Special report: Gangs in East and Southern Africa use lockdowns to target children for recruitment

Some impacts of coronavirus lockdowns have hit vulnerable children and their families hardest. On 15 March 2020, after the country confirmed its first case of coronavirus,1 the Kenyan government announced the closure of schools, which has since been extended to 2021.2 Schools in South Africa also closed earlier than scheduled on 15 March for the Easter break, before nationwide lockdown was imposed on 27 March. This has not only left children struggling for their education, but has also rendered some even more vulnerable to exploitation by gangs.

Kenya

Sources across Kenya report that they have seen a rise in child recruitment into gangs. Kevin Kola, a mentor at Greater Heights Initiative – a civil-society organization based in Nakuru, western Kenya, which is involved in the rehabilitation of gang members – reported that Confirm, one of Nakuru’s most notorious gangs, has been on a recruiting spree since the pandemic started.3

In Nairobi, Lucas Ogara, a Kilimani Officer Commanding Police Division, reported to People Daily that incidents of juvenile-gang attacks had increased since the pandemic hit Kenya, attributing this to a mixture of unemployment, insufficient parental supervision, impoverished living conditions and poor education.4 Meanwhile, Nairobi Regional Police boss Philip Ndolo confirmed that crime involving primary-school and secondary-school students was on the rise.5

Civil-society leaders in Mombasa who are working on these issues said that many teenagers are joining gangs such as Wakali Kwanza, Wajukuu wa Bibi and Team Popular, some of the most notorious in the city.6

Starting small

Nairobi’s Kibera slum under lockdown in July 2020.

© Thomas Mukoya/Reuters

A man shows scars from gunshot wounds sustained when he was attacked by a gang in Makadera in Nairobi, 27 April 2015.

© Reuters/Siegfried Modola

In an interview, Onyango (not his real name), a Confirm leader in Nakuru, described the gang’s recruitment process:

Casual interaction is one of the first steps we are taking. It helps us gauge the smart ones who can keep secrets. We then have them hang around us at the base basically to get attracted to the lifestyle by seeing how our members live. They run small errands like purchasing airtime or snacks as a dry run. After a few weeks of random rewards for these errands, they are then tasked with sending messages and reporting the numbers that go through, a key strategy in our online money heist.

Confirm are known for specializing in phone-based scams, namely so-called virtual kidnappings. In these, gang members use information drawn from platforms such as social media to threaten their victims, either claiming that they have a family member hostage, or that the family member needs money for urgent medical care. Once cash is transferred, they switch off the phone. The early steps of these scams are simple and monotonous tasks, and to perform them Confirm recruit children. As Kevin Kola explains:

As long as you can count and write numbers, you are eligible for recruitment. Many of the children who are picked are tasked with sending fake M-PESA [the Kenyan mobile-money system] messages, claiming that the recipient has won a certain amount of cash. Whereas this is based purely on guesswork, the kids note down which numbers went through and forward them to older gang members, who then make calls to the unsuspecting victims. For KSh 600 (US$6) a day, the children often view this as a harmless task.

Confirm are unique among Kenyan gangs for their specialization in technology-based crimes. Elsewhere in the country, children perform various other roles for gangs. Hip-hop artist Ohms Law Montana, who is also the Founder of Acha Gun Shika Mic (drop guns and hold mics), a movement that seeks to reform gangs in Mombasa, suggests that gang members have been approaching children for recruitment as, being younger, they are easier to manipulate: ‘The corona period has confirmed that children are more malleable than adults, it is easy to bend their will and get them to do what you want.’7

Montana reports that, in Mombasa, some children act as lookouts during robberies, while others are used for getting into small spaces. During break-ins, these children climb into windows and pass stolen items to awaiting gang members. He added that the kids are taught some skills, including how to attack people and steal from them, and are deployed on missions. The availability of weapons, which are offered to the kids upon learning their new trade, including knives and machetes, has also been on the rise.

Closed schools aid recruitment efforts

School closures have been a major factor in children becoming more vulnerable to recruitment by gangs. In the absence of the structure, supervision and sense of inclusion that schools offer, disadvantaged children may find gang life increasingly appealing. Kola says that, in Nakuru, the few recruits who worked part-time are now working full-time, as there is no school to keep them occupied.

Montana and Kola argue that the sense of belonging and need for money are key factors leading to the pull of gangs for children. ‘More and more children are now giving in due to peer pressure, both in their immediate surroundings and on social media, and the desire to upgrade their lifestyle,’ said Kola.

Three recent Confirm recruits described how they benefit from being part of a gang. Brian, 14 (the names of the recruits have been changed),8 keeps an eye on law-enforcement officers: ‘I ride bikes around the neighbourhood and spy around. No one suspects anything because children ride bikes all the time. I give reports of police operations for a KSh 100 [US$1] tip.’

Stephen, 15, started out by forwarding messages: ‘My brother is a member of the gang and he always has money. I inquired from him if I could join too. He taught me how to send the messages and how to get the money. I used to do it at night but one time I went in during the day and I have been doing it [ever] since as my full-time job.’9

Cyrus, 16, uses crime to fend for himself: ‘I’m very proud of my accomplishments. My father and I are not in good terms and he calls me “useless” a lot. He does not provide for me at all, so I use crime to become self-sufficient. I hope one day I can make enough to furnish my single room and save up to invest in a mitumba [second-hand clothes and shoes] business. I don’t want to do this forever.’10

The travel bans and business lockdowns have left many families in poor areas of Kenya’s cities struggling to make ends meet. In Kibera, a slum area of Nairobi, several gang members reported that they were distributing food among the community, and specifically targeting children of primary- and secondary-school age. They pointed out that this immediately attracts children to the gangs, since ensuring regular meals has been a struggle in recent months.

‘They even followed us, asking to help them learn the trade. Most are barely 13 but they feel the need to substantiate their parents’ income. So far, we have more than 20 new dedicated recruits and they are keen to join us in minor crimes like pickpocketing and snatching phones while on a motorbike,’ said one gang member. He said that the gang was also providing basic necessities, including water, a scarce commodity in the slums. ‘We even have handwashing bays where we meet and interact with many young people on a day-to-day basis. In this exchange, some of them have shown interest in our flashy lifestyle and also keep asking where we get cash for the phones we use. This is the opportune time to talk to them about the benefits of being one of us.’

South Africa

As in Kenya, children have long been exploited by gangs on the Cape Flats. Referred to locally as ‘springbokkies’ – in reference to South Africa’s symbolic antelope – child recruits are used by gangs to keep a lookout for the police, carry guns to shooters, or deliver drugs and other illicit goods.11 Sometimes, more than three children positioned in different streets pass a gun to one another, so that the gun reaches the shooter and is moved out of the vicinity before police arrive. The children then hide the gun in their homes.12

Children are also used as shooters themselves, using their seeming innocence as an advantage, while some children are recruited simply to be sacrificed. When two gangs in conflict are required to ‘pay back in blood’ to settle a score, they may send a child as a sacrifice. The child is given a gun and told to shoot a member of the rival gang; yet the gun given to the child is faulty and the rival gang is prepared for the child’s arrival. They do not know they are being set up until it is too late.

Gangs in South Africa have long exploited the fact that children below the age of 10 do not have criminal capacity in law13 and therefore cannot be arrested for an offence.14 People under the age of 18 are also considered minors and cannot be tried as adults. Recruiting children essentially lowers the gangs’ risk of attracting attention from law enforcement.

Yet children have always been – and continue to be – drawn to the gangs’ aura of power and money. Jamiel, a 36-year-old member of the Americans gang, described how he was recruited at a young age:

I was … just really a junior when I joined the gangs at school. I didn’t really know anything other than the fact that I wanted to be an American gang member. They all had guns and plus they had cool teeth, and all the best clothing and the best shoes, some of them had the newest Ford with the spoilers and the cool rims and I knew that when I became an American then I would be able to also get those things. So, when I started, I was maybe nine years old and they gave me a knife and I poked [stabbed] this other kid at school that was always looking for kak [looking to cause trouble] with me … from then, nobody messed with me. They gave me a gun when I was 12 years old and I shot some people.

Jamiel said that, despite the killing and the prison time he has served since, he has no regrets about his choice of path, because people in the community respect and fear him.15

Ivan Daniels, a former member of the Hard Livings gang, now a pastor in Manenberg, Cape Town, describes how Jamiel’s story is not unique:

These gangsters have very young shooters, some as young as 10 years old. … I’ve seen an eight-year-old carry a knife and a gun. Because these areas are so destitute with poverty and unemployment, these kids only see the gangsters and the gang bosses as a possible career choice … their own families don’t have money and they live from hand-to-mouth, whereas the gangsters always have money and new clothes and jewellery … and the gang boss is driving a new car every six months, and so it becomes a very attractive prospect for these children.16

Gangs have a sophisticated system of recruitment, involving recruiting children to sell drugs at schools to form junior school-age gangs. Those youngsters who show potential through their capacity for violence may then be brought into the main gang.17 Recruiting children provides the gangs with a stream of malleable young members willing to prove themselves.

Spuikers (not his real name)18 was born into a family of violence and gangsterism in Manenberg, a gang-ridden and poverty-stricken community in Cape Town. His grandfather and father were senior gang leaders. At the age of eight, Spuikers committed his first murder. He was taken to Manenberg Police Station, where police officers arranged for a social worker to provide him with counselling.

At the age of 11, he bragged about how being a member of the Clever Kids gang provided him with money, drugs and women. At 13, while trying to kill a rival gang member, he killed a three-year-old boy in the crossfire. He was taken into custody, then, after being released on bail, shot the rival gang member he had initially failed to kill.

Now, at the age of 15, Spuikers has already committed four murders. On 28 October 2020, he will appear at the Child Justice Court where it will be argued if his sentence should include imprisonment. His story, like Jamiel’s, demonstrates how children can be drawn from an incredibly young age into the gang ecosystem.

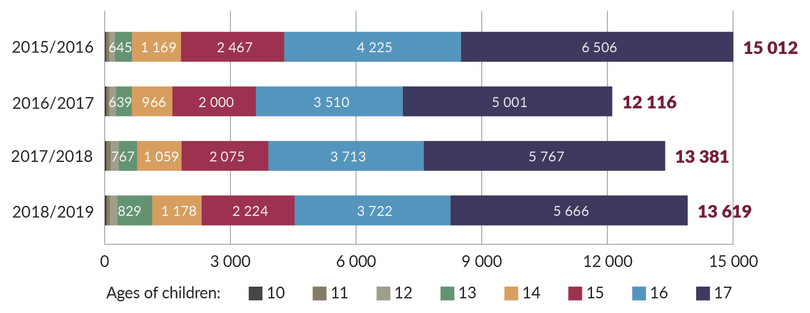

Figure 1 Total number of children in conflict with the law, South Africa, 2015–2019 by financial year.

SOURCE: Integrated Case Management System: Child Justice.

Murders committed by children on the rise

Monitoring of South Africa’s crime trends suggests that child recruitment has been on the rise for some time. The number of children appearing in Child Justice Courts has increased in recent years,19 and in 2018–2019, 33 per cent of all criminal activity involving minors across South Africa took place in the Western Cape, home to the gang-ridden Cape Flats.20 Murders committed by children also rose sharply between April 2019 and March 2020, along with an increase in the number of child victims of crime. Observers have argued that murders committed by children in the Western Cape are largely attributable to gangs, a phenomenon that contributes ‘significantly to violence committed by children’.21

This trend has accelerated under lockdown. The GI-TOC commissioned a series of 42 interviews with former and current gang members across the Cape Flats during the first three months following the beginning of lockdown on 27 March 2020. Recruitment trends changed over the period: at the start of lockdown, when restrictions on movement were severe and police presence in the streets was high, gang members reported that recruitment fell as the contexts in which they would interact with vulnerable children were restricted. As lockdown continued and restrictions were gradually relaxed, responses reported that recruitment was rising, particularly of school-age children who were not attending school.

Targeting the most vulnerable

Interviews with members of Cape Flats communities and activists working against gang violence showed the same drivers at work in South Africa as those observed in Kenya.

School closures have left already vulnerable children even more vulnerable. As in Kenya, the absence of school leaves some children bored, in need of money and lacking a sense of belonging. In the words of one Mr Jenkins, a resident of Mitchells Plain, Cape Town, ‘With all the children being home now, I worry a lot because even the good children that used to go to school are now roaming the streets here with nothing to do [and] that is when the gangs jump on them and lure them into joining.’22

In these communities, school does not only offer an education: many of the schools on the Cape Flats also run feeding schemes and after-school activity programmes aimed at keeping children away from gangsterism – support structures that are impossible in lockdown. Many children would also take food home to share with their families, who now face hunger. This has brought about an increase in the number of parents and guardians grooming their children to work for gangs in return for food and money.23

Manenberg residents march against a spike in gang violence as part of the Taking Back Our Streets Campaign, Manenberg, Cape Town.

© Shaun Swingler

Members of the Young Gifted Bastards gang smoke a bottleneck pipe in Blikkiesdorp, Cape Town.

© Shaun Swingler

Roegchanda Pascoe, an anti-gang activist from Manenberg, said that ‘families desperate for food are told by gangs that the police or army will not interrogate children, so all the child needs to do is deliver drugs to a buyer two blocks away. We see gangsters getting away with this because there are often images of army presence in the Cape Flats with one or two children in the background. Those children are being used by the gangs.’24

Our ongoing research into the impact of the lockdown on gangs in Cape Town has found that they have become more economically and socially powerful. Employers’ businesses have closed down, communities have become more desperate and families have lost income. But, at the same time, illicit economies have continued, placing gangs in a better position. Civil society groups in Colombia have similarly warned that recruitment of children by armed and criminal groups there has accelerated under lockdown, for similar reasons.25

Reggie Jacobs, a pastor and community leader in Mitchells Plain, described how the increased power of gangs in lockdown is drawing in ever more young recruits:

When people were complaining that there’s no jobs [because of the lockdown], it was the gangs who still had their same identity … the gangs also had money, drugs, alcohol, guns and power. … They will know exactly how attractive they are to the youth, because they manipulate that power that they have like a spider luring an insect into its web. … Now the children are also not going to school and they are therefore ripe pickings for the gang boss.26

Although these main drivers have been accentuated during lockdown, when children are able to return to school in these settings, the hardship and hunger drawing young children to gangs will remain.

Notes

-

KTN News Kenya, Breaking news: All schools to be closed indefinitely, 15 March 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TMoA2L8p1mw. ↩

-

BBC News, Coronavirus: Kenyan schools to remain closed until 2021, 7 July 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-53325741. ↩

-

Interview with Kevin Kola, mentor at Greater Heights Initiative, Nakuru, by phone, 7 August 2020. ↩

-

Zadock Angira and Roy Lumbe, Concern over rising teenage face of crime, People Daily, 15 May 2020, https://www.pd.co.ke/news/national/concern-over-rising-teenage-face-of-crime-36671/. ↩

-

Amina Wako, Number of students in crime on the rise in city – police, Nairobi News, 20 June 2020, https://nairobinews.nation.co.ke/editors-picks/number-of-students-in-crime-on-the-rise-in-city-police. ↩

-

Interview with a civil-society activist in Mombasa, August 2020. ↩

-

Interview with Ohms Law Montana, founder, Acha Gun Shika Mic, by phone, 12 August 2020. See also Amina Wako, Number of students in crime on the rise in city – police, Nairobi News, 20 June 2020, https://nairobinews.nation.co.ke/editors-picks/number-of-students-in-crime-on-the-rise-in-city-police. ↩

-

Interview in Kivumbini, Nakuru, 8 August 2020. ↩

-

Interview in Kanyon, Nakuru, 8 August 2020. ↩

-

Interview in Kwa Rhonda, Nakuru, 8 August 2020. ↩

-

Rukshana Parker and Michael McLaggan, Cape gangs in lockdown: Saints or sinners in the shadow of COVID-19?, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 22 April 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/gangs-in-lockdown-manenberg/. ↩

-

Warda Meyer, The kids who have to join a gang or die’, IOL, 22 September 2014, https://www.iol.co.za/news/the-kids-who-have-to-join-a-gang-or-die-1754378. ↩

-

Section 1 of the Child Justice Act, Act 75 of 2008. ↩

-

In June 2020, the Child Justice Amendment Bill was passed. The Bill increased the minimum age of criminal capacity of children who have committed an offence from 10 to 12 years old. The new age of criminal capacity means that children up to 12 years old lack criminal capacity and cannot be arrested for committing an offence. Although this brings South African legislation in line with international standards, which acknowledge that children under the age of 12 in conflict with the law are most likely to be at risk and in need of intervention, gangs will certainly use loophole this to their advantage. Although the Amendment Bill has been signed into law, the amendment only becomes effective on a date yet to be stipulated by the president. Until then, the age limit remains at 10. ↩

-

Interview with Mr Jamiel ‘Killah’ Hendricks, 36-year-old Americans leader, Heideveld, Cape Town, 20 June 2020. ↩

-

Interview with Ivan Daniels, Manenberg, Cape Town, 28 May 2020. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Spuikers is known to an anti-gang activist working with the GI-TOC. ↩

-

2017-18 Inter-departmental Annual Reports on the Implementation of the Child Justice Act, 75 of 2008 at p 25. ↩

-

2018-19 Inter-departmental Annual Reports on the Implementation of the Child Justice Act, 75 of 2008 at p 33–34. ↩

-

Sameer Naik, Children responsible for 779 murders in 2019/20, IOL, 31 July 2020, https://www.iol.co.za/Saturday-star/news/children-responsible-for-779-murders-in-201920—d658ee2b-d17d-430b-9465-81300b6d62a0. ↩

-

Interview with Mr Jenkins, Cape Town, 2 May 2020. ↩

-

Interview with Roegchanda Pascoe, Cape Town, 18 August 2020. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Lara Loaiza, How Colombia’s Lockdown Created Ideal Conditions for Child Recruitment, InSight Crime, 28 August 2020, https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/colombia-lockdown-child-recruitment/. ↩

-

Interview with Reggie Jacobs, Westridge, Mitchells Plain, 27 June 2020. ↩