview with a source in Madagascar, 9 July 2020. ↩

-

Alastair Nelson, Exposing vulnerabilities in the Western Indian Ocean: The trafficking of Malagasy tortoises, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, forthcoming. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with a source in Madagascar, 9 July 2020. ↩

-

Interview with Zo Maharavo Soloarivelo, National Coordinator, Alliance Voahary Gasy, via Zoom call, 3 July 2020. To overcome the cost of bribes along the road route, some traffickers will instead move radiated tortoises from the south-west by boat to Mahajanga for export to the Comoros. ↩

-

Ibid.; interview with Herilala Randriamahazo, Turtle Survival Alliance, Madagascar, Zoom call, 9 July 2020. ↩

-

Discussion with representatives of the US Drug Enforcement Agency working on drug trafficking in eastern Africa, 16 July 2020, via Zoom call. ↩

-

Civil Society Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa, Risk Bulletin of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa issue 9, June–July 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/esaobs-risk-bulletin-9/. ↩

-

Alastair Nelson, Exposing vulnerabilities in the Western Indian Ocean: The trafficking of Malagasy tortoises, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, forthcoming. ↩

-

Ongoing GI-TOC research into drug trafficking through the Indian Ocean island states, to be published in a forthcoming study. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩