Kenya’s ill-regulated mass transit industry provides a convenient way of ‘cleaning’ dirty money – and it appears various corrupt interests would like to keep it that way.

The arrest in October 2019 of Rose Musanda Monyani, owner of five passenger buses (known in Kenya as matatus), and her appearance in court in Nairobi on narcotics charges and related money laundering,1 have exposed a major avenue being used to cleanse proceeds of crime in Kenya. During investigations, police recovered KSh25 million in cash (equivalent to US$250 000) and an ‘unknown substance’ that contained 40% heroin in her house in Kinoo, Nairobi. Officials from the Assets Recovery Agency claim Monyani has not been able to provide a reasonable explanation for the source of her wealth.

In the past, in Kenya, proceeds of crime have been laundered mainly through real estate, betting companies, nightclubs, religious outfits, hawalar (an informal money- exchange system) and political campaigns. However, matatus – vans and minibuses that offer affordable public passenger transport for millions of travellers, especially commuters – have not been a focus for investigators. The reason for this omission lies in the highly informal nature of the sector, and the presence in the industry of politically influential figures who resist attempts to regulate it.

While the Kenyan media has identified links between the matatu industry and money laundering for some years, highlighting the cash-based nature and weak regulation of the sector as its key vulnerabilities,2 authorities have not previously taken action. According to one official in the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) in Nairobi, ‘We have all along suspected that matatus are central in money laundering, but we have had no clear case to work on in the past. We stumbled on this one [the Monyani case] by coincidence. It was the first case of its kind, and now our antennae are up. I think this is a big story building up: the matatu business is huge in this country and criminals could be taking advantage of its informal nature to launder large sums of money.’3

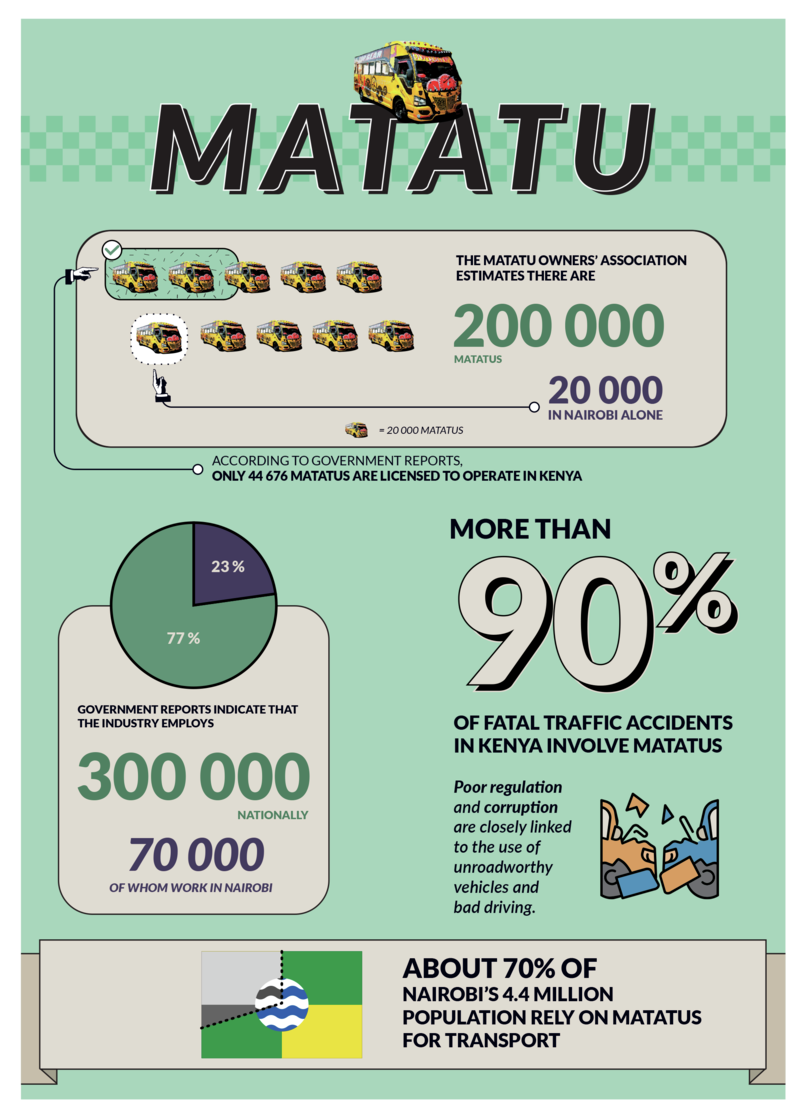

The matatu sector is central to Kenya’s economic well- being. Although reliable estimates of the value of the sector are unavailable due to its informal nature, government reports indicate that hundreds of thousands are employed in the industry: from drivers and conductors to callers (those who entice passengers to board vehicles) and operators (matatu owners). As Figure 6 shows, matatus provide the main means by which Kenya’s urban population travel, and are a key source of mobility in large cities, such as Nairobi, which have not been planned with pedestrians in mind.4 The matatu industry is both a major employer in its own right and a facilitator of Kenya’s urban economy.

However, at the same time, there are a range of other informal beneficiaries who exploit the profits generated by the matatu sector and who, in the final analysis, terrorize the business by increasing costs while discouraging fair competition. These include corrupt traffic police and judicial officers, criminal gangs who control matatu terminals and extort the business, gangs who control particular matatu routes, as well as criminal and political figures embedded in the industry. An investigation by the Daily Nation newspaper estimated that the industry loses, on average, KSh47 billion annually to this kind of extortion (equivalent to around US$470 million).5

Money-laundering channels in the matatu industry

From our interviews with representatives of the DCI in Nairobi, there are four main routes through which money is laundered into the matatu sector:6

First, some drug-trafficking figures started off as matatu drivers, and then seized the opportunity to develop drug-trafficking networks, by bringing their passengers, other players in the sector and corrupt police officers into their networks. They then expand their networks to draw in influential people, including politicians by funding their elections campaigns. They turn back to matatus as their key avenue for laundering their proceeds once they become established in the drugs market. Other avenues include real estate, haulage transport, and clearing and forwarding companies.

Secondly, criminal actors who have made their money elsewhere seize the opportunity offered by the lack of regulation to invest in the matatu industry. The vulnerability of the industry is obvious to those outside due to its chaotic nature, the lack of regulatory control over routes and fares, the sheer number of protection rackets that operate in the industry, and its reliance on cash payments.

Thirdly, corrupt police officers, especially traffic police, recycle money extorted from matatu businesses back into the industry, either personally or through proxies. A proportion of matatus in Kenya are owned or part-owned by police officers, creating a clear conflict of interest. President Uhuru Kenyatta issued a decree earlier this year compelling traffic police to choose either law enforcement or the matatu business.7 This is the latest move after government bodies have, for several years, highlighted the issues inherent in police involvement in the sector and the harassment by police of matatu businesses in competition with their own business interests.8

Finally, gang members and matatu cartels – terminal- controlling gangs, route controllers and protectors – extort from small-time matatu operators, venture into the highly paying but risky narcotics businesses, and then invest the proceeds back into the matatu sector.

Why the matatu industry is vulnerable to exploitation

As shown by the number of routes through which illicit funds are channelled through the matatu industry, it is proving to be a magnet for criminal actors and money launderers, particularly those connected to narcotics. There are several key reasons for this. Firstly, the industry is subject to very little regulation: the National Transport and Safety Authority (NTSA) – the state agency charged with overseeing and regulating the sector – is even uncertain about the total number of matatus on the Kenyan roads. Depending on the source, figures vary from slightly above 45 000 to a million.9 The entry requirements for potential investors are also low: the only requisite is that a vehicle meets certain minimum standards10 and that the owner has a public service vehicle licence.

Criminal interests in the sector undermine regulatory institutions in various ways. Extortion in its various forms has led to fare increases. The involvement of police officers – either as operators or protectors – has encouraged law breaking in the industry. The Matatu Owners’ Association claims that cartels eat away at their profits: ‘We are left with the major expenses, such as insurance and repairs, while the bulk of the harvest is scattered across the extortion ring,’ said MOA chairperson Simon Kimutai in January 2017.11

Figure 6 Kenya’s matatu industry unpacked

Powerful vested interests also push back against efforts to regulate the matatu sector more stringently. The most influential operators (i.e. politicians, law-enforcement officers and wealthy businesspeople) are able to allocate themselves the most profitable routes at the expense of regular matatu owners, and against the wishes of the NTSA. Every move to regulate the sector would appear to be for self-gain, to either benefit powerful bureaucrats and politicians or aid wealthy matatu owners to crowd out weak ones. For example, an attempt by the authorities in 2014 to introduce a cashless payment system for matatu users, which would have increased accountability and transparency in the industry, was unsuccessful.12 As noted at the time by prominent Kenyan economist David Ndii, the system was resisted by those who had ‘vested interests in a cash business, notably the money-laundering syndicates and the police extortion cartel’.13

There seems to be a recurring cycle, whereby corruption, political influence and criminality weaken regulatory control of this vital industry, which, in turn, makes it a more attractive money-laundering opportunity for other criminal actors.

Notes

-

Abiud Ochieng, Suspected drug leader used matatu business to launder money, Daily Nation, 22 October 2019. ↩

-

David Ndii, Who is afraid of commuter ride-hailing apps? Tech meets matatu, and why Nairobi does not need state-run public transport, The Elephant, 17 October 2019, https://www.theelephant.info/op-eds/2019/10/17/who-is-afraid-of-commuter-ride-hailing-apps-tech-meets-matatu-and-why-nairobi-does-not-need-state-run-public-transport/; Peter Polle, The good and the bad of matatu industry in Kenya, 23 June 2017, www.talwork.net.. ↩

-

Interview, Nairobi, 12 November 2019. ↩

-

Commentators and historians have described how, under colonial rule, the layout of Nairobi and other urban centres was shaped around the needs of a car-owning elite, to the detriment of the rest of the population – and to the ongoing detriment of pedestrians today. See Rasna Warah, Nairobi: A city in which ‘contempt for the resident is everywhere apparent’, The Elephant, 12 July 2018, https://www.theelephant.info/features/2018/07/12/nairobi-a-city-in-which-contempt-for-the-resident-is-everywhere-apparent/; Patrick Gathara, The walking poor: Nairobi privileges the motor vehicle, not the people, The Elephant, 16 November 2018, https://www.theelephant.info/features/2018/11/16/the-walking-poor-nairobi-privileges-the-motor-vehicle-not-the-people/. ↩

-

Edwin Okoth, How city cartels rake in billions from matatu owners with police help, Daily Nation, 5 January 2017, https://www.nation.co.ke/news/-Inside-the-Sh47bn-criminal-network-that-runs-matatus/1056-3506950-q5pyp0/index.html. ↩

-

Interview with official from the Directorate of Criminal Investigations, Nairobi, 12 November 2019. ↩

-

Michael Ollinga Oruko, Uhuru tells police officers to choose between doing private business and serving public, Tuko News, January 2019, https://www.tuko.co.ke/297032-uhuru-tells-police-officers-choose-private-matatu-businesses-serving-public.html. ↩

-

Wangui Maina, Task force wants police barred from owning matatus, Business Daily, 14 January 2010, https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/corporate/539550-842368-5i8s4uz/index.html; Fred Mukinda, Traffic officers ordered to quit matatu business or face sack, Nairobi News, 25 February 2016, https://nairobinews.nation.co.ke/newstraffic-officers-ordered-quit-matatu-business-face-sack. ↩

-

See, for example, International Labour Organization; ILO Growth Nexus III Project (matatu sector in Kenya), 2016; and Graham Kajilwa, Why the public has to wait until 2024 for safer matatus’, The Standard, 23 January 2018, https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/elections2017/article/2001266944/state-dithers-on-safety-standards. ↩

-

These concern the vehicle’s size, configuration and age. ↩

-

Edwin Okoth, How city cartels rake in billions from matatu owners with police help, Daily Nation, 5 January 2017, https://www.nation.co.ke/news/-Inside-the-Sh47bn-criminal-network-that-runs-matatus/1056-3506950-q5pyp0/index.html. ↩

-

Joshua Masinde, Nairobi’s colorful but chaotic local bus system is resisting being digitized, QZ, 8 November 2018, https://qz.com/africa/830442/nairobis-matatu-bus-system-has-resisted-being-digitized-for-more-convenient-transit/. ↩

-

David Ndii, Who is afraid of commuter ride-hailing apps? Tech meets matatu, and why Nairobi does not need state-run public transport, The Elephant, 17 October 2019, https://www.theelephant.info/op-eds/2019/10/17/who-is-afraid-of-commuter-ride-hailing-apps-tech-meets-matatu-and-why-nairobi-does-not-need-state-run-public-transport/. ↩